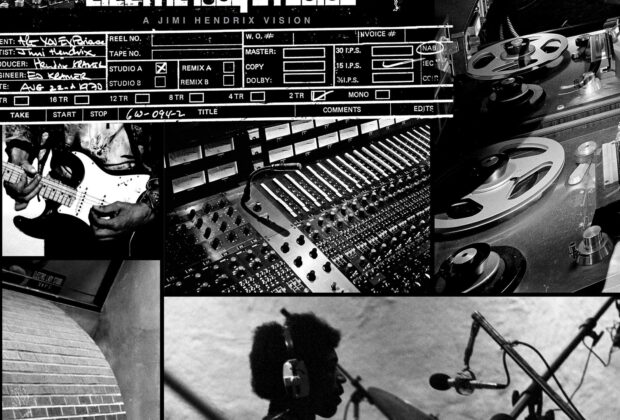

Electric Lady Studios: A Jimi Hendrix Vision Box Set

On October 4, Experience Hendrix L.L.C., in partnership with Legacy Recordings, the catalog division of Sony Music Entertainment, is issuing Electric Lady Studios: A Jimi Hendrix Vision, a deluxe box set offering 39 tracks (38 previously unreleased) that were recorded by the new-look Jimi Hendrix Experience (Billy Cox on bass, Mitch Mitchell on drums) at Electric Lady Studios between June and August of 1970, just before the legendary musician’s untimely death the following month.

The Experience Hendrix L.L.C./Legacy news release describes a Hendrix August 8th event and Electric Lady Studios: A Jimi Hendrix Vision.

“In celebration of the forthcoming release, on August 8, the City of New York will be temporarily renaming the portion of West 8th Street between 6th Street and MacDougal Street JIMI HENDRIX WAY. This is the block on which Electric Lady Studios was built and still stands. There will also be a media screening event inside the studio that night. The official theatrical premiere of Electric Lady Studios: A Jimi Hendrix Vision will be on August 9 at Quad Cinema in Manhattan at 7:00 PM and feature a post-screening Q&A session with director and co-producer John McDermott, co-producer and president/CEO of Experience Hendrix, L.L.C. Janie Hendrix, and producer/engineer Eddie Kramer. The film is distributed by Abramorama and all confirmed worldwide theatrical bookings for it can be found here: https://ajimihendrixvision.com/showtimes/

“The project also includes 20 newly created 5.1 surround sound mixes of the entire First Rays Of The New Rising Sun album plus three bonus tracks [“Valleys Of Neptune,” “Pali Gap,” and “Lover Man”]. The Blu-ray includes the critically acclaimed, full-length documentary Electric Lady Studios: A Jimi Hendrix Vision. The film chronicles the creation of the studio, rising from the rubble of a bankrupt Manhattan nightclub to becoming a state-of-the-art recording facility inspired by Hendrix’s desire for a permanent studio.

“Directed by John McDermott and produced by Janie Hendrix, George Scott and McDermott, the film features exclusive interviews with Steve Winwood (who joined Hendrix on the first night of recording at the new studio), Experience bassist Billy Cox and original Electric Lady staff members who helped Hendrix realize his dream. The documentary includes never-before-seen footage and photos as well as track breakdowns of Hendrix classics such as “Freedom,” Angel” and “Dolly Dagger” by recording engineer Eddie Kramer. The package includes an extensive booklet filled with unpublished photos, Hendrix’s handwritten song drafts, and comprehensive liner notes. The new release comes on the heels of another feature-length documentary that was created by the same team; Music, Money, Madness… Jimi Hendrix Live In Maui, which was nominated for a GRAMMY in the Best Music Film category in 2022.

“Leading the project is a previously unreleased version of “Angel [Take 7].” This newly mixed, stripped down version includes the original performances recorded by Hendrix, Mitchell and Cox on July 23, 1970. It does not include any of the drums and additional percussion elements Mitchell opted to add to this master take after Jimi had died.

“Contained on the five vinyl LPs or three CDs in the Electric Lady Studios: A Jimi Hendrix Vision box set are 39 tracks recorded by Jimi and his band—consisting of bassist Billy Cox and drummer Mitch Mitchell—at the studio within the last four months of the guitarist’s life. Hendrix was hard at work creating First Rays Of The New Rising Sun, the ambitious double album that would follow his 1968 masterwork Electric Ladyland. Inspired by the possibilities of the new studio, the Experience built classic fare such as “Night Bird Flying,” “Freedom,” and “Dolly Dagger” from the ground up. The set offers a comprehensive look at the work Hendrix undertook during that fruitful summer of 1970.

“The music ranges from four-track demo recordings of “Valleys Of Neptune” and “Heaven Has No Sorrow,” alternate arrangements of promising new songs such as “Come Down Hard On Me” and “Belly Button Window,” extraordinary, live in the studio takes of “Tune X/In From The Storm,” “Astro Man” and “The Long Medley,” a stirring, 26 minute spontaneous exploration of “Beginnings,” “Hey Baby (New Rising Sun),” “Keep On Groovin’” and “Freedom.” The box set presents many of the mixes the guitarist completed with engineer Eddie Kramer before leaving to begin a European tour on August 30 at the Isle Of Wight festival in England. Hendrix would never again return to Electric Lady Studios.

“The newly mixed 5.1 audio tracks contained on the Blu-ray of Electric Lady Studios: A Jimi Hendrix Vision include all 17 tracks from the posthumously released First Rays of the New Rising Sun (1997, recorded 1968-70), as well as “Pali Gap” from Rainbow Bridge (1971, recorded 1970), “Lover Man” from The Jimi Hendrix Experience box set, (2000, recorded 1970) and “Valleys of Neptune” from Valleys of Neptune (2010, recorded 1969-70).

“My brother had a musical vision,” Janie Hendrix reflects. “With this project, it felt appropriate to shed light not only on his own music, but also on his lasting contribution of Electric Lady Studios. He was driven internally to build a home base where he could record everything he felt. While his life was cut short, so many other talented artists continue to express themselves within those magical walls on 52 West 8th Street.”

“Jimi’s creative mind was always filled with next level ideas. He was never content with the ordinary but was driven by the burning desire to create something incredible that hadn’t been done before. That was the catalyst for Electric Lady Studios. The film, Electric Lady Studios: A Jimi Hendrix Vision, brings to light just how forward-thinking and inventive Jimi was in every aspect of his music, including production and recording. It was at Electric Lady Studios where he pushed beyond the musical limits of what was known, and he then opened the door to other musicians, allowing them the space to realize their own artistic hopes and dreams.

“My brother conceived something so amazing and so big that it has lived on for decades since its inception, serving as a passageway for hundreds of artists to bring their creativity to a waiting world audience. This is what Jimi envisioned when he founded the New York brainchild, and his prophecy is fulfilled through the countless, brilliant musicians who have tapped into the energy of the studio Jimi created. Legendary artists such as Stevie Wonder, John Lennon, David Bowie, U2, Prince, Jon Batiste, Lana Del Rey, Beyoncé, Jay-Z, and so many others have produced their finest work in the inspired recording house. This film tells the story of how the dream of a visionary, who dared to think outside the musical box, can have a limitless reach, generation after generation. It tells Jimi’s story with his Electric Lady.”

On August 26, 1970 Jimi Hendrix hosted the grand opening of his studio to friends and musicians. At the party were Stevie Winwood, Eric Clapton, Ron Wood and Patti Smith.

During August 27, 1970 Hendrix cut his last studio recording, an instrumental titled “Slow Blues.” He then left with Billy Cox on an Air India flight to fly to London to join Mitch Mitchell for their headlining slot at the Isle of Wight.

James Cushing (Poet and Deejay): Jimi’sIOW set list begins with an unusual three-song medley of “God Save the Queen,” the “Sgt. Pepper” theme, and then into “Spanish Castle Magic.” He continues by introducing a song “written in 1847 but still has something”: “All Along the Watchtower.” Several songs would be unknown to any August 1970 audience — “Freedom,” “Dolly Dagger,” “Ezy Ryder,” “In From the Storm” — but he presents them confidently, without preamble.

During “Red House” Jimi plays without a pick on a Gibson Flying-V instead of the usual Fender Stratocaster. The performance feels “pure” in the sense of being unobserved — no self-consciousness is evident in his face or body.

Was Jimi satisfied with the venue, or his performance? His spoken intro to “God Save” ends, “Stand up for your country and start singing! And if you don’t, fuck you.” And his last words to the assembled: “One of these days we’ll get it together. Peace, love, and all that other good shit.” And he tosses his Strat onto the stage floor. Was he dissing the notoriously disorganized festival? Was he complaining about having to travel all the way from New York to England to play concerts when he most wanted to hole up in Electric Lady Studios, recording away?

My theory: he was building a protective verbal wall around his performance, asserting his independence from the judgment of an audience, emphasizing the unity of the trio’s sound and the clarity of his compositions against the chaos of the surroundings.

On September 18, 1970, ‘the absolute collided with the contingent,’ as John Ashbery said about the death of Frank O’Hara.

Jimi was working on First Rays of the New Rising Sun, the intended title for the double album Hendrix had been working on for many months in his New York studio, a sequel to Electric Ladyland that would consolidate its reach with the jazz directness of Band of Gypsys. The project was left forever incomplete. In fragmented form, it appeared in 1971 as a pair of single LPs, The Cry of Love and Rainbow Bridge.

Eddie Kramer: Jimi never ceased to amaze me with his choice of other peoples’ songs, and his re-interpretation of them. There’s the obvious thing like Bob Dylan. But everything he turned his hand to had this amazing other-worldly kind of sound and performance to it. And re-interpreting other people’s material was one of his great assets. Witness the fact that he loved Dylan, and “All Along the Watch Tower” became his in the sense that even Dylan adopted that performance. It’s Jimi’s thing.”

Dave Mason guests on “All Along the Watchtower.” Hendrix and Mason, then in Traffic, heard Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding at a girlfriend’s apartment, Kathi Etchingham.

Dave Mason: After hearing an advance copy of John Wesley Harding LP, we went over to Olympic studio for a session there. A couple of other people were present, two of the guys in the Pretty Things. I played acoustic guitar with Jimi on the recording session of ‘All Along the Watchtower’ and then there were three or four tracks with him where I played bass and sitar. I also added background vocals on “Crosstown Traffic.”

We worked at Olympic. At the time they weren’t that many studios for one thing. And it was a great room. It was a huge studio that had a large room to record in. Traffic recorded there with Jimmy Miller producing. It’s an easy song and cool lyrics. It lends itself to interpretation. 3 chords. That’s all it is. I later did my version of it because it was a great vehicle to play guitar.

And then there was a point when I wasn’t with Traffic and there was a time when Jimi wasn’t working with Noel Redding. Jimi and I talked seriously about me taking Noel Redding’s place on bass. I believe Mike Jeffrey of his management put a stop to it.”

During 1967-1970, Hendrix recorded four Bob Dylan compositions: “Can You Please Crawl Out Your

Window?,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Tears of Rage,” and “Drifter’s Escape.”

Three different unheard takes of “Drifter’s Escape” are on Electric Lady Studios: A Jimi Hendrix Vision.

Dr. James Cushing: As far as Dylan’s lyrical influence on Hendrix, it might have begun with the song ‘Foxy Lady” and the reference to ‘precious time,’ owing to “Don’t Think Twice Its All Right.”

I always liked Jimi’s lyrics and his singing. The oft handiness of it the little asides I like the way he really internalized the Dylan influence without having it dominate him.

Hendrix and Dylan born in the early forties are two examples of people who grew up without television which might have informed their wild imagination. These men in terms of originality I think they are the two individuals who stand out more than anyone else from the entire rock generation, including Elvis Presley.

Dylan and Hendrix together justify the entire existence of rock. Because with Dylan you have a genuine poetic sensibility that enters the music and flourishes, and with Hendrix you have a genuinely original take of the blues. In terms of timbre, in terms of rhythm, harmony and the fact that Dylan’s journey continues and the fact that Hendrix’s journey was hideously cut off at age 27.

When Jimi Hendrix does a Bob Dylan song, for example, “Like a Rolling Stone,” we have one genius occupying a space created by another. And when that happens, sparks always fly because genius is always unique and so you have two unique things and they aren’t supposed to fit perfectly. So, the Dylan songs become less verbally impressive and more sonically rich.

Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited was important to Jimi and in his record collection and in the African-American community.

There is a famous photo of Huey P. Newton who co-founded the Black Panther Party with Bobby Seale, holding it with the album playing on a turntable and listening to it over and over again.

“All Along the Watchtower,” a lot of people, including myself don’t listen to the words anymore. And the Dylan version foregrounds the words. And the magic of the Dylan version lies in what you discover about the words as you listen to it. Whereas the magic of the Hendrix version consists of the layers and layers of sounds and the different kinds of guitar playing. And in the audio document you get a survey of the possibility of the guitar in three minutes and fifty seconds. The whole thing is so beautifully put together.

It’s a totally coherent work of art. He completely respects the original while completely making it his own. The improvisational bits all fit into a composed way. Dylan is more intimate whereas Hendrix created it more as a kind of psychedelic radio theater of the mind to create this space. I could certainly understand the guitars as elements of an emotional theater.”

Steven Van Zandt (Musician and Deejay): I play a lot of Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde on my Outlaw Country Sirius XM radio channel. I’ve programmed Rod Stewart and the Faces covering “The Wicked Messenger” from John Wesley Harding and Jimi Hendrix doing “All Along the Watchtower.”

Jimi Hendrix did more to promote John Wesley Harding than anybody. It was one of the most remarkable records ever made of course. And the fact that Jimi picked up on that from that unusual, but not very popular Bob Dylan album, and made everybody go back to it. And, I’m telling you, that’s how powerful that record was. Everybody went back to John Wesley Harding after hearing Hendrix thinking “you know, maybe I missed something? Look what Jimi Hendrix did with it. Look what the Faces did with it.” It’s a terrific album but sort of subtle, compared to Blonde On Blonde that most people consider Bob’s peak.

Daniel Weizmann: (Writer and Music Historian). On his masterpiece cover of "All Along the Watchtower," Jimi could've taken Dylan's lyrical maze in so many directions. What he does is totally counter-intuitive. Between explosions, he deploys Homeric trance-inducing parataxis--short even phrases to mount tension. The effect is apocalyptic.

That Jimi copped Bob’s hair doesn’t surprise me. Because I think Jimi identified with Dylan on a very deep level and, in some spiritual way, was even trying to do with electric sound what Dylan did with lyrics. Though their art is different on the surface, they share an almost supernatural ability to take sudden sharp left turns, to mix the mythological and the everyday, and to catch you off guard with the casual way they toss out gems that a lesser artist would hoard. The hair says it all.

I think Jimi's voice is a cornerstone of his art, a savvy and unusual approach. He brings an attitude, a cadence, and a tone that helps frame and even beautify the greatest electric guitar playing ever recorded.

To understand the vocal choices Jimi made, you first have to dig what he chose not to do. For a guy who poked at every last corner of the blues and bent the whole genre to his will, Jimi rarely wailed, growled, or went for "long yardage" and high emotion like so many bluesmen o the day, black or white. In the rock world, where he was frequently the sole African-American onstage, he never did traditional "Soul with a capital S" and he didn't even "rock" vocally the way, say, a Robert Plant or an Iron Butterfly might be known to rock--to throw their guts into the notes.

No. Jimi was cool, plaintiff, just this side of conversational. Even as his guitar tore off the chain like a Tasmanian Devil, he himself never overheated. With great restraint and sagacity, he made it a point to step out of his own way. In storyteller's parlance, Jimi plays human-sized narrator, and lets the guitar handle the force of antagonism--the thunder and the lightning, the dragon's breath and intergalactic flight.

On the best jams--especially live stuff like "Foxy Lady" at Miami Pop, "Hear My Train a Comin'" at Fillmore East, so many!--there's an almost Rabbinic incantation to his voice, simple but mesmerizing. He simply refuses to gild the melody's lily--no mean feat for a guy who knows from musical elaboration.

“TS Eliot famously said that “Poetry is not a turning loose of emotion, but an escape from emotion; it is not the expression of personality, but an escape from personality.”

By 1974, Dylan demonstrated the ultimate show of respect when he began using Hendrix’s template to perform “All Along the Watchtower.” On a February 9, 1974 tour stop at the Seattle Center Coliseum with The Band, Dylan in a rare stage comment proclaimed, “great to be in Seattle, birthplace of Jimi Hendrix!”

In a 2012 I conducted an interview with Janie Hendrix who provided an insight into the Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix mutual admiration society.

“Jimi really loved the lyrics of Bob Dylan. And he was one person who I met who really admired Jimi.

“Years after Jimi died my dad got a phone call. I had come home from college and he said, “You’ll never believe who called today.” “Who?” “Bob Zimmerman. Bob Dylan.” I did the same thing. “What did he want?”

“Well, he called, and said, ‘first of all, I want to give you my condolences for Jimi passing. And I know you’ll find this odd that its ten years later and I’m finally calling but I’ve picked up the phone so many times in the last decade and I just couldn’t bring myself to call you and talk to you. But Jimi was more than somebody that admired my music. I admired him. He was a friend. And it just hurt, extremely when he died. And just wanted to pick up the phone to call you and give my condolences.’

“Wow…Of course my dad was very emotional and it made him cry. “Why thank you for calling.” And Dylan said, ‘the next time I am in Seattle I’d like you to come to the concert.’ ‘OK.’

“So, a few years later, Bob Dylan came to town and he invited us to the show and we went backstage. And, here is my dad, late seventies, and a little camera on his wrist and he’s got arthritis and not walking very well. But we get backstage at The Paramount in the green room. And he’s reaching for his camera, and Bob Dylan doesn’t like to take pictures, so his body guards almost attack my dad (laughs).

“I’m sorry. I would like to have a picture with you.” And Bob Dylan had on his slip up hoodie and pulled the hood off and said, ‘It’s OK. Come on.’ So, I took some pictures of them. I mentioned ‘Jimi always said he loved your lyrics.’ And he said, ‘I loved his guitar playing.’

“At the concert we also had been given seats and chairs at the side of the stage and the guitar player nods at me and I nudged my dad as they were getting ready to play “All Along the Watch Tower.” And Bob Dylan made it a point to say, ‘I do it the way Jimi did it to honor Jimi. Even though it was a song I wrote.’

Eddie Kramer: I was very fortunate to work with James Marshall Hendrix I find when I do interviews, I thank God I was able to work with a man like that, because he changed my life and many other peoples’ lives. He was the greatest.

I think it’s the purity, the fact that there this amazing dynamic all rolled up into one human being. There is the amazing presence. I can just say that whenever Jimi walked into a room you had to turn your head. Because you felt you were in the presence of something quite unusual. And he had this way of commanding attention without commanding attention. His demeanor or was so shy and self-effacing. He just sat there in a corner but people were attracted to him. It’s like magnetism. You have that aspect, which is the shy, wonderful soft spoken human being who at the turn of a switch as soon as he got on stage became this otherworldly being who could unleash gobs of power and lighting bolts at you. I think that’s one aspect.

Then you dive into all the other aspects, which, of course is, the music. This synergy or synthesis if you will of all of the bits and pieces of information that had flooded his brain.

Whether it’s blues, rock, pop, R&B, classical and the sound of dropping out of an airplane when he did his parachuting.

I think it’s that auditory sponge-like brain that would take everything in with no filtering and probably would sit there for a day or two or three or a month or a year whatever, and out of it would come in the form of a song. And it’s a unique thing

When you look back at how he first started to write songs, with Chas Chandler’s encouragement, and he absorbed so much. And, the surprising thing is that the music is so pure and so flamboyant and descriptive it conjures up imagery which I feel very few rock artists have come close too. And the passion and the emotion and the bareness of it.

Listen to “Voodoo Child” for God’s sake.

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015's Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016's Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017's 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters.

He is writing Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll Television Moments).

Kubernik is in several book anthologies, most notably, The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey wrote the liner notes to CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

During 2006 Harvey spoke at the special hearings initiated by The Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 Kubernik appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in their Distinguished Speakers Series, and in 2024 at The Grammy Museum.