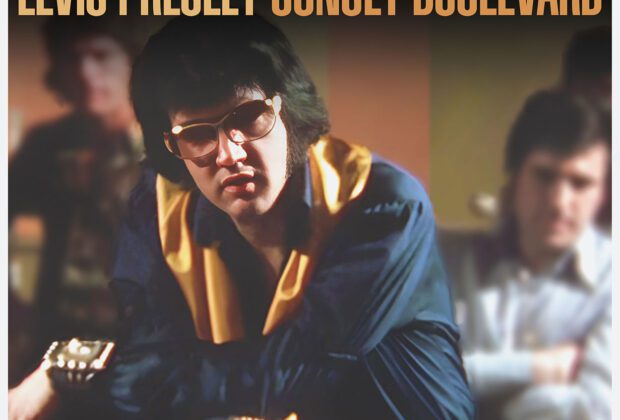

Elvis Presley will be the subject of a comprehensive collection, Sunset Boulevard, chronicling his 1970-1975 recording sessions and rehearsals at RCA’s landmark Los Angeles studios. The facility was located in Hollywood on 6363 Sunset Boulevard at Ivar Street. It is now the home of The Los Angeles Film School.

The 5-CD set spans 89 rarities – over half of which have never been released in the United States. It will be issued August 1, 2025, via RCA Records and Legacy Recordings, the catalog division of Sony Music Entertainment,

The June 13 Sony Music announcement describes Sunset Boulevard as “delivering illuminating perspective onto Elvis’ 1970s recording output.”

The all-studio set includes recordings of such Presley favorites as “Always On My Mind,” “Burning Love,” the 40th and final Top Ten single of his career, and such choice covers of “Green, Green Grass of Home,” “For the Good Times,” “I Got a Woman,” “The Wonder of You,” “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” “Something, “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “Proud Mary, and more.

The collection also features rare alternate studio versions of late-period gems like “Separate Ways”—widely seen as the most autobiographical song Elvis ever recorded— and the rollicking “T-R-O-U-B-L-E,” which channeled the groundbreaking signature vocal style from his earlier years.

The record label announcement further details the compilation. “The first two discs feature new and never-heard mixes from four-time GRAMMY winner Matt Ross-Spang – stripping all overdubs and delivering fresh insights in the process. Opening with seventeen classics from throughout Elvis’ time in RCA Studio C, these mixes provide an intimate glimpse into the ways his riveting voice interacts with material from the era’s greatest songwriters: Kris Kristofferson’s “For The Good Times” (a 1972 b-side first released in 1995), Paul Williams’ “Where Do I Go From Here” (from 1973’s Elvis), Billy Swan’s “I Can Help” (from 1975’s Today) and Don McLean’s “And I Love You So” (also from Today), among them. Ross-Spang’s stripped-down mixes equally bolster the seventeen studio outtakes that comprise the set’s second piece.”

Sunset Boulevard implements rare archival photographs and new liner notes from music historian Colin Escott, plus an introduction by longtime friend Jerry Schilling. As Escott writes: “Elvis and his wife, Priscilla, had separated at the beginning of [1972] and he was drawn to songs heavy with regret. The first was a keynote address. Red West had known Elvis since high school. He was Elvis’s friend, bodyguard, movie stuntman, and—occasionally—songwriter. Elvis never asked him for songs, but Red would pitch one anyway if he thought it might work. ‘Separate Ways’ came from my own situation,” West said later. “I was writing about my son, Brent. Then Elvis had his own situation with Priscilla, so [Richard Mainegra and I] changed the song to relate to Lisa Marie.”

Once it was recorded, Escott adds, “Elvis’s friend Jerry Schilling remembered that ‘Separate Ways’ resonated so deeply with Elvis that he played the tape incessantly after the session. “We listened to it for three hours in the studio. He’d just look up and shake his head. ‘You guys wanna hear it again?’ And we’d play it and play it. It was a real sad time.”

During the final three discs of Sunset Boulevard, listeners get a behind-the-scenes look at Elvis’ history-making Las Vegas residency — featuring Los Angeles rehearsals from July 1970 and August 1974 with his iconic TCB Band.

Notable among the 1974 recordings are two featured tracks that Elvis never made studio versions of: “Twelfth of Never,” originally a hit for Johnny Mathis in 1957 and “Softly As I Leave You” which finds him narrating a prologue about the song’s purported origins (inspired by his love of Charles Boyer’s narrated album Where Does Love Go). Elvis’ instinctive chemistry with the TCB Band is palpable throughout the rehearsals, perhaps owing to his decision to record with a road band for the first time during this era. See the complete track listing below.

Sunset Boulevard will also be celebrated at Elvis Week 2025 in Memphis – a special edition of the annual festivities, in honor of what would have been Presley’s 90th birthday year. Sony Music will host a Sunset Boulevard listening event at Graceland’s Guest House Theater on August 13 – featuring a Q&A with special guests and much more. For more information and tickets visit ElvisWeek.com.

The legendary RCA studios, a Hollywood temple of sound, had been home to Presley, Sam Cooke, Bobby Womack, Ann Margaret, Shorty Rogers, Gogi Grant, Jesse Belvin, Jack Nitzsche, the Walker Brothers, Charlie Greene and Brian Stone, Merry Clayton, Keith Richards, the Monkees, Darlene Love, Henry Mancini and Elmer Bernstein, Cal Tjader, Rosemary Clooney, Jascha Heifetz, the Astronauts, Jefferson Airplane, the Electric Prunes, and Arthur Rubinstein.

Producer Andrew Loog Oldham and the Rolling Stones recorded their monumental 1964-1966 albums at RCA with staff engineer Dave Hassinger. Brian Wilson produced the Beach Boys’ “Help Me, Rhonda” at RCA, and the Byrds recorded a version of “Eight Miles High,” straying from the confines of the Columbia Records studio also on Sunset Boulevard.

In July 2025, photographer Gered Mankowitz emailed me about RCA. He also was very generous sending over photos he took in his 1965 visit.

“Being able to spend a few days in the legendary RCA studios in Hollywood with Andrew Loog Oldham and the Rolling Stones was an exciting and appropriate ending to my first ever trip to the USA, and one I will never forget!”

In 2003 I interviewed award-winning engineer/producer Al Schmitt. He discussed the sonic achievements inside the RCA studios in his 1960-1966 RCA staff position. In late April of 1960, Schmitt engineered Presley’s first post-army film soundtrack for Paramount Pictures, G.I. Blues.

“Studio A and B were both the same size,” underscored Al. “They were big rooms, and then there was also Studio C, a smaller room. You could mix in either room. The studios had very high ceilings and a nice parkay floor. Very nice. One of the things that made them so unique was that we had all those great live echo chambers. I think there were seven of them.

“There was very little overdubbing then. The nice thing about doing everything at one time was that you knew exactly what it was going to sound like. When you started layering things you were never sure. Then a lot of experimenting came in and it took longer and longer to make records and the expenses went up, ya know.

“RCA had a great microphone collection. Just fabulous. Great Neumann and Telfunken microphones. Great RCA microphones. Plus, they had the great, original Neve console. And they were just spectacular. They were so punchy. There was a punch and a warmth and still one of the best consoles ever made. They were using a lot of Scotch tap then. Dave Hassinger learned microphone technique and how to use them, the most important thing.

“There were no isolation booths. None whatsoever. But we had gobos, we would move around. Like a separator where you could isolate things. We did have some small rugs that we would put down sometimes under the drums and things, but no too much.

“The Rolling Stones also started a situation where songs weren’t done in a standard four-hour session. They had the studio for weeks to do albums. That was new.”

I went to RCA studios for a couple of recording sessions by the Monkees. My mother Hilda worked at the Columbia studios from 1962-1972 in Gower Gulch, and in 1966-1968 for Raybert Productions on the lot, the producers of The Monkees. Once delivering sheet music of a tune on my skateboard to engineer Hank Cicalo when the office messenger wasn’t around, and another for Colgems music supervisor Don Kirshner or Lester Sill, both executives at Screen Gems Music Publishing.

In 2008 recording engineer Hank Cicalo reminisced to me about the RCA world.

“I had done some projects with arranger Shorty Rogers for Lester Sill. They were looking for an engineer to work with the Monkees, and my name came up. That’s how I fell into the project. I had a meeting with Lester and songwriters Bobby Hart, and Tommy Boyce. We went out and had lunch or dinner. They discussed what the project was about, and they were just about doing the pilot. Nobody knew what was going on. It was a TV show with a lot of music, and that’s all I knew about it.

“The one song I didn’t engineer at RCA was ‘Last Train to Clarksville,’ which was done by Dave Hassinger. I’d be booked for a month at a time, doing just the Monkees’ things. It was a lot of work. There was always this endless pressure of trying to do three or four musical numbers for each show while they were still shooting. We were working long hours at night, and whoever wasn’t shooting the next day could stay longer and do a vocal or this kind of thing or that kind of thing, working Saturdays and Sundays.

“For that period, because of the hours we were working at night, and also mixing, and also going through a very interesting change at that time, we would do a track on three-track or four-track, and then go from one machine to another machine, adding a vocal. We also went from four–track, to eight-track, to sixteen-track in that two-year period. It was the very beginning of multi-track, and we all progressed in a new medium as well. We were able to stack voices and double up voices without losing quality. It was a very interesting period.”

From 1973-1980 I was at RCA on occasion, visiting the record division or inside the studios. I recall a 1973 college seminar at one RCA room with composer Henry Mancini. Hank invited a class of college students to a mixing session, coordinated by Grelun Landon, the well-respected head of public affairs at RCA Records.

I viewed the first live broadcast of Elvis’ Aloha from Hawaii Via Satellite in January 1973, along with several RCA Records employees. Imagine hearing Elvis Presley and that TCB band through those Altec 604E Super Duplex monitors inside RCA Studios!

I saw Elvis Presley in 1970 at the Inglewood Forum as a paying college student. Between 1972 and 1976, Landon arranged for me to attend or review five Elvis concerts, and meet Presley’s manager, Colonel Tom Parker. I was also introduced to several of the TCB band members.

I had a previous Elvis Presley sighting on a Saturday afternoon during summer of 1967, when I was a teenager, in Dr. Morris Feldman’s Picwood dental office in West Los Angeles near the M-G-M studios in Culver City. Presley arrived in a Rolls Royce, flanked by two big guys. Dr. Feldman told me Elvis had broken a tooth during the filming of his 1968 movie Speedway.

I’ve always felt the reflective aspect of Elvis Presley’s 1970-1975 recording endeavors were influenced by Paramahansa Yogananda, born Mukunda Lal Ghosh, (January 5, 1893-March 7, 1952), who was an Indian Hindu monk, yogi and guru whose teachings of meditation and Kiya Yoga reached millions of people through his organization Self-Realization Fellowship. His teachings of yoga provided unity between Eastern and Western religions. During 1925 in Los Angeles, he established an international center for SRF.

Yogananda’s life story, Autobiography of a Yogi, was initially published in 1946, and expanded by him in subsequent editions. It’s been a perennial best seller having sold millions of copies, and translated into many languages. George Harrison and photographer Henry Diltz would gift the book to friends and musicians.

In 1950, Yogananda held the first Self-Realization Fellowship World Convocation at the international headquarters in Los Angeles. He also dedicated the beautiful SRF Lake Shrine in Pacific Palisades, that has since become one of California's most prominent spiritual landmarks. It survived the 2025 fires that engulfed and demolished Pacific Palisades. A barge and a gas-powered water pump were key to the sanctuary’s survival and everyone was evacuated from the premises.

By the late sixties, Elvis Presley was looking for a new spiritual and musical road map just before his memorable Elvis…’68 Comeback Special done at NBC studios. Presley had visited Self-Realization Fellowship center on Sunset Blvd. near the Pacific Coast Highway in Southern California and devoured Autobiography of a Yogi from the movement’s founder, Paramahansa Yogananda. Presley and his wife Priscilla also had a friendship with Daya Mata of the SRF retreat in the Mt. Washington area in East Hollywood. Sir Daya Mata, born Rachel Faye Wright, was President and spiritual head of SRF from 1955 to 2010.

In Elvis and Me: The True Story of the Love Between Priscilla Presley and the King of Rock N’ Roll, by Priscilla, with contributions from Sandra Harmon, Priscilla mentioned her husband’s fascination with spirituality. Elvis made several trips to the Mount Washington retreat for sessions with Daya Mata hoping to attain the highest form of meditation.

“As Elvis’ fascination with occult and metaphysical phenomena intensified, [his friend] Larry introduced him to the Self-Realization Fellowship Center on Mount Washington, where he met Daya Mata, the head of the center,” Priscilla wrote. “She epitomized everything he was striving to be.” According to Priscilla, “Mata resembled Elvis’ mother, Gladys Presley.” Elvis would call her ‘Ma.’”

Jerry Schilling is the author (with Chuck Crisafulli) of Me and a Guy Named Elvis. Jerry was a longtime insider/adviser and trusted Presley friend. In 2007 I interviewed Schilling, one of the executive producers on HBO’s Elvis Presley: The Searcher. Until recently, he managed the Beach Boys.

“Elvis was a seeker,” reinforced Schilling. “He did go to the Bodhi Tree (spiritual book store in West Hollywood that opened in July, 1970). There was a part of our group that did not like that. I was in the minority with [Presley’s hair stylist and spiritual adviser] Larry Geller. Elvis was open to show a spiritual and vulnerable side. He was into that. What I loved about it was that through his spiritual quest I got to know the man even deeper. We would go to SRF in Pacific Palisades and Mt. Washington in East Hollywood many times.”