During 1974 as a music journalist, I attended a press conference in Beverly Hills at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel when George Harrison was announcing his first US solo tour. His remarks were published in the November 2, 1974, issue of Melody Maker.

On meeting the Beatles, Harrison said, “Biggest break in my career was getting into the Beatles. In retrospect, biggest break since then was getting out of them.”

Was he amazed about how much the Beatles still mean to people?

“Not really. I mean, it’s nice. I realize the Beatles did fill a space in the Sixties. All the people the Beatles meant something to have grown up. It’s like anything you grow up with—you get attached to things.

“I understand the Beatles in many ways did nice things, and it’s appreciated that people still like them. They want to hold on to something. People are afraid of change. You can’t live in the past.”

I first met Sir George Martin, the Beatles producer, at The Hollywood Bowl in 1996. He had sent me a note in the mail after hearing a recording I produced, praised my work, and invited me to the soundcheck at the venue when he prepared a tribute event that showcased the repertoire of the Beatles.

I spoke to Martin again in 2006 at Capitol Records Studio B. It was at a playback party for the Beatles’ LOVE.

George talked about a Frank Sinatra recording session he saw in this same room on his first visit to Hollywood in 1958.

The British EMI label sent him over the Atlantic after Martin was invited by Capitol label executive Voyle Gilmore to visit the American division. Martin described that ’58 booking when Frank Sinatra was backed by Billy May’s orchestra while actress Lauren Bacall was in attendance. The songs were eventually placed on Sinatra’s Come Fly With Me LP.

We chatted for a few minutes and I thanked Martin for discovering and signing the Beatles to their British record label deal. I complimented his persistent determination, along with Brian Epstein, in prodding Capitol Records to have faith in Martin’s groundbreaking Parlophone/EMI recordings with the boys in 1963.

One of Martin’s productions by the Beatles started playing in the studio.

Try hearing their sound over custom TAD monitors inside Capitol Records…George autographed an album, put his arm around me and smiled, “Pretty good stuff. Don’t you think?”

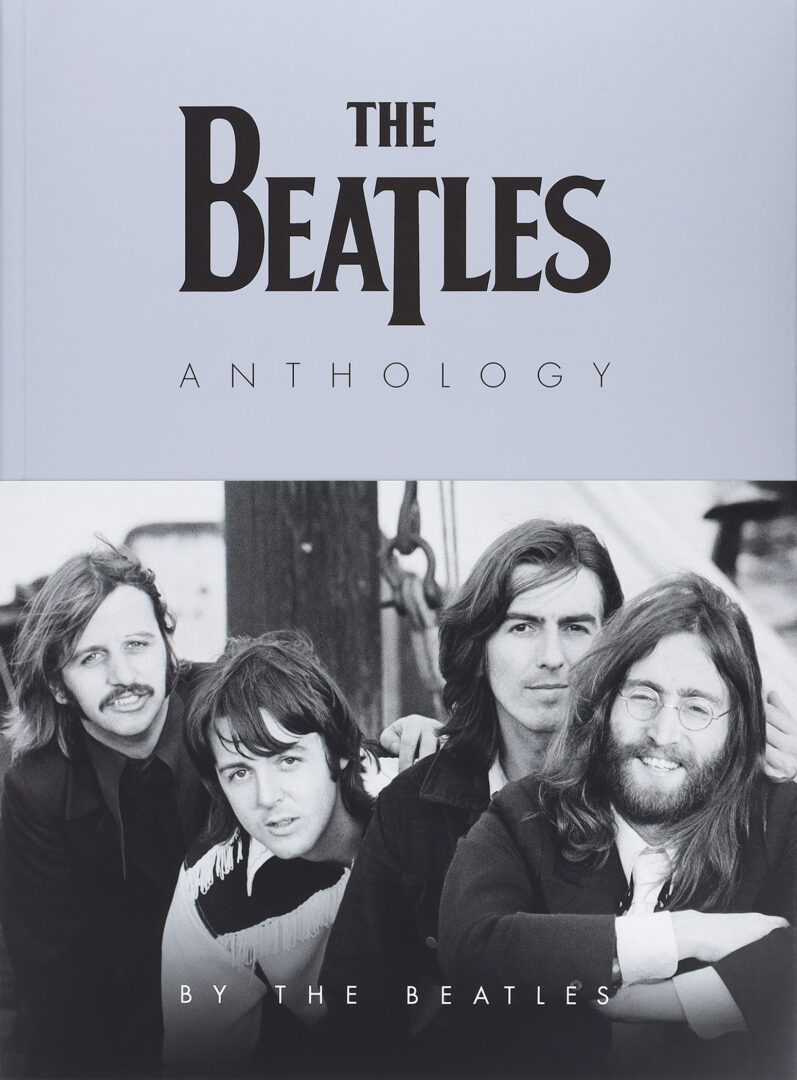

The Beatles Anthology music collection, restored & expanded to Four Volumes: 12LP Vinyl, 8CD & Digital Collections will be released November 21st by Apple Corps Ltd./Capitol/UMG for digital purchase and streaming, and in deluxe 12LP 180-gram vinyl and 8CD box sets.

Both box packages include the original sleeve notes for Anthology 1, 2 and 3; the new Anthology 4 includes track notes written by Kevin Howlett and an introduction compiled from 1996 interviews recorded with the Beatles’ close friend and adviser Derek Taylor. The Beatles Store’s exclusive editions for both box sets add four 12-inch band photo art cards in a numbered envelope.

The musical side of The Anthology Collection, originally curated by George Martin, now remastered by Giles Martin, in the form of three double albums of rare material, a shadow story to the one told in the documentaries. They are an enthralling insight into the early development of songs that became the recorded masterpieces that resonate just as loudly today as they did when they were first recorded. 4 x 2CD albums in gatefold digisleeves with booklets in slipcase.

The Anthology Collection 8CD set includes the three Anthology albums from the mid-1990s, remastered in 2025 by Giles Martin, plus a new compilation, Anthology 4. Containing 191 tracks, the collection’s studio outtakes, live performances, broadcasts and demos reveal the musical development of the Beatles from 1958 to the final single ‘Now and Then’ released in 2023.

Anthology 4 features 13 previously unreleased tracks and 17 songs selected from Super Deluxe versions of five classic albums. In addition to outtakes dating from 1963 to 1969, the album includes new 2025 mixes by Jeff Lynne of ‘Free As A Bird’ and ‘Real Love’. Furthermore, Anthology 4 presents 17 tracks that were previously unavailable on CD.

Each 2CD album in the set is housed in a gatefold digisleeve, with a 40+ page booklet featuring the original art, sleeve notes by Mark Lewisohn, and restored photos for Anthology 1-3; Anthology 4 has brand new sleeve notes written by Kevin Howlett alongside photos. The outer slipcase features the original Klaus Voorman triptych art, and a 3/4 O-Card image of the band with track listing.

8CD Track list: Anthology 1-3 track listing remains as per original releases produced by Sir George Martin. Anthology 4 contains 13 previously-unreleased recordings – versions of ‘Tell Me Why’, ‘If I Fell’, ‘Matchbox’, ‘Every Little Thing’, ‘I Need You’, ‘I’ve Just Seen A Face’, ‘In My Life’, ‘Nowhere Man’, ‘Baby, You’re A Rich Man’, ‘All You Need Is Love’, ‘The Fool On The Hill’, ‘I Am The Walrus’, and ‘Hey Bulldog’.

It also includes new mixes of The Beatles’ Anthology-associated hit singles: the Grammy-winning “Free As A Bird” and “Real Love,” given new life by their original producer, Jeff Lynne, using de-mixed John Lennon vocals.

Both new mixes are placed alongside the band’s most recent UK No. 1 hit single, 2023’s Grammy-winning “Now and Then,” the last Beatles song. All three singles were created from rudimentary home demos John recorded in the 1970s, later completed with vocal and instrumental parts recorded by Paul, George and Ringo.

For your reading enjoyment, Chronicle Books has just published The Beatles Anthology 25th Anniversary Edition. The landmark international bestseller—The Beatles’ own story, in their own words—reissued on the 25th anniversary of its first publication. The Beatles Anthology tells the complete story of the Beatles, from growing up in Liverpool to their rise to global phenomenon and ultimate breakup. Created originally with the complete support of Paul, George, Ringo, and Yoko Ono Lennon, with the words of John painstakingly compiled from sources worldwide, this 25th anniversary reissue offers the only story of the Beatles by the Beatles.

Engineer and producer Ken Scott began his engineering career at EMI Recording Studio. His first album job with the Beatles was The Magical Mystery Tour and then the White album. Scott would work with George Harrison on All Things Must Pass.

In 1972 he engineered and co-produced David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust. Scott has collaborated with Elton John, Pink Floyd, Procol Harum, Harry Nilsson, Duran Duran, Jeff Beck, and Mahavishnu Orchestra.

Earlier this century was Scott’s election to the Sound Fellowship of the United Kingdom’s Association of Professional Recording Services (APRS), a lifetime achievement award recognizing his contribution to music.

In 2012 Ken Scott published a memoir Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust.

Scott, a veteran of Abbey Road was at the console for recording sessions of the Beatles beginning in 1964. Initially placing tapes in the EMI studio library, he attended the “I Should Have Known Better” session, courtesy of engineer Norman Smith, and handclapped with Ringo and Paul for a take that wasn’t used.

Ken’s first day as a second engineer was June 1, 1964, during sessions for A Hard Day’s Night. Songs not utilized in the film: “I’ll Cry Instead,” “I’ll Be Back,” “Matchbox” and “Slow Down.” At Abbey Road he was “banding,” which was putting exactly five seconds between each track on the albums. He subsequently learned the aspects of mastering process. In 1965 Scott worked on Help! and Rubber Soul, before engineering the White Album.

Q: Before engineering dates for the Beatles’ White album, you spent a lot of time in the mastering lab that surely must have informed how we heard the Beatles in mono and stereo discs.

A: EMI training was so amazing because they had such a long time to get it together. The reason they had you do mastering and back then it was only called cutting, and they had you do mastering before engineering because vinyl has limitations. You can’t have too much bass on it. Otherwise, the record would jump. You can’t have things out of phase, otherwise the record would jump. Little things like that. Where with tape you can put anything on. So, they wanted you to learn the final product and the limitations of the final product before having the easy route of going onto tape. You get to learn those. The other thing you get to learn. And it was similar for all the engineers, when we first started to cut, to master, all we were doing were playback acetates. Those were seven inch 45 singles. They would only last for 10 or 12 plays.

Don’t forget: This is before cassettes and certainly before compact discs. So, this was the way the artist, the producer, sometimes the arranger got to heat what they worked on. So, we’d have to cut those and they weren’t going out to the general public or anything like that. If you screwed up it didn’t matter. That’s why you started off on those. And we all did the same thing. The first time we were on our own we’d put a tape on and think, “It needs a little bit more of the high end.’ So, we’d go full bore adding high end. “Yeah…That’s better. And now we need some low end.” We’d go full bore going low end. ‘Yeah…It’s close…We just need some mids now.” It took three days generally for people to realize you don’t need to pile on all of that EQ. You just need one notch at 10 and it’s fine.

Our job back then, cutting and mastering engineers, was to sound of the music across the way the producer, the engineer and the artist wanted it. We weren’t there to, excuse my French, “to fuck up the sound that they had got.” We were to continue what they had started. They knew what they were after and we had to accept what we received from them on tape was what they wanted. So, we just had to transfer that. To me a lot of the mastering engineers these days have never left that three-day period. And they will do everything they can to put their own mark on it.

Q: Norman Smith engineered all the Beatles albums ending with Rubber Soul. He left the Beatles to talent scout and become a producer. His first discovery was Pink Floyd. Geoff Emerick, Phil McDonald, Glyn Johns and yourself then engineered the Beatles’ sessions. I know Norman wasn’t some super radical engineer with the Beatles but he was responsible for some technical changes in their recording results.

A: Radical changes, no. Every single album he tried to make sound different. He pushed the envelope as far as he could. It was very difficult to make radical changes when he was engineering. Each album got progressively more radical if you like. A change in microphone placements. Absolutely. And using different microphones.

On the first album he wanted to capture them live in the studio. So, he set them up without baffles and without anything. It was as if they were on stage. That was the first album. Each one was different. To me, the way the Beatles got into experimentation a lot of that came from how they saw Norman changing things. Obviously, they caught the ball and ran with it. Unlike anyone else at the time. But he was the one I think that first instilled in them “it doesn’t always have to be the same every album. You can change it sound wise.” Obviously musically their experimentation with other instruments. Norman was the first pop engineer to record sitar at Abbey Road. He was amazing. He was always pushing it.

Abbey Road had their own pop shields for vocals. My belief is that they were made especially. I can’t tell you the pop shields around the microphones at Abbey Road made a huge difference, but it’s a combination. Everything starts in the studio. They were so good together vocally to start with and then that just made it so much easier for Norman to get it that much better.

Q: You were around for the Beatles tapes in the mastering lab and had the luxury of watching Harry Moss work on the Beatles. It was a period that began with mono and then stereo.

A: Mono was all we listened too. The stereo was just a throwaway afterwards until the White album. That’s when they got into stereo. And the group was there for the stereo mixes as well as the mono. Up to that point they were only there for the mono mixes. The Beatles’ stamp of approval was only on mono mixes. They all had their input. They all had ideas sonically. Even Ringo. He would want specific sounds. They were all into it and Paul a bit more than anyone else.

Q: During the White album Abbey Road’s Studer 4-track machine was replaced by an American made 3M-M56 8-track machine. Was this piece of equipment a huge departure or change?

A: Not to start with. The one thing with it when it first started it was much smaller and they had more of them. So, they could put the Studer in the control room. And we as second engineers got to sit in the control room for the entire session. Unlike up to that point when they only had had to be in separate rooms because there were three studios. And so, the machines could be plugged into whatever needed them. We were only ever in the control room during rehearsals. Then as soon as we started to record, we had to disappear down the corridor to this tiny little room and hear one track at a time and get instructions of what to do from this terrible talk back system. But, once the Studers became established and the Beatles started to demand more and more, then the Studers started to take over and become much more important.

Everything from being able to do 4 track to 4 tracks and give them more room to record things, then people like Ken Townsend coming up with ADT, automatic double tracking, or artificial double tracking if you want to call it, phasing and flanging, the Vari-Speed on the Studers became very important for the Beatles. They loved changing the timbre of instruments. George Martin was the first one to do that recording a half speed piano on “In My Life” on Rubber Soul. They learned from that how it changed the sound. And they wanted to manipulate sound.

Q: What about the sonic leap in sound when the Beatles went from tube to solid state board. Abbey Road was on a transistor board.

A: I’ve come to realize recently that the arguments we use about digital and analog are exactly the same arguments we used about tube versus Solid State. And the tube, the analog, is warmer. Whereas solid state, the transistor, was harder and harsher, much like we say digital is. But then I look back on it and I think one of my best recordings, Procol Harum’s A Salty Dog and Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon was done on that first Solid State desk. TG board, at Abbey Road. And Abbey Road was done on the TG and they all sound amazing. And we had arguments when it first came in. Looking back on it, that wasn’t that bad.

Q: What about tape stock? I’ve seen recording studios in Hollywood go from Scotch to Ampex to Ampex 456.

A: Anything they recorded at Abbey Road was done on EMI tape. EMI manufactured its own tape and it was incredible. It was really good. When they recorded outside, like the few tracks they did at Trident, or Olympic it would have been what the studio generally used. “Hey Jude” was one of the early things recorded at Trident and we had to re-EQ it at Abbey Road. “Dear Prudence” we actually got the mix and didn’t do any work on that. “Savoy Truffle” we did overdubs on and then I mixed it.

Q: Do you have any reason why the White album is so precise yet so flexible? I know the band, yourself and George Martin were employing an 8-track tape machine then. And they were not touring.

A: This was the first album and maybe the only album in which they had time restraints. And the reason they had time restraints was this was going to be the debut album out on Apple. There had been so much publicity about Apple there had been a date set for the release of the Beatles first album on Apple. So, it had to be finished by a specific day to the point where the last day that we worked on it. George was flying to L.A. the next day and he had to take masters with him. So, we were using three studios, two playback rooms. We used the entire building. And John Smith, my second engineer was in one of the playback rooms sorting out running orders with John and George Martin whilst I was in one studio mixing something. We were working out asses off right to the end. That was the first 24 hour session I ever did.

Q: What is it like watching something you worked on, or a band you first met in the studio in 1964 still have impact, influence and sales?

A: Oh boy. There’s a part of me that obviously is very proud of what we did back then. It’s amazing that it’s stood the test of time. For me it just goes to show how good the equipment was at Abbey Road was in that period. How good the technical staff was from the electronic wizards to the engineers to the mastering engineers. It’s a testament to the training that we had. How incredible it was. But there’s another part of me that is we should be talking about today’s music. Not 50 year old music. And unfortunately, because music is so bad today (laughs) we’re not. We have to revert back to things done 40 and 50 years ago. And that bothers me. It’s a mixed feeling.

Q: Do you have any theories why we are still discussing the Beatles’ catalogue?

A: Because of the changes going on in that period of time their music and they have become more important. They were very much a part of the major change within the western civilization. A lot of it stemming from the second World War. Because of the baby boom. Younger people were getting more of a say. More power. And that helped to change things, which they were a major part of.

I also feel that a lot of it is because it’s real. They were performances. It’s not like it is today where it’s all pieced together. Yes, we would do punch ins and that kind of thing, but there wasn’t copying one chorus and putting it in every chorus so it’s always exactly the same. They had to sing and play everything. And they had this ability, which so few other acts had, the closest I would probably come is U2, but they had this ability of being able to take the audience, their audience through changes. Without losing them. They always moved just enough that they could pull their audience with them and have the audience grow along with them.

Q: You saw the move from vinyl to cassettes to the CD format. What about the Beatles on vinyl?

A: To me it’s analog vinyl to CD. I find digital quite often cold compared to analog. There is a warmth and a depth if you like to analog, be it vinyl be it tape that we don’t get in the digital domain. We will eventually, but we’re not quite there yet. The whole point for me was that we had to move away from vinyl, at least for pop music, because the vinyl that was being used for albums was becoming so bad and so noisy that records were becoming thinner and thinner. It had to change. The way we listen to music had to change. And CD’s, even as bad as they were, when they first came out, were better than the quality of the vinyl at that point. I think now there’s probably more the availability of vinyl has improved so the vinyl being used for the records is at a higher standard.

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015's Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016's Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017's 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll TV Scenes) is scheduled for a late December 2025 publication.

Harvey Kubernik wrote the liner notes to CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival. During 2006 Kubernik appeared at the special hearings by The Library of Congress in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 he lectured at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in their Distinguished Speakers Series. Amidst 2023, Harvey spoke at The Grammy Museum in Los Angeles discussing director Martin Scorsese's The Last Waltz music documentary.

Kubernik is in The Sound of Protest documentarynow airing on the Apple TVOD TV broadcasting service. https://tv.apple.com › us › movie › the-sound-of-protest. Director Siobhan Logue’s endeavor features Smokey Robinson, Hozier, Skin (Skunk Anansie), Two-Tone's Jerry Dammers, Angélique Kidjo, Holly Johnson, David McAlmont, Rhiannon Giddens, and more. Harvey is interviewed along with Iggy Pop, Bruce Johnston, Johnny Echols, the Bangles' Susanna Hoffs and Victoria Peterson, and the founding members of the Seeds in director Neil Norman’s documentary The Seeds - The Seeds: Pushin' Too Hard now streaming online on Vimeo. This November 16, 2025, a DVD/Blu-ray is scheduled for release via the GNP Crescendo Company).