I first met Brian Wilson in early 1962 at a record shop in Culver City when the Beach Boys were doing an in store appearance to promote their record “Surfin’” on the Candix label.

In 1965 I talked to Brian and his wife Marilyn at a hamburger restaurant at Town and Country in the Fairfax district.

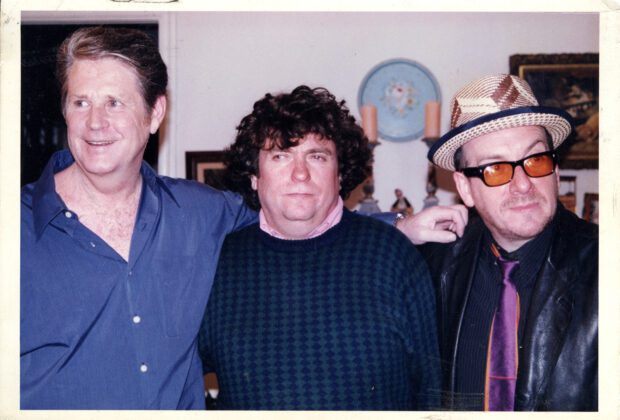

I worked with Brian on a few projects over the decades. Since 1974 I've conducted many interviews with him and wrote the 2007 program for Brian Wilson's Pet Sounds tour. He supplied the lone testimonial for my first book This Is Rebel Music in 2004.

Until this decade, every time I published a book, he would hear about it from mutual friends and somehow get on the phone and congratulate me.

In 2007 in a chat, he asked me what was my favorite Beach Boys album. I said, Beach Boys Today. He was silent. He was expecting Pet Sounds, and I tossed a Sandy Koufax-like fast ball, and he caught it. I then met him for breakfast at our local delicatessen, and had him autograph a CD.

My brother Kenneth and I wrote the text and helped assemble the debut coffee table photography book of Guy Webster, Big Shots. Brian penned the book introduction.

It was in 1965 at RCA studios in Hollywood where Brian met Andrew Loog Oldham, who was producing a session on the Rolling Stones at Studio A with engineer Dave Hassinger. In 2000, Andrew told me that Brian said to him that one day he would "write songs that people pray to."

During 2007 I told Brian what Andrew mentioned. Brian put down his fork after we devoured slices of carrot cake, and replied, "Yes I did. I don't remember when I first felt that. I know music was more than people applauding and buying records. Even when Pet Sounds came out a lot of people told me it got them through high school or college. The most amazing comment I got from one guy who said ‘that’s the most spiritual album I’ve ever heard.’" Brian: The mission continues.

Brian Wilson and Harvey Kubernik 2007 and 2014 interviews.

Q: You have always told me the Four Freshmen were a big vocal influence on you.

A: I was 14 years old. It was at the Coconut Grove (at the Ambassador Hotel) in Los Angeles, and I was shaking. I was so scared to meet the Four Freshmen after seeing the show. And my dad said, ‘Hi. I’m Murry Wilson. This is my son Brian.’ I was so afraid. I was a big time fan and shaking so hard I could hardly talk. It was my first live music. They could reproduce their album sound on stage. Absolutely. The high singer, Bob Flanagan, came to our Hawthorne landmark event a few years ago.

Q: Do you remember the first day you went into Capitol Records in 1962?

A: Yes. I remember walking into the building with my father and Gary Usher. We met the A&R man, Nik Venet. And he listened to our demos and he signed us right on the spot. We played him “409” and “Surfin’ Safari.” “I want to sign you guys right now.” I just wanted to make records. I didn’t know how big it would get. I didn’t think it would.

Q: Let’s discuss a lot of your songs in the Beach Boys’ catalogue. ‘‘All Summer Long.”

A: That was inspired by my (former) wife Marilyn when I spilled coke all over her at the Pandora’s Box club in Hollywood.

Q: “Catch A Wave.”

A: Was my attempt to create a group style that mixed falsetto, mid-range and bass and backup singers all at once.

Q: “Hawaii.”

A: I was in Hawaii when I wrote it on a piano.

Q: “409.”

A: My buddy Gary Usher had a red 409. After we wrote the song and recorded it, we took a tape recorder and he revved up his 409 and we took the tape to the studio and overdubbed it on the record. How ‘bout that for a story?

Q: Gary is overlooked in music history. He later produced some Byrds’ albums.

A: Gary is an underrated producer.

Q: I also enjoyed the songwriting ability of Roger Christian. He co-wrote “Don’t Worry Baby” with you. Roger was a radio deejay at KFWB in Hollywood.

A: As well as “Car Crazy Cutie” and “Little Deuce Coup.” He gave me the lyrics and I put music to them. I wrote “Surf City” with Jan Berry.

Q: Yes. You used to meet Roger after his radio shift at KFWB at C.C. Brown’s Ice Cream Shop on Hollywood Blvd.

Q: “Please Let Me Wonder.” The stereo mix makes it a bit more cinematic since the song is about opportunity and destination.

A: That was cut at 4:30 in the morning. I went to the studio in the middle of the night. I called my engineer, Chuck Britz, at Western, so my wife and I went to the studio. We were there 5-8 a.m. One of my favorite recording sessions I ever had in my life.

Q: “Let Him Run Wild.” I know you never liked your super high lead vocal on it. Brian, the energy of hesitation and the warning track tempos are totally captured on your instrumental production.

A: I was just a little too effeminate on it. If I played it right at this moment with my wife or friends are around I just push the stop button.

Q: In late 1965 at RCA studios in Hollywood you first met Andrew Loog Oldham when he was producing a session with the Rolling Stones. On that day you told Andrew that “you would one day write songs that people would pray to.”

A: Yes I did.

Q: I think “This Whole World” has a spiritual aspect to it. I played “This Whole World” on headphones recently. It really helped me remove toxic people from my orbit and further appreciate life on earth. You even mention gospel in the lyric. There’s also an ARP synthesizer and all sorts of bitchin’ production going down with engineer Stephen Desper. But, Brian, the recording is only two minutes and twenty seconds! It has to be played twice on my cassette tape. Then I hear more things in the mix!

A: Harvey, a song is never finished…I think my music has helped people a little bit. I think it is therapy for people. Music therapy. I think Marvin Gaye’s music is very therapeutic. I think Diana Ross’ music is very therapeutic, to name just a couple.

Q: But it’s therapeutic for you, too.

A: Very much so.

Q: I used to see you around town at Gold Star Recording Studio, United Western, and even Sunset Sound when I was a kid. I know your early albums for Capitol Records were done at the Capitol studios on the premises. But I never believed that you split the scene from doing the Beach Boys albums from Capitol to other studios because you wanted to be away from under the watch of the record label located in the same building. Was there a reason?

A: I didn’t like recording there and not because it was too close to the label. I liked the Capitol rooms, and I liked the instrumental sound, but I didn’t like the vocal sound. I didn’t like that kind of echo chamber. Tell me I’m an idiot! I just didn’t like the vocal sound, so we switched over to Western, and Gold Star. Western had a big room, and Phil Spector was over at Gold Star.

Q: How did the creative atmosphere in Los Angeles shift from the 1950s to the 1960s and beyond? Was the shift a result of the place (Los Angeles) or a result of the new generation of performers and artists emerging from and performing in Los Angeles?

A: The creative shift had something to do with the new recording studios that were built in the very early sixties and how good the studios were in the fifties. I didn’t like recording at Capitol during 1962-1964 and not because it was too close to the label. I liked the Capitol rooms, and I liked the instrumental sound, but I didn’t like the vocal sound. I didn’t like that kind of echo chamber. I just didn’t like the vocal sound, so we switched over to Western, and Gold Star. Western had a big room, and Phil Spector was over at Gold Star. I felt comfortable at Western Recorders, Western Recording on Sunset Boulevard. I loved the board at Western. A really good board. And my engineer, Chuck Britz was really good. Chuck was really good for using echo and he was great combining guitars and pianos together. He was really good at that kind of thing. I actually was very at home at Capitol earlier, I liked it a lot. Plus, I liked working at Sunset Sound. They had a good tack piano there.

Q: You were recording on a four-track tape machine in 1965 and ’66, and then Columbia Studio on Sunset Blvd. was the first place where you really got into 8-track recording. What was it like recording on 4-track and then moving to an 8-track machine?

A: Well, we recorded the background tracks at Western. And then we went over to CBS for the vocals on 8-track. I felt confined with 4 tracks. 8 track was fantastic. You could put the cello on one thing and the Theremin on another. It was fantastic. I was also able to record tracks at Gold Star, Western, Sunset Sound, CBS--- and bring the tapes to each studio. It’s a whole different trip because it’s the same song but you’re going to a different studio. Truth is, going to different studios didn’t really matter. All that matters is the vocals, because I tried to do vocals first and then the music. I didn’t like to do that a lot. It was tracks first because you had to have something to sing too.

Q: How about working with engineers like Chuck Britz at Western, Stan Ross, Dave Gold, Larry Levine and Doc Siegel at Gold Star. Then, Bruce Botnick at Sunset Sound, along with several engineers at Columbia, including Ralph Balantin and a session for “Vege-Tables” with Armin Steiner at his studio.

A: The best trip is that they know music. They are good at music and engineering, too. People like Chuck Britz made suggestions. ‘How ‘bout if we had a little more pick on the bass?’ ‘How ‘bout if the piano had more of a tacky sound.’ Chuck Britz was like a co-producer but only got credits for being an engineer.

Q: In what ways does the music and culture from Los Angeles in the ‘60s and ‘70s continue to influence music, film, and popular culture? How wide reaching and significance are these influences today?

A: We first did the songs, the records in the studio. As singles and then as albums. Then they end up in TV and film soundtracks. It’s a thrill and a good experience. Why does it keep going? The influences. Mainly because the harmonies. That’s really our key to our success was our harmony. People working together. That kind of vibe.

Q: Given these ongoing reverberations and influences, do you think this was among the most significant creative periods in modern popular culture history?

A: It goes back earlier. The fifties. KFWB radio. I learned about Chuck Berry in the mid and late fifties. And it helped me learn how to write rock and roll songs.

Q: “You’re So Good To Me.”

A: I wanted to try something at the piano, working the keys on the piano, and don’t know how I formulated the damn song. But I stretched the vocal and inspired myself. I always write on piano, Harvey. It gives me chords. Chords and rhythm and the piano translates.

Q: “Then I Kissed Her.”

A: It’s in the show. The opening riff is my favorite riff ever written. And on the record I wanted to feature Al and give him a chance to stand up and sing. It’s hard to describe Al’s vocals, but he can go up there and get pretty high.

Q: On the original Crystals recording, that’s Barney Kessel playing the opening riff on a Rickenbacker 12-string guitar.

A: Barney Kessel! I’ll be damned.

Let me tell you a story. I went to Gold Star and asked Larry Levine, the engineer, “What is the secret of the Phil Spector echo trip?” “Well, we have two echo chambers under the parking lot. Phil uses both the chambers at the same time.” So, I tried that myself and it worked.

Q: Paul McCartney told me how much he liked the bass lines on Pet Sounds. I know you utilized the bass as a principal instrument. Like on “Here Today” you conceived the idea of the bass playing an octave higher on the rhythm bed track.

A: Because the bass parts resound better in a studio and you can take three hours to get one line if you really needed it. You could take forever and get a goddamn line, you know?

Q: And around 1969, 1970, ’71, you also utilized drummer and percussionist Dennis Dragon.

A: Yes. I gave him a couple of drum jobs.

Q: Actually, you gave him three gigs.

A: Name them!

Q: “Disney Girls (1957),” the drum solo on “Suzie Cincinnati” and “It’s About Time.” He’s the percussionist and Earl Palmer is the drummer on the session.

A: Right. Exactly! How do you know that?

Q: Dude, you’re talking to Harvey. I don’t need to go on the internet like Wikipedia children. I knew Dennis. He told me.

A: This is deep trivia for me! And Earl Palmer played on some Spector stuff. I know “You’ve Lost That Loving Feelin’” was Hal Blaine. Hal played on most of my records and Earl on one of them.

Q: On Surf's Up I love ‘“Til I Die.” Where the heck did that come from? Deep in the groove count like Don Drysdale hurling a fastball pitch. I think it’s your most vulnerable lead vocal ever recorded.

A: Well, I put a b note in g major 7th chord and it was a 3rd in the chord, and the note in the key of g resonates pretty well. Lyrically, I tried to put nature in there. Earth, water, rocks and leaves.

Q: I like “Forever.”

A: Oh God. Well, I helped Dennis (Wilson) with the arrangement and he wrote the song. A tearjerker…Dennis is an underrated music person.

Q: “Surf’s Up.”

A: Van Dyke and I wrote that at my house. It was about 11:00 in the morning, and we had a sand box with a piano in it and it took us 30 minutes to write it. Maybe an hour and a half. We just wrote it really spontaneously. We title songs after the lyrics. I never wrote a song on guitar or bass. We were trying to get across the feeling of children. How much their love means to people. Van Dyke Parks is the greatest lyricist I’ve ever heard. His lyric writing is poetic.

“Leonard Bernstein had me play ‘Surf’s Up” on TV. He told someone he liked it. A song has to work on the piano before it goes to the studio. On the keyboard you can see what you’re writing. You can hear and see it.

Q: “Feels Flows.”

A: That was Carl singing. Charles Lloyd is on it.

Q: “Sail On Sailor.” Carl produced the recording and Blondie Chaplin’s vocal performance is stellar. I know Van Dyke Parks lobbied for the song originally to be recorded.

A: I was at Danny Hutton’s one time. Tandyn Almer and I wrote a song, “Sail On Sailor” it on a Wurlitzer electric piano and Ray Kennedy was there and started writing some lyrics. “Ray, I didn’t know you could write lyrics.” “Keep playing! Keep Playing!” We wrote the thing in about an hour and a half or two hours. Later, Van Dyke Parks tweaked it a little bit. (Jack Rieley added some lyric revision as well).

Q: “Don’t Go Near The Water.”

A: Totally Alan’s trip. I was not part of that. Same with “California Saga.”

Q: In 1971 I saw the Beach Boys one night with Flame opening, and the next night the Bee Gees at the same venue, the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium.

A: The reason I love the Bee Gees is because of their harmonies.

Q: Barney Kessel was married to the legendary vocal contractor, B.J. Baker who also sings on “Got To Know The Woman,” a Dennis Wilson song from your Beach Boys’ Sunflower album.

Q; I was amazed when you mentioned that you originally recorded the instrumental Pet Sounds for a James Bond movie, Dr. No.

A: It got turned down, Harvey. They turned it down! They turned the damn thing down. It got submitted. If you can do the twist then “Pet Sounds” got turned down. “We don’t have any interest in that song.” I’m gonna put it on Pet Sounds. That’s why it went on Pet Sounds. The James Bond people turned it down. And, when we play the “Pet Sounds” instrumental on stage now I turn around and face my band and take the piece in.

Q: This reminds me of the days we would sit around play 45RPM records and sing along with them. These days when you and your band perform “God Only Knows,” the song always garners a standing ovation from everyone in the crowd. Why?

A: Because we’ve had a little practice, Harvey. (laughs) Second of all, Carl (Wilson) is gone, and third of all, I have to carry what he used to carry. I have to carry the damn weight. I have to carry the ball. I don’t remember the recording session of it. Too far in the past to remember. I mean, here is your part…O.K. Here is your part…O.K. And, somehow, we got “God Only Knows” done. And, the record spoke for itself. And it was a religious experience. Carl and I were into prayer. We held prayer sessions in our house on Laurel Way. “Dear God. Please let us bring music to people.” It happened. A cool trip. A lot of people say to me that Pet Sounds got them through high school or college.

Q: “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” from Pet Sounds. Barney Kessel’s guitar introduction on the track is just terrific.

A: Barney did the introduction to the song and Glen Campbell was also there. And, I said to myself, “I’m going to have these guys play directly into the board instead of going out into the studio.” And they plugged their instruments into the recording console direct. That’s how we got that sound. I also did that on “California Girls.” My brother Carl played a 12-string on that and we plugged him into the console and he did his thing. Every now and then I’ll do that.

Q: “Caroline, No” is your favorite song on “Pet Sounds” and the prettiest ballad you’ve ever sung. The recording tempo was pushed up a beat.

A: And guess whose idea that was?

Q: Your father Murry Wilson.

A: Yes. He said to speed it up a half a note and you’ll have a real special song. I did it and it worked. What can I say?

Q: “Break Away” is in my top ten Beach Boys’ records. The co-writer on the song is Reggie Dunbar, a pseudonym for your father Murry Wilson, who did write songs himself.

A: My dad and I wrote it. He didn’t want anyone to know that he wrote it with me. Believe it or not, we wrote some of it on my doorstep outside my house and some sitting around at the piano. Sure, I was still friends with my dad after he didn’t work with us anymore. He was a good buddy. It was done at Sunset Sound Recorders, which was just as good as Western.

Q: “Sail On Sailor.” Carl produced the recording and Blondie Chaplin’s vocal performance is stellar. I know Van Dyke Parks lobbied for the song originally to be recorded.

A: I was at Danny Hutton’s one time. Tandyn Almer and I wrote a song, “Sail On Sailor” it on a Wurlitzer electric piano and Ray Kennedy was there and started writing some lyrics. “Ray, I didn’t know you could write lyrics.” “Keep playing! Keep Playing!” We wrote the thing in about an hour and a half or two hours. Later, Van Dyke Parks tweaked it a little bit. (Jack Rieley added some lyric revision as well).

Q: “Cool, Cool Water.”

A: Well there is something special. The recording session was brilliant. Mike was absolutely brilliant. He was right on.

Q: Did the principal guitar lead played through a Leslie speaker on “Marcella” get influenced from George Harrison’s lead guitar part on “Let It Be?”

A: Absolutely. Absolutely. Marcella was a Spanish chick that worked at a local massage parlor.

Q: What about teaming with lyricist Tony Asher for Pet Sounds?

A: A cool kind of guy. A little more soft spoken. His attitude is just right for creativity and just right to work with. I might call him up as a matter of fact. That might be a good bet for me. Just before we began collaborating on Pet Sounds I asked him what it was like writing commercials for an advertising company. It seemed like interesting work. I said, “You should be good with words if you can do that.” And, he said, “I’m pretty good with words.” Out of nowhere I said “Would you like to work with me on some songs and write some lyrics?” “I’ll give it a try.” Then, Pet Sounds, like that. 1966 was a very big year for the Beach Boys.

Q: Can you describe collaborating with Van Dyke Parks?

A: Working with him is not easy at all because he is a perfectionist. So he wants it his way and the right way. So, I go, “Yes, Van Dyke.” He’s say “OK, but that’s not what I had in mind.” “OK.” I never argue about things. I’ve always liked what he’s come up with. That’s the thing. Always. I’d never say that sucked ‘cause that would hurt his feelings. He’s a gentleman and a scholar. A very bright person.

Q: In 1977 you told me “I don’t carry a notebook or use a tape player. I like to tell a story in the songs with as few words as possible. I sort of tend to write what I’ve been through and look inside myself. Some of the songs are messages.”

You’ve written a lot of songs with various co-writers and lyricists and there are songs which are just your words and music. Is the process different from a collaboration. Think of “Surfer Girl,” “The Little Girl I Once Knew,” “Girl Don’t Tell Me,” ”I’m Bugged At My Old Man,” “Passing By,” “Busy Doin’ Nothin’,” “Our Prayer,” “Love & Mercy,” “This Whole World,” and “Til I Die.”

A: I get that feeling when something tells me it’s never gonna end. So, it never ends. What do I do? I go to sleep. A song is never finished…

Q: Do the titles of songs come first?

A: Titles usually come after the lyrics are done.

Q: “The Little Girl I Once Knew.” I know as a teenager Rodney Bingenheimer attended this recording session.

A: Yes, he did. That is my very favorite introduction in a song in my whole life. It kills me every time.

Q: Because of the way the music is suspended on the front end of the track?

A: Yes. Yes. It might have been the first time the music stopped and started again on a record. I wrote the intro at the studio before we cut the thing. And, (session musician) Larry Knechtel, it was his idea to keep the music rolling. And we tried one, and then I put a second guitar overdub on top of the other guitar. And the rest of it was history. We were doing stereo but I could only hear the mono and I always put the vocals up front in the mix. Mixing in mono is good for my left ear. My right ear is broke, done and over with.

Q: I recall years ago during some Capitol Studios mastering sessions you always had to lean close to one speaker during the tape transfer since you had reduced hearing in one ear and would position your head right next to the just one speaker. The engineers were amazed by you discovering some high end and bass frequencies on playback. I really dig the “Wendy” record.

A: It was not written about my daughter Wendy. This was way before she was born. You know it starts with a bass slowed down with a guitar. It was an attempt to flatter the Four Seasons. I wanted to try and imitate the Four Seasons in a way they would like to hear it. ‘Cause I like (producer) Bob Crewe and the way they do their vocals.

Q: “The Warmth of the Sun” is wonderful.

A: Probably Mike Love’s most beautiful lyrics he’s ever written and one of the prettiest songs I ever wrote. I think it’s because JFK had died the day before. We dedicated it to him and I tried to sing it sweetly and angelically, you know, trying to capture the sound of a sweet angel.

Q: Both you and Paul McCartney as songwriters go away from the root chord and establish counterpoint sound. It’s a structure both the Beatles and the Beach Boys did. Talk to me about veering away from the melody away from the root chord as a composer.

A: I learned that from Motown. I learned how to play bass from Motown for Christ sakes! I learned how to play different type of roots on certain chords. I love Stevie Wonder. We did his ‘I Was Made To Love Her.” I kind of like that song.

Q: What was the difference collaborating with Van Dyke Parks on “SMiLE” to lyricist Tony Asher whom you worked with on “Pet Sounds?”

A: Well, Tony Asher worked a little slower working with me than Van Dyke who was faster.

Q: Why did you select Van Dyke Parks? He emailed me in April and said the first time he talked to you was at a party.

A: I met him in 1965. We met initially at a lawn party held by Terry Melcher at his home off Benedict Canyon, overlooking Beverly Hills. Later Van Dyke came up with David Crosby on a visit to check out my new home recording set up. Van Dyke was brilliant at talking. I picked him because he was good with lyrics and pretty good with music, too. I can’t answer what drew me to him.

Q: Were you a fan of Bob Dylan in 1965 and ’66?

A: I liked him. Yeah. We did a song of his on the Beach Boys Party album. I thought Dylan’s voice was an interesting voice. I like him.

Q: Do you remember your first writing sessions with Van Dyke Parks?

A: Initially, he did not want to work on ‘Good Vibrations’ because when he heard it, he thought it was finished.

Q: Do you remember the origin of “Heroes and Villains?’

A: I sure do. The song started at my Laurel Way house. We had a sandbox and a piano. The actual recording took five or six weeks. I love “Heroes and Villains.” The magic of Van Dyke’s lyrics and my lead vocals. It’s a pretty youthful lead.

Q: What was it like writing songs in a sandbox?

A: It made us feel like we were on the beach and gave us a touch of the beach. I took my shoes off. Got me in touch with nature a little bit more. I remember when they poured the sand in the sandbox. It was pretty cool to watch.

Q: Were you aiming for a sound when you began SMiLE?

A: We weren’t going for a sound when SMiLE started. We were going for just music. We didn’t know what it was going to sound like. I don’t remember when I first felt that. I know music was more than people applauding and buying records. Even when ‘Pet Sounds’ came out a lot of people told me it got them through high school or college. The most amazing comment I got from one guy who said ‘that’s the most spiritual album I’ve ever heard.’

Q: What about the implementation of strings in your work, from Pet Sounds to SMiLE.

A: I liked Jack Nitzsche’s string arrangements with Phil Spector. Sid Sharp was the guy I called for violins for my sessions. I like strings. It’s good to use strings. Strings bring you in more. Like Nelson Riddle and Frank Sinatra. But you need some spaces and holes. I like horns, too. Brass. I liked to use two saxes, baritones, and a trumpet.

Q: You brought in the Theremin instrument in “Pet Sounds” for “I Wasn’t Made For These Times” and it is even more prominent in “Good Vibrations” and tracked for “SMiLE.”

I know during Pet Sounds you saw jazz guitarist Barney Kessel at a session at Western recording with a Theremin player for a science fiction soundtrack. You then requested Barney to do a session the very next day and to bring the Theremin guy. Barney said, “I’ll ask him and see if he’s available.”

A: Yes. I first discovered it when I was a little kid. My mom and dad had a friend who had a thing where you put your hand out and get a sound that goes higher and lower. And then I found out about what they call a band Theremin where you slide your finger across a band. And I used it. It is an instrument that you use sparingly.

Q: Do you remember the first time you heard the final mix of “Good Vibrations” in the studio.

A: At the playback, all the guys said, Hey Brian. This is a number one record.’ I said, ‘You know what? I agree. I think this is gonna be a number one record.’

Q: What is the one thing, the specific element in “Good Vibrations” that still resonates with you when you hear the recording?

A: Mike’s bass part was the one. Mike’s voice on it was the thing that sold me on it. Mike’s singing got us famous. Because his voice has a quality to it that goes hand and hand with the song. He was the appropriate singer for the song.

Q: You told me in 2007 the first time you ever heard “Surfin’” on the radio from DJ Wink Martindale on radio KFWB that you had to pull over to the side of the road.

A: I couldn’t believe I was actually on the radio. Could not believe it. And, when I heard “Good Vibrations” on the radio for the first time on the radio I cried my eyes out. I was in my house in Bel-Air when I heard it on the radio. My God!

Q: You told me a few years ago you loved that record because of the magic of Van Dyke’s lyrics and your lead voice on the record.

A: It’s a pretty youthful lead. Because the damn thing is so together and cohesive. It comes together so beautifully that people can’t resist lovin’ it.

Q: I remember when the Beach Boys rehearsed “Good Vibrations” on Sunset Blvd. at the former site of The Moulin Rouge that eventually was known as The Aquarius Theater. Just before the play “HAIR” was in that building. You were teaching the group the intricate vocal parts because you were not going to performing in concerts with them. Do you recall the rehearsals?

A: Yes. I wanted it to be done right and I wanted them ready to go for tour. I knew it could work on stage. I never thought ‘How is this gonna work live?’ When we rehearsed everyone was very cooperative.

Q: You were watching the song leaving the studio.

A: Yes. When the boys were touring in 1966 that was when I first started writing even more parts for them. I can’t answer anything else about it.

Q: You subsequently flew to Michigan to see “Good Vibrations” played live for the first time. What was that like?

A: Right. In front of an audience. I just remember saying, ‘That’s fantastic.’ Ten minute ovation. What was it like? I was proud as hell. I took a bow. I knew the group could perform the material on stage. When it went to number one it did give me some confidence I could write in sections.

Q: I know with you everything is, “what key is it in?” Al Jardine said to me that starting in 1965 you really started thinking, “I’ve got to get these guys leads that they can sing on the road.” Like, Al’s vocal on “Help Me, Rhonda.” Al Jardine is heard all over SMiLE. I want to discuss the other group members as singers.

A: In ‘Good Vibrations,’ Mike’s singing got us famous. Because his voice has a quality to it that goes hand and hand with the song.

“Carl Wilson is my favorite rock ‘n’ roll singer. He had a resonate voice and he had a lot of energy and power in his voice. In which I didn’t have or Mike, or the other guys. Carl and Dennis were both my brothers and my artists.

"Dennis as a singer... First of all, he had an energy. Right? Second of all he had a nice quality about his voice. Coupled energy with a sweetness and that was his whole trip.

"Bruce Johnson. He is not an energy singer. Bruce is a sweeter singer and a better falsetto.

Q: Where did the title “Good Vibrations” come from?

A: From my mother. In Hawthorne, California. She said, dogs bark at humans because they think of good vibrations,” they pick up on bad vibrations but don’t mind picking up good vibrations. My mother got the title for it

Q: Do you like listening to music on compact discs or do you miss vinyl?

A: You know I like CD’s. God yes. I could never tell the difference between the sound on vinyl and CD’s. I don’t like listening to songs on cassette, or DAT. I’m a CD boy. More songs on a CD, too.

(In 1974 Harvey Kubernik wrote the landmark review in The Los Angeles Times Sunday Calendar sectionof the Beach Boys’ Endless Summer double album released by Capitol Records. In 2014, Harvey conducted the interview with Wilson for his book collaboration with Sir Peter Blake, in the limited edition That Lucky Old Sun forGenesis Publications.

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015's Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016's Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017's 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll TV Scenes) is scheduled for 2025 publication.

Kubernik’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown is in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett was published in 2019 by Oxford University Press. Brackett is a Professor of Musicology in the Schulich School of Music at McGill University in Canada.

The New York City Department of Education will publish for 2025 the social studies textbook Hidden Voices: Jewish Americans in United States History. Kubernik’s 1976 profile/interview with concert promoter Bill Graham on the Best Classic Bands website Bill Graham Interview on the Rock ’n’ Roll Revolution, 1976, Best Classic Bands, is included.

Harvey penned liner notes to CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

During 2006 Kubernik spoke at the special hearings by The Library of Congress in Hollywood, California, addressing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 he appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in their Distinguished Speakers Series. Harvey spoke at The Grammy Museum in Los Angeles in 2023 discussing the Martin Scorsese-directed The Last Waltz.

Kubernik has lectured at the University of Southern California School of Cinema-Television about Oscar-winner D. A. Pennebaker, examining his acclaimed documentaries on Bob Dylan, Dont Look Back, and David Bowie, Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, for Dr. David James).

Photo by Maggie McGee