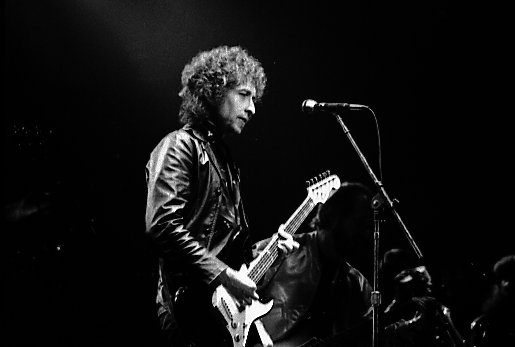

Bob Dylan’s 2025 tour continues on May 16th at The Hollywood Bowl, followed by dates on May 20th Nampa, Idaho Ford Idaho Center Amphitheater, May 22nd Spokane, Washington ONE Spokane Stadium, May 24th Ridgefield, Washington Cascades Amphitheatre, and May 25th Quincy, Washington The Gorge.

On June 27th, Columbia Records will release Barbra Streisand’s album of duets, The Secret Of Life: Partners, Volume Two. Barbra and Bob team on “The Very Thought of You.”

In her 2023 autobiography, Bottom of Form

My Name is Barbra, Streisand mentioned she’d read an article about Dylan’s archive housing a letter from her.

“Back in the 1970s he sent me flowers and a charming note, written in colored pencil with childlike letters, asking me if I would like to sing with him,” Streisand wrote.

When Yentl was due in 1983, directed by Streisand, Dylan sent a copy of his album Infidels, indicating he was looking forward to watching the film, and wanted to work with her.

“You are my favorite movie star,” Dylan wrote. “Your self-determination, wit and temperament and sense of justice have always appealed to me.”

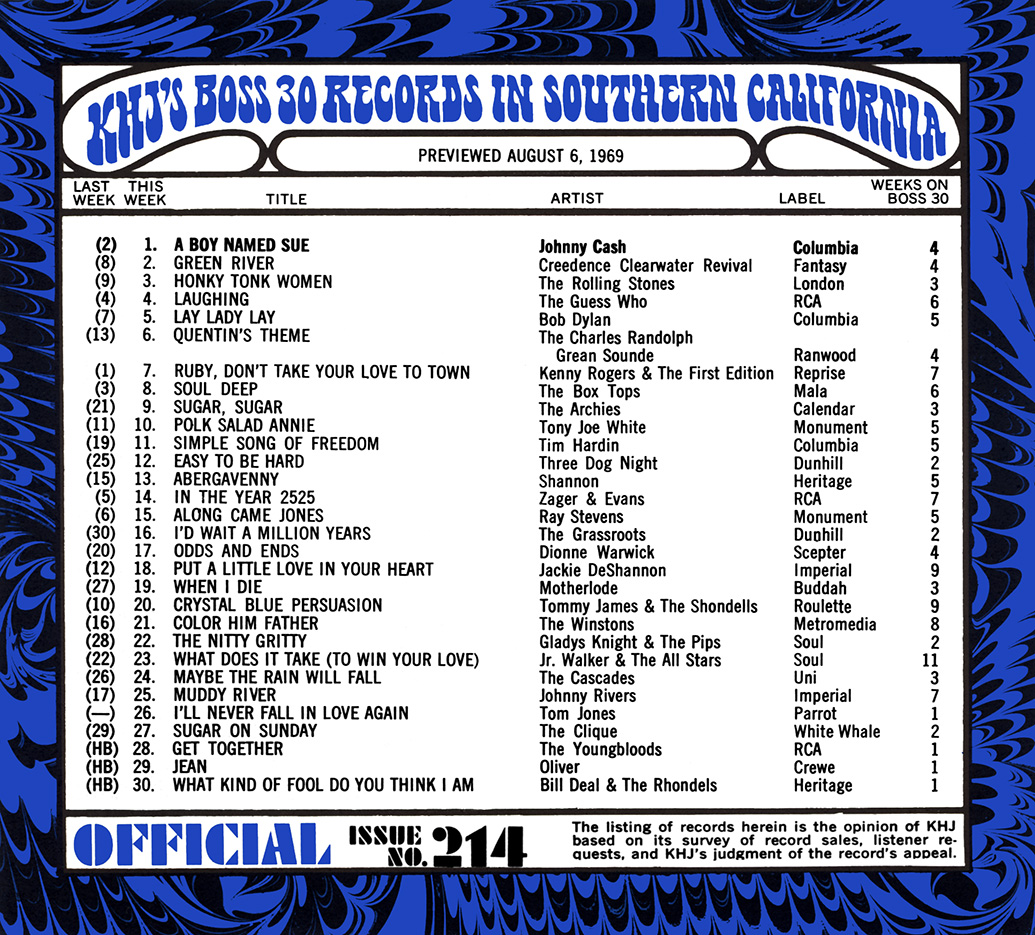

I conducted an interview with Johnny Cash in Anaheim CA. at the Royal Inn that was first published in the August 16, 1975 issue of the now defunct UK music weekly Melody Maker. Johnnywas appearing at a Christian Booksellers Convention promoting his autobiography, Man In Black.

I told Cash we shared the same February 26th birthdate, and asked him to talk about Bob Dylan.

"I became aware of Bob Dylan when the Freewheelin’ album came out in 1963,” recalled Johnny. “I thought he was one of the best country singers I had ever heard. I always felt a lot in common with him. I knew a lot about him before we had ever met. I knew he had heard and listened to country music. I heard a lot of inflections from country artists I was familiar with.

“I was in Las Vegas in '63 and '64 and wrote him a letter telling him how much I liked his work. I got a letter back and we developed a correspondence. We finally met at Newport in 1965. It was like we were two old friends. There was none of this standing back, trying to figure each other out. He's unique and original. I keep lookin' around as we pass the middle of the 70s and I don't see anybody come close to Bob Dylan. I respect him. Dylan is a few years younger than I am but we share a bond that hasn't diminished. I get inspiration from him.

“We’ve gone fishin’ on my boat dock for hours and haven’t said a word.”

Every year since 1975 I’ve conducted an interview or had email exchanges with musicians and writers about Bob Dylan.

As Dylan’s 84th birthday arrives on May 24th, it’s appropriate to display some responses from my encounters with them.

On November 19, 1979, drummer and friend Jim Keltner, invited Knack drummer Bruce Gary and I to the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium to see Dylan’s Slow Train Coming concert.

I had a very brief chat with Dylan backstage. I mentioned interviewing Johnny Cash and Phil Spector for Melody Maker. He inquired about Spector. During 1977, Dylan, Allen Ginsberg and I attended Spector-produced Leonard Cohen recording sessions at Gold Star studios for Death of a Ladies’ Man.

I told Bob that Phil talked about R&B vocalists, also citing “Dion, John, Paul, Elvis, Bobby Darin, and Johnny Cash as great singers.”

Bob then removed his tinted sunglasses and smiled. He has blue eyes like Eva Marie Saint, Charles Bukowski, and Kris Kristofferson. He offered a firm handshake, and replied, “Johnny Cash is a friend of mine…”

Johnny Cash: I became aware of Bob Dylan when the Freewheelin’ album came out in 1963. I thought he was one of the best country singers I had ever heard. I always felt a lot in common with him. I knew a lot about him before we had ever met. I knew he had heard and listened to country music. I heard a lot of inflections from country artists I was familiar with.

I was in Las Vegas in '63 and '64 and wrote him a letter telling him how much I liked his work. I got a letter back and we developed a correspondence. We finally met at Newport in 1965. It was like we were two old friends. There was none of this standing back, trying to figure each other out. He's unique and original. I keep lookin' around as we pass the middle of the 70s and I don't see anybody come close to Bob Dylan. I respect him. Dylan is a few years younger than I am but we share a bond that hasn't diminished. I get inspiration from him.

Dr. James Cushing: When we think of Bob Dylan geographically, our first associations are with Hibbing, in the Mesabi Iron range of northern Minnesota, then Greenwich Village around 4th Street, then upstate New York. But the truth is, Los Angeles has been Dylan’s primary residence since 1973, and the city has played a substantial role in Dylan’s life and career. How appropriate that the man who wrote “he not busy been born is busy dying,” having made enough money to live anywhere he wants, has made his home in the city of radical self-invention.

Robby Krieger: (The Doors): I saw Dylan perform in 1963. I was in high school in Menlo Park, near San Francisco. There were some guys there from Boston and New York in the dormitory with me and they were into Bob Dylan. I had never heard him before. They had his debut LP. So, they played the first album and I got totally into him.

On Dylan’s first album I really liked his guitar playing. I thought he was a great fuckin’ acoustic player. He did some stuff that was pretty damn good. And his harmonica work. I had never heard anyone play harmonica like that. Not a blues harmonica player sucking in the notes. I was amazed he could do all that stuff and sing at the same time.

He came to Berkeley for the first time and we saw him at the Community Theater. We just got tickets. I wasn’t hooked up then. (laughs). It was a good experience. He had the buckskin jacket. I bought into the whole thing, basically. I later bought a harmonica rack holder. When I saw him live, I sort of realized at the time there were some interesting and unique tunings on stage. I thought he was pretty cool at that first concert, and then the week after that we saw Joan Baez play at Stanford University.

I loved his Bringing It All Back Home LP. That was my favorite. It all made sense. The lyrics fit exactly what I was thinking when I was acid. It registered, you know. ‘Wow. I’m listening to this guy.’

My favorite song was “Mr. Tambourine Man.” I might have been in my band then called the Psychedelic Rangers. I had been playing guitar for a couple of years and started at age 15. At the Long Beach concert at first, I didn’t know what to think. Because I was expecting it to be how it was before. But then I realized this. I didn’t really get into Dylan until I saw him the next time in Long Beach in ’65. An auditorium. That’s when he first came out with the electric set. Not only that, but I was on my first acid trip. It actually was not even acid but Morning Glory seeds. I think I schlepped down from Menlo Park.

I went by myself. I had two tickets, and I had taken these seeds with my girlfriend and she didn’t want to go. So, I went by myself and my mind was blown. I expected him to be the same as he was earlier in Berkeley, and here he comes out with an electric band and wearing a Hollywood Zoot suit. I didn’t know what to think. In Long Beach he was totally different. That was one thing about Dylan that was always great. He always changed. I loved Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited album. I loved Michael Bloomfield’s guitar playing on that album and loved Bloomfield on the first Paul Butterfield Blues Band album.

I never saw Bob Dylan again except when the Doors were being inducted into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame when the ceremony was held locally in Los Angeles at the Century Plaza Hotel.

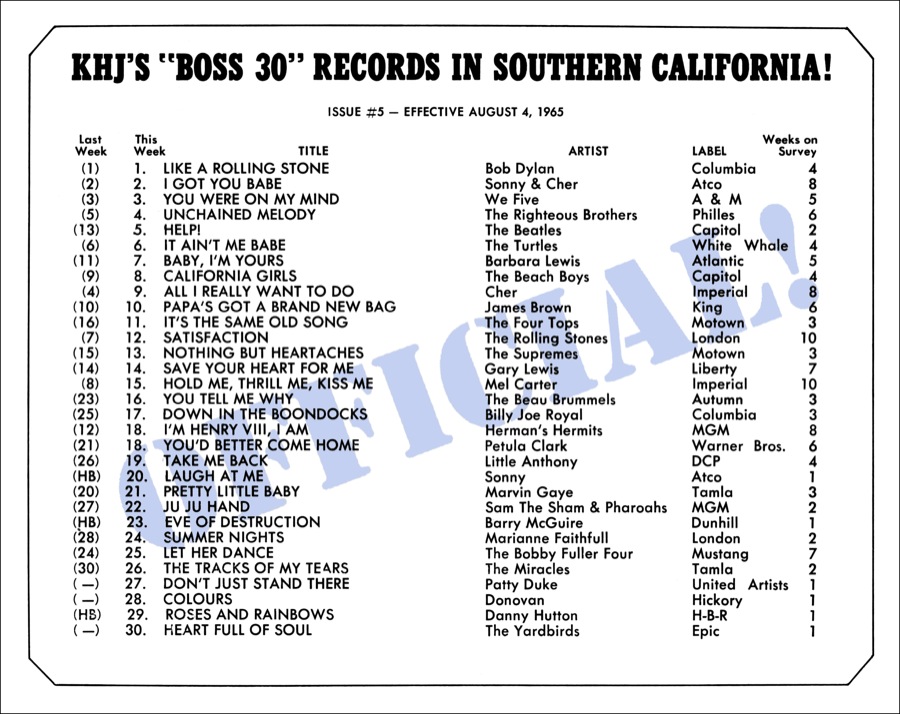

Al Kooper (Multi-Instrumentalist): On “Like A Rolling Stone,” I was waiting to see what chord they were going to do. There was no music or lead sheet, or anything. I was just playing organ by ear and I didn’t want to be the one making a mistake because I was doin’ like a rebel run there.

I was supposed to play guitar on that record. I packed up my guitar when I heard Michael Bloomfield warming up. It never occurred to me that somebody my age, and my religion could play the guitar like that. That was only reserved for other people. It never even occurred to me that that was an option for someone my age and my color. I had never seen that, or heard that up to that day. So, that pretty much ended my guitar playing by and large.

Robbie Robertson (The Band): There was a thing that happened between Bob and The Band on stage that when we played together that we would just go into a certain gear automatically. It was like instinctual, like you smelled something in the air, you know, and it made you hungry. (laughs). It was that instinctual. And the way we played music together was very much that way. And whether, we were playing in 1966, or 1976, or when we did the tour together in 1974, we would go to a certain place where we just pulled the trigger.

It was like ‘just burn down the doors ‘cause we’re coming through.’ And it was a whole other place that we played when we weren’t playing with him. So, it was like putting a flame and oil together, or something.

Well, we didn’t change. I don’t know that this has ever happened to anybody else. And it is a phenomenon. And that’s why I feel bold enough to refer to it as a musical revolution. Because the world came around. We didn’t. We didn’t do anything that much different. [laughs]. We just went out there and hit it between the eyes. And now people have a completely different reaction to it. And I thought ‘that’s kind of incredible that the world actually came to this place. And I don’t know who else has been through that.

Chrissie Hynde (The Pretenders): Bob Dylan's "Forever Young” has got such a beautiful lyric. I just love it. He's the pride of our generation. The song is genius. I'll tell you another great Dylan album, that was not one of his most popular ones, Shot Of Love. The song, "Lenny Bruce.”

Time Out Of Mind. It’s one of his best albums. He just sings magnificently, for a start. They're just great songs. Bob always writes impeccable songs, but my suspicion is that he's a little impatient in the studio. On this one, he really stuck it out and got gorgeous vocals. The singing is fantastic. The songs are so well crafted and they just got the great sound for each song. You don't feel like he just got a band in, wheeled them in and played all the songs and left. Each song is very carefully thought out. Obviously, that's a lot in the production and I'm sure that's Danny Lanois who masterminded that. Jim Keltner is the perfect drummer for any band if you ask me. He's great with Bob Dylan. Keltner is a genius drummer. I love that guy.

Kenneth Kubernik (Author): There is another American original, a musician whose body of work, scope of influence, and inscrutable personality mirrors so many of Bob Dylan's most singular attributes. Pianist Keith Jarrett is not a name that leaps to mind when talkin' 'bout Bob's imperishable impact, that litany of artists long identified with his idiosyncratic approach to song craft, interpretive wanderlust, and rousing conviction.

There is nary a one that reeks of jazz. But Jarrett - revered by players and serious students of improvisation, reviled by the jazz constabulary for his irascible nature - has, since the '60s, spun closely within Dylan's musical orbit. When jazz was moving uncomfortably towards rock and funk, Jarrett had his trio perform "My Back "Pages," and "Lay Lady Lay," coping a Floyd Cramer groove more redolent of Nashville's skyline than Manhattan's hot house revelries.

In an interview with England's Melody Maker, Jarrett cited Dylan's insight that artists "walk a razor's edge," when asked to describe the opaque process behind his mesmeric solo piano recitals. More than Monk and Miles, Trane and Bird, Jarrett found common cause with Dylan's redoubtable independence of thought and action. It is amusingly apt that Dylan, in recent years, has turned to performing the American songbook - "standards" - that provide the beating heart of every educated jazz musician. He's on Jarrett's turf here and one can only imagine that aching croak nestled inside the pianist's ineffable accompaniment. Wonder boys...”

Outside of maybe Bob Marley and Jimi Hendrix, no popular musician commands a more robust, enthusiastic international following than Dylan. His “voice” is heard in every language that speaks through music to celebrate the resiliency of the soul against the tides of a world gone wrong.

Jackson Browne (Singer/Songwriter): What Bob Dylan did for me, everybody and our generation it will never have to be done again. The way he opened up our thinking and our feeling and our view of the world only has to be done once. Maybe it’s done in other fields like film and painting and other art. As a people we’re constantly growing, expanding but the changes that Bob Dylan brought to rock and roll and songwriting are permanent. They’re part of us. People who are just being born into it now are being born into a world that wasn’t that way until Bob Dylan made it that way. It’s a particular skill to write something in a few words that speaks volumes. It is very difficult to say how I feel and how I think about Bob Dylan in a few words.

Howard Kaylan (The Turtles): We recorded cut “It Ain’t Me Babe” and met Bob one night. All of us, as singers and performers keep those great songs in the pipeline so they are not forgotten. It doesn’t have to be a great Bob Dylan song or a Tim Hardin song or even a great Leiber and Stoller song. If it’s great and forgotten you kind of feel like you are a missionary as far as getting those things to the public.

Al Stewart (Singer/Songwriter): When the Byrds’ released “Mr. Tambourine Man,” [June of 1965] and Dylan did “Like A Rolling Stone,” I thought, “My God!” This folk-rock thing was in the back of my mind as being interesting, but I thought it had no commercial applications whatsoever, and all of a sudden, it’s the biggest thing in the world. And I thought, “That’s it. I’m going to be a folk rocker because that’s the future.”

Roger McGuinn (The Byrds): Our producer Jim Dickson was definitely a large part of the formation of the group and the attitude. It was his pick to do ‘Mr. Tambourine Man.’ He got a demo of it before (Bob) Dylan released it. Jim loved the song. We didn’t get it. He had to bring Bob Dylan around to the World Pacific Studio for us to do the song at all. Dylan came over with Bobby Neuwirth and we played ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ and “All I Really Want To Do’ for Dylan and Bobby, and Neuwirth said, “wow. You can dance to it.’ After ‘All I Really Want To Do,’ Dylan responded, ‘what was that?” And we responded, ‘That was one of your songs, man.’ ‘I didn’t recognize it,’ he said. (laughs).

When I recorded the vocal on the Byrds’ ‘Mr. Tambourine Man” I was trying to place it between Dylan and John Lennon. Dylan’s stuff is brilliant. I coined the term that he was the ‘Shakespeare of Our Time.’ It was like knowing Shakespeare here. Dylan was carrying on Kerouac and Ginsberg.

Chris Hillman (The Byrds):One thing I’ve said before, and what our manager Jim Dickson drilled into our heads, the greatest advice we ever got, and he said, ‘Go for substance in the songs and go for depth. You want to make records you can listen to in forty years that you will be proud to listen to.’ He was right.

Bob had written it like a country song. Dickson said, ‘Listen to the lyrics.’ And then it finally got through to us and credit to McGuinn, mainly Jim arranged into a danceable beat. The Byrds do Dylan. It was a natural fit after ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ was successful. Roger (then Jim) almost found his voice through Bob Dylan, in a way, literally voice through Bob Dylan in a sense.

And then we start doing some Dylan stuff. ‘Chimes of Freedom.’ Great song. ‘All I Really Want to Do.’ At Monterey we included Dylan’s ‘Chimes of Freedom.’ I didn’t realize how beautiful that lyric was until years later. ‘Chimes of Freedom’ is a killer. It’s just one of Dylan’s beautiful songs, and he was just peaking then.

Steven Van Zandt (Actor/Guitarist/Record Producer): As a guitar player, I've played Dylan’s songs with Bruce [Springsteen] and in top 40 bands earlier. The Byrds introducing him to the world, really, with “Mr. Tambourine Man” was a major factor. I can't give them enough credit for that. I don't know if Bob Dylan would have been accepted at Top 40 radio if it hadn't been for “Mr. Tambourine Man.” That gang has been a great service to the world. I was a huge Byrds' freak. Still am. They lead you to Bob.

I play a lot of Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde. We usually don’t play a lot of Bob’s things that classic rock stations are playing, like “Tangled Up in Blue.” I’ve programmed Rod Stewart and the Faces covering ‘The Wicked Messenger’ from John Wesley Harding and Jimi Hendrix doing “All Along the Watchtower” from the same album.”

Daniel Weizmann: It's no accident that Dylan ultimately settled in Los Angeles to the degree that he ever settled anywhere. As a cowboy-pioneer of language crossing the American landscape, he knew that the Pacific is the end of the line. You haven't completed the journey until you've arrived. Also, Dylan has always had showbiz in the blood--he's a cinematic song and dance man and classic Hollywood iconography is always showing up in his work. For our greatest songwriter, L.A. is adversary, inspiration, hideaway, and shoreline.

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015's Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016's Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017's 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll TV Scenes) is scheduled for a 2025 publication date.

Kubernik’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown is in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett was published in 2019 by Oxford University Press. Brackett is a Professor of Musicology in the Schulich School of Music at McGill University in Canada. Harvey joined a lineup which includes LeRoi Jones, Johnny Otis, Ellen Willis, Nelson George, Nat Hentoff, Jim Delehant, David Ritz, Nelson George, Camille Paglia, Ben Fong-Torres, Jerry Wexler, Jim Delehant, Ralph J. Gleason, Greil Marcus, Cameron Crowe, Richard Cromelin, and Paul Nelson.

The New York City Department of Education will be publishing for fall 2025 the social studies textbook Hidden Voices: Jewish Americans in United States History. Kubernik’s1976 profile/interview with concert promoter Bill Graham on the Best Classic Bands website Bill Graham Interview on the Rock ’n’ Roll Revolution, 1976, Best Classic Bands, is included.

Harvey wrote the liner notes to CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

During 2006 Kubernik spoke at the special hearings by The Library of Congress in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 he appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in their Distinguished Speakers Series. Harvey spoke at The Grammy Museum in Los Angeles in 2023 discussing The Last Waltz music documentary.

Photo by Jean-Luc is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.