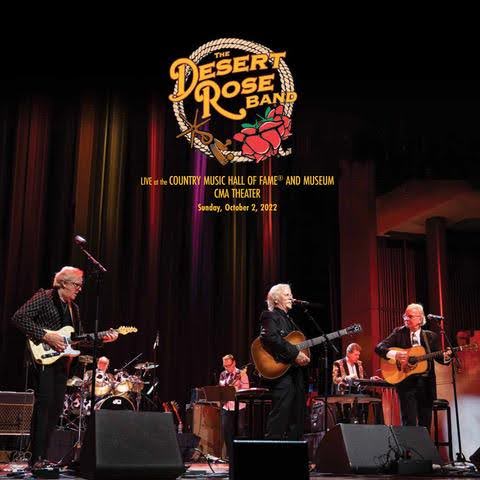

The Desert Rose Band, the popular country group co-founded and fronted by Chris Hillman in the 80s, reunited for one final performance in Nashville, on October 2, 2022 at the Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum’s CMA Theater. The acclaimed two-hour concert, recorded for posterity, was a highlight of the grand opening of the museum’s superb exhibition, Western Edge: The Roots and Reverberations of Los Angeles Country Rock.

Hillman has just announced that the 24-track, double live album, produced, mixed and mastered by Mick Conley, will be released on vinyl on September 5th from Friday Rights Management, LLC. The album is available through major online music retailers including Friday Music and TowerRecords.com. Executive producers are Joe Reagoso and the Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum. Associate producer is Connie Pappas Hillman.

It was a full circle experience for country-rock pioneer and Rock & Roll Hall of Famer, Chris Hillman, who founded The Desert Rose Band in 1986, along with Herb Pedersen, John Jorgenson, Bill Bryson, JayDee Maness and Steve Duncan. As a founding member of the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Brothers, Manassas, the Souther-Hillman-Furay Band, The Scottsville Squirrel Barkers and The Hillmen, among others, every decade of Hillman’s career was covered in the Western Edge exhibit, which will conclude its nearly three-year run on September 16. It traces the L.A.-based communities of visionary singers, songwriters and musicians who, from the 1960s through the 1980s, created and shaped the musical fusion “country-rock” and made an enduring impact on popular music. The opening events of Western Edge inspired Hillman to organize the farewell concert for the Desert Rose Band. It was the perfect occasion to celebrate the band’s rich history as musicians, their harmonies and the lasting impact of their songs.

Reflecting on the significance of the occasion, Hillman said, “October 2, 2022, would not only be the final concert for me after six decades of singing and playing music, but also the final performance for the Desert Rose Band. This night turned out to be a special one. We played together as if it was one of our very best shows in the early days. To have it recorded, and brought to life again for everyone to enjoy is a blessing. I hope everyone who listens will feel what we were all feeling that night.”

At the time of the live concert, it had been nearly a decade since the Desert Rose Band had played together. All surviving band members reassembled for the October 2022 concert including Chris Hillman (lead vocals/ acoustic 6 string guitar), Herb Pedersen (vocals/acoustic 6 string guitar), John Jorgenson (vocals/electric 6 & 12 string guitars/6 string bass/mandolin/acoustic guitar), JayDee Maness (pedal steel guitar) and Steve Duncan (vocals/drums), as well as Mark Fain (Ricky Skaggs’ long time bassist, replacing the late Bill Bryson). Commercially successful and critically acclaimed, the Desert Rose Band’s career had an impressive run during the eight years of their existence and were rarely off of the American Country charts. They celebrated two #1 singles and eight that made the Top 10. They also earned three Academy of Country Music awards (including Band of the Year) as well as CMA and Grammy nominations.

The band’s reunion concert performed songs spanning the group’s full career from its first single, “Ashes of Love,” to the chart-toppers, “He’s Back and I’m Blue,” “I Still Believe in You,” “One Step Forward” and “Love Reunited.” Other highlights included “Time Between,” Hillman’s first solo songwriting credit with the Byrds, Dusty Owens’ “Once More,” the Buck Owens’ classics, “Hello Trouble,” “Together Again” and “Under Your Spell,” Herb Pedersen’s “Our Baby’s Gone” and a rousing version of John Hiatt’s “She Don’t Love Nobody,” a #3 country hit for the band.

Michael McCall, associate director of editorial for the Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum and co-curator of the Western Edge exhibit said, “They have great songs, which is the primary thing. It had been eight years since they played together, but it was one of the best shows I’ve ever seen – they were just so on that night.”

The sold-out audience at the museum’s 776-seat CMA Theater featured an eclectic group of fans ranging from those who had first enjoyed the group in the 80s to younger generations and notable members of the music community, including Paul Worley who produced the Desert Rose Band’s first three albums. Praising their final concert, Worley said, “They were impeccable….it sounded like the records – it was perfect. I was blown away. It really was a super special night.”

The enthusiastic reception was unanimous, reinforcing what made the band so loved and respected in the first place. Three decades after their initial success, the Desert Rose Band delivered an exceptional night of music that will serve as a lasting legacy with the release of their live album.

Track Listing:

Side 1:

Ashes of Love (Jack Anglin, Jim Anglin & Johnnie Wright)

Love Reunited (Christopher Hillman & Stephen Hill)

One Step Forward (Christopher Hillman & Bill Parker Wildes)

He’s Back and I’m Blue (Michael L. Woody & Robert D. Anderson)

Time Between (Christopher Hillman)

Start All Over Again (Christopher Hillman & Stephen Hill)

Side 2:

Summer Wind (Christopher Hillman & Stephen Hill)

I Still Believe in You (Christopher Hillman & Stephen Hill)

Missing You (Christopher Hillman, Tom Dean Russell & Richard Gary Sellers)

Once More (Dusty Owens)

Our Baby’s Gone (Herb Pedersen)

Side 3:

She Don’t Love Nobody (John Hiatt)

In Another Lifetime (Christopher Hillman & Stephen Hill)

Story of Love (Christopher Hillman & Stephen Hill)

Hello Trouble (Orville Couch & Eddie McDuff)

It Takes a Believer (Christopher Hillman & Michael L Woody)

No One Else (Christopher Hillman & Herb Pedersen)

Side 4:

Desert Rose (Christopher Hillman & Bill Parker Wildes)

Together Again (Buck Owens)

Under Your Spell (Buck Owens & Dusty Rhodes)

Above and Beyond (Harlan Howard)

Hard Times (Christopher Hillman, Bill Parker Wildes, Jon Thomas Bradford)

Running (Christopher Hillman & Stephen Hill)

The Price I Pay (Christopher Hillman & Bill Parker Wildes)

Chris Hillman’s name is synonymous with the emergence of the retail and radio term Americana. From his work with Don Parmley and member of The Hillmen, playing alongside Parmley and Vern Gosdin, to his 1964-1968 stint with the Byrds, and co-founding with Gram Parsons the (1969-1972) country rock outfit, the Flying Burrito Brothers. Chris then partnered with JD Souther and Richie Furay for two albums in the seventies, followed by his series of solo albums leading to the Desert Rose Band.

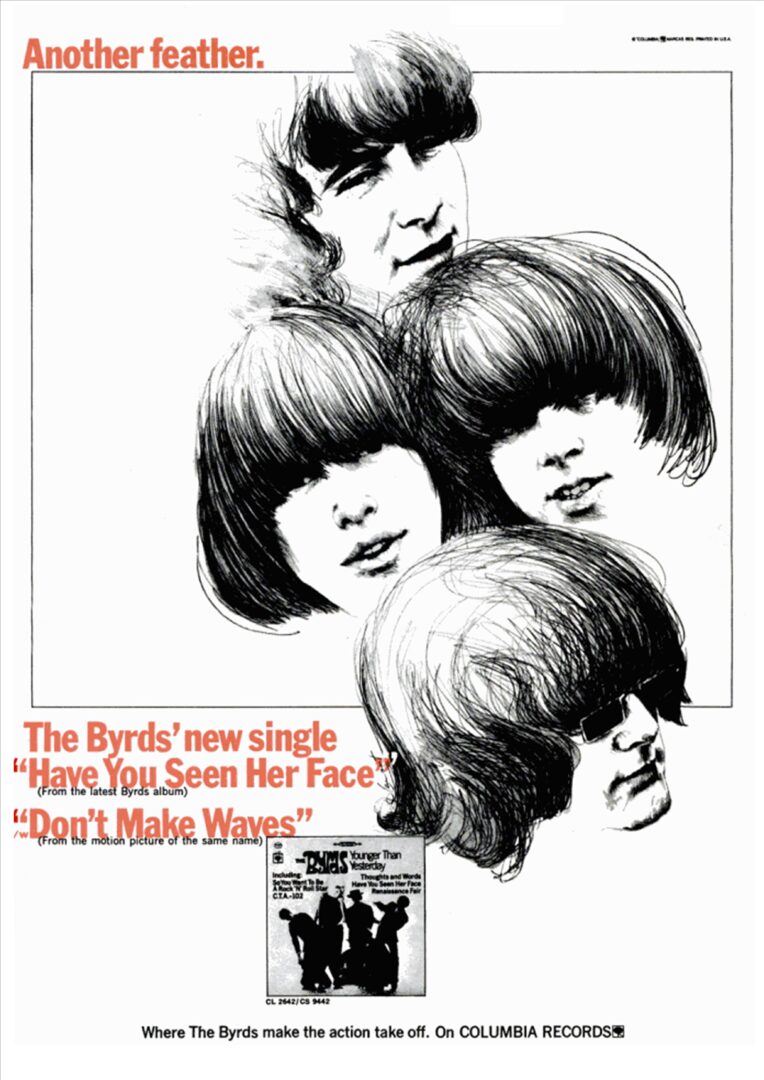

Often overlooked are Hillman’s songwriting endeavors, and a tune collaborator in the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Brothers, Manassas and the Desert Rose Band: “So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star,” “Have You Seen Her Face,” “Time Between,” “Bidin’ My Time,” “Christine’s Tune” (aka “Devil in Disguise”), “Sin City,” and his offerings in the Desert Rose Band, including “You Can Go Home.”

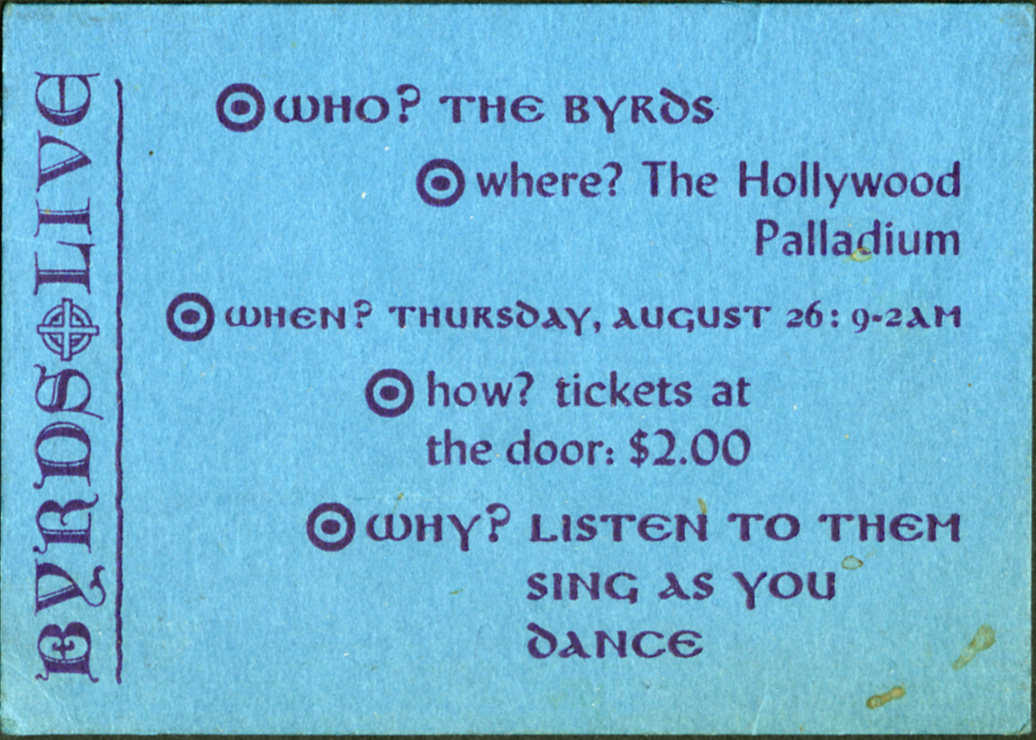

I caught the Byrds in 1965 when they did two concerts at Hollywood High School and Fairfax High School. Chris along with Roger McGuinn, were always the most accessible and friendly rock ‘n’ roll musicians when I would encounter them during 1966-1968 at the Canyon Country Store in Laurel Canyon or around clubs on the Sunset Strip.

Chris would tout guitarist Speedy West and praise Buffalo Springfield before their debut LP, and was too modest to promote his own group. Roger would cite Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan compositions. Their manager and Byrds’ early record producer Jim Dickson was an important musical figure in town and reminded us about the joint roles of music and activism.

Chris Hillman and Harvey Kubernik 2012 Interview.

Q: Let’s talk about the Byrds.

A: But there was also that period from 1959 to the Beatles in late 1963, that was a dead period. That was when folk music was just jumpin’ on its hind legs there. And so, who comes out of folk music? The Byrds, John Sebastian and the Lovin’ Spoonful, Stephen Stills, Richie Furay, the Mamas and the Papas. Four bands that were really successful with hits on the radio. Came out of folk music. And, of course, we were all emulating the Beatles to some degree at first. The Byrds certainly were. And then, I mean, my God, when I joined the Byrds they were still doing Beatlesque songs that Gene [Clark] was writing. But then we got into doing other material. But interestingly enough, out of that folk era, and I’m the guy coming out of the real traditional bluegrass, the other guys are coming out of the New Christy Minstrels. But those four bands took it and incorporated it and were successful but took it and incorporated it. And I think a lot had to do with the folk music emphasis on lyric. On a story. On that whole thing. And, the Beatles, when they became aware of Dylan and to some degree, listened to us a little bit, but they started to write deeper songs.

Before I was even in the Byrds, the first record I ever did was with the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers and we did the entire album in four hours. It was a good band. We went out to Griffith Park in Hollywood. Here we are lined up in a color photo shoot appropriate for our age. I’m a kid coming out of bluegrass. Where you didn’t move on stage and had a glum look on your face ‘cause you had to keep concentrating and playing at breakneck speed on a musical thing. Chris Darrow can attest to the ‘bluegrass showmanship,’ which is nothing there.

When the Byrds came along we did one of our very first publicity black and white shots and we’re in suits. I remember us doing that photo in the daytime and it might have been at Shelley’s Manne-Hole club in Hollywood. An older photographer and Guy Webster was at that session doing photos.

We did the Byrds’ Turn! Turn! Turn! cover at Guy’s studio at his parents’ house in Beverly Hills. Terry Melcher our producer at Columbia knew Guy, and they had done work previously. That’s where I first really met Guy. There we are. (David) Crosby is in his cape. McGuinn has got the glasses on, and the ever so fashionable hounds tooth sport coat. And then Gene (Clark) and Michael (Clarke) and I have our perfectly coiffed Beatle hair. It’s all in blue.

That LP cover and the music on Turn! Turn! Turn! was the breakthrough. The breakthrough record was ‘Mr. Tambourine Man,’ but the breakthrough album was that. ‘Turn! ‘Turn! Turn!’ is the most recognizable Byrds’ song way over ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ with all due respect. That’s the Byrds’ song people always remember. It was the LP cover I autographed the most. Our first album cover of Mr. Tambourine Man was Barry Feinstein, who was an old friend of Jim Dickson. Jim was our manager. I know the time period when the only delivery method was an album with LP cover art. The album cover meant a lot then.

In the Byrds, I was both a participant and a consumer as well. I would buy a record and go home and play it. It was a visual. On your first listening to of the album during that initial listening to the album you are looking at the cover photo and reading the liner notes. That was the package. The whole deal. An audio and visual experience. This includes picture sleeve singles. Which has never been duplicated with downloads and all that stuff. To some degree CD’s but by the time those came out it was harder to read the information. The seventies were the highlight of packaging.

Melody and lyric. One thing I’ve said before, and what our manager Jim Dickson drilled into our heads, the greatest advice we ever got, and he said, ‘Go for substance in the songs and go for depth. You want to make records you can listen to in forty years. That you will be proud to listen to.’ He was right.

‘Here we were rejecting ‘Mr. Tambourine Man.’ Mind you, I was the bass player and not a pivotal member. I was the kid who played the bass and a member of the band. Initially all five of us didn’t like what we heard on the Bob Dylan demo with Ramblin’ Jack Elliot. We were lucky. Bob had written it like a country song. Dickson said, ‘Listen to the lyrics.’ And then it finally got through to us and credit to McGuinn, mainly Jim (later Roger) arranged into a danceable beat. The Byrds do Dylan. It was a natural fit after ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ was successful.

Roger (then Jim) almost found his voice through Bob Dylan. In a way. Literally voice through Bob Dylan in a sense. And then we start doing some Dylan stuff. ‘Chimes of Freedom.’ Great song. ‘All I Really Want to Do.’ ‘Bells of Rhymney’ is my all-time favorite Byrds’ song. What song best describes the Byrds? I would say that. Because of the vocals on it. The harmony. Because of the way we approached the song and we had turned into a band. We had turned into a band with our own style. We went from doing Bob Dylan material and then we take ‘Bells of Rhymney” and it’s our own signature rendition of it. It’s not like Pete Seeger’s at all. It’s our own thing. And Michael Clarke, who was a lazy drummer but when he was on, he was great. And he’s playing these cymbals. A great experience. I just love that cut.

Q: The Columbia studio on Sunset Blvd. I loved those rooms. Former radio studio rooms.

A: Recording at Columbia studio. I remember that Columbia was a union room. The engineers had shirts and ties on. Mandatory breaks every three hours. Terry (Melcher) was a good guy. I didn’t really get to know him. I was shy. Columbia was comfortable to record in there. Terry was good. I liked him. I will say this, and on the Byrds albums I was not mixed back. Sometimes it worked. And I do have to say all five of us were learning how to play. Once again, coming out of the folk thing and plugging in. Ans we were all learning. Roger was the most seasoned musician, and we all sort of worked off of Roger. He had impeccable time. Great sense of time. His style and that minimalist thing of playing that was so good. He played the melody.

Gary Usher was an incredibly gifted producer to work with. Especially at the very end, and it was just McGuinn and I trying to finish Notorious Byrds Brothers. And Gary worked with us as another band member. Good ideas. Gary Usher brought us the Goffin and King ‘Goin’ Back.’ I don’t have a problem with that record. That was Gary bringing in a song that fit us like a glove. It was perfect and it’s Roger and I singing lead. It’s a little too pretty but it’s OK.

Q: You were at the June 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival. You saw the action, and the influence of that seminal musical moment which informed your subsequent songwriting and recording ventures.

A: Hugh Masekela at Monterey was one of the highlights, and earlier recording with him was one of the highlights of my life, in that, and David was on that session, we were playing with all these South African musicians, way ahead of Paul Simon. One of them was a piano player called Cecil Bernard. And he was the great inspiration for me to write ‘Have You Seen Her Face.’ There was something that connected with me and that was where I came out of my shell with that session. I came home and wrote ‘Time Between.’ I wrote songs that entire week after that session. And Hugh was working with Letta Mbulu, so some of that carried over to Monterey. And at Monterey we played ‘So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star.’ My ‘Have You Seen Her Face’ was influenced by a blind date Crosby had set me up with along with other young ladies.

I first heard the Buffalo Springfield before anyone else when Barry Friedman called me to come over to his house and listen to this band. I go listen to them, got ‘em a job at the Whisky, a year before Monterey. They were good live. They were better live than they were on record, right. And the Byrds were better on record than we were live. David sat in with the Buffalo Springfield at Monterey as well as with the Byrds. It did not bother me but it probably bothered Roger. I didn’t know until the 11th hour. My main concern was ‘where was Neil Young? Something had gone down.’

Jimi Hendrix…His playing. He was so out of left field that’s what got everybody. Not the burning of the guitar. That part was minimum. Here he was getting this tone on a guitar no one has heard before. My reaction at first was that’s a lot of noise. Bassist Noel Redding was really loud and the drummer (Mitch Mitchell) was playing nine million fills. But then that guitar tone comes in. And let me be honest with you: I didn’t appreciate Jimi Hendrix until 15 years afterwards. And I started to hear the blues stuff later on he did after all the show…He was such a good player.

Earlier, we got to know him. Mike Clarke and I went to Ciro’s and Jimi (then James Marshall) was playing guitar for Little Richard. Roger went as well. He was a sideman on the end of the stage playing left-handed. The best part of the night was we had these stupid suits that Dickson bought us and we left them in the Ciro’s dressing room and Little Richard’s band stole them. And we went, ‘Thank God,’ because they were like these velvet collar Edwardian Beatles suits, but there was Hendrix. You could not help but look at him at hear the sounds he was making on the guitar. And playing lead star in an R&B rock ‘n’ roll band you not the showcase. It’s the horn section carrying it. Very few guitar solos, mostly rhythm and stuff, but we said, ‘Who is that?’ Because the guy was so good. And then a year and a half later there he was at Monterey.

I thought Otis Redding was unbelievable. He played the Whisky A Go Go and Michael Clarke and I went, sat down with him, and he bought us a drink. Sweet man. Mike and I on the early Byrds tours, we used to take battery-operated tape recorders and loved listening to R&B and blues. One night at Ciro’s Mike played drums for Major Lance when his drummer didn’t show. And his hair is processed, and he turned around, ‘Hey drumma. Thanks man. Good job.’ ‘Six bucks! I remember watching Otis…I can’t compare it to anyone. Even my brief viewing of the Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl. They were so good but they had to keep stopping the show. Screams, but they were so tight. I remember watching Otis Redding. I had seen Sam & Dave at the Whisky. That was just a whole other level of professionalism. We weren’t entertainers. We weren’t supposed to be a Las Vegas act. That would have taken the whole mystery out of the Byrds or the Springfield, or any of those bands. But those guys were real professionals. They moved, they danced, and went into songs.

I saw Paul Butterfield at Monterey. We had worked with Paul the one time when the Byrds really came to the plate. Which when we did a week at The Trip and Butterfield’s original band and they were so good. Smoking. Michael Bloomfield doing answer solos with Butterfield on harmonica. They were so good and the Byrds…The one time in our whole career that we played every night at our peak. It wasn’t a competition. It was two different kinds of music. We went ‘oh my God. We played good.’ That was when the Byrds really jelled and really got together that week at the Trip. There were other times, but I always remember that so distinctly. Butterfield. Great band. I studied that first album.

I got to know Paul a little bit. I remember doing a music festival with Butterfield in 1969 in Palm Springs, with the Burrito Brothers. I remember walking with Paul to the promoter’s tent with Butterfield, and he’s got his brief case with a 38 Colt piece in it, and I said to myself, ‘this guy really did work on the south side of Chicago.’ Oh…Here we are in the peace and love bull shit and here he’s got his 38 loaded to go and collect his money!’ This guy is real. A real blues guy!

Q: 1967. Sweetheart of the Rodeo. The Byrds covered two Dylan tunes.

A: I have no idea why I got in the mail the two Bob Dylan ‘Basement Tapes’ songs in my mail. I sensed something was good there and I took them to McGuinn. And I wasn’t ready to sing those songs. I was not a good singer and the songs I sang on Sweetheart are mediocre at best. I wasn’t a good singer yet. I admit it. And it’s not going to haunt me to the grave. Because I learned how to sing. I loved the first Band album.

Sweetheart is an OK record. Gram brought two great sings to the mix: ‘100 Years from Now’ and ‘Hickory Wind.’ Really two of his greatest songs.

The original concept in 1969 was as plain as day. Here we are. We wanted to do country stuff. And the first two years with Gram was very good, very productive and on the same page. I think if I was to look back and say, ‘Well, I’d only…’and I don’t go there, but if I did, and it was a question presented to me, allowing him. Gram was far more confident. I was a musician. He wasn’t a musician. Gram was a charismatic figure. He was an interesting man at the time. I’m not saying he was a great singer. He wasn’t. He was a good singer on a couple of tracks, probably on the first album.

I knew Gram and I will always cherish a couple of years when we really worked together. But it turned into ‘Caine and Abel’ at that point. And about the trust fund. That was the downfall of Gram Parsons. Gram was handicapped big time with the annual stipend of $55,000.00. Because, this is what I have said, and you’ve read it before, it was a Tennessee Williams play. There was alcoholism, money, new money, backstabbing. A tragedy in front of my eyes. I was young but I was smart enough and well-read enough to go, ‘This is like some Southern gothic Faulkneresque Tennessee Williams thing unfolding here.’ As I started to lose him.

We were sloppy. The Burritos with Gram. I just had come out of a band that recorded ‘Eight Miles High’ that went from doing Bob Dylan songs to being able to do a song like that. To doing something that musical. And to be on a par with the Who or the Beatles. The point is we became a really tight good band. And I’m in the Burritos, and I’m looking at it not from a sterile place of it should be perfectly tight, but it wasn’t. We didn’t put any time into it.

And I must say, and I’m not padding myself on the back, when Gram left and Bernie (Leadon) and I took that band and we tightened it up and we made it a good band. And when Bernie left, we lasted another six or eight months. It became a musical band then. Did it have the magic that Gram offered? Not really. I still was learning how to sing. And Gram was an interesting guy. He had that thing. And I don’t know what the attraction is that other than he died in such a mysterious way.

Yes, he did some good songs. He had a bunch of good songs. Two songs, ‘Hot Burrito #1’ and ‘Hot Burrito #2’, those are Chris Ethridge songs. Chris Ethridge brought those in and Gram helped finish ‘em. ‘She.’ Great song. Ethridge. And with all due respect to Gram, he was a good collaborator. We collaborated well. He collaborated well with Chris Etrhridge and Bob Buchanan on ‘Hickory Wind.’ But they don’t get the credit.

So, I stopped worrying about getting credit. I don’t care. The Burritos took two and a half, maybe three years of my life. That wasn’t the only thing I did. I did other things afterwards that were valid and sometimes bordering on really getting it together. So, I always say the Burritos were an interesting band. It was like I was in a Mexican circus. I mean, with Gram it was really extremely entertaining most of the time. Until he got so drugged out, we had to get rid of him. It was funny. He was a great guy. Had a great sense of humor.

But also, on the other side of the coin I’ve always felt 1969 was the turning point when it got edgy. Meaning it got a little dark. The 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival was fabulous. The greatest rock festival, ever. I’m sorry. Not Woodstock. Not the Isle of Wight. It was Monterey.

After Monterey, what was a cottage industry and starting to develop into a profitable industry and then started to draw in…The ethics took a bit of a slide, not that they were always there, but what was a little cottage industry that was really run by music people, Jerry Wexler, the Chess Brothers, Ahmet, and Mo Ostin, and the people who loved music. And Monterey all of a sudden, the business started to really expand. The gates opened, the flood gates opened. And FM radio, and Tom Donahue was the FM guy and he brought that forward. You are looking at a profitable situation and we had the golden area of the recording industry and that the artists had more artistic freedom. They were signed, and kept around for 2 or 3 albums. It wasn’t platinum out of the box or you are out of the label. It was still this little tiny business that kept growing and growing. However, after Monterey, and I always say 1968, the next year is when everything changed, politically and socially, every which way in our society.

In August 1969 I was living in the San Fernando Valley in a house with Gram Parsons. And the news came on about Woodstock. I said to Gram, ‘That’s no Monterey!’ And it wasn’t. We were almost chuckling. I’m not denigrating it or putting it down. Monterey was the best.

Here’s the point. I was playing Monterey in ’67. Then Roger, Gram and I (Byrds) did a [May 24, 1968] benefit fund raiser [with Sonny & Cher, Mahalia Jackson, Roosevelt Grier] for Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena. And then in 1969 I play Altamont. My God. Within a couple year period.

Yes, Monterey did open up the record business. I was learning as I went along. I got quite an education. By 1972 I started to figure out publishing, and after working with Stephen Stills I started my own publishing company. The original concept of an A&R man, artist and repertoire, it wasn’t the publishing game that it became in the music publishing business. It was to sign the singer and find the material. And that’s when the music companies started to own publishing catalogues. It’s like Nashville. I got into Nashville in 1985, ’86 with the Desert Rose Band, it was a publishing world. That’s what made the town work. Singers were dispensable. And in rock ‘n’ roll, too. They really were.

Q: Why does rock and pop music of the sixties still resonate and impact audiences?

A: What holds up in that era were melodies. When you heard a new song on the radio the melody will catch you right away. You might hear a couple of lyrics then when you hear the lyrics if they’re strong and really saying something, yes, we do have songs that are sort of very catchy songs, but didn’t last long, like a fast- food meal. It was good when you ate it but wasn’t good later. That was it. The Beach Boys. Melody, melody, melody. Even though ‘Help Me, Rhonda’ lyrics fit the melody. It worked. It swung. That era…

When I do shows, I have people who come to see me play. Either they’re my age or they are young kids. 20 to 25, 26, who are enamored by the Beach Boys, Beatles, the Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers. I think that’s as big part of it and it was real and so honest. Of course, I’m preaching to the choir and telling you things you already know. But the record companies were run by music people. People who loved music. It was not a corporate monster. And they’d sign you and you’d be on the label for three or four albums, you know.

The sixties were wonderful. I look back at the sixties and it’s amusing to me. I don’t hold any grudges about people. I have no animosity toward anyone I worked with. But I look back and almost have a chuckle. People are obsessing over that period. Still to this day. Yes, youthful idealism. You have to be that way when you’re that age. Yes, we want one great world and it’s lovely. The human condition does not allow for that. OK. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have those wonderful things when you are a young person.