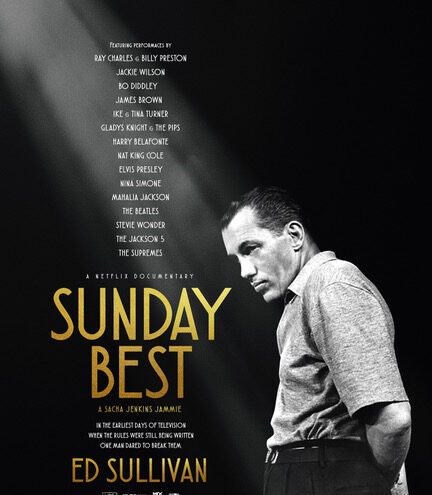

Sunday Best, a new documentary from director Sacha Jenkins just premiered exclusively on Netflix, July 21st.

Sunday Best uncovers the untold story of The Ed Sullivan Show’s legacy in amplifying Black music and culture.

While many remember host Ed for introducing America to Elvis and The Beatles, his commitment to showcasing Black talent was just as bold, and arguably more impactful. During a time when segregation was still legal, and mainstream media often excluded Black voices, Ed Sullivan consistently featured Black musicians, comedians, sports figures, and change makers.

This documentary Explores Sullivan’s powerful mark on music, media, and The Civil Rights Movement. Sunday Best, includes never before seen interviews from Harry Belafonte, Dionne Warwick, Berry Gordy, Otis Williams and many more.

Sunday Best does remind us that integration didn’t just happen in courtrooms or lunch counters, but on living room TVs across the country.

I’ve been writing about the musical and socio-political impact of Ed Sullivan for many decades. My next book Screen Gems: Pop Music Documentaries & Rock and Roll TV Scenes, due in 2025, devotes an entire chapter to his monumental cultural celluloid achievements.

Ed Sullivan was my Sunday School teacher.

The Ed Sullivan Show spotlighted history-making music performances by Elvis Presley, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Animals, the Doors, Diana Ross & the Supremes, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Marvin Gaye, the Turtles, Neil Diamond, Smokey Robinson & the Miracles, the Beach Boys, and the Jackson 5, for example.

In a time of racial segregation, Sullivan was an influential advocate of civil rights. He invited African-American actors (Pearl Bailey, Dorothy Dandridge, Diahann Carroll), athletes (Muhammad Ali, Jackie Robinson), comedians (Godfrey Cambridge, Richard Pryor, Flip Wilson), and musicians (Harry Belafonte, James Brown, and Motown artists such as the Four Tops, the Temptations, and the Supremes), to name just a sampling.

Along with millions of other teens, I felt the emotional and sonic impact of the Beatles’ Sullivan debut. Two other Sullivan guests transformative for me were Little Anthony & the Imperials on March 28, 1965, with Anthony’s mesmerizing lead vocal on “Hurt So Bad,” and soul singer/dancer James Brown singing a medley of his hits on May 1, 1966.

Inexplicably, Ed Sullivan is not in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The Ed Sullivan Show (1948), broadcast live Sundays at 8 p.m. on the CBS television network from 1948 to 1971,charmed prime-time TV viewers for the last time when it wrapped its final episode on June 6, 1971.

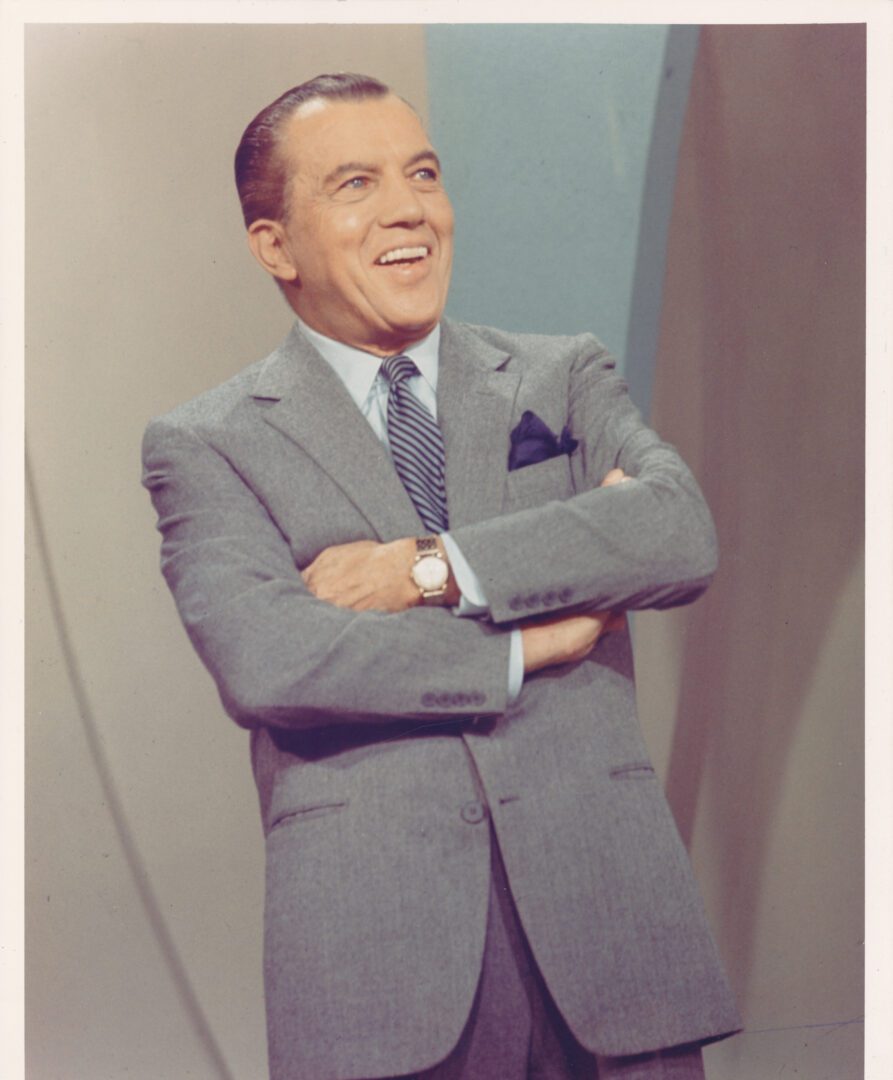

Host Ed Sullivan, a celebrated 1940s New York sports and entertainment newspaper reporter and columnist, became a pioneering TV broadcaster who presented a stunning variety of entertainers and pop culture figures in the show’s twenty-three-year run: singers, musical performers, comedians, film stars, sports figures, jugglers, tumblers, plate spinners, and emerging talent of all kinds.

Longtime director John Moffitt helmed nearly 1,000 hour-long episodes. The Sullivan library houses 1,000 hours and more than 10,000 performances in black and white and color (the first show broadcast in color was on October 31, 1965, in the eighteenth season).

Broadcast in front of a studio audience mostly in CBS’s Studio 50 (renamed “the Ed Sullivan Theater” in 1967) at 1697-1699 Broadway in Manhattan, between West 53rd and West 54th Streets, and sometimes originating from CBS Television City in Hollywood, The Ed Sullivan Show was a weekly snapshot of what was happening at that moment. The shows and guests were often topics of conversation on Monday mornings at work or school.

From the outset, when television was in its infancy, Sullivan was personally involved in his show’s bookings and known to have said he wanted to “entertain all of the people some of the time”—from providing grandparents with glimpses of vaudeville, to offering parents top-tier Hollywood personalities and athletes, to bringing teenagers their next poster idols, and youngsters the Italian mouse, Topo Gigio. Sullivan cast aside racial, political, and cultural boundaries to ensure his audiences witnessed the best and the brightest talent.

For them, and indeed, for artists of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, a performance on The Ed Sullivan Show represented a pivotal career milestone, bringing their talents to mainstream America and catapulting them to the top of the charts with breakout success.

The library remained in the Sullivan family’s possession for almost two decades after The Ed Sullivan Show wrapped. In 1990, documentary filmmaker-producer Andrew Solt formed SOFA Entertainment Inc. and acquired the library from Sullivan’s daughter and son-in-law for an undisclosed sum. The Los Angeles-based production company became the copyright holder of the original programs and, eventually, more than 150 hours of newly created programming.

Solt is one of those American kids who grew up watching Sullivan on Sunday nights. Along with his aforementioned theatrical documentaries, his filmography includes the longform TV special Heroes of Rock ’n’ Roll (1979), an early collaboration with Malcolm Leo; and the miniseries The History of Rock ’n’ Roll (1995). SOFA Entertainment has produced approximately 400 programs for television and home video, including Elvis: The Ed Sullivan Shows (2006).

In 2023, UMe inked a deal with Solt and SOFA and secured the global digital rights to The Ed Sullivan Show. The terms were not disclosed. That officially brought complete shows and special guest segments to streaming platforms worldwide for the first time via the show’s official YouTube channel and website at edsullivan.com.

UMe upgraded many of the individual performances to high-resolution clips as part of the agreement. With five years of digital content experience at Google, Josh Solt, SOFA Entertainment’s president, has been overseeing the production.

“Sullivan knew how to give a show that was for every generation that might be watching,” Andrew Solt explained during a September 2011 interview.

“The show was such a launching pad for such great, important, iconic moments, whether it’s Elvis or Bo Diddley. When the Beatles stepped onto Ed Sullivan’s New York stage on Sunday, February 9, 1964, to make their American TV debut, 86 percent of all TVs on at that hour—73 million Americans—were tuned in. It was the most-watched program in history to that point and remains one of the most-watched programs of all time. To some, it will always be remembered by his introduction: ‘Here they are—the Beatles!’”

“The relationship between Berry Gordy’s Motown label and The Ed Sullivan Show also made music and television history,” Solt noted.

“Soon after the Supremes’ debut on Sullivan (December 1964), it was clear that showcasing the latest Motown releases on CBS on Sunday nights (thirty-five million viewers was average) until 1971 was a way to expose the record company’s newest hits and boost the show’s ratings.”

Solt and I discussed Sullivan’s influence on the world of African-American entertainment.

“Ed had a fascination with African-American culture. He loved talent. He stood up for Harry Belafonte and Marian Anderson. Mahalia Jackson sang on the show, and one of the very first shows W.C. Handy sang was on The Ed Sullivan Show. He is considered the father of the blues.

“For one, a Harlem DJ, Dr. Jive, introduced R&B artists to America in late 1955. “Rock Around the Clock” was blasting out of every transistor radio and the main titles of Blackboard Jungle. Ed loved introducing African Americans on his stage, and most of all he enjoyed giving people big breaks and the most desired gift, national TV airtime. Ed liked his role as showbiz kingpin, and he knew he was very fortunate to be such a powerful arbiter of American taste. He took pleasure in influencing our culture and [presenting] acts that would make us gasp and swoon.

“He was an unlikely hero.”

“For us, being on The Ed Sullivan Show was so much more than record sales,” Mary Wilson of the Supremes emphasized when I interviewed her in 2016.

“It wasn’t about promoting us. It was about that we had grown up watching The Ed Sullivan Show. We had grown up watching shows where you didn’t see a lot of Black people starring on those shows. We were like every other family in America who spent hours watching Ed Sullivan. So, for us, being on the show was such a great honor, because we were there to see the world changing. To see America changing. We were excited! We’re on The Ed Sullivan Show.

“We came from a time when a whole family of all different colors didn’t sit around watching Black people on television. The Dick Clark Caravan of Stars tours were before us and there were segregated hotels.

“For us, that is what it was all about. We were part of that change. We were part of helping America to see Black people, Black women, being proud, beautiful, and successful. It wasn’t just us. Many people before us. But they didn’t have the television to expose them to that wide range of people as we did. We were lucky. We stood on a lot of shoulders. But we were there when the doors opened.

“The other thing was that we were seen in color after our initial appearances were in black and white. Recently, my granddaughter was watching a DVD collection of the Supremes. And she said to me, ‘Grandma! What happened to the color?’ Because she has never seen a black and white TV!”

The Temptations were among the most popular and influential Motown vocal groups to perform on The Ed Sullivan Show, four young Black men singing so fine, dressed to the nines, making smooth moves in unison. David Ruffin, a former member of the group, spoke with me for a story in the February 21, 1976, issue of Melody Maker.

“The Temptations were individuals who happened to sing together,” Ruffin emphasized. “To this day, I always meet people and musicians who tell me how much the Temptations influenced them. It makes me feel good that others learned from us and a lot of the younger groups always acknowledge the Tempts in interviews.

“I never regretted any of the songs we did, and even the choreography on stage has been widely copied. I liked the dancin’ part of that group. Then you couldn’t just stand there and sing. The audience was moving, and you just reflected what was goin’ on. I’d like my association with the Temptations to be remembered as that we gave something. We helped young artists get in a position.”

While the Temptations were topping the pop charts with “My Girl” in 1964, they were also subjected to racial discrimination and harassment during tours.

“Some cats had to buy us food ’cause restaurants wouldn’t serve us, mostly in the South,” Ruffin lamented. “Things are much better today, but I can think of the times when I was driving independently of the group in my Cadillac, and the police, who didn’t like Black people with money or any fame, made me get out of town. They wouldn’t even let me stay overnight. I was visiting my mother, parked the car outside, and the cop said, ‘You can’t park it here.’

“Yet we always had respect from the musicians, and later, all kinds of kids went to our shows. We would rap and sing on the bus ride between concerts, and it was a lot of fun.”

In November 1974, for Melody Maker, I interviewed Bobby Rogers, a member of the Miracles and a Motown fixture since their inception in 1958, when Bobby joined up with his sister Claudette, Ronnie White, Warren “Pete” Moore, and Smokey Robinson.

“We used to tour with the Rolling Stones and people like Georgie Fame,” Bobby recalled. “During the breaks from touring, a lot of the groups would ask questions about certain songs on our albums. I remember when we filmedthe T.A.M.I. Show in ’64. Mick Jagger asked me about what I’d thought of the album James Brown Live at The Apollo, which was his favorite LP.

“Man, those early tours were a trip. Endless hours of bus rides and all these skinny English dudes asking us about the Tamla-Motown sound. I never realized how important or influential we were on groups like the Beatles and Stones.”

The Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show nine times (three live, six pre-taped or on video), and the Rolling Stones on six occasions (the last pre-taped).

“Ed Sullivan was a true American phenomenon,” observed Andrew Loog Oldham, the Rolling Stones’ producer-manager from 1963-1967 in a 2004 interview we conducted.

“Every country has one: a seemingly untalented nebbish with strictly local/national appeal. But say what you will, and we did, his musical booking decisions opened the eyes and ears of America and created a legacy/library for all future generations. And he’s the only dude I know who made the Rolling Stones change their lyrics.

“When the Beatles played The Ed Sullivan Show, [it was] that moment when American youth [were] feeling the subtext, feeling the great unspoken hurt of a nation still traumatized by the assassination of its president just a few months before. It’s an incredible moment: Suddenly, American youth had its own music, a reason to be alive.

“Barney Ales—the jewel in the crown. His efforts on behalf of Mr. Gordy and the artists were the primary reason the ‘Sound of Young America’ graduated all over the world.”

Ales was Berry Gordy’s right-hand man and Motown’s ultimate insider, whose job was to get the records played and the company paid. He rose to become executive vice president and general manager but remained in Detroit in 1972 when Gordy moved Motown to California. Ales became its president in Los Angeles during his return to the firm from 1975 to 1978.

“It was as really a battle in those days to get Black artists on network television in prime time,” Ales emailed me in 2016.

“Sammy Davis Jr. and Nat Cole were about the only ones—anyone else, they just weren’t accepted. But when the Supremes broke through, we knew we had an opportunity. They looked so great, as well as sounding great. And Harvey Fuqua and Maxine Powell did a wonderful job, grooming the girls, getting them ready for prime time.

“The Ed Sullivan Show was the real breakthrough: Sunday nights, millions of people watching. Once Sullivan took to the Supremes, we knew we were on the right track. And album sales picked up like crazy whenever they were on, so we always made sure to tell the distributors they needed to check their inventory.

“After the Supremes, we got everyone on Sullivan’s show: Stevie, Gladys, the Temptations. We had a good relationship with the producer, Bob Precht. He liked Motown, and Esther, Berry’s sister, used to take the dressing room keys afterward as souvenirs. They’re probably somewhere in the Motown Museum to this day.”