He is at top of the pop game this season. Jack Antonoff has multiple co-writes and production credits on two hugely anticipated projects—Taylor Swift’s #1 release Lover and Lana Del Rey’s Norman Fucking Rockwell. Other recent contributions include St. Vincent’s Masseduction and Lorde’s Melodrama plus tracks with Carly Rae Jepsen, Pink, Sara Bareilles, Troye Sivan, Christina Perri, Rachel Platten, Kevin Abstract and Zayn.

He was a kid growing up in New Jersey, and once Jack Antonoff began making music, he never stopped. But despite signing his first record deal at age 18, he spent a decade toiling away in virtual obscurity.

Antonoff first came on the radar with his hard-touring band Steel Train. Joining with Nate Ruess and Andrew Dost he hit the mainstream in the band fun., powered by his co-written anthem “We Are Young” and “Some Nights.” He got personal with Bleachers, the project he instigated while still working with fun., tracking two full-lengths and contributing music to the film Love, Simon.

Most recently, Antonoff has teamed up with singer-songwriter Sam Dew and Kendrick Lamar collaborator Sounwave as Red Hearse. Their self-titled full-length debut was released on Aug. 16.

MC caught up with Jack Antonoff on a recent Los Angeles visit when Red Hearse was in town to record an appearance on The Late Late Show with James Corden. Antonoff’s East Coast origins became immediately evident with the intensity of his rapid-fire conversational velocity.

Music Connection: The Taylor Swift album, Lover, comes in with such a sense of expectation. Having co-written six songs on her previous release, Reputation, and contributing to her album 1989 what was the thought on the new project, specifically the arc of sustaining a storyline across the span of tracks?

Jack Antonoff: It’s always albums with her—documentaries about a period of time; statements that are sewn together into specific stories that are sonic. That’s the only stuff that I can even make sense of. That’s the thread in the albums I make. We’re always talking about that thread, about that North Star. That’s what a great album is, whether it’s one person in the room, two people in the room or 10 people in the room.

There’s this North Star that’s imaginary, and we’re all looking at it and trying to get there. There would be no reason to be in the studio if it wasn’t a group of people trying to reach this place. That’s the glory of it, to have this crazy idea and chase it.

MC: Even as we continue in a singles world, why do you believe that albums are essential?

MC: Even as we continue in a singles world, why do you believe that albums are essential?

Antonoff: I love songs to death—a song can change the world. But a song in context…a great album is a journey to take you out of yourself for an extended period of time. Not to capture one feeling or moment, but to capture an entire period of your life. I think about Magical Mystery Tour by the Beatles, Heart of Saturday Night by Tom Waits, or Blue by Joni Mitchell—it wasn’t just a song I listened to and played in a certain mood. These albums lifted me for years. They carried me throughout an entire period of my life.

MC: So why the current focus on singles? Is this industry-driven?

Antonoff: I think the conversation that the album culture is on the decline is a complete lie. The best and most important artists happening currently and historically have always been album artists. The industry tends to preach a different gospel because I think they can control a singles artist more than they can control an album artist.

When someone says to me “albums are dead” I say to them, “It’s because you don’t listen to albums.” But all of the people that I work with do. When I play shows it’s audiences of album people who know every song. That’s who I want to speak to.

MC: “Archer,” the lead single on Taylor Swift’s Lover, was supposedly written and tracked by the two of you in a few hours. You are well known for not laboring over tracks for an extended period of time. How does your deployment of analog synths work for this immediacy?

Antonoff: I don’t use any software—I record in ProTools and I move sounds around a lot, but I won’t record anything soft. Say you’re working on the Prophet 5 or a Juno 6 and you find a sound and you like it. If you walk away and come back, it’s not going to sound the same. Every time you play something on an analog synthesizer, it’s the only time it’s going to sound like that. You can never recall sounds—it’s impossible. It’s the way the thing is feeling or moving or coming through the console. I like knowing that if something happens and you’re playing a Moog Model D and it feels incredibly cool, there’s no getting it later.

That’s my ultimate outlook on recording and production and writing. You are endlessly messing around until you find those moments. And if you are in contact with something that can be easily duplicated, you’re hurting yourself from finding that moment. You want to walk on the tightrope. You want to be right on the edge. You want to be playing an instrument that you can never play the same way again.

MC: Are these decisions made instinctively? And what do you think listeners will vibe from this immediacy?

Antonoff: If you surround yourself with those kinds of things I think you make quicker decisions and you make better decisions as to what is good and what cuts to the bone. Whereas if you have some soft synths and you can pull up the same sounds over and over again the risk is so much lower. I’m at a point in my career where I can buy some of those synths, obviously. I don’t care if I’m making a pop record or a country record; I believe that even a totally untrained ear can feel on a gut level the difference between something in a computer versus the low end on a Moog Model D or when you hit the chorus button on a Juno 6.

MC: Speaking of immediacy: you just recorded “Looking for America” with Lana Del Rey, a message song recorded with just guitar and voice.

MC: Speaking of immediacy: you just recorded “Looking for America” with Lana Del Rey, a message song recorded with just guitar and voice.

Antonoff: It’s all happening right now. Lana and I have been working together for a long time now, we made an album, Norman Fucking Rockwell, and we made a lot of other things. And after the shootings in El Paso and Dayton, she called me and said, “I want to write something.” It’s amazing. We got together in Los Angeles and went to Conway Recording. I took out a guitar and we came up with “Looking for America.” We produced it quickly because we wanted to put it out in this moment.

Nowadays, it’s so easy to share your opinion and put it out online if you are an artist or a musician or a poet. Maybe back in the day something would happen in the culture and Joan Baez or someone would record a song and then play it that night and that’s how people would react to it.

MC: The tracks from the new Lana Del Rey project focus on her as a storyteller, with an almost folk narrative approach.

Antonoff: I think there’s a time for that—things going on that are well addressed by folkie storytelling. But how do we bring pieces of that and bring it into the future?

With certain kinds of storytelling the way you record it is interesting. What is the perspective of this story? Is it the voice of God with reverb? With a lot of the records I’ve been making lately, when the lyric is personal, I want to hear it super dry and super upfront, like someone is saying it to me. If it sounds like a huge important idea, then stack it, drench it in reverb and let it sound like the voice of God.

MC: “Greenlight,” which you co-wrote and produced with Lorde, has that upfront effect.

Antonoff: With the lyrics Lorde is writing and what she’s singing, it would be unfair to mask the vocal. Then it gets fun with panning and movement. But when a story is that specific, we welcome that challenge of having a very dry vocal coming at you. It’s so much harder to do; to get that one vocal—you’re hearing every inflection, whether it's compressed or not compressed, it’s right there.

MC: You have a studio in Brooklyn that you’ve characterized as a safe space for artists. Is this a physical or a psychological dynamic?

Antonoff: Once you step into a big studio you can get a little tight. You know how much money you’re spending, what is at stake, and there is a staff of people. My whole experience in making records is the same, whether I was messing around as a teenager, messing around as an adult, or working with a friend or a big artist: Whatever it is, everyone is just trying to access that feeling of when they wrote the song and when they are in it. The ultimate expression of recording as an art form is to capture and document that perfectly. To get as close to the bone as possible.

MC: How do you define the space physically?

Antonoff: With my place in Brooklyn I tried to create a place where everything is up all of the time. All of the chains are as great as if I was working on a record in a big studio, but it’s in a really small room and there’s crap everywhere and it feels easy and loose. What happens in that room is I’m able to get those feelings that you’re in the bedroom demoing something but I’m recording it on all of that gear I need to be recording it on so that it’s final.

MC: We understand you prefer a very small core of creators, maybe just you and the artist?

Antonoff: I love collaborating. In my experience, less is usually more, especially if you have a crazy big idea of what you want to do and you can find a partner. With a small group, you’re speaking in a language that nobody else knows. In my experience, that idea can actually be realized if you conceive of it in a small group. When you open it up and other people begin bringing their ideas to that concept there’s different emotions and feelings and it can sometimes fall apart.

Nine times out of 10 that first crazy idea you have is the thing. And then the hardest job of being an artist or a producer or a songwriter is actually staying on that road and not letting anyone else push you the wrong way, put the wrong beat on it, take the feeling out or change the one lyric that means the most to you.

MC: In creating songs, do you think it’s important that they can work completely stripped down, independent of arrangement or production?

Antonoff: You want a certain number of songs on an album that can just work as songs or pieces of poetry if you read them. Then you have these other things that are these weird architectural concepts that only work as a part of a whole, and if you removed them it would all dissolve. It’s like a Beatles theory. On any Beatles record––especially the later ones–there are a handful of songs that are unimpeachably perfect songs that you could just sit at your piano and play. And then there are others that make sense with the labyrinth of ideas and productions that are happening.

That’s what makes it so glorious. St. Vincent reminds me of that. You get the things that are incredibly perfect and classic and things that are bananas that shouldn’t work but do.

MC: The Kevin Abstract full-length, Arizona Baby, has a very hermetic and consistent sound.

Antonoff: He’s one of my favorite living artists at the moment. We got in the room and that was it: the sound was very specific, a Moog Model D pitched super high, so it was very West Coast sounding, a specific Hofner bass, a specific Telecaster, a specific drum set at Electric Lady Studios recorded in a very specific way—a little sandbox. It’s all played live in the room and organic, with sounds no one has heard before. With that album, we knew it was happening right now. We had to get it down and recorded because the moment was upon us.

MC: You have a new project called Red Hearse. How did this trio come together?

Antonoff: It was birthed out of three guys, we’re all friends and we all were equally not into the way a lot of records get made with all these tons of different people flying all over the place. So what if the three of us got in the room and recorded music and that was it? And there’s not a single other writer, producer or player—just three people making a record. Sounwave from LA, Sam Dew from Chicago and I’m from New Jersey. We have a large footprint of America mapped out with this project.

MC: The backing vocals on the Red Hearse song “Half Life” are reminiscent of Electric Light Orchestra (ELO).

Antonoff: My number one inspiration is Jeff Lynne for a number of reasons. Specifically because he’s the one person out there, to my estimation, who really balances production, engineering writing and artistry all together. I fit in all of those spaces and they’re all different. Jeff Lynne nails it on all angles.

MC: For the past couple of years you have been producing The Ally Coalition Talent Show in New York with artists including Lana Del Rey, Lorde, Regina Spektor and Hayley Kiyoko. It has raised funds for organizations for LGBTQ youth centers. We love that you call it a “talent show.”

Antonoff: When we have an audience, it’s really easy to raise money. And we make that event something fun and exciting and inspiring that people look forward to, and not some stuffy thing that they hate going to. It’s for a good cause.

Once a year, if we can raise a lot of money that goes to local LGBTQ shelters––with nothing in the middle. I get my friends together that I’ve made records with that year and have a bunch or surprises. It’s just get on stage, be totally loose, play songs acoustic, have a great time and raise a ton of money. That’s the least you can do if you have an audience.

If it’s something as vital as kids on the street, everyone is looking at a much bigger thing than themselves.

MC: You spent almost 10 years in virtual obscurity before your breakthrough into the mainstream. What was happening during that period? Did the world catch up with you?

MC: You spent almost 10 years in virtual obscurity before your breakthrough into the mainstream. What was happening during that period? Did the world catch up with you?

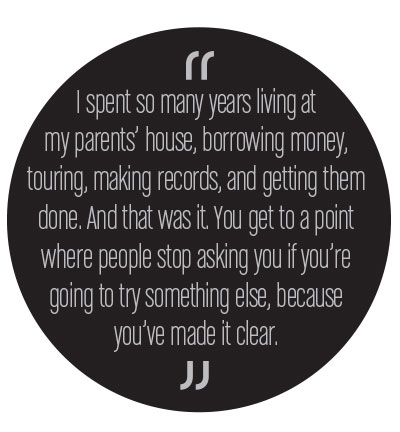

Antonoff: I had no commercial success in any sense, for my first 10 years, which I love. I think part of making records and touring is about this illusion, about the conversation in your head that you can’t let go of, these lyrics you have to say. If motivation of the world responding to your art inspires your art, then you really should not be making art. It’s not something you do because you enjoy the reaction; it’s something you do because you have to.

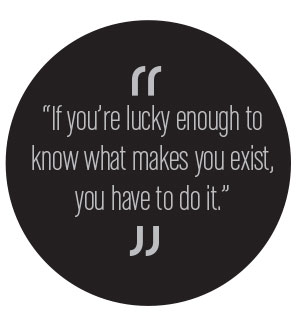

That’s not to say it’s not the great joy of my life to be heard and have the ability to go buy some of these synthesizers, and work with the people I do, and be in these nice studios and hear my music through a giant Neve. But all of that aside, it doesn’t really matter. All that matters is that I have to do it or I wouldn’t have an existence. If you’re lucky enough to know what makes you exist, you have to do it.

MC: Was this a frustrating period for you, prior to your breakthrough?

Antonoff: I spent so many years living at my parents’ house, borrowing money, touring, making records, and getting them done. And that was it. You get to a point where people stop asking you if you’re going to try something else because you’ve made it clear. And I chose being the ultimate definition of a loser because that’s a pretty small price to pay to have the glory of feeling yourself with music, or poetry and recording. It was a long time before anyone cared.

MC: How did the success of the band fun. illuminate that future path?

Antonoff: It was the beginning of people letting me in the room. Writers and producers who are reading this know: Sometimes you’re in that studio alone and you think this is so happening, and no one wants to hear it from you, because you have no way in the door. No one is vouching for you because you have no hits or stats. With fun. I knew I had a shot. I was so proud that I was having success and the door was open, but it wasn’t going to stay open forever. And I had to work my ass off. I still feel like that every day. None of this is permanent.

Contact Jamie.Abzug@rcarecords.com