In SMiLE: The Rise, Fall and Resurrection of Brian Wilson, author and documentarian David Leaf delivers an unparalleled oral history of the album’s journey from creation to near-oblivion and triumphant rebirth. Following Pet Sounds in 1966, Wilson embarked on SMiLE, an ambitious project blending diverse musical styles and modular recording techniques.

However, internal band conflicts, Wilson’s deteriorating mental health, and music industry pressures led to its shelving in 1967 by Capitol Records.

In 2003, the idea of reconstructing SMiLE was met with uncertainty: Could Wilson do it? Would Brian take the stage at London’s Royal Festival Hall to unveil SMiLE? The answers came on February 20, 2004, a victorious night that cemented Wilson’s legacy.

Drawing on exclusive interviews with Brian Wilson, Van Dyke Parks, and key figures from both SMiLE eras, Leaf provides a behind-the-scenes look at the album’s history. His proximity to the events—having lived through SMiLE’s reconstruction while producing a documentary about it—infuses the book with unparalleled authenticity and depth. While the Beach Boys’ early hits defined the sunny side of American rock, SMiLE tells a deeper story—one of genius, struggle, and redemption.

David Leaf is a Peabody and WGAW Award-winning writer, director, and producer known for critically acclaimed films like The Night James Brown Saved Boston, The U.S. vs. John Lennon, and the Grammy-nominated Beautiful Dreamer: Brian Wilson and the Story of SMiLE. He has also worked on HBO’s Emmy-winning The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend A Broken Heart and is completing a feature documentary on Dion (Dion: King of the New York Streets). As an author, Leaf is celebrated for the Grammy-nominated The Pet Sounds Sessions and his definitive biography, God Only Knows: The Story of Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys & the California Myth. Since 2010, he has been a professor at UCLA’s Herb Alpert School of Music, teaching courses on rock documentaries, songwriting, and the Beatles. In 2024, he launched a new class, Good Vibrations: Brian Wilson & The Beach Boys. The New York-born Leaf is based in Southern California.

I first met David Leaf in 1976 when we stood in line at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium to buy tickets for a Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band concert.

I have an intimate relationship to his new book. I suggested the publisher and contributed an essay.

In 1962 I saw the Beach Boys play “live” inside a Culver City record shop. At age 10 I was introduced to the Candix Records promo man Russ Regan, then working for Buckeye Records Distribution, who in 1960 suggested the band’s moniker. In 1970 as UNI/MCA label Vice-President, the visionary A&R man then signed Elton John for North American territories.

I’ve known Brian Wilson since 1965. In 1974 I wrote the review in The Los Angeles Times Sunday Calendar section of the Beach Boys’ Endless Summer double album released by Capitol Records.

In 2004, Brian supplied the back cover jacket testimonial for my first book This Is Rebel Music, published by The University of New Mexico Press. During 2007 I wrote the program booklet text and conducted an interview with Brian Wilson for his Pet Sounds 40th anniversary tour. I’m thanked on the 2011 Capitol Records SMiLE box set. I also did the interview with Wilson in his 2009 book collaboration with Sir Peter Blake, for the limited edition That Lucky Old Sun for Genesis Publications. In 2024 Brian penned the introduction to an award-winning book my brother Kenneth and I wrote and assembled on SMiLE photographer, Guy Webster, Big Shots: Rock Legends and Hollywood Icons, published by Insight Editions.

Now that my Muhammad Ali-like introduction is over, I’ll happily admit, I learned so much new stuff about Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys, record label machinations and local geography.

I’m the child of Hollywood, but how could a New Yorker transplant write and deliver such a probing regional deep dive on an already exhaustively well-documented subject?

One afternoon in early April, I was so absorbed reading Leaf’s book I actually missed watching the second half of the NCAA UCLA/ Connecticut Women’s Basketball Final Four televised match!

In David’s examination, I revealed after 45 years that one evening in West Hollywood in the late seventies, when I “saved” Brian Wilson from a dangerous and life-threatening car accident.

Leaf requested the story for his study, and I was encouraged by several Wilson associates to mention this in my essay.

I was “Walking on Sunset” as the John Mayall song goes, going to eat at Power Burger, and thrust into action, just doing my civil duty, racing into traffic on Sunset Blvd. as a bewildered newly-separated or divorced 300-pound Brian Wilson, clad in only a bathrobe, was meandering in the middle of the street near Fairfax Ave.

Thankfully, in elementary school, I was a scrambling Fran Takenton-type quarterback in football games, and provided immediate and somewhat heroic assistance to a dazzled pedestrian in the center of the street completely oblivious to dozens of cars honking their horns and weaving around a lonely and disoriented figure in distress.

I then realized it was Brian Wilson dodging oncoming vehicles speeding in the always crowded intersection who was going to be splattered all over the 90028 asphalt! I swooped into the action and we somehow made it to the curbside on Sunset and Curson Ave., avoiding the lookers and hookers.

We then walked to get a cup of coffee at 7-11 and around the corner to our longtime pal Rodney Bingenheimer’s nearby apartment down the block and listened to Phil Spector recordings as Brian appeared to be more coherent.

We subsequently schlepped Brian over to David Leaf’s pad in Santa Monica, the only adult in the room, who took over our rescue mission.

For decades I assumed David brought Brian into the local Santa Monica or UCLA hospital for observation. My 1959 Cadillac was leaking coolant and at the time I wasn't a member of The Automobile Club of Southern California. The last thing anyone needed during this crisis was looking for a pay phone if my car stalled.

I only found out in 2024 that David felt Brian was safe and calm, and only wanted a couple of slices of pizza before David drove him to a new residence at the beach that had no furniture whatsoever when they arrived.

David Leaf and Harvey Kubernik 2023 and 2025 Interview

HK: Can you discuss the genesis of this expedition?

DL: I was making my film, Beautiful Dreamer: Brian Wilson & The Story of SMiLE during its rebirth and extensively interviewed everybody involved, including Darian Sahanaja and Van Dyke Parks, who give us an insider’s explanation of how it was put together. The book includes a chapter of fan memories of the stage debut when Wilson first played SMiLE live as well as a mini-anthology of a dozen original essays about what the album meant and means to those writers/journalists/musicians.”

HK I never thought of a touring Brian Wilson. I’d go over to Brian and Marilyn Wilson’s home in the seventies and we’d sit around and Brian would play piano. Since 1999, how does it feel that almost a quarter of a century as his solo career was expanding, we can still see Brian Wilson onstage. Going on airplanes, taking bus rides, backstage food. Did you anticipate Brian Wilson would become a touring artist?

DL: Best thing that happened. Well, not only did I not anticipate it but when the first tour was announced for 1999 and what we thought. Brian going on tour with his band, The Wondermints at the core of it, but some great Chicago players. That allowed everything that's happened since 1999 to bear fruit, because not only was he able to revisit and bring to life his greatest Beach Boys album Pet Sounds, but because he became a touring artist, he was able to find a way to finish SMiLE. And I don't care what crystal ball you had, but at any point in the 20th Century, nobody thought that was going to happen. What we believed going back to the 1970s, was that if and when he ever finished SMiLE, great new music would come out, and that happened as well when he premiered That Lucky Old Sun at Royal Festival Hall in London. And it was like ‘Wow. We were right.”

HK: Years ago, at Brian’s 60th birthday party, I asked him why England became his spiritual second home and why the country embraced his work much wider than America? He replied, “Because they appreciate good music more than Americans. The music goes to their heart. Those people are more in tune with and more grateful to hear music than America. When you are 85 years old, and that’s not for a while, you’ll still love music just as much, or even more, when you are 85. London is like that.”

England and SMiLE debuting there? It’s a Southern California creation. The Beach Boys did a live ‘69 album there, and I respect and UK media coverage. England getting SMiLE live before America?

DL: Starting with Derek Taylor in 1966 with his “Brian Wilson is a genius…I think” campaign, the British have always loved the Beach Boys. Hiring Derek Taylor as the Beach Boys’ publicist was the group’s first big deal entry of the Beach Boys into the UK media consciousness. Because you had a man who had been the Beatles’ publicist and would again be the Beatles’ publicist and his campaign in ‘66/’67 was spectacular.

HK: Was it a bit over the top?

DL: Well, it was only over the top in that SMiLE didn't come out, but it was a great publicity campaign. It sometimes went awry. There was a clever illustration from a UK rock mag, in the first edition of my book, of a hand like a marionette with the headline “Are the Beach Boys Brian Wilson's puppets?” Which wasn't right. They were his vocal instrument, his messengers.

So, generations of music writers and music fans grew up having seen the headline “Brian Wilson is a genius… I think” and it eventually became “Brian Wilson is a genius.” Pet Sounds was very successful in the UK. And Keith Moon of The Who was a big Beach Boys fan. But probably more than anything, what you had is a country filled with clouds imagining what it was like to be on the west coast.

And so, Beach Boys music was sunshine, in a country where it rained a lot. And that never changed. So, in England, there were the early writers on SMiLE here in the states like Jules Siegel and Paul Williams, especially. There was the Leonard Bernstein CBS-TV program featuring Brian singing ‘Surf’s Up.’ But in’67, the Beach Boys were dismissed by the Rolling Stone/San Francisco cognoscenti who looked at the Beach Boys as something of a joke.

HK: You were there for personal salvation as well as sending out kind of a service signal to support Brian Wilson's unfulfilled journey, as far as the specific SMiLE album project that never came to fruition.

DL: When you say it like that, it feels like I was Commissioner Gordon sending out the signal for Batman.

I was able to extensively interview Audree Wilson, the Wilson brothers’ mother. I spoke in depth with the people who were actually there, many of whom are no longer with us like Gary Usher and David Anderle, as well as some of the key people who still are like Rich Sloan and Tony Asher and Van Dyke Parks. I did a long interview with Chuck Britz, the engineer on most of the Beach Boys best records. And spoke with musicians who played on the sessions. I talked to the people who were there when it happened.

Last decade I interviewed Mike Love. We discussed his vocals on the Tony Asher songs for “Pet Sounds” and later Van Dyke Parks lyrics on “SMiLE.”

“Well, you know, I’m both a lead singer and a background singer. I’m a team player as well as a lead singer, you know. No, there’s not really a difference. I mean, Tony Asher did some phenomenal lyrics on Pet Sounds.” He did great lyrics. And Van Dyke just got for me got a little obtuse. I call it acid alliteration. OK? That was the term I use. And people think I’m being disparaging and an ass hole but the fact is that I look at lyrics as a way to communicate to people.

Like, when I first heard the track of “Good Vibrations” I said, “Wow. How are the people in Omaha gonna take this?” Cousin Brucie, the biggest DJ in New York, said when he first heard “Good Vibrations” he hated it. He got to love it but originally, he hated it. He told me because it was so different.

Here’s my frame of reference. “Good Vibrations” was the chorus Brian and I came up with and the lyrics I wrote went to number one. Thank goodness. And that was fabulously successful, phenomenal and the biggest hit of the ‘60s for us. And we had some pretty good size hits.

But then “Heroes and Villains” came out. And it went top forty something. I don’t know what it went too. The thing is, awesome track, the thing stops. And Bruce recalls, being in a club in England and having the record played. I don’t know if he had it with him or had it played. And he was in a club when “Heroes and Villains” was played. Everybody was dancing and they stopped dead. And also, the lyrics to me as far as commercial appeal did not cut the mustard. Is that the way you say it? Anyway, it didn’t rise to the level of commercial appeal. Which I admit I am both appreciative of the artistic part of things but I also want it to be successful. That’s me. That’s Mike Love.

I love “Vege-Tables.” That was fun. Paul McCartney came to the session. That was delightful. That’s a sweet song. I love the whimsicality of “Vege-Tables.”

“Surf’s Up” is a beautiful, beautiful song. With Brian at the apex of his vocal abilities and powers. Before he smoked four packs of cigarettes a day because he thought singing with his high falsetto voice was effeminate. And I think it’s my nature along with his nature that combines to be incredibly artistic but also lyrically. I try to relate to the widest possible amount of people without losing sight of the concept of the song.

I came up with the lyrics to “Cool, Cool Water.” Using the word gas as a superlative. There’s a lot of cool double entendres. That song is such a trip to listen too. Some of the songs found their place on subsequent albums. And the “SMiLE” project itself ultimately because of Brian shelving it, it was never that cohesive, you know.”

I had nothing to do with shelving the “SMiLE” project. I sang on all the songs, you know, that I could. And there’s some beautiful music. I mean, “Wonderful” makes you cry. I just remember the tracks that Brian did were incredible.

“Heroes and Villains” reminded me and made me think of “The William Tell Overture.’ You know it’s so dynamic and powerful. And “Wonderful” is so beautiful and sensitive. And although I didn’t agree with Van Dyke’s lyrics on every single thing, I thought he did a marvelous job on that.

Q: Just before the formal “SMiLE” recording sessions really started, you and Brian collaborated on “Good Vibrations.” Walk me through the process of the writing session and the recording. The first version was done at Gold Star studio.

A: Well, the thing is, Brian was experimenting with various versions of the “Good Vibrations” track. He didn’t have the lyric, but he had a phenomenal track. In fact, when I first heard the first version, it reminded me of the R&B outrageous groove of James Brown’s band, you know.

Q: The kind of records you heard in the late 1950’s and early and ‘60s on Los Angeles radio stations like KGFJ and KVOX.

A: Exactly. Really incredible. The R&B kind of groove to it. And the bass did what it did and it gave me the idea to say, “I’m pickin’ up good vibrations. She’s giving me the excitations.” Excitations may or may not be in the dictionary, but you know, I did it anyway. And so, I came up with that chorus line and lyric and wrote all the words.

And because he was experimenting with various sections that were ultimately put together and what came out as the single, I didn’t actually write the lyrics until the day we were on the way to the session. And I dictated while I was driving to my then wife Suzanne, who was pregnant at the time. And she wrote it out.

See it was in the midst of the flower power psychedelic era, as you would know. And I think I’ve always felt “Good Vibrations” was the Beach Boys’ tomb to the peace and love and flower summer of love type of deal. It just kind of, in our way, made that statement. Because it was talking about something. Originally, we were talking about, you know, girls, surfing, beach life, cars and all that kind of stuff. But with “Good Vibrations,” we began to come a little more subjective rather than objective. Meaning more feelings and more subtlety.

Like, when I first heard the track of “Good Vibrations” I said, “Wow. How are the people in Omaha gonna take this?” Cousin Brucie, the biggest DJ in New York, said when he first heard “Good Vibrations” he hated it. He got to love it but originally, he hated it. He told me because it was so different.

Here’s my frame of reference. “Good Vibrations” was the chorus Brian and I came up with and the lyrics I wrote went to number one. Thank goodness. And that was fabulously successful, phenomenal and the biggest hit of the ‘60s for us. And we had some pretty good size hits.

But then “Heroes and Villains” came out. And it went top forty something. I don’t know what it went too. The thing is, awesome track, the thing stops. And Bruce recalls, being in a club in England and having the record played. I don’t know if he had it with him or had it played. And he was in a club when “Heroes and Villains” was played. Everybody was dancing and they stopped dead. And also, the lyrics to me as far as commercial appeal did not cut the mustard. Is that the way you say it? Anyway, it didn’t rise to the level of commercial appeal. Which I admit I am both appreciative of the artistic part of things but I also want it to be successful. That’s me. That’s Mike Love.

I love “Vege-Tables.” That was fun. Paul McCartney came to the session. That was delightful. That’s a sweet song. I love the whimsicality of “Vege-Tables.”

“Surf’s Up” is a beautiful, beautiful song. With Brian at the apex of his vocal abilities and powers. Before he smoked four packs of cigarettes a day because he thought singing with his high falsetto voice was effeminate. And I think it’s my nature along with his nature that combines to be incredibly artistic but also lyrically. I try to relate to the widest possible amount of people without losing sight of the concept of the song.

I came up with the lyrics to “Cool, Cool Water.” Using the word gas as a superlative. There’s a lot of cool double entendres. That song is such a trip to listen too. Some of the songs found their place on subsequent albums. And the “SMiLE” project itself ultimately because of Brian shelving it, it was never that cohesive, you know.”

Al Jardine interview:

Brian had other ideas and was very specific about keeping it out of that project for his own reasons. Obviously it had a lot to do with “SMiLE.” He wanted “Good Vibrations” to be the leadoff single for “SMiLE.”

When the 8-track machine showed up They brought in a new machine with more tracks and we loved it. ‘Cause we were able to stack more and more vocals with less sound. Something they call sound to noise ratio. And, so, it should have sounded clearer, less bouncing, combining to open up tracks where you combine them. The engineer would always leave a track open for a bounce to combine your vocals and bounce it to another track. Once it is bounced it is bounced and you can’t take it back.

Of course, what I didn’t know during “SMiLE” was at Columbia was that they would always keep a copy in case the bounce didn’t work out. So, at some point you could go back and do it again. So, we have fortunately, lots of safety reels. Or we used too, but I understand a lot of that stuff is missing. Because maybe they figured that once it was mastered they didn’t need them anymore. Who the hell knows. At any rate, we went from 8-track to eventually 16 which was really cool. It was interesting to see the technology grow and the width of the tape change.

Carl and I were locked in with Brian on the top and Mike on the bottom. And we all seemed to gravitate to whatever Brian extrapolated out of the either. Whatever was there we just grabbed it. We knew exactly where we were supposed to be. It’s weird. I always floated in on top under Brian and on top of Carl and he carried his low tenor above Mike’s baritone. It was just a beautiful blend. And when I left for a short while I thought Dennis’ blend was beautiful. It was a struggle for him. It did not come to him naturally to be a background singer. But I enjoyed the family harmonies. Towards the end of his career Dennis came into his own. And then he really started coming into his own. It’s like a dormant quality that began to emerge. Gritty. He was just a man’s man. And he could pull it off. Nothing like the real thing.

Mike’s baritone is fantastic. He still has the pipes. Carl as a singer, a vocalist. He was so similar to Brian in his vocal range. A little fatter, though. He had a fatter voice. Brian was more of a razor edge voice. So you had that compliment, that same tonality, but with different edges. Different contours if you looked at it on Pro-Tools. It sounded so innocent and nice. There was something magical about it. A family singing together. The family voices.

Bruce Johnston is an important part of the “SMiLE Sessions.” We do forget about Bruce. He was there every night like I was. Those early morning hours before the sun came up during a lot of this stuff. A very precise and organized singer. Very excellent pitch and would sing those very high and long whole notes. Not the high edgy ones like Brian but more round notes. More round like Carl. Very strong and very clear. When you are a vocal group, you have to have pretty good pitch, otherwise things start to rub.”

During 1966 I first heard about Smile in The KRLA BEAT a weekly music periodical published in Southern California.

In late ’66 there was further news about an upcoming new LP by the Beach Boys actually called Smile, mentioned at a record convention Capitol Records held promoting their first quarter 1967 products.

I remember waiting for many months for this album to arrive at Wallichs Music City in Hollywood. I kept reading about this “Long Player” being recorded at various studios including Gold Star, United Western, RCA, Columbia and Sunset Sound. I had no idea the former Beatles’ publicist Derek Taylor was spearheading this publicity campaign in newspapers and national/international music weeklies.

Thankfully, as school started at Fairfax High in September 1967, and “Good Vibrations” was all over the local radio airwaves, I purchased a copy of Smiley Smile. At the time I had little data of the machinations and often delayed marketing of the original Smile retail configuration Brian Wilson was carrying around in his head.

In 1965, ‘66 and ’67 I would see Brian and his wife Marilyn occasionally at Fisher’s Hamburgers, in the 3rd Street and Fairfax Avenue Town & Country shopping center. One time they were with actor Tony Dow of Leave It To Beaver fame. Marilyn introduced me to Brian and Tony and told me she and her two sisters had gone to Fairfax, and her parents, like mine, were from Chicago.

As a child of Hollywood, my mother worked at Columbia Studios in Gower Gulch on Sunset Blvd. 1962-1972, and from 1965-1968 was based at Raybert Productions, who produced The Monkees television series. She was a secretary and in the stenography pool and helped type the weekly TV scripts for two seasons. Every month I would spend hours after school on the lot or navigating Sunset Blvd.

I recall in 1966 mulling around the Moulin Rouge venue, then known as The Hullabaloo Club, The Kaleidoscope and The Aquarius Theater. Brain was inside the Sunset Blvd. venue with the Beach Boys teaching them the intricate vocal parts of “Good Vibrations” as they were preparing to tour.

It was in late 1965 at RCA studios on Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood where Brian Wilson met Andrew Loog Oldham, who was producing a session with the Rolling Stones for their Aftermath LP.

In a 2004 dinner conversation, Andrew remembered the encounter, “Brian mentioned to me he would one day, ‘write songs that people would pray too.’ Brian put his heart in his music at a time when we were all using other muscles."

The Wilson effect can also be found on “What to Do,” a selection on the Stones’ Aftermath. An homage to the Beach Boys, particularly their stacked vocal harmonies. Mick Jagger initially remarked during that session to Andrew, ‘What do you want me to do? Brian Wilson?’

“Good Vibrations” was brilliant, but cold,” suggested Andrew.

“Genius has to function with a beat in the third ear, and his third ear was on Ritalin. A lot of folks went along for the ride because it was pretentious, or at least lofty. And, in a way, that belonged to the times. We had had the sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll, and now we desperately wanted to make a difference, be it at Kent State or Grosvenor Square. So, in a very warped way, Brian was on the money. I liked the Beach Boys again with Wild Honey and 20/20.”

Acclaimed photographer Guy Webster took many photos of Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys, including 1967 SMiLE period shots. In 1965 Andrew Loog Oldham invited Webster to do the cover photo shoot of the Rolling Stones’ High Tide, Green Grass.

During 2014, Guy and I chatted at his Venice studios.

“I love Brian. Child-like innocence, and he was playful. And I believe in that. One of the things about studying Buddhism all my life is getting that playful side, exposing it and don’t be afraid of it and let it out. Everything Brian did I loved. Even the silly songs like ‘Surfer Girl’ I thought were brilliant.

“I saw Brian take pop music into a new direction. I feel it an honor that I was at the recording session for the vocals of ‘Good Vibrations.’ Oh my God. I had chills up and down my arms and back the whole time. I had never seen anything like it and to be in that recording session and to see them practice in the halls getting their harmonies. Holy shit. That was a real treat. It’s one of the highlights of my musical life. Van Dyke Parks is the lyricist with Brian on SMiLE. He’s brilliant. I did the cover of his Song Cycle album.”

In 2004, It was announced that Brian Wilson and the Wondermints were actually going to perform and record Smile. I was invited by Brian and songwriter Andy Paley with Wilson family and friends to a Burbank, Ca. rehearsal studio to watch Brian and his band do their curated Smile repertoire. I had a nice chat with actor Tony Dow.

Smile was being actualized on stage. When the full-dress run through for the UK tour dates were done in front of family, guests and friends, I know there was a sense of relief for Brian that some of his 1966 Smile vision was going to be seen and devoured by an audience in England that was fully aware of the saga of Smile.

I enjoyed the Brian Wilson-centric Smile concert and album this century. I had thought Smile would be something which would happen posthumously for Brian and that classical orchestras were going to start performing sections and selections from Smile. But, as I viewed the rehearsals, I realized for Brian, what a joyous and liberating feeling for Smile to finally be heard in a live setting, his Wilson-driven recording, and a film of the UK premiere, distributed commercially.

Nick Walusko: Vocals and guitars

Darian Sahanaja (our "musical secretary") also made nice and solid contributions (beyond playing keyboards, vibes, and singing) He made sure that intros and ends of songs worked flawlessly. I believe Darian's suggestions and contributions are integral to the overarching cohesion and much of the sonic beauty of Darian has a true and natural knack for seeing the big picture musically and pursuing an artistic goal to its fruition.

I must say that Van Dyke's poetic contributions are marvelous. His magical words ring clear like an early '60s Hollywood Boulevard color postcard--inviting even the longtime residents to take a second look; tourists may enjoy it, but there's so much going on here that it requires a thorough investigation, and even then, one is left feeling that you've only explored the edges of cliches and not the real deal. L.A. is like that. There's a mystery that's both enticing and somewhat frustrating to acknowledge--like a human soul!”

In 1963, Van Dyke Parks was living in Laurel Canyon. I loved to Laurel Canyon because I enjoyed the hedge sensibility and the idea that it was a borderline to a checkered urban existence, that there was still a kind of a natural environment. I had a nostalgia, which I was introduced to in 1953 when I came out here to be in a feature picture, The Swan, with Grace Kelly. I went through the Garden of Allah in 1955 when I stayed and lived at the Chateau Marmont making $1500 a week, $450.00 in addition, non-taxable, to be a feature player in a movie. The Garden of Allah was across the street.

I liked Laurel Canyon’s natural declivities and I liked the geography and geology of it. The botany. A beautiful place to be. That really is what determined my interest in it and why I returned there, preferring it to the expansive L.A. basin.

I think of the Hollywood Bowl and the first thing I think is of is sitting there with Rock Hudson and Marilyn Maxwell, who was his date. The head of MGM obviously staged that event. I love the venue…I especially enjoyed the Deco period in developing [Los Angeles], and the Hollywood Bowl to me just satisfies on so many fronts. As a matter of fact I opened for [conductor) Carmen Dragon once.”

Parks was signed to MGM Records in 1964 as a solo artist.

“I really think being in Laurel Canyon, and the social nexus that we created, had a lot to do with certain people coming to the canyon and being aware of it. Danny Hutton, David Anderle, myself.”

I wonder where pop music would have gone if Smile was issued a handful of months before the Beatles’ Sgt. Lonely Hearts Club Band?

What other recording artists in the mid-sixties rock genre would have been doing if whole sides of albums were exclusively devoted to specific concepts, or suites with fire and water references? Where pop music would have been in 1967, '68, and '69, with free form and underground FM radio?

As for Smile, there are complicated stories of the American interior. Nothing is more bio-regional than a composition by Brian Wilson and Van Dyke Parks recorded in Hollywood on Sunset Boulevard or Santa Monica and Vine Street with instrumental tracks supplied by Local 47 Hollywood Musicians Union members. The session cats were never referred to as The Wrecking Crew back then.

You get elements of the movie Shane, the old west, plus the omnipresent influence of the beach. A words and music examination of the toil on our sacred soil.

What a sense of accomplishment it must have been for Brian and his band in 2004 to perform Smile the way he wanted it presented.

However, I admit Smile to me will always have a murky and misguided history. And, there will be concerns about origin, session dates, sequencing and destiny.

Kirk Silsbee: “I see SMiLE as both a culmination of Brian's work up to that point and a transcendent burst, breaking the bonds of the Beach Boys format, which had been chafing at him for some time. It was a suite of American music and a travelogue of Americana: regional music forms and signposts. Its polar centerpieces are "Heroes and Villains" and "Good Vibrations." The first played with the idea of America as the ethnic melting pot and the conflicts of a pluralistic society. The second parlayed romantic love with spiritual love. Both, in a very real sense, revolutionized the AM radio single through the brilliant manipulation of the studio. Phil Spector made three-minute symphonies for kids, but his records were largely static. Brian invested these two AM "symphonies" with movements, interludes, and arrangements that displayed sweep, counterpoint and musical tension. But the central formal peg is "Surf's Up," the masterpiece art song that redefined what an art song could be, giving the concept Aquarian relevance, as no other rock music auteur had.

“SMiLE contained ideas and gambits that he'd played with or hinted at earlier. One was his connection to the Great American Songbook writers who came before him. We all know about Chuck Berry's bedrock for "Surfin' USA" but on the Surfer Girl album Brian had a tune called "South Bay Surfer"--to the tune of Irving Berlin's "Swanee River." In SMiLE, he refers to Jimmy Davis's "You Are My Sunshine" and Johnny Mercer's "I Wanna Be Around." Clearly, Brian was seeing himself outside the rock music warren. Ethereal monastic harmonies, transistor radio doo wop, musique concrete, baroque vocal counterpoint, the high and lonesome sound, Hawaiian music--they all have a place in this suite.

“To a great degree, Brian's collaborators defined his music. The hot rod songs he wrote with Roger Christian were different from the "Pet Sounds" meditations that Tony Asher supplied lyrics to and the Van Dyke Parks collaborations--which SMiLE exemplifies--are unique in turn. "Surf's Up" in particular and SMiLE in general are shot through with graceful lyrical allusions that speak of eras gone by. Dreamy imagery ("calumniated ruins domino") and orchestrations that were beyond Brian's ken enlarged his concepts and gave the work a depth that outweighed the contribution that a mere lyricist could add. The nautical song fragment, replete with sea-faring jargon and Van Dyke's characteristic puns was an example of that new element to the Wilson canon. Likewise the turn-of-the-20th Century orchestral interlude provided connective tissue that changed the scope of the work.”

Dr. James Cushing: The extreme uniqueness of SMiLE is, for me, its dominant characteristic. On the "inside" level, music / lyrics / orchestration, it sounds literally like nothing else (well, maybe a few moments of Pet Sounds blended with Gershwin and, ultimately, Bach cantatas filtered through The Four Freshmen); the melodies and the linkages between them are unlike anything else anyone in "pop" was doing before or since. It's musically coherent -- melodic themes recur in a foreshadow / flashback way much more deftly than anything on Sgt. Pepper or Tommy (only Zappa's We're Only In It For the Money rivals it in that regard -- please don't bring up Pink Floyd's The Wall).

“As a lyrical-musical total statement, what does SMiLE "mean"? I reference Hart Crane's The Bridge but NOT about trying to "raise SMiLE to the level of High Culture" like Christopher Ricks tries to do with Dylan. Wilson's already high culture! I think SMiLE and The Bridge are both brave art-essays on the subconscious, poetic meaning of the contradictions of American history and the American character. The section called "Powhatan's Daughter" is most relevant to the Wilson/Parks collaboration. America is imagined as Woman, "an innocent girl from the Spanish and Indian home of the Heroes & Villains," and the white settlement is the forced marriage that endures through ups and downs, from cabins with barnyards to the Grand Coulee Dam into Hawaii, ending on a note of hope tinged with anxiety -- "gotta keep those good vibrations happening with her" because it would be horrible if we couldn't... Crane's version is darker and more violent (the marriage becomes a sacrificial dance) but the dream-logic that connects the poem's sections anticipates the SMiLE connections; both are intuitive and musical, not rational-chronological, so if you want "unified coherence" from SMiLE or The Bridge (or Eliot's The Waste Land or WCW's Paterson) you will not get it... These modernist works offer a critique of the assumption that "unified coherence" is a necessary value anyway, given the fragmented nature of modern / American experience.

“Uniqueness on the "outside" level of SMiLE's impossibly weird history! Smiley Smile, 1967; Good Vibrations Box Set Disc 2 Tracks 18-28, 1991; Brian Wilson Presents SMiLE, 2004 -- and this year, the most famous UNRELEASED album in rock history will BE RELEASED FOR THE FOURTH TIME. May we enjoy the idea of a modern-art masterpiece existing in distinctly different versions? Can our heads get past the idea that the "creator" of this "opus" has approved all four of these releases, hence giving them nearly-equal status? Can we stand the idea that this 2011 release is simultaneously the ORIGINAL version and THE MOST RECENT version, which will therefore have to battle for shelf-space and ear-time with three EARLIER but NOT ORIGINAL versions? Has any artist messed with our sense of time this way?”

Gary Pig Gold: "Outside the safe confines of my basement 'listening room,' it sure wasn’t easy being a Beach Boys fan(atic) back in the very early 70s Toronto suburbs. Before that Endless Summer broke over us one and all, that is. For instance, there was the time I snuck a copy of the just-released Holland onto the turntable at a typical highschool Friday night beer-and-weed soirée, most pleasantly surprised as the room slowly quieted to attention while 'Sail On, Sailor' played …until, that is, when eventually asked who was spinning I was instantly met by a chorus of 'the Beach Boys? Take that [expletive deleted] OFF!'

"Plus, come to think of it, I’m still not absolutely sure why many to this day fail to fathom my unshakeable love of Beach Boys’ Party! …mail-ordered, at considerable expense I’ll have you know, direct from the Oxford Street HMV Store in London ten years after the fact (regrettably minus the 15 Full Color Fan Photos, alas).

"But! It was two extended volumes of reading that mattered – a full reprint of Tom Nolan’s landmark 1971 Rolling Stone study I uncovered in a Beach Boys songbook, followed several years later by David Leaf’s California Myth – which not only began to put all those pieces of the SMiLE saga scattered across various long-players into some sort of context, but fully burst open not just my ears, but my mind to the magic, musical and otherwise, of what was, and remains, Brian Wilson.

"Today, it still warms my soul to recall the tearful standing ovation awarded Van Dyke Parks as he rose, introduced by Brian, from his seat at the 2004 Carnegie Hall SMiLE recital. Two old soldiers in heartfelt recognition and appreciation with this particular battle of theirs, against all odds, finally and indisputably won.

"After all is said and sung however, most reaffirming and gratifying to me is the too true knowledge that, after seeking out or perhaps simply stumbling upon it, somewhere someway out there today, and I’m sure over countless days to come, someone brand new is breaking into a SMiLE for the first time and forever falling deep under its spell. Completely."

In a 1977 interview for the now defunct UK music weekly Melody Maker, I wanted to know how Brian wrote his songs.

“I don’t carry a notebook or use a tape player. I like to tell a story in the songs with as few words as possible. I sort of tend to write what I’ve been through and look inside myself. Some of the songs are messages.”

In 2007 Brian and I noshed at his favorite eatery, and he addressed the apparent unfinished Smile venture.

“I always knew the songs were strong enough… ‘Heroes and Villains,’ ‘Surf’s Up.’ Like on ‘Heroes and ‘Villains,’ and ‘God Only Knows…’ There weren’t songs on the radio with God in the title. Then there were no songs with ‘Villains’ on the radio.”

Brian volunteered the main reason why Smile did not come out as initially scheduled in 1967.

“Because Van Dyke and I decided that we were too far into it and we didn’t write anything but snippets. Except for ‘Heroes and Villains,’ we junked it. They weren’t complete.”

“Working with Van Dyke is not easy at all. Because he is a perfectionist. So he wants it his way and the right way. So, I go, “Yes, Van Dyke.” He’d say, “OK, but that’s not what I had in mind.” “OK.” I never argue about things. I’ve always liked what he’s come up with. That’s the thing. Always. I’d never say that sucked ‘cause that would hurt his feelings. He’s a gentleman and a scholar. A very bright person.

“I love “Heroes and Villains,” too. The magic of Van Dyke’s lyrics and my lead vocals. It’s a pretty youthful lead.

Q: Where did the title “Good Vibrations” come from?

A: From my mother. In Hawthorne, California. She said, dogs bark at humans because they think of good vibrations,” they pick up on bad vibrations but don’t mind picking up good vibrations. My mother got the title for it

Q: “Surf’s Up.”

A: Van Dyke and I wrote that at my house. It was about 11:00 in the morning, and we had a sand box with a piano in it and it took us 30 minutes to write it. Maybe an hour and a half. We just wrote it really spontaneously. We title songs after the lyrics. I never wrote a song on guitar or bass. We were trying to get across the feeling of children. How much their love means to people. Van Dyke Parks is the greatest lyricist I’ve ever heard. His lyric writing is poetic.

“Leonard Bernstein had me play ‘Surf’s Up” on TV. He told someone he liked it. A song has to work on the piano before it goes to the studio. On the keyboard you can see what you’re writing. You can hear and see it.

Q: A bunch of the songs on “SMiLE” began with you and Van Dyke Parks sitting in a sandbox in your living room. The piano was right in the sandbox. How did the sandbox inform the songs being developed?

A: It brought in a beach vibe to us.

Q: “SMiLE” is not exclusively about the beach.

A: I know, but that was why we did it anyway. “Cause we wanted a departure and wanted to feel like we weren’t in some house.

Q: There’s a section in “SMiLE” on the tune “Do You Like Worms,” where at the end there is this Hawaiian segment happens, and actually serves as some re-occurring theme in “SMiLE.”

I believe you and Van Dyke intended for “SMiLE” to visit or end in Hawaii. Van Dyke had a tropical section constructed during “Do You Like Worms” with a lap steel and vocal doubling. You tried to explain the sound once after Van Dyke described the recording, “It is so December 6, 1941” and that blew your mind.

Maybe it’s a logical extension, going back to earlier songs for the Beach Boys, where water is a thread. You had a previous song, “Hawaii.”

A: “Hawaii.” I was in Hawaii when I wrote it on a piano. “Catch A Wave.” That was my attempt to create a group style that mixed falsetto, mid-range and bass and backup singers all at once.

When we started “SMiLE,” Van Dyke told me that there were going to be nature elements like fire and water. He told me that.

Q: How did you initially react when those concepts were laid on you?

A: Well, I think, first I said, “What do you mean?” Fire, water, earth and air. He said, “We can do a little of each.” After that I can not remember what we did.

Van Dyke and I were very quick at music. See, the thing is, Van Dyke knew music also. He also helped me with the music. I wrote most of it but he gave a direction for me.

I was using both sharps and flats and he was like, “Hey. Try another key.” And it all sort of happened because the key made all the difference.

Q: How did it feel writing music to this type of American imagery that Van Dyke was providing?

A: I got so close to his images that we’d touch upon the very actual mood of early America.

Q: Guitarists Barney Kessel and Glen Campbell are heard on “Good Vibrations.” You employed them on “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” on Pet Sounds.

A: I said to myself, “I’m going to have these guys play directly into the board instead of going out into the studio.” And they plugged their instruments into the recording console direct. They are on ‘Smile.’ That’s how we got that sound. I also did that on “California Girls.” My brother Carl played a 12-string on that and we plugged him into the console and he did his thing. Every now and then I’ll do that. It sounds more mellow and it is something I can’t quite describe but it is much more mellow than an amp.

Q: You brought in the Theremin instrument in “Pet Sounds” for “I Wasn’t Made For These Times” and it is even more prominent in “Good Vibrations” and tracked for “SMiLE.” I know during “Pet Sounds” you saw jazz guitarist Barney Kessel at a session at United Western recording with a Theremin player for a science fiction soundtrack. You then requested Barney to do a session the very next day and to bring the Theremin guy. Barney said, “I’ll ask him and see if he’s available.”

A: Yes. I first discovered it when I was a little kid. My mom and dad had a friend who had a thing where you put your hand out and get a sound that goes higher and lower. And then I found out about what they call a band Theremin where you slide your finger across a band. And I used it. It is an instrument that you use sparingly.

Q: Do you remember the first time you heard the final mix of “Good Vibrations” in the studio.

A: At the playback, all the guys said, Hey Brian. This is a number one record.’ I said, ‘You know what? I agree. I think this is gonna be a number one record.’

Q: What is the one thing, the specific element in “Good Vibrations” that still resonates with you when you hear the recording?

A: Mike’s bass part was the one. Mike’s voice on it was the thing that sold me on it.

Mike’s singing got us famous. Because his voice has a quality to it that goes hand and hand with the song. He was the appropriate singer for the song.

“Carl Wilson is my favorite rock ‘n’ roll singer. He had a resonate voice and he had a lot of energy and power in his voice. In which I didn’t have or Mike, or the other guys. Carl and Dennis were both my brothers and my artists.

“Dennis as a singer... First of all, he had an energy. Right? Second of all he had a nice quality about his voice. Coupled energy with a sweetness and that was his whole trip.

“Bruce Johnson. He is not an energy singer. Bruce is a sweeter singer and a better falsetto.

Q: What is the one thing, the specific element in “Good Vibrations” that still resonates with you when you hear the recording?

A: Mike’s bass part was the one. Mike’s voice on it was the thing that sold me on it.

Mike’s singing got us famous. Because his voice has a quality to it that goes hand and hand with the song. He was the appropriate singer for the song.

A: I heard ‘Heroes and Villains” and thought to myself, “Hey! I did that with Van Dyke!”

Q: You told me a few years ago you loved that record because of the magic of Van Dyke’s lyrics and your lead voice on the record.

A: It’s a pretty youthful lead. Because the damn thing is so together and cohesive. It comes together so beautifully that people can’t resist lovin’ it.

Q: I remember when the Beach Boys rehearsed “Good Vibrations” on Sunset Blvd. at the former site of The Moulin Rouge that eventually was known as The Aquarius Theater. Before the stage play “HAIR” was booked in that building. You were teaching the group the intricate vocal parts because you were not going to performing in concerts with them. Do you recall the rehearsals?

A: Yes. I wanted it to be done right and I wanted them ready to go for tour. I knew it could work on stage. I never thought ‘How is this gonna work live?’ When we rehearsed everyone was very cooperative.

Q: You were watching the song leaving the studio.

A: Yes. When the boys were touring in 1966 that was when I first started writing even more parts for them. I can’t answer anything else about it.

Q: You subsequently flew to Michigan that year to see “Good Vibrations” played live for the first time. What was that like?

A: Right. In front of an audience. I just remember saying, ‘That’s fantastic.’ Ten minute ovation. What was it like? I was proud as hell. I took a bow. I knew the group could perform the material on stage. When it went to number one it did give me some confidence I could write in sections.

The songs kept sticking with me. The vocals. I knew they would be heard one day. I don’t think about where I was when I wrote them. I mean, when I heard it for the first time off the shelf, I had forgotten a lot of it. I did not write it for any specific one of guys. I wrote it for myself.

Motown records were an influence on my bass playing. I learned from Motown. I learned how to play bass from Motown for Christ sakes!

Yeah, but I learned how to play different type of roots on certain chords. I love Stevie Wonder. We did his ‘I Was Made To Love Her.” I kind of like that song.

Q: What about the implementation of strings in your work, from “Pet Sounds” to “SMiLE.”

A: I liked Jack Nitzsche’s string arrangements with Phil Spector. Sid Sharp was the guy I called for violins for my sessions. I like strings. It’s good to use strings. Strings bring you in more. Like Nelson Riddle and Frank Sinatra. But you need some spaces and holes. I like horns, too. Brass. I liked to use two saxes, baritones, and a trumpet.

Q: I used to see you around town at Gold Star, United Western, and even Sunset Sound when I was a kid. I know your early albums for Capitol Records were done at studios there. But I never believed that you split the scene from doing the Beach Boys albums from Capitol to other studios because you wanted to be away from under the watch of the record label located in the same building.

A: I didn’t like recording there and not because it was too close to the label. I liked the Capitol rooms, and I liked the instrumental sound, but I didn’t like the vocal sound. I didn’t like that kind of echo chamber. Tell me I’m an idiot! I just didn’t like the vocal sound, so we switched over to Western, and Gold Star. Western had a big room, and Phil Spector was over at Gold Star. Smile started at Gold Star.

Let me tell you a story. I went to Gold Star and asked Larry Levine, the engineer, “What is the secret of the Phil Spector echo trip?” “Well, we have two echo chambers under the parking lot. Phil uses both the chambers at the same time.” So, I tried that myself and it worked.

Q: Paul McCartney once told me how much he liked the bass lines on Pet Sounds. I know you utilized the bass as a principal instrument. On “Here Today” you conceived the idea of the bass playing an octave higher on the rhythm bed track.

A: Because the bass parts resound better in a studio and you can take three hours to get one line if you really needed it. You could take forever and get a goddamn line, you know?

Q: When did you start utilizing two bass players on the same music track, like on Pet Sounds?

A: I asked Larry Levine what Phil Spector did with his basses and Larry said Phil uses a standup and a Fender both at the same time. And the Fender guy used a pick. So, I tried it out at my session and it worked great! You also get a thicker sound putting the two basses together. I start with drums, bass, guitar and keyboards. Then we overdub the horns and the background voices.

“The man [Phil Spector] is my hero. He gave rock ‘n’ roll just what it needed at the time and obviously influenced us a lot. His productions…they’re so large and emotional…Powerful…the Christmas album is still one of my favorites. We’ve done a lot of Phil’s songs: ‘I Can hear Music,’ ‘Just Once In My Life,’ ‘There’s No Other Like My Baby,’ ‘Chapel Of Love’… I used to go to his sessions and watch him record. I learned a lot…”

In 1977 I interviewed Phil Spector in his Beverly Hill mansion and asked him about Brian Wilson.

“I’ve always been flattered that Brian continues to say nice things about me and keeps recording my songs. Brian is a very sweet guy and a nice human being. I’m glad he’s coming out of his shell. I think he got caught in a trap with ‘Good Vibrations.’ I think he got condemned more than condoned.

“He became a prisoner instead of a poet. He had the plaudits, the accolades, and touched the masses. I know music is a very important thing to him, besides a vocation. It became cluttered the last few years. Your attitude is in the grooves, and it’s a very personal thing. But Brian thrived on competition.

“I remember when ‘Fun, Fun, Fun’ came out. He wasn’t interested in the money, but a top ten record. He wanted to know how the song would do against the Beatles and if (AM radio station) KFWB would play it. But I never saw Brian as a competitor.”

In a November 2023 dinner conversation with bassist Carol Kaye, who was on just about all the Spector Gold Star dates, as well as Ritchie Valens’ “La Bamba,” Chris Montez’s “Let’s Dance” and thousands of other sessions, I asked the 90 year-old icon if she ever met any of the Beatles.

“Paul McCartney called me many years ago when he found out I played on the 'Good Vibrations' sessions. We traded picks."

Daniel Weizmann: It’s only now that it’s over that we’ve really started to understand the power of the little 45 rpm record, the way it fortified pleasure and prosperity in the America nestled between Hiroshima and Saigon. What would those years have been without a stack of small black discs with removable yellow or orange centers? The 45 was a contract guaranteeing joyous connection. Two songs, for pocket change, first heard on your car radio or your transistor. It was all the ID card you needed; it proved you were a citizen, proved that you pledged allegiance to the new age. But the 45 presented a Zen koan, too, because it was humble in its way—two lousy, three-minute tunes!—and yet, in the hands of visionaries like Spector and Wilson, the 45 could be a Trojan Horse that snuck into the square world and unleashed a whole army of energies that literally changed everything.”

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015's Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016's Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017's 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble. Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His book Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll TV Scenes) is scheduled for 2025 publication. Harvey wrote the liner notes to CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival. During 2006 Kubernik spoke at the special hearings by The Library of Congress in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 he appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in their Distinguished Speakers Series).

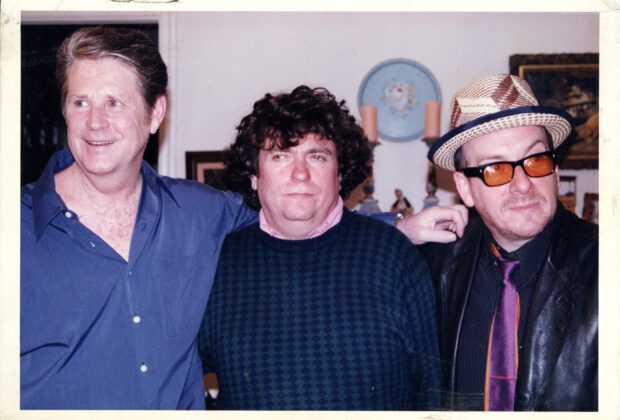

Brian Wilson and David Leaf Photo by Vicki, copyright 2019 David Leaf Productions, Inc.

Book Cover Courtesy of Omnibus Press.

Brian Wilson, Harvey Kubernik, Elvis Costello 1999 Photo by Maggie Magee, Courtesy of the Harvey Kubernik Archives.