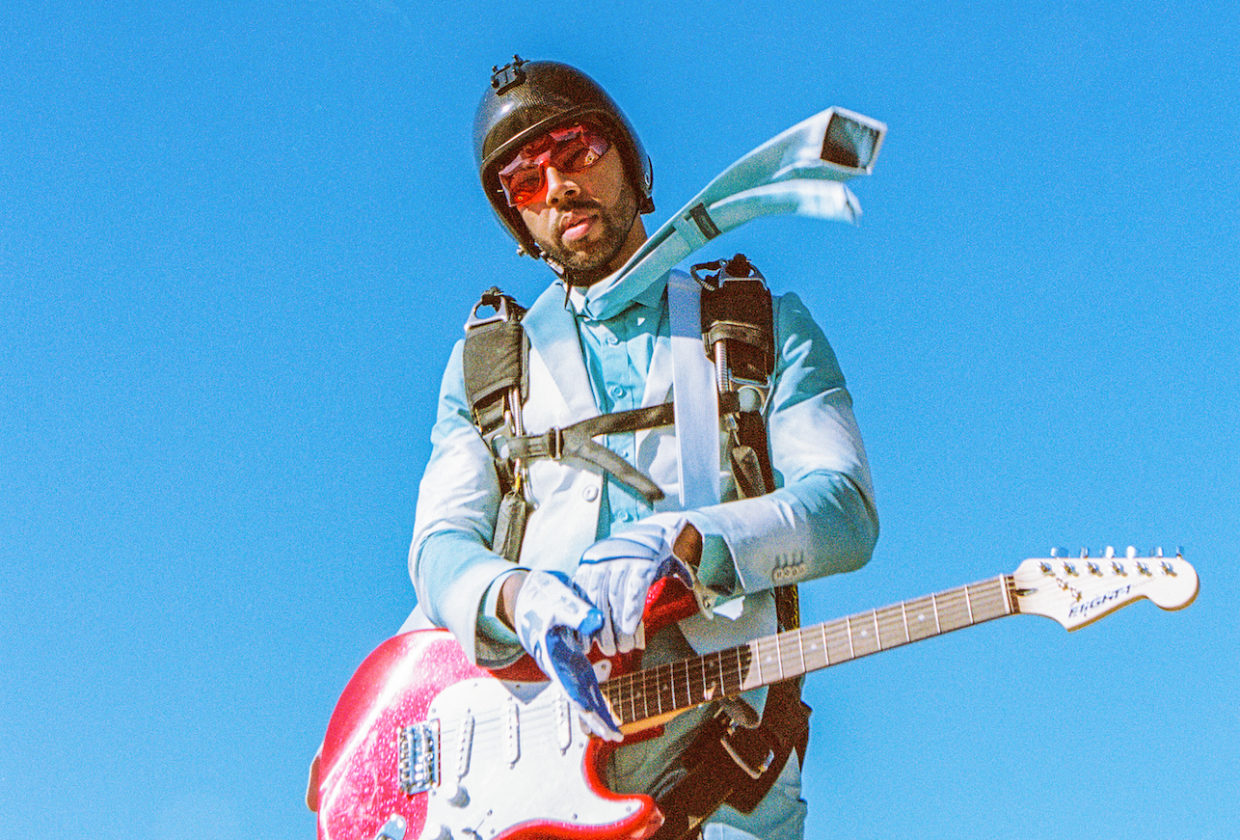

The story of Vic Mensa encompasses a discography that features socially conscious hip-hop songs like “Moosa,” cinematic rap dramas like “MACHIAVELLI,” and a musical detour by his punk rock band called 93Punx. The South Side Chicago native is a walking coming-of-age story whose life, thus far, has played out in subsequential chapters about growing up as the bi-racial child of a migrant father from Ghana and an American mother of Caucasian descent while battling severe depression, drug abuse and the social allure of gang culture.

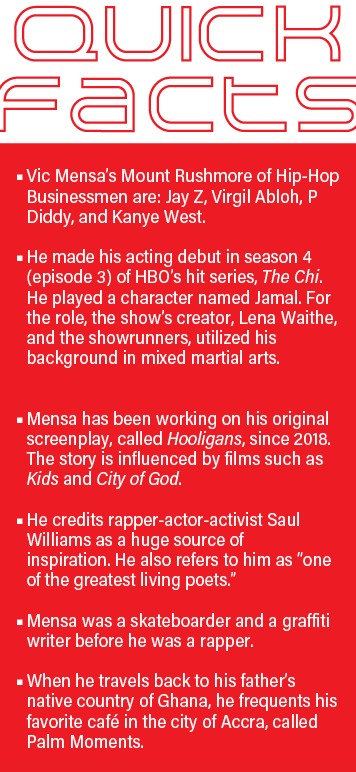

The chronological tale of Vic Mensa cannot be told without mentioning his best friend from childhood, Chance the Rapper. Before they were famous, the two like-minded emcees forged a bond with the formation of a hip-hop collective called SaveMoney. Mensa established the group in 2008, a time when he sincerely believed that he would either die before the age of 23 or join the “27 Club” shortly thereafter with the likes of other talented musicians who died at the age of 27, such as Robert Johnson, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Kurt Cobain, and Amy Winehouse. Today, Vic Mensa is a 29-year-old who’s a year and a half into sobriety. He’s also a revolutionary entrepreneur with foresight that extends far beyond his penchant for identifying his city’s brightest stars before anyone else. Although Chicago remains in his heart, Mensa’s ambition has steered his focus toward the native country of his father. He and Chance the Rapper recently co-founded a live music extravaganza in Accra, Ghana called the “Black Star Line Festival.” The inaugural event occurred on Jan. 6th and it garnered over 50,000 attendees.

Indeed, Vic Mensa has already lived a lifetime that very few real-life stories can parallel, and the best part is he’s writing it all down in what is shaping up to be a riveting screenplay based on his adolescence that he has tentatively titled “Hooligans.” Mensa is much more than a rapper. He’s also a rock musician, an activist, a philanthropist, a scriptwriter, and a businessman with a vision. We caught up with the Grammy-nominated artist to talk about what fans can expect from his highly anticipated sophomore album, the inspiration behind the Black Star Line Festival, his close friendship with one of the industry’s most iconic rock musicians, and more.

Music Connection: We understand that congratulations are in order! The Black Starline Festival that you co-produced with Chance the Rapper debuted in Accra, Ghana during the first week of January. When we think of some of the most polarizing Black music festivals of all time, the Harlem Cultural Festival (1969), the Afropunk Festival (founded in 2005), and the Roots Picnic (founded in 2008), immediately come to mind. What are some of the cultural music events that helped inspire the making of the Black Star Line Festival?

Vic Mensa: There was a festival that happened in the ‘70s at Independent Square (a famous venue in Ghana) called Soul II Soul with Tina Turner and some others. Honestly, I’ve never seen the documentary (a film based on the live event by Denis Sanders). My father was there, and he told me about it. At a later moment, they stated that it was kind of like an “African Woodstock.” “Festac,” which happened in Nigeria (during the year 1977), was like a diasporic and African meeting of the minds and was also an inspiration. But in truth, I never studied any of them. I know that they happened. I don’t think the primary inspiration for the “Black Star Line Festival” was other festivals; it was ideologies such as the Pan-Africanism of Kwame Nkrumah and the thoughtscape of Marcus Garvey, who was an inspiration to Chance and myself, as well. I do think that “Dave Chappelle’s Block Party” was very influential in this as well.

MC: One of the biggest differences between the Black Star Line Festival and the aforementioned concert events is that you seemed to be more focused on bridging the gap among Black musicians worldwide, whereas your predecessors based their events primarily on music curated by African Americans. Why was this a critical point of focus for you, as opposed to honing in on the Ghanaian artists in your father’s homeland?

Mensa: The entire idea of the festival was born of my inherited position as a bridge between Black American and Africa. When I began to consider the creation of a diasporic musical festival, it was for that purpose. The connection between us, the celebration of our similarities, our unique differences, and our shared and different histories. So, from the jump, when I started to dream of this, the unique selling point, in my mind, was that there’s this tremendous gap between Black musicians of the globe and their fans in Africa.

I just started to think about how unsustainable it is for us to continually pass over them because our booking agents don’t book us in [international locations such as] Lagos, Nigeria, or Ghana, and Senegal. They book us in London, Paris, and Berlin. So that’s where we go. That’s not because the people in Lagos, Ghana, and Accra don’t listen to and love our music; it’s because the opportunities haven’t existed.

MC: Your approach to executive producing this event sounds strikingly similar to Ryan Coogler’s vision for the first Black Panther film with Marvel, during the production phase as he was preparing to direct the movie. Are you familiar with this filmmaker at all?

Mensa: Hell yeah, I know Coogler. He brought me out to Flint, Michigan for the first time when the [contaminated] water situation there was receiving national attention. He organized this amazing event, and I came down there to perform, debuting a super-political song called “16 Shots.” It was an impactful, controversial, and substantial moment.

MC: You grew up in the city of Chicago, the son of a Ghanaian father and an American mother of Caucasian descent. How did your multicultural background and Chicago roots help you navigate through the developmental years of your artistry as Vic Mensa?

Mensa: I grew up listening to all styles of music. I grew up listening to African music in our home. My uncle, Kofi Sammy (from the Okukuseku International Band) is a pioneer of highlife music in Ghana. He was a contemporary and close friend of Fela Kuti (the legendary Nigerian musician who pioneered Afrobeat), who used to stay at my grandmother’s house. So, Afrobeat music, highlight music, Hugh Masekela’s music, and world music were all being played in our house.

My mom was a hippie in the ‘60s, and she attended Woodstock (1969). So, Jimi Hendrix, The Beatles, The Who, and other classic rock bands were being played. My parents were also huge fans of jazz music, so there was a lot of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Donald Byrd being played in my house. Really, there was no rap. But my Pops loved 2Pac. But not the music, he didn’t know nothing about his music; he just loved 2Pac’s revolutionary principles.

So, the music that was given to me by my family was eclectic and worldly. As I developed my own taste for music, I began with rock & roll. But as I became an adolescent, hip-hop became my language. I learned about a lot of different styles of music by exploring hip-hop samples. And then, I played in a band in high school with my brother, a world-class jazz musician named Niko Segal. So, at the same that I was starting to [rap] for real, I was finding the expression of my place in the world, which was giving me my identity in the context of America as a young Black boy.

I was also being introduced to more depth of the different styles of music that my parents were listening to. I was always a rock & roll kid, but the references were getting deeper as I was starting to hone my instrument. So, within that space, I was never a one-dimensional musical mind. Because I was just a fan, I still am. I’ve always been a fan of many different styles of music.

MC: That’s interesting. Who were some of your favorite rock bands when you were a kid?

Mensa: When I was a little kid, I was just into what my mom was into. So, Guns N’ Roses was my favorite band when I was a little kid playing “Sweet Child O’ Mine” on the guitar. But I think the first rock music that really spoke to me was Nirvana. By the time I was in high school, I got deep into Rage Against the Machine because it kind of just spoke to so many sides of what I loved, and later on, I think I became obsessed with The Clash.

MC: I used to love The Clash. They’re the best punk band ever!

Mensa: Yeah! The best band for sure! You know, later on, I got more into some hardcore punk shit like The Leftovers, The Crack, Fugazi, and shit like Joy Division...a lot of different shit. You know?

MC: Yeah. So, speaking of Rage Against the Machine, you and the lead guitarist have a lot in common. You’re both musicians from Illinois, you’re both bi-racial and his father is from Kenya. I’m curious, have you guys ever met?

Mensa: Are you talking about Tom Morello?

MC: Yeah, Tom Morello.

Mensa: That’s my brother!

MC: No way!

Mensa: That’s my boy! Me and Tom Morello do have a lot of similarities. We’re both super politically minded [and] of mixed race. Tom Morello’s my guy. He’s been solid with me for years. I think I first got in touch with Tom Morello when [Donald] Trump got elected. I’m just a huge fan of Rage Against the Machine. I’m sure he knew that before meeting me; I was also doing a lot of political music at the time, and he’s political. So, when Trump got elected, he did a concert in Los Angeles the same day of the [U.S. Presidential] Inauguration Ball. It was like the ‘Anti-Inauguration Ball’ and he had me come and play that show. It was me and Tom Morello playing with Public Enemy, also with Chris Cornell, and Audioslave. It was super dope! I’ve been rocking with Tom Morello ever since we did some music on one of his albums, and even when I was in a punk band, he brought us on tour with him.

MC: Whether it is music related, an anti-violent stance regarding Chicago’s youth, social or political, you’ve always been a visionary that takes the initiative. When you formed the rap group SaveMoney, what were some of the biggest dreams that you and Chance the Rapper shared with one another regarding your future? And how many of those goals have manifested now that you’re both in your late 20s?

Mensa: When I formed SaveMoney, I was focused on lyricism and stealing. I was on my hip-hop sh*t and I was just trying to get fly, I wasn’t trying to help the community [laughs]. We were problem children, thieves and brawlers. At the same time, I think SaveMoney always had this soul of being the antithesis of your average rap sh*t. Which I think developed in different ways through the years.

I met [Chance the Rapper] when we were both 14-year-olds, when we were both starting to rap and record. I think that the goal was always to be huge international artists and I don’t know how fully fledged that concept was in mind, in terms of specificity. I just knew I was good at this sh*t and that I had something to say and that I could make it. For all intents and purposes, I have to remind myself that I have done that. Although there are so many more things in my life that I intend to do. I thought that this rap sh*t would take me around the world. I thought that this rap sh*t would give me a platform where people like you want to speak to me and where kids listen to my lyrics and learn from sh*t I have to say in the way that I learned from Common, 2pac or Nas. All of that and more has taken place.

MC: Speaking of being an international artist, you blew up back in 2014 upon the release of “Down on My Luck.” The song dropped before the release of your debut album (The Autobiography) in 2017, and it was actually more popular internationally, in places such as Europe and Australia, than here in the U.S. How did touring in those continents spark your imagination as a creator and future entrepreneur?

Mensa: I think that I was just blessed to be able to have a global perspective at such a young age. I’m 29 now, I haven’t even hit 30, but I feel like I’ve lived a lot of lifetimes and I’ve been able to learn so much at a young age and experience so many different places. I’ve seen that humanity is much deeper than race, religion, creed, or culture. I feel blessed in that way. What it’s all taught me is that my true nature as this infinite being of consciousness is so deeply connected to every single thing, and I’ve seen so much of the planet.

There’s still a lot more to see, but I’ve seen a lot and I know that the things we don’t see are far more substantial than what can even be viewed by the naked eye.

MC: Earlier, I mentioned your debut LP, The Autobiography. What was it like working with the lead singer of Weezer (Rivers Cuomo) on one of the tracks from that album, called “Homewrecker?” He is an icon in alternative rock and a gifted songwriter.

Mensa: Weezer is one of my GOAT bands, I’ve always loved Weezer since I was a little kid. When I was in high school, I got into Pinkerton (Weezer’s 2nd studio album) and that’s the album where I found the sample for “Homewrecker.” That was one of the beats that I made on that album, in collaboration with No I.D. (a music producer from Chicago). I just looped the sample and rapped on it; No I.D. gave me drums. When I got Rivers into the [recording] studio, and he was in the booth singing, he sounded exactly like the Weezer of my childhood and it was so dope to me.

MC: Can you tell our readers about the making of your song “Kwaku?” I believe it depicts an origin story about you through the eyes of your father (Edward Mensa) shortly after he migrated to the city of Chicago from Ghana, right?

Mensa: It’s my Pop’s giving the background to me existing as I do. He’s close to the senior most-elder in his family lineage. My Pops is not a young man, he’s like 72 or 73. So, me recording my Pops in the basement of our house in my cellphone for that song was really just a small piece of the anthropological folkloric work that I need to do with my father while I have him, because we’re African people and a lot of our history is oral. That’s how we pass down tradition. Whereas my mother’s side of the family has a family tree.

MC: Much like “Kwaku,” another emotionally insightful track from your recent I TAPE EP is a song called “Moosa.” It details your effort to free your friend, Brian Harrington Jr. (aka King Moosa), from prison through the legal system. Can you give us the backstory regarding the song’s inception and your friend’s reaction to your work contributing to his early release?

Mensa: That’s probably the single most significant accomplishment in my life, thus far. Through a twist of fate, the intervention of God and by harvesting my own power [along with] coincidence and synchronicity, I was able to help this brilliant brother of mine named Moosa, who was sentenced to 25 years when he was 14, to get home 12 years early. I’m forever altered by that…I’m forever changed by that…Few things have affirmed my purpose in my core like seeing the fruit of my labor and my energy result in the freedom of my brother in that way.

MC: Your first studio album dropped nearly six years ago. Since then, you’ve released a number of EPs along with a side-project by your punk rock band, 93Punx. The time has finally come for Vic Mensa to release his second solo album. Can you tell our readers what to expect from your new LP, musically?

Mensa: My new album is coming out in the next couple of months. I’m excited for it, man. It’s definitely some of my strongest music in a long time and very representative of my truths, which is the most I can ask for from my music.

MC: You’ve evolved so much as a musician and a person since fans were first introduced to you as a teen. What are some of the music genres that you’re going to incorporate into your second studio album?

Mensa: It has African influences, rock inspiration, jazz inspiration and soul samples. I’m doing quite a bit of the [music] production for the album. Lyrically, it’s the story of redemption and I do believe that it’s going to be instrumental in directing my momentum into a new chapter of my life and my time as a performing musician.

MC: Can you tell our readers about one of your favorite collaborations from the album?

Mensa: There’s a joint on there with Common that’s on my mind right now, because I’m [currently] on the South Side [of Chicago], and the song is just a play-by-play description of my environment on the South Side of Chicago. That’s a song that I really love.

Contact sashabrookner@gmail.com