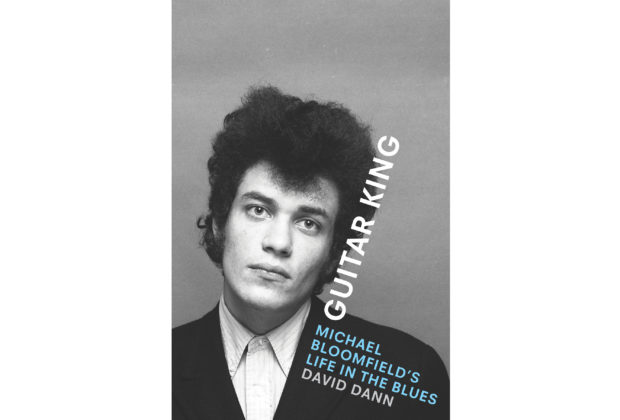

Guitar King: Michael Bloomfield’s Life in the Blues from author David Dann will be published mid-October by the University of Texas Press. This first comprehensive biography on the late and influential Michael Bloomfield brings to life the electric-guitar virtuoso who helped transform rock & roll in the 1960s and made a lasting impact on the blues genre.

Bloomfield (1943–1981) remains beloved by record collectors and fans nearly 40 years after his untimely death.

The 700 page monumental examination takes readers backstage, onstage, and into the recording studio with this virtuoso. Music historian and writer Dann tells the stories behind Bloomfield’s work in the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and the Electric Flag, as well as on the Super Session album with Al Kooper and Stephen Stills, Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, and soundtrack work with Peter Fonda and Jack Nicholson.

Dann’s chapters are vivid and drawn from meticulous research, including more than 70 interviews with the musician’s friends, relatives, and band members.

Dann brings to life Bloomfield’s worlds, from his comfortable upbringing in a Jewish family on Chicago’s North Shore—father Harold Bloomfield made a lucrative living making kitchen utensils as well as salt and pepper shakers—to the gritty taverns and raucous nightclubs where this self-taught guitarist helped transform the sound of contemporary blues and rock music.

David Dann is a commercial artist, music historian, writer, and amateur musician who worked for many years in the news industry, including serving as co-publisher of an award-winning Catskills weekly. Most recently, he was the editor of Artenol, a radical art journal described by the New York Times as “a cross between The New Republic and Mad Magazine.” He has produced radio and video documentaries of Michael Bloomfield and served as a consultant to Sony/Legacy on their recent Bloomfield box set.

In September, I interviewed Dann via email about his Michael Bloomfield expedition and asked why he embarked on the journey.

"‘Journey’ is an apt word! It was 10 years in the writing and probably another 5 to 7 in preparation,” volunteered Dann. “My son gave me Jan Mark Wolkin and Bill Keenom's excellent oral history on Bloomfield, If You Love These Blues, back in 2004, and I was reminded of how much I loved Michael's music. I decided I would create an online discography of all the recordings he had made or participated in over the course of his career, and the result was the first iteration of mikebloomfieldamericanmusic.com.

“Response to the site caused me to expand it, and soon I was collecting recollections from fans around the country and doing interviews with MB's friends, family members and fellow musicians. Bill Keenom then very generously sent me tapes of the interviews he did for his book and because they contained so much material that hadn't made it into IYLTB, I decided I had to write the definitive Bloomfield biography.”

What always drew him to Bloomfield’s work and catalog?

“Michael had a sound that was unlike any other guitar player of the era. It was very ‘vocal’ and instantly recognizable, to me at least, and it always moved me, much more so than that of other great players like Clapton, Johnny Winter and even Hendrix. I later became a jazz fanatic (I still am today), and it was Bloomfield who first schooled my ear in what makes a great improvisation.

“In uncovering the details of his life in music, I became increasingly aware of how remarkable a character Bloomfield was,” David offered. “Not only was he an innovator (blues-rock, psychedelic rock, brass rock) and educator (Stanford, New College and others), but he was also an amalgamator of disparate styles (folk + rock + blues + jazz + world) while being an extraordinary soloist at the same time, perhaps the first guitar virtuoso in the pop music category.”

I wondered if Dann had a theory why Bloomfield seems to be left out of so many articles about great guitar players, often overlooked and listed towards the end of any list of players.

“Yes, Bloomfield was reluctant to tour after the Flag and rejected the ‘rock star’ status conferred upon him in the late '60s. Those factors, plus his public condemnation of the music industry in general, pretty much tanked his career.

“The last ten years of his life he spent trying to avoid the limelight, and he mostly succeeded. Problems with drugs and alcohol in the last years occasionally marred those gigs he did play, and that further tarnished his star. But MB largely didn't care by that time.

“He was content to stay home and watch TV. I always say that if he too had died in that fateful year of 1970, he would be remembered right up there with Jimi, Janis and Jim. As it was, his decline was slow and inglorious, and the result was that when he passed, most music fans no longer knew who he was. That neglect continued through the '80s and '90s, and has only recently begun to be remedied.”

Born in Chicago in 1943, Mike Bloomfield learned blues guitar as a teenager hanging out in the clubs of the South Side, where he "played with every living musician who played electric blues" in real-time with masters like B.B. King, Albert King, Freddie King, Buddy Guy, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Big Joe Williams and many more from 1959 into the early 1960s.

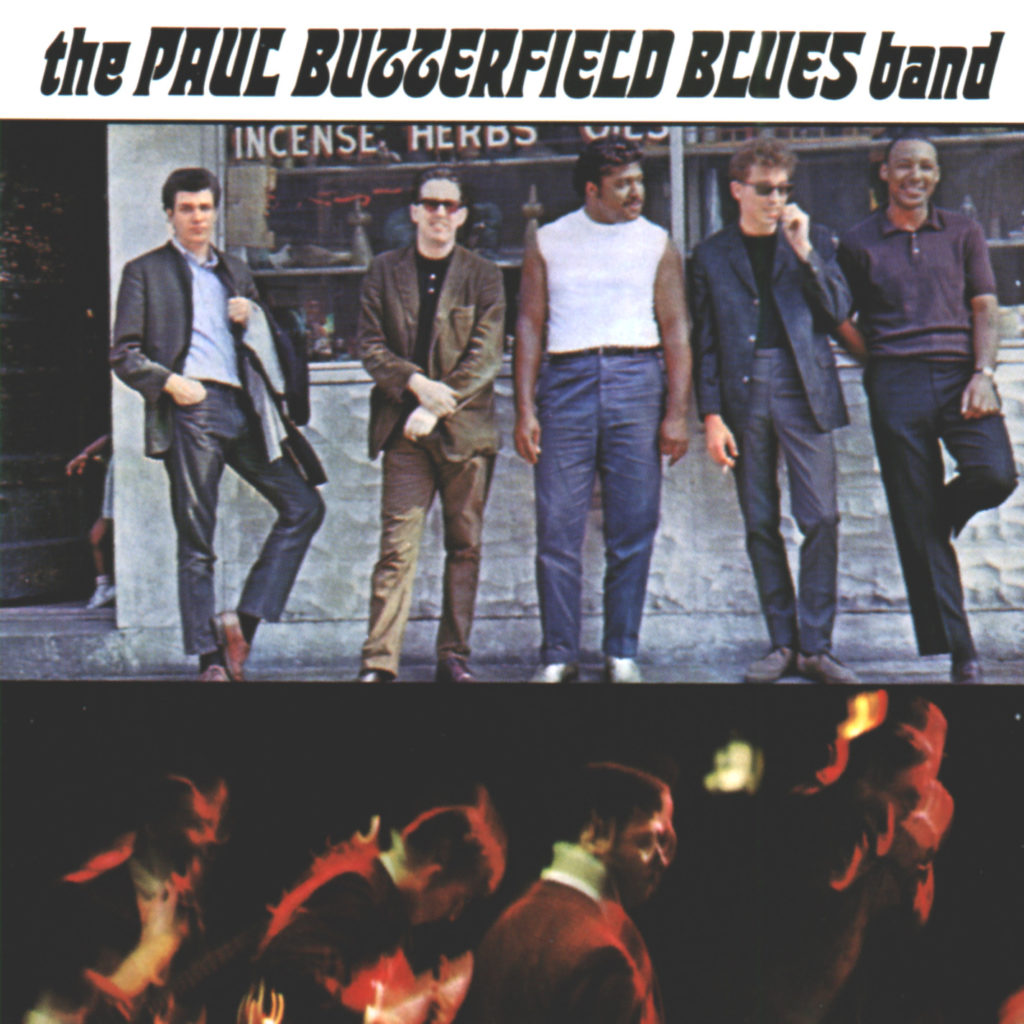

A blues artist, Bloomfield was a prodigy who assimilated jazz and a plethora of global rhythms into his fluid improvisations. As a final cog in the wheel of the original Paul Butterfield Blues Band, one of rock's first interracial bands and an example of the blue's first experimental ensembles, Michael Bloomfield helped open new vistas of cultural and musical possibilities in 1965-66.

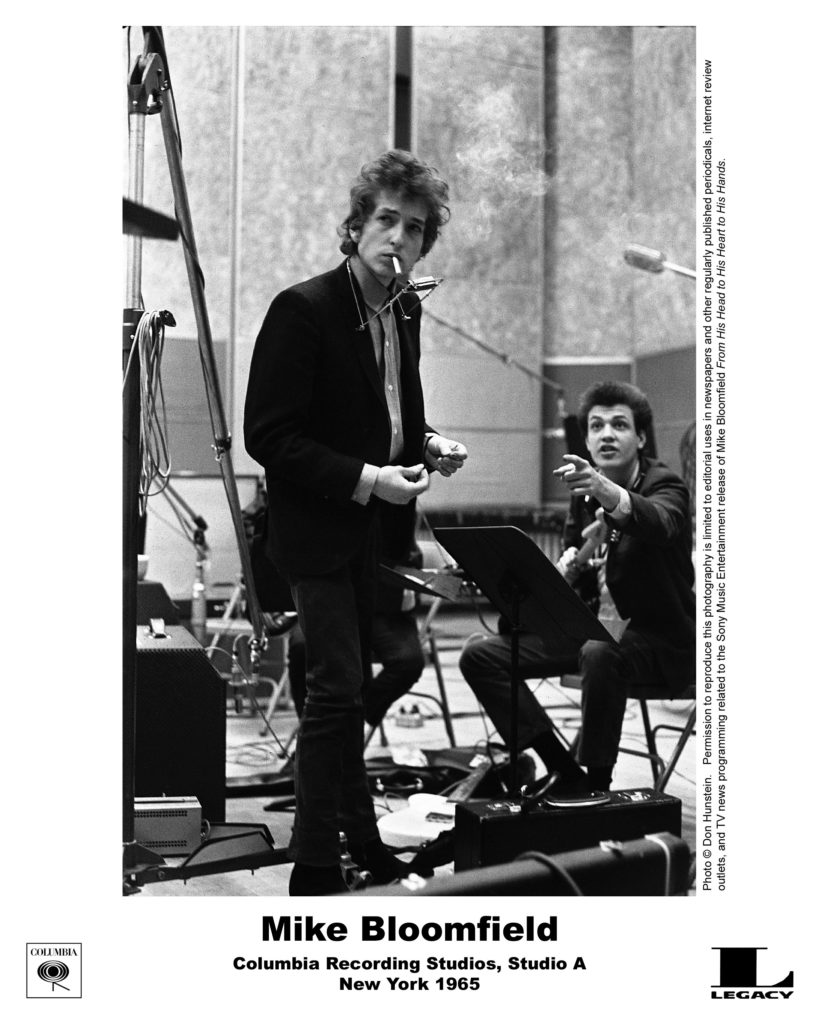

Bloomfield, who'd been signed in 1964 by legendary A&R man John Hammond, Sr., was called into duty as a session guitarist for Bob Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited album. The results, particularly the single "Like a Rolling Stone," took AM rock radio in a whole new direction.

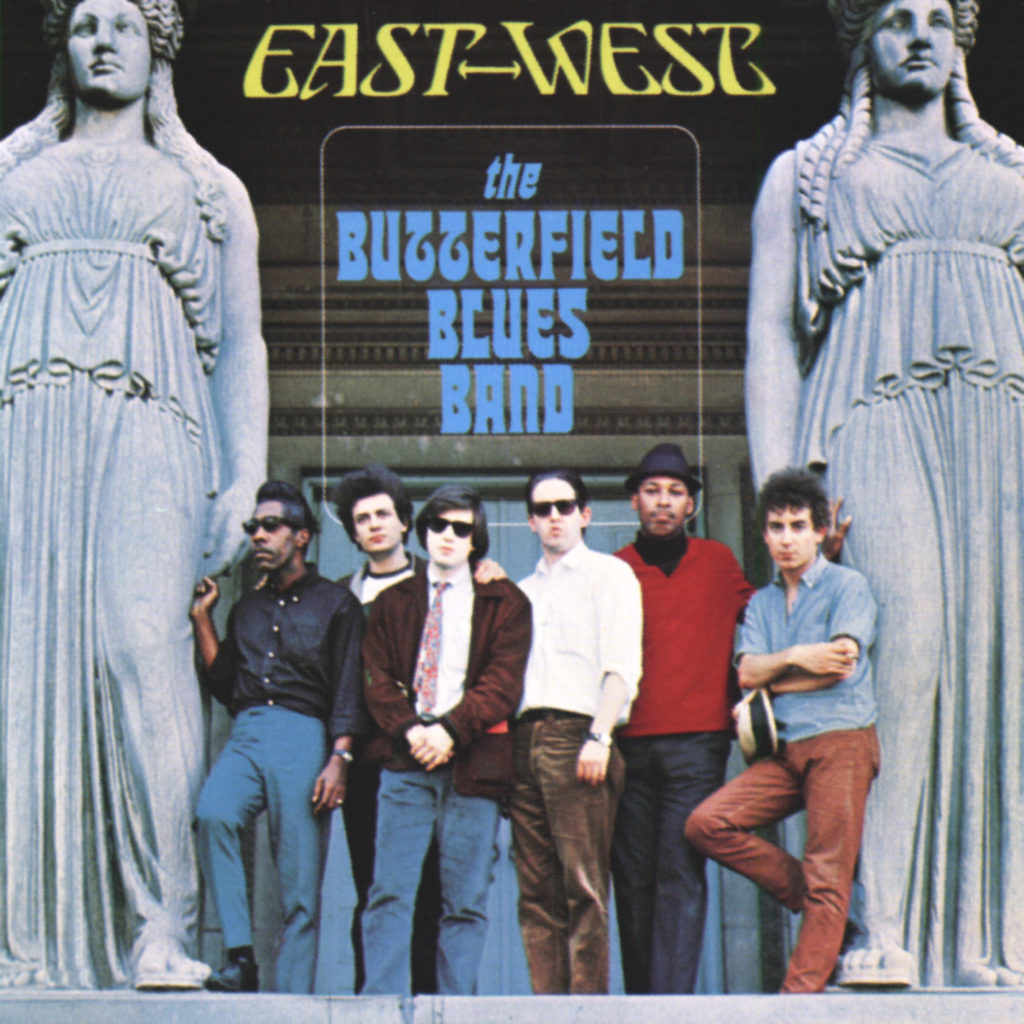

Mike Bloomfield went to work on the Butterfield Band's psychedelic blues masterpiece, East-West (1966), a landmark recording combining elements of blues, jazz, psychedelia, Eastern music and more.

In 1967, Bloomfield founded the Electric Flag, an experimental soul band with horns. He then sat in for the Grape Jam disc in Moby Grape's sophomore double album and collaborated with Al Kooper on the 1968 platinum-selling Super Session LP.

From 1968-69, Bloomfield would continue to release innovative, guitar-heavy works, including his debut solo album It's Not Killing Me and My Labors with Electric Flag member Nick Gravenites.

Bloomfield’s career was later highlighted by session work including Muddy Waters' Fathers and Sons and Janis Joplin's solo debut I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues Again Mama! as well as recorded sit-ins with Woody Herman and Tracy Nelson.

I saw the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and later Bloomfield with the Electric Flag. Their summer 1968 debut LP, A Long Time Comin’ fused R&B, jazz and rock and yielded a single, “Groovin’ Is Easy,” garnering radio rotation during 1968-1969 on many FM underground stations around America.

In 1978, I was introduced to Michael at an MCA Records reception in Universal City and interviewed him for England’s Melody Maker during his stint in the ill-fated KGB Band with Ray Kennedy and Barry Goldberg.

Besides talking about his music scoring achievements on Jim and Artie Mitchell Ulta-Kore porno films and applauding appreciative audiences for supporting the blues in Britain and Europe, yenta Bloomfield inquired “where my people were from?” I responded, “Chicago, Illinois.” He touted various restaurants like “Batts Jewish Delicatessen in the New Michigan Hotel across from the Chess offices at 2120 S. Michigan Ave.”

Michael also stressed an important lesson in our conversation, “the big thing that I learned from Paul Butterfield was not to have any fear by watching Paul go further into the deepest sections of South Side Chicago world to see and play with the immortal bluesmen.”

I mentioned to my stockbroker father, Marshall, that I just met and interviewed Michael Bloomfield, he answered, “Michael Bloomfield’s mother Dorothy [Shinderman] was just in the office this afternoon. Did her son ever play with Julie London?”

Over the last half-century, I would talk to musicians and friends about Bloomfield.

“In 1959 I was playing in Hollywood on Sunset Blvd at The Sea Witch club backing Wesley Reynolds and cut ‘Shut Down’ on the Dollar label, a subsidiary of 4 Star Records,” Larry Taylor reminisced in a 2008 interview we did. “Bloomfield told me that when he was a teenager he went to some club in Chicago after I played with Wesley, heard him in 1962, ’63, and that’s when he bought a guitar.

“Canned Heat played a gig with Paul Butterfield Blues Band at The Troubadour and I saw Michael there. 1966. I knew him when he and the Butterfield Band were staying in Los Feliz. I went over there with Elliot Ingber one time.

“I kind of became friends with Bloomfield in 1967 at the Monterey International Pop Festival. Canned Heat was on the blues afternoon with Michael and his Michael Bloomfield Thing, which was Electric Flag. We had some things in common.”

In 2010 I did a series of interviews with blues advocate Marshall Chess, whose father Leonard Chess and his uncle Phil Chess gave the world Chess Records. Lifelong record man Marshall from 1970-1978 was President of Rolling Stones Records.

“Being around the Chess artists and when I was in high school I definitely picked up fashion and music habits that were definitely different. Sonny Boy Williamson and Muddy Waters went to my Bar Mitzvah. A lot of black people were there, which was very unusual back then in 1955.

“We made enough money when I was age 14, in 1956, that’s when money really started to roll in, enough for us to move out of the lower-middle-class walk up.

“The first apartment was on the edge of the black neighborhood. Then we moved to a house in a very middle-class neighborhood that was also within three blocks of the black neighborhood. Then, in the late '50s, we moved to the suburbs. I got a brand new bike! Then it was all white people.

“Michael Bloomfield was in my high school. He was from a really rich Jewish family. He lived on a lake in a mansion. He was younger than me and knew who I was. He knew Chess Records even then. I was wearing pants without a zipper. I remember. I got that from these black guys, this kind of fashion. When I was 13 I had a custom made suit from Maxie the Tailor in the ghetto. I was sharp as a tack. Powder blue suit, blue swede shoes, black stitching down the side of the pants. I was into that big time.

“Michael ran up to me and said, ‘You look weird. Where’s the zipper on your pants?’ Then he introduced himself to me and I actually went to his house. Even then he had the same guitar as B.B. King. His family had money but I brought him a bottleneck slide guitar from Chess studio. They were always lying around. He was blown away. We actually became friends and I knew him until the day he died,” sighed Marshall.

“I missed signing all those guys in Chicago like Michael Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield. They were signed right under me. Because we didn’t think they were good enough, you know. We didn’t catch that first wave of that ripe blues movement with America. We only saw it from the UK.

“Muddy liked to drink. Muddy on stage and in the studio was the best. He was organized. He was a fuckin’ leader. I always say this. People say ‘what do you mean?’ He was a fuckin’ leader. Muddy was the reincarnation of a tribal chief, of a president, of a King and such a powerful presence. I just loved him. And he treated me so good. He used to call me his white grandson. His wife Geneva used to send me fried chicken wrapped in foil.

“Muddy once wrote a poem to a girl for me that I gave her when I was in high school. I always say this and people laugh but most of what I discussed with these guys was about sex. That was the main thing on their mind. Look at their lyrics,” Marshall summarized.

“It was a big boost when the English groups earlier covered the music on records and at their shows. We loved it and something we thought could never happen. Muddy Waters and B.B. King really dug white people doin’ their stuff. Sonny Boy Williamson was very much into white people doin’ his stuff. So was Howlin’ Wolf,” emphasized Marshall.

“Bill Graham the promoter was the greatest for the blues artists of that era, B.B. King and Chuck Berry on his bills. FM radio was a godsend for the blues. The big commercial AM stations would not play the records at all except some black stations. And I decided to repackage Chess to that market that was getting stoned and going deep.

“We saw the white audience that embraced the Chess blues artists. My father and uncle laid it on me to expand to the white market. And that’s when I did all those albums like Fathers and Sons with Muddy Waters, Otis Spann, Sam Lay, Bloomfield, Butterfield, Buddy Miles and Donald ‘Duck’ Dunn. All the various record labels cooperated.”

Bloomfield and Butterfield initially had come to Marshall’s house when they were doing a charity concert in Chicago and then suggested doing an album with Muddy Waters. Producer on the sessions was Norman Dayron. Live songs were culled from an April 24, 1969 concert and three studio sessions on April 21-23, ‘69.

“I’ve always loved Electric Mud and have been defending it from day one. I produced it. I recorded it and promoted it. At that time I was very aware and very on top of alternative FM radio stations. I drove across the United States, visiting FM deejays like Tom Donahue and Bobby Mitchell in San Francisco. You could go right into the control room and they’d put your albums right on! They’d talk to you and smoke joints right on the air! I’d meet all the DJ’s at radio stations in L.A. like KMET-FM and KPPC-FM and meet all these people.”

In 2007, I discussed Bloomfield with Bruce Springsteen and E Street Band guitarist and multi-tasker Steven Van Zandt, who, as a deejay on his Sirius XM Little Steven’s Underground Garage channel, has programmed Bloomfield’s work with Bob Dylan.

“I talk a lot about Bloomfield on the radio. Oh my God…One of the greats, the single most unsung guitar hero. Really, right there alongside the holy trinity of (Eric) Clapton, (Jeff) Beck and (Jimmy) Page. Probably next in line, as far as influence and importance would be Mike Bloomfield in our early youth growing up. Extremely important.”

“I loved Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited album. I loved Michael Bloomfield’s guitar playing on that album and loved Bloomfield on the first Paul Butterfield Blues Band album,” exclaimed Robby Krieger of the Doors.

“Bloomfield was my favorite for a while. To me, he was the first white guy who could play blues better than the black guy. I liked East-West, the second Butterfield band LP, but the first one, oh my God…I wore the grooves out. He could play harmonica and I got to know him later in life. I was really excited when we signed to Elektra and Paul Rothchild was going to produce our first album and he had produced Paul Butterfield.”

“The first time I ever felt absolutely thrilled by a piece of music—thrilled in that way that includes physical fright, even to the point of trembling—I was 12 years old and Michael Bloomfield’s guitar was responsible,” acknowledged Dr. James Cushing a deejay on KEBF-FM in Morro Bay, California.

“After each chorus of ‘Tombstone Blues’ on Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, a sound as snarling and heedless and courageous as anything I could imagine leapt out of the speaker and implied a whole world where adult men and women fought hard for their lives and died anyway. Not just implied it – proved it. And what thrilled and scared me was the way the music showed me that, even as a boy, I lived in this world, and had to affirm it to survive in it. I had no idea how I was going to affirm it. I only knew that every record this Michael Bloomfield guy played on was potentially a piece of this thrilling wisdom,” Cushing underscored.

“Over time, I would find new iterations of this wild thrill. The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, East-West, A Long Time Comin’, Super Session, The Live Adventures, and various bootlegs all filled in more of the Bloomfield picture. I learned about his insomnia and druggy attempts to cure it, his personal irresponsibility, and his surreal background as the son of the man who got rich by inventing the salt shaker. I learned about Charlie Parker and Bix Beiderbecke, and recognized Bloomfield as a man in that tragic pattern, artists overcome by the terrible demands of a musical gift that was bigger than their ability to handle it.

“Most of all I learned about the blues, the simplest but most nuanced of American musical forms because Michael Bloomfield WAS the blues. Like the music, he transcended race and background to embody the old America’s deepest invention, and its quiet, noble message: that life is suffering and ends in death, and we have no choice but to affirm it. The thrill in Michael Bloomfield’s music lies in knowing it understands all the dark places in the life it affirms.”

The Other Side of the Mirror: Bob Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival is a 2007 documentary directed by Oscar-winner Murray Lerner (From Mao to Mozart in China) about Dylan’s 1963-1965 appearances at the Newport Folk Festival, including Dylan’s pre-meditated controversial ‘65 electric set with Michael Bloomfield, Al Kooper Barry Goldberg, Jerome Arnold and Sam Lay at the venue’s soundcheck and on stage.

“Dylan 1963-1965 music was colorful, powerful, and confrontational in a way, and with a tendency towards the mythic,” Murray Lerner enthused to me in a 2009 interview.

“The live footage of ‘Maggie’s Farm’ was so powerful and jolting to see in a theater. With the camera, daring it to love him, he is being confrontational with the audience. There was an audience involvement in this thing and there was a message of the audience that they were putting out.

“With Dylan moving from an acoustic setting to electric I felt that electricity was needed to distribute the music in a wide basis, radio and television. Then once it happened the hunger for the feeling that electricity gave people listening to it was more than volume. I think electric music gets into your body and enters into your nerves quite deeply, and almost puts you into a trance,” reinforced Lerner.

“It’s hypnotic. I’ve always felt this and that was the feeling I had when I watched Bob. And I was excited by it. I not only appreciated the changes I loved it! I really was mesmerized and hypnotized by ‘Maggie’s Farm’ and ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ on many levels.

‘I knew it was a gateway to a new culture in the form of based on the older culture, and I thought this was it. I was mesmerized by electric music and when Dylan went electric it got into your bones.

“In my movie Festival, Mike Bloomfield talks about Butterfield. I wanted to show that this was a movement for white kids and white people to get into the blues. They were iconic figures in my mind.”

“There was more to Bloomfield than energy,” stated writer Kirk Silsbee. “Tremendous vocabulary. Tremendous grounding in the blues. He wasn’t just riffing out of his head playing mindlessly. Mike had great feeling for the blues in all of its forms.

“The rhythm section of drummer Sam Lay and Jerome Arnold on bass that may be the A lineup for the Paul Butterfield Blues Band rhythm section. Sam Lay was the greatest of the youngest Chicago blues drummers. Jerome Arnold on the first two Butterfield albums was an economic player.

“There were some electric guitarists at Newport like Pops Staples, Howlin’ Wolf’s band. In the minds of so many of these folkies, and there is no purist like a folkie purist, and this Dylan episode, over 50 years later, still talking about it, just proves that out.”

Al Kooper wrote in his book Backstage Passes & Backstabbing Bastards, “If there ever was a galvanizing moment in musical history, this was it. The more coherent members of the audience were the ones with tears in their eyes-not Bob. They realized that things might never be the same again, and it was a rude awakening standing there amidst the crowd at Newport. But the media misconstrued (or manipulated) the whole point. They attributed the booing to Dylan’s electric appearance. Hell, Butterfield played electric the day before, and the Chambers Brothers played electric earlier in the show. Bob wasn’t trailblazing a plugged-in performance on that stage.”

Still, Dylan’s well-documented ’65 Newport appearance has somehow attained now mythic status so we should expect a filmmaker and lead male star actor to re-create the event for cable television viewers and/or art house cinema patrons.

“In 1965 I interviewed Butterfield and he then played Massey Hall in Toronto on a Sunday night,” recalled Canadian-based writer Larry LeBlanc.

“I knew all about Butterfield via Jim Delehant in Hit Parader who wrote continually about him. So they play the Massey hall show. Paul asks me where can we go for a drink. Toronto is closed down for liquor on Sunday night. Except for a few tourist designated areas. Sorta bullshit but there were a few.

“I knew one the Palm Grove Lounge. So Butters, Mike Bloomfield and organist Mark Naftalin grab a cab. At the club it’s a $5.00 charge. Paul pays for all. Performing is Chubby Checker. I kid you not. Mid-sized crowd in suits and ties. We are all in hippie type clothing. Chubby is fucking incredible. We get nicely inebriated. Fun fucking evening. I worshiped Paul who could scare reporters. Not me. He was great. I was about 21 and I knew the blues. He was gracious and respectful. God bless anyone who messed with him though.”

“Well, Michael and I met on the Dylan ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ session,” songwriter and record producer Al Kooper said to me in a 2007 interview. “I had read about him in Sing Out magazine, and saw a picture of him where he looked a little more rotund then he was when I met him. His brother says he was a fat kid growing up. So we met on the ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ session and really hit it off. So we played together on that.

“I was supposed to play guitar on that record. I packed up my guitar when I heard him warming up. It never occurred to me that somebody my age, and my religion could play the guitar like that. That was only reserved for other people. It never even occurred to me that that was an option for someone my age and my color. I had never seen that, or heard that up to that day. And, you know, I ended up playing organ on that record, and then I became a keyboard player really that day. So, it was a damn good thing because, you know, that was competition I couldn’t deal with.

“Tom Wilson was sort of a spectator sport producer. He didn’t do all that much. He’d put you in the studio and got the job done. He didn’t interfere in anything, at least when I worked with him.

“Tom earlier worked for Savoy Records. He was a very bright guy and he talked about very erudite things, and he really saved my life that day on that Dylan ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ session.

“Because he could have…I went to him and said, ‘Man, let me play the organ.’ They had just moved Paul Griffin from the organ to the piano. And I went over to Tom Wilson, and I was invited just to watch, you know, and I said, ‘Man, why don’t you let me play the organ, I got a great part for this,’ which was bull shit. I had nothing. And he said, Man…You’re not an organ player…’ And then they came to him and said, ‘phone call for you Tom.’ And he just went and got the phone. And I went in to the studio and sat down at the organ. He didn’t say no. He just said I wasn’t an organ player. OK.

“On the Highway 61 Interactive CD put out a few years ago, they have the multiple takes of ‘Like a Rolling Stone,’ and on there you can hear Tom Wilson, ‘OK. This is take 7. Hey! What are you doing in there?’ Then you hear me laughing, and that was the moment he could have just thrown me out and rightfully so. And you know what? He didn’t. And that was it. That was the beginning of my career, right then and there. That studio dialog is documented. Wilson is the guy who invited me to the session first of all, which is really nice. You didn’t get invited to Bob Dylan sessions, you know, especially if you were a nobody like I was. And there it was. There was the chance he had to toss me, and it would have reflected back on him because he had invited me to the session.

“I was waiting to see what chord they were going to do. There was no music or lead sheet, or anything. I was just playing by ear and I didn’t want to be the one making a mistake because I was doin’ like a rebel run there. But anyway, we played together on that session, and the rest of the (Highway 61 Revisited) album.

“I got to know Bloomfield in 1965 and ’66 in New York. I joined the Blues Project. He was in Paul Butterfield’s band. Two blues bands. And we both left the blues bands to start horn bands, which we were both kicked out of again. The horn bands that we started. Very amazing parallel in our careers. Starting from the day that we met. So it seemed to me, in hindsight, looking at that, when I started producing at CBS, that we should make a record together. We were like destined to do something together. Now this whole time we had been friends since we met. I’d go visit him when I was in his town.

“In 1967 at the Monterey International Pop Festival I thought the Mike Bloomfield Thing [Electric Flag] was very exciting. I was very happy for him. I thought Buddy Miles was amazing then. And I was in the wings when they came off. Buddy Miles was crying. All 17 years of him. I saw Butterfield’s set and I thought it was great and he was using horns for the first time in front of a lot of people.

“Michael ended my guitar playing I’m tellin’ ya. Both of us had just played on that Grape Jam album. So that sort of gave me the inspiration to say, ‘Why don’t we make a record.’ I wanted to make a record with Bloomfield, and I wanted to make a record that was a very simple, basic record, not a ‘weighty’ record. We were both on the Grape Jam thing, I said, ‘let’s make a rock ‘n’ roll record based on the way jazz records are made. You pick a leader, or two leaders, and then you just go in, you pick some songs, you pick sidemen, and you just blow. No rehearsing or anything. You just go in and blow.’ So I said ‘I don’t want to make a jazz record.’ And I was very dissatisfied with the way he was recorded up to that point.

“His live playing was like 300 times better than performance on a record to that point, in my opinion. So, what I wanted to do was put him in a situation where he was uncluttered by his career and uncluttered by his situation in the recording studio, which must have inhibited him.

“So I made it as uncomplicated as possible for him. Because that was the goal of the sessions for me, was to get amazing playing out of him like I heard him do on stage. And I felt really vindicated that I had done that. And that’s what I wanted. I did what I set out to do,” boasted Kooper.

“And, the other thing was, we both had been kicked out of the bands, and then Stills, too. He was out of his band (Buffalo Springfield). So Stills fit in, in a really weird way. Because none of us had anything at stake and that was the whole point of that record. There was no career thing goin’ on. We just did it because we played music. That’s what’s so wonderful about that. Super Session wasn’t made to sell records. It was just made like those jazz records were made for Blue Note, except it wasn’t ‘Blue Note’ kind of music.

“I had no expectations for that record. I mean just none whatsoever. I just did it because I had a job as a producer and I had no one to produce, and I went in because I thought Michael and I should make a record together, because how our careers were parallel. And also because we were friends and it would be fun to work together. Michael brought Eddie Hoh (drummer) in, and I brought Harvey Brooks in (bass). I said ‘you pick the drummer. I’ll pick the bass player.’ Again, sort of like a Blue Note concept.

“The most important thing is the playing of the two principals, Bloomfield and Stills. It’s timeless. Bloomfield’s stuff is some of the greatest blues playing that there ever was.

“Because it was a great period of time and there were great minds working geographically located in the same place. There was a lot of freedom out on the West Coast, but frankly, Super Session could have been recorded anywhere.

“I was in Los Angeles the day Super Session was released and we really didn’t expect anything from that. We didn’t think that was a commercial record. It was my opportunity to get great playing out of Mike in the studio which nobody else really got.

“I went into a record store and they were selling them all over the counter. ‘I can’t believe this,’ because we had no expectations.”

“The dynamic impairment goes to the idea that these sessions were very spontaneous and very open,” added Dr. James Cushing. “I think it's having been recorded in L.A. is kind of an anomaly given Koop's New York cred, Bloomfield's Chicago cry and the loose jazz-jam feeling I associate more with Greenwich Village than with Hollywood... popular music strictures or a sense of what was going to be commercial.

“It is also a blueprint in some ways of the path the new FM radio was going. Kooper and his Super Session, was not, music about expressing rebellion against conventional society. This was music that was meant to be a part of a new way of living. This music assumed that the revolution had been fought and won. And that now we could enjoy the fruits of the revolution. Which was the freedom to hear really gifted musicians jam without any obligations to fit into popular music strictures or a sense of what was going to be commercial,” he concluded.

Kooper once penned a tune “They Don’t Make ‘Em Like That Anymore” about Bloomfield.

“It doesn’t say Michael in the lyric or anything like that, but he inspired me to write that song, and his death inspired me to write that song. It just was a way of expressing the loss. That’s all. ‘Cause it’s a big loss in my life.”

The 1969 double album, The Live Adventures of Bloomfield and Kooper cut in September 1968 at the Fillmore West, showcases Kooper and Bloomfield at their best, especially on “Mary Ann,” a Ray Charles song and Albert King’s composition, “Don’t Throw Your Love On Me So Strong.” John Kahn (bass) and Skip Prokop (drums) were on the date.

Carlos Santana made his Columbia Records debut guesting on “Sonny Boy Williamson.” The cover art is a painting of Bloomfield and Kooper by Norman Rockwell.

“Al Kooper had spotted my band the Paupers at The Café A Go Go,” cited drummer Skip Prokop in a 2012 interview we had. “We would jam and hang out as friends and buddies in New York and he would actually play on the second Paupers’ album.

“We were at Monterey. Al was working as the assistant stage manager at the Monterey International Pop Festival and played a short set and I saw him. Al and Mike Bloomfield then wanted me to be on their Live Adventures album in San Francisco at the Fillmore.”

“Well, you know, that was a weird record,” laughed Al. “We sort of did that because people gave us some shit about the confines of the studio, and it was slick, this kind of thing. So I said, ‘let’s go down and dirty and play a gig and record it live. Nobody is gonna yell studio at us for that.’ So that’s what we did. And it actually was a little too down and dirty (laughs).”

In 2014, Legacy Recordings, the catalog division of Sony Music Entertainment issued From His Head To His Heart To His Hands, a career-spanning 3CD/1DVD box set anthology chronicling the music of Michael Bloomfield.

The label’s media announcement promoted endorsements from Bob Dylan, “Best guitar player I ever heard,” Eric Clapton, “Mike Bloomfield is music on two legs,” and Dave Alvin, “The future of rock guitar was in East-West. At one point or another you're hearing what would become the Grateful Dead, Santana, the Allman Brothers, Crazy Horse, Television and the Tedeschi Trucks Band."

Produced and curated by Al Kooper, From His Head to His Heart to His Hands contains a wealth of previously unreleased tracks—including Bloomfield's first demos for John Hammond Sr.in 1964 and his final public performance, concluding with a track from the 1980 Bob Dylan concert in San Francisco—alongside essential key recordings, both live and studio, from his all-too-brief life and career. The anthology collates solo material, work with ensembles including the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and the Electric Flag, tracks with Muddy Waters and Janis Joplin, Highway 61 band outtakes and more.

The box includes a 40-page booklet displaying a gallery of photos covering the various phases of Mike's extraordinary career and extensive liner notes by music journalist and musician Michael Simmons.

“I became a Bloomfield fan when I was a 10-year old Beatlemaniac in 1965 and my best friend's 16-year old brother played us the first Butterfield album with Michael on lead guitar,” remembered Simmons.

“I was astonished by his fleet fingers, his ringin'-a-bell tone, his ferocious attack. I dug Electric Flag's debut, but it was Super Session with Michael and Al Kooper that sent me over the top. The A-side of that album with Bloomers is still one of my fave rock recordings of all time. It's got chops, improvisation, intelligence, soul -- things I've found lacking in a lotta rock for the last 40 years.

“I spent about 8 months researching and writing the liner notes for the box set -- only three months past the deadline! -- during which time I fully immersed in Bloomfieldiana and interviewed dozens of family, friends, musicians and archivists.

“Like all genii, Michael was one-of-a-kind. Several friends call him the most intelligent person they've ever known, he was completely committed to making music for art's sake and not for commerce, and he thought for himself. He was hysterically funny, generous to a fault, human and imperfect and undependable and a fantasist, and the first guitar god of '60s rock. While he influenced every rock and blues guitarist who followed, no one sounds exactly like him and I can't say that about many of his peers. Plus he was a nice Jewish boy, which warms the pastrami of my Yiddishe heart.”

On this 2014 Mike Bloomfield compilation, Al Kooper assembled a different mix of “Like a Rolling Stone.”

“I took Dylan’s voice off the master tape and put the backing track on and re-mixed it,” revealed Kooper in a 2014 interview we conducted.

“You know, in ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ there are three things that I made louder than they were: The piano, because that guy, (Paul Griffin) was so brilliant. So the piano is louder in the parts that he plays amazing things. And the thing that is really eye-opening about it is the drums are louder. And you hear some things you’ve never heard before.

“Besides Michael’s playing you can really hear the drums of Bobby Gregg. I had all the tapes transferred to digital. I didn’t want to touch those tapes.”

The collection houses Sweet Blues: A Film about Michael Bloomfield directed by veteran music documentary-maker, Bob Sarles.

From His Head to His Heart to His Hands Sweet Blues: A Film about Michael Bloomfield documentary combines vintage audio interviews and live performance footage of Bloomfield with newly lensed commentary on Bloomfield from the guitarist's friends and fellow musicians.

I never met the Bloomfield,” mused Bob Sarles in our 2019 interaction.

“One time I went to see him perform at a club in San Francisco, shortly after moving there in 1980. He was a no show, which was not uncommon at that point of his career. But, even so, Michael Bloomfield has had a tremendous impact on my professional and personal life.

“When I was in high school in the early ‘70s a friend of mine turned me on to Super Session LP. It was the Bloomfield side that attracted me. I thought the playing was sublime, and I became a huge fan of everything Bloomfield had ever recorded, particularly on the first two Butterfield albums, that first Electric Flag album and of course Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited.

“Just about anything the man played was of interest to me: even the less regarded discs he made with Norman Dayron for Takoma and the soundtracks to porno films he made for the Mitchell Brothers. There was something about the way that he played that was like no other. Bloomfield just blew me away.

“In the late ‘80s, a few years after his untimely death in 1981, I decided that there needed to be a documentary film made about Michael. Since no one else seemed to have any interest in taking on this project, I made the first steps in attempting to make the film myself. At the time, I was working as a freelance film and television editor, but had little professional experience as a documentary film director. I gained that experience as I worked on the Bloomfield film.

“The first people who agreed to be interviewed for my film were Carlos Santana and B.B. King. Not knowing how to begin, I called Columbia Records, then still Carlos’ record company. They sent me Santana’s publicist, who told me in no uncertain terms that it was Carlos was booked on tours and recording sessions for the next two years and to not hold my breath. I asked them to please just pass on the request.

“The next day my phone rang. ‘Is this the guy making the film about Mike Bloomfield?’ a voice asked. It was Carlos, calling me directly, saying this was a film that needed to be made and he would be available. I just needed to tell him when and where and he'd be there. B.B. King was also most gracious, happy to lend his considerable cache to the project.

“Michael’s story is the story of the blues torch being passed from the great blues men of post WW2 Chicago to the generation of white kids who worshipped them and made pilgrimages to the South side clubs like Peppers and Sylvio’s to witness and befriend their music heroes.

“It’s the story of someone who rejected the mantel of ‘Guitar God’ and the trappings of rock stardom. It was the story of a kid who rejected the security of a successful family business to live the life of a blues man. It took me over twenty years to get Nick Gravenites, an essential voice to telling the story, to sit down with me.

“Years went by and I collected my materials and interviews for my Bloomfield film. I established a career as a music documentarian, doing work for television, home video and major music museums including the Rock Hall in Cleveland Ohio and the Stax Museum in Memphis Tennessee. But, the Bloomfield film became my albatross, unfinished due to my inability to raise the money needed to complete the project,” Bob lamented.

“Then one day Al Kooper called me up and said he was readying a Bloomfield boxed set for the Sony Legacy label, and that perhaps I could use some of my interviews to put together some content to be included on a DVD included in the box.

“I jumped at the opportunity and fashioned a 60 minute version of my documentary that I hoped Sony would be able to clear the music, archival footage and photos. After some negotiations Sony agreed and finally the project would be available for fans to enjoy. I’m forever grateful to Kooper and Sony for allowing that to happen.

“Early on while working on the Bloomfield film I had a vivid dream. In it Mike came to me and he was not happy about my efforts. He confronted me and said, ‘Why are you making a film about me, man? I’m just a white guy covering the blues. You need to make a film about the real deal: Muddy, Wolf, Sunnyland Slim, Otis Rush, Magic Sam. Those cats. I’m just a facsimile, man.’

“In my dream I argued back, ‘No Michael, you are the lynch pin, the connection to those artists. Without you the flame would have been extinguished. You kept it going. You need to be remembered.’ In my dream Bloomfield was not satisfied with my argument.

“I woke up upset, and when the sun came up I called Michael’s brother Allen to tell him about my dream. ‘That was no dream,’ Allen said to me. ‘That was a visit from my brother Michael. He was talking to you. That was him.’

“Michael was the greatest, and he should be remembered,” testified Sarles.

“I had gotten together with Michael through Mitch Ryder sessions in New York,” keyboardist and songwriter Barry Goldberg recollected. “All the Detroit Wheels plus me on piano. I introduced Michael to Mitch and he’s on ‘What Now My Love.’

“In July ’65 I played piano with Bob Dylan at Newport in 1965 and Michael was there, too. I met Dylan the night before with Bloomfield and he asked me to play with him. The night before we played Newport we all rehearsed at a big mansion in the area with a view of the ocean. ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ was already on the AM radio.

“No one was prepared to record electric music then. No one really knew yet what amplified music at a big concert was yet. That was a whole craziness. And, even then it was a beginning, a pioneering move, and no one knew the power of amplified music up until the Monterey International Pop Festival when I was in the Electric Flag with Michael.

“I always loved Michael’s guitar playing. Michael learned and played with the intensity and shook a string back in Chicago as good as Otis Rush, or anybody I had ever heard. I was really a fan of Michael back in high school. We had rival rock ‘n’ roll bands,” boasted keyboardist Barry Goldberg.

“The role for my keyboards with Dylan at Newport, or later with Michael at Monterey in ‘67 was a support role. And I was very content in just laying down the sound in the background and having those great virtuoso soloists coming at me. I just enjoyed listening to Michael.

“The Electric Flag rehearsals were a couple of gigs at the Fillmore where we opened up for Cream. I talked to Brian Jones for about a half an hour at Monterey. He knew Paul Butterfield, and I think had seen Michael when he was with Butterfield in 1965, or ’66 when Butterfield played in London.

“At Monterey, after our set, it was a relief. We were received so well because nobody knew what was gonna happen. That was a big deal because we could have blown it. But we came through. Clive Davis signed us. We recorded ‘Groovin’ Is Easy’ afterwards and Mama Cass sang on it.

“In 1966 I was at the Café A Go Go in New York when Chas Chandler discovered Jimi Hendrix. Chas was with Eric Burdon. I was playing with John Hammond when Hendrix was playing with us for the whole week and did ‘Hey Joe.’ That changed his whole trip.

“Then at Monterey I saw Jimi, and he called over to me, ‘Hey Piano Man,’ that’s what he called me ‘What’s happening?’ ‘You are!’ I remember that like it was yesterday.

“Shortly afterwards I wrote a tribute song with Michael Bloomfield about Hendrix, ‘Jimi the Fox’ and we did it on our album Two Jews Blues. Later, when Jimi and Buddy Miles did Band of Gypsys, Jimi told Buddy how much he really liked our song about him.”

“FM radio in 1967 blew my mind when I found it. Taking LSD and listening to Frank Zappa,” Carlos Santana proudly stated to me in a 2014 interview.

“For me, being right out of high school, and listening. And really listening, it gave me a vast awareness of ‘where do I belong in all this? And I looked at B.B. King on my left and Tito Puente on my right.’ And that was a peak on acid when I saw this. ‘You can do both. You can be both.’

"The first time I saw Michael play guitar...it literally changed my life enough for me to say, 'this is what I want to do for the rest of my life.'"

“I met Carlos in 1967,” reflected Bill Graham in a 1976 interview I did with him.

“I had the Fillmore in San Francisco and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band was playing. My office was right above the marquee. There were windows over the marquee and you had to go through that door in my office on the second floor to change the lettering. Anyway, I’m sitting in my office in the middle of the night and head some noises outside my window. I went to the window to look outside and there are two guys who climbed up a rain pipe to get to the second level to get it. It was Carlos and Michael Carabello, who was a conga player friend of his.

“They were trying to get in to see Butterfield. He told me he was Mexican and liked Latin music, and my real joy in life is Latin music. We started talking and he said he had some musicians, and I said let me hear them—and that’s how we met.”

“Booker T. and the MG’s played Monterey Pop in 1967,” specified guitarist Steve Cropper in a 2007 interview. “When we arrived I saw one band that night, a band from Canada. The Paupers. Unbelievable! They blew me away, because they had a style unlike anyone else.

“We also saw the Electric Flag. I didn’t know who I was seeing. It was like Stax, and I didn’t know until later Michael Bloomfield’s devoted love for Stax and the Staple Singers. I liked the ‘Flag that day. And we flew up there from L.A. on the plane with Paul Buttterfield. I saw his set.”

“At the Monterey Pop ’67 festival, Michael Bloomfield was awe-struck meeting Steve Cropper of Booker T.& The MG’s,” described former Atlantic Records’ executive and record producer Jerry Wexler in our 2006 chat “So he followed him around. Michael has this sort of naïve puppy love quality about him.

“I went up to Michael and his group, maybe they were the Michael Bloomfield Thing, or the Electric Flag by then, they were so good, and so I said to Michael. ‘We’d like to sign you up. This kind of music deserves to be on Atlantic.’

“Michael says ‘I’ll have to ask Albert (Grossman).’ The next day he comes up to me and says, ‘Gee Jerry, I’m sorry, we can’t sign with you because Albert says Atlantic steals from black people,’ naively quoting his manager. ‘Give Albert my thanks,’ as we had a strong reputation for good royalty payments and fair dealing. That’s not the only confrontation I had with Albert. I found him to be the most obnoxious piece of low life I had ever met in the music business.

“Later, in the early 1970s I eventually produced an album with the Electric Flag.

“All credit to Clive Davis because he grabbed up what was potential rock super sales in those groups that he signed. He was smart enough to do that. It didn’t interest me. Maybe I wasn’t smart enough to hear it. So I missed out. He put his label at the cutting edge of rock although I bid on the Electric Flag and nearly hooked one fish.

“After Monterey, I later got the rights to Woodstock. The soundtrack albums came out on Atlantic on our Cotillion label. There was a lawyer named Paul Marshall, he used to be our in-house council. But we parted ways. And he was not our lawyer anymore, but, nevertheless, he called me up, ‘Listen. Are you interested in Woodstock?’ It was going to take place in two weeks. Who the hell knew what Woodstock was going to be? He said I could have the rights for seven thousand dollars. I thought about, and bought it for seven grand. I figured seven grand? Let me take a shot. And that was it. I should have grabbed the film rights to but Warners got them. Thank God that I bought Woodstock.”

During 2007 I spoke with Clive Davis about his ’67 Monterey moment where he inked Big Brother & the Holding Company featuring Janis Joplin and the Electric Flag. Al Kooper also brought to Davis’s attention his Blood, Sweat & Tears outfit for the Columbia label in late ’67.

“I was seeing the business change,” remarked Davis. “I was seeing music change, but I was waiting for the A&R staff to lead into these changes that were showing evidence in becoming important in music. So when I really came to Monterey not knowing what to expect, but seeing a revolution before my eyes. I had no idea what awaited me.

“All of a sudden seeing Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company, and the Electric Flag, and the artists that were there, there no was no question that the predominance there was a change in contemporary music. A definite hardening, edgier, rockier amplification that was taking place that truly was signaling a major revolution in rock music. “The success of the artists I signed at Monterey gave me confidence that I had good ears.

“I had no idea I had ‘ears.’ I had no idea that I could do this. It never occurred to me that I would be doing it, and so that as each step came through it emboldened me and gave me the confidence to trust my own instincts. Monterey is a without question probably the most vivid memory from a career point of view, from an emotional point of view from a character-affecting point of view that I’ve ever had.”

“I saw the original Paul Butterfield Blues Band when we worked with Paul the one time when the Byrds really came to the plate,” ventured Byrds’ bassist and songwriter, Chris Hillman.

“Which was when we did a week at The Trip on Sunset Blvd. They were so good. Smoking. Michael Bloomfield doing answer solos with Butterfield on harmonica. The one time in our whole career that we played every night at our peak. It wasn’t a competition. It was two different kinds of music. We went ‘oh my God. We played good.’ That was when the Byrds really jelled and really got together that week at The Trip.”

“The first time I heard the Paul Butterfield Blues Band was a happy accident,” revealed record producer Denny Bruce. “I was going to see the Byrds in 1966 play at The Trip club in West Hollywood. In a nutshell, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band was the opening act, who I heard about, but hadn’t seen.

“Hearing traditional blues records, or seeing some live blues acts, usually acoustic, I wasn’t ready for hearing the electricity coming off of the stage. And I do not just mean from the amps. What a great team of players, where every guy knew his role, did his thing, and supported the others to make a sound all of their own.

“Nothing against the Byrds, who I liked, but they sounded like college guys in a dorm room playing folk songs, and one of them had a small amp. The Butterfield Band were men showing the boys how to play. The evening before the PBB did a show at the It Club in downtown L.A.

“I went down to the Golden Bear in Huntington Beach to see them play two sets the next night. I went with Jack Nitzsche, a Howlin’ Wolf fan, and from Hawaii ‘The Big Kahuna,’ a local celebrity for the great pot he sold.

“Kahuna never told us he knew the ‘Butter Band.’ So then we went to San Francisco with them and saw them rock the Fillmore. We hung out with them at Seal Rock Beach, where they liked to stay.

“I became friends with Mark Naftalin and Michael. Mark was a friend of my roommate Barry Hansen, now known as Dr. Demento. So Mark and Michael would come by while in L.A. In 1968 I started managing and producing blues acts.

“Magic Sam was from the West Side of Chicago, and was on tour. He was playing his first gig in San Francisco, opening for Johnny Winter at the Avalon.

“Michael came to the show early, and dropped in and had a nice chat with Sam, his bass player and drummer, who Michael knew. He knew just about everybody, really. As Magic Sam is getting ready to go, Michael said, ‘Sammy, just do what you do on the West Side and these hippies will love you!’

“I laughed, and thanked him, saying ‘I didn’t have a pep talk ready!’ M.B. looks at me and says ‘He knows how good he is. He is also handsome, and cocky, a lot like Sugar Ray Robinson.’

“Things went well for Magic Sam, and I had talks with Jerry Wexler, and Michael, about Michael and Nick Gravenites doimg an album for Atlantic or Stax, using all the good players in Memphis. It all was looking good. And then, at age 32 Magic Sam passed away. Dec 1, 1969.

“On February 11, 1970, promoter Bill Graham ‘gave me’ the Fillmore West to promote the Magic Sam Memorial Concert. No charge, all proceeds going into a ‘trust fund set up’ for Sam’s family.

“Michael put all of the musicians together, meaning all of his friends. Great guy. Great night.

“I moved on to being the West Coast A&R man for Vanguard Records. They never had an office on the West Coast. By now, Michael was tired of touring and always being under the pressure of keeping a band together.

“I would go visit him at his Mill Valley home. His dream gig would be if he could make music in house, and never go anywhere. He did some movie scoring and thought he could watch a movie at home and ‘score it.’ I tried to get Vanguard to let me try to start doing albums in the Bay Area - as Michael knew all of the players, and he could be like Steve Cropper, no more ‘guitar hero’ business. The East Bay was untapped at this time and there was a good R&B scene going on.

“Everything seemed to make sense, but not to Vanguard…

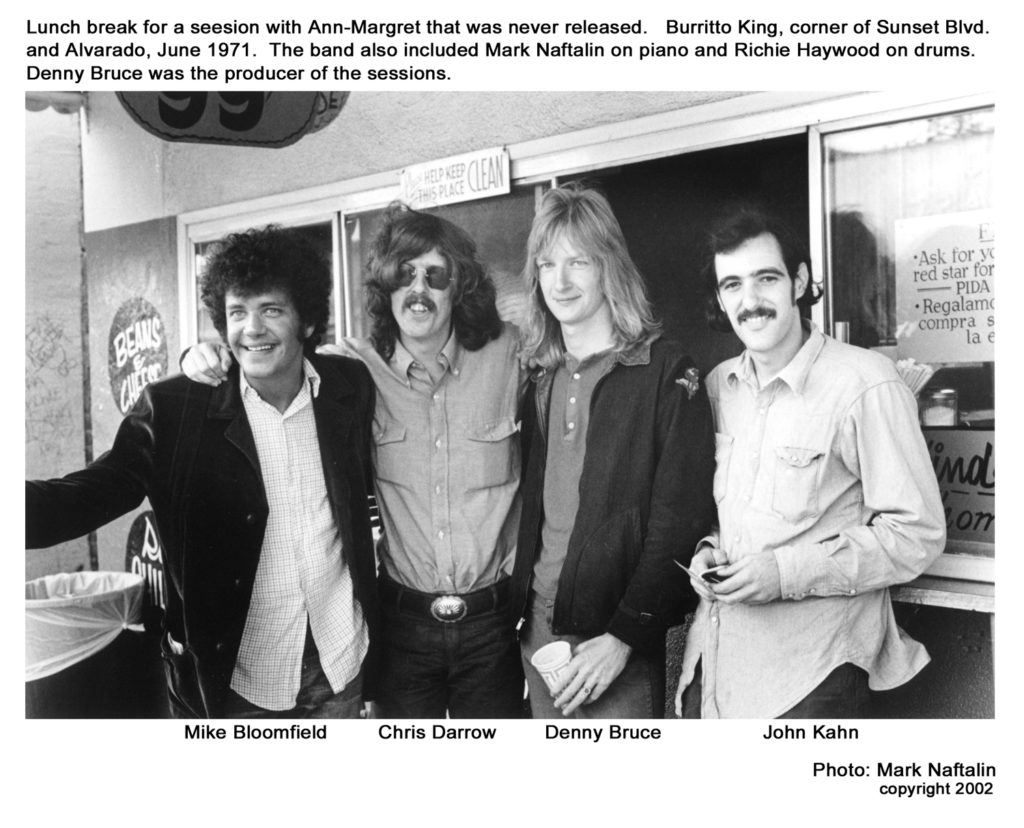

“In 1971, I met Ann-Margret’s manager, and he was hoping she could make a pop record, now that she was a hot act in ‘Vegas.’ And the manager had another female act who he described as a Vogue model, who sounded like Janis Joplin. I tell him I need to put some thought into this, after getting to meet her!

“I call ‘Bloomie’ on a whim and rundown the Ann-Margaret situation. I let him know all the musicians will get double scale. Michael got excited. He said ‘You know, we went to the same New Trier High School in Glencoe, Illinois. Man, this sounds great.’

“Everybody had a good time. The ‘model’ was just so-so, but the band loved what they were playing.” (Neither of these acts got a record deal…)

“Several years later I got into a partnership with Chrysalis Records. They bought the Takoma Label, and I was the President. Michael already did one album for Takoma, and knew and liked how the company worked. No pressure at all on the artist. Record when you feel like it. He wanted to do a quiet, solo show in a small club, doing all acoustic guitars and some piano songs. So no problem.

“Bloomfield is booked at McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica, which maybe holds a couple of hundred seats and folding chairs. Nice room for a solo act, like a singer/songwriter. A few mikes, a tape machine. He is still in Mill Valley. I call him the day before the gig to see what time he will coming down. His answer was he would be coming with Mark Naftalin, so I need a piano for him. He already has hooked up with a drummer and bass player who live in LA….

“I said ‘I thought you wanted to do a solo album?’ He replied, ‘I have trouble telling friends they can’t play on this gig.’

“Just fitting this gear on the stage took skill, planning, and patience. I’m glad we did two sets as we did get a good album out of it. I’m With You Always is issued on the Benchmark Recordings label. It is available on-line. A handful of these tracks are on From His Head To His Heart To His Hands.”

“I first met Mike Bloomfield in the summer of 1971,” the Kaleidoscope’s Chris Darrow reminded me in a 2019 dialogue.

“My friend Denny Bruce had been selected to produce three cuts for Ann-Margret, who was searching for a record deal. I was brought into the project as music director, with Denny acting as producer.

“The band Denny chose for the recordings was a great one, which included Mike Bloomfield on guitar, John Kahn, bass, Mark Naftalin on keyboards, Richie Hayward, drums, Lowell George on slide guitar and me on acoustic guitar. We all had a chance to hang around together for a couple of days.

“That’s when I got a chance to get to know Mike, as well as playing with him and the rest of the crew while recording in the studio. I had seen the Paul Butterfield Band live a number of times, so I was familiar with Mike’s playing, both live, as well as on his many recorded tracks. He was an effortless player and a really nice guy as well.

“Due to his Chicago upbringing,” continued Darrow, “he was deeply steeped in the blues and had an opportunity, early on, to play guitar with some great, blues legends like Yank Rachel, Sleepy John Estes and many others. He was one of the first of the great guitar heroes to appear in the sixties. Whether it was Butterfield, Electric Flag, or Dylan, his playing was impeccable and always right.

“After recording with Bloomfield and Naftalin, I visited both of them at their homes in the Mill Valley area, while I was performing in San Francisco. Mark Naftalin played accordion on my third album, Under My Own Disguise, a couple of years after the Ann-Margret sessions.”

Digital downloading music pioneer and guitar player David Kessel, a son of master guitarist and jazz icon, Barney Kessel, first discovered the Super Session LP in early summer 1968.

“Mike Bloomfield is one of the most outstanding guitarists of his generation,” Kessel proclaimed, who operates the cavehollywood.com website.

“The seemingly effortless flow of his fingers creating a majestic waterfall of blues interpretation is phenomenal. As a visionary from the Butterfield Blues Band to Dylan, he delivers big time. He helped pioneer new music trends for the blues, folk rock, and the guitar in general. His inspired playing on East West and ‘Don't Throw Your Love On Me So Strong’ is a gold standard of vision for blues and rock guitar.

“My brother Dan and I went to school in Switzerland, and while in Europe, our dad Barney pulled some strings to get us in The Bag O’ Nails club, in London to see Jimi Hendrix. Upon returning to Los Angeles in the early part of the summer of 1967, we went up to Sausalito outside San Francisco and stayed on a houseboat for 3 weeks. Our Dad was giging at El Matador (a Jazz club in San Francisco). Next to the houseboats, were a helicopter pad and some airplane hangers.

“We were lounging around one day when this bolt of guitar thunder came ringing out of one the hangers. Heavily intrigued and awed by the sound and playing, Dan and I sort of snuck up to the entrance and peeked in. By then the whole band was playing and nobody saw us quietly enter and go to a kind of hidden corner. We were absolutely blown away by the band, but particularly the guitar player who was playing stuff that we knew was extra special.

“It blew our mind when we recognized him as Michael Bloomfield, whom we already worshiped from the Butterfield Blues Band. He was playing a Les Paul guitar and was going through two Fender Twin Reverb amps. The echo in the hanger with the reverb was a gigantic guitar sound. After several songs, the band took a break, and at that point we were spotted. The singer, who we found out later was Nick Gravenites, got kind of mad and said ‘what the hell are you kids doing here?’

“Michael came over and told us it was a private rehearsal. We asked the name of the band, and were told by these guys they were Electric Flag, and that they were getting ready for their first gig, playing the Fillmore. Hoping that it might help our plight of wanting to stay and dig the music, we said to Michael ‘our dad is Barney Kessel, he’s a jazz guitarist, don’t know if your familiar with his work and we’re staying in one of the house boats right here. We heard you and it sounded so good, we had to come over and check it out.’

“His reply was ‘Barney Kessel is your dad! Well you guys you can hang out as much as you want, and in return do you think you could introduce me to him. I mean, that guy is unbelievable.’

“We said ‘sure Michael, we’ll bring him by tomorrow.’ Michael turned to the band and said ‘leave these guys alone, they can come and go as they please.’ There were a few groans from some of the guys. The next day we were able to talk our dad into meeting Michael and saying hello.

“As we were talking to Michael outside the rehearsal hanger, waiting for our dad to arrive, we asked him if he was hip to a guy named Jimi Hendrix (this is right around the time Jimi was to be introduced to the US through the Monterey International Pop Festival). We told him that Jimi was a way out guitar guy and that we had seen him in London and he was ripping things up, and we already had some of his UK records that we brought back home from Europe.

“We were surprised that nobody here in the states that we talked to, knew who he was. He looked at us and kind of turned a little sweaty and said ‘Oh yeah man, that cat is a little scary.’

“We asked Michael if he knew Jimi used Marshall amps (he did) and talked about the difference between his set up (Gibson Les Paul Guitar and Fender Twins amps) and Jimi’s set up (Fender Stratocaster & Marshall amp stacks).

“Right about then, we see our dad is on his way to meet Michael, and we could see a profound respect from Michael towards our dad as he approached. He started kind of fashioning his hair with his hands, stood up straight, and patted down his un-tucked blue work shirt. Michael stuck out his hand and said ‘Hello Mr. Kessel. I’m very pleased to meet you. I’m a guitar player who plays the blues. I want you to know that your kids have been welcome at our rehearsals, and have expressed an appreciation for my playing. I take that as a very high compliment, with you being their dad and all. I really wanted to be able to say that I met you, talked to you, and shook your hand.’

“They chatted about music for 10-15 minutes, and our dad excused himself, as he had to go into the city (San Francisco). Electric Flag rehearsed several more days before heading to the Fillmore, for the very first Electric Flag gig. What a unique, cool, and one of a kind experience.

“Coming out of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and Electric Flag, Michael Bloomfield was poised to lay down some of his powerfully fluent straight ahead Chicago Blues on tape, in a non- hassled atmosphere,” explained Kessel in our 2019 conversation.

“Nature abhors a void and Al Kooper filled it with Bloomfield on the Super Session recordings. Bloomfield is an extraordinarily great and special blues guitarist, who was really letting loose on the Super Session tracks.

“You can feel him just floating over the rhythm section with his amazing blend of his sharp, crisp, tone, and his celestial way of floating his fingers across the fret board in a seemingly effortless manner. This studio album provides Bloomfield an opportunity to really lay it on in a relaxed, but controlled environment, without the stress of pleasing or arguing with fellow band members.”

“I saw the Paul Butterfield Blues Band at The Trip,” Robert Marchese reminded me, the Grammy-winning record producer, Richard Pryor Live at The Troubadour, and manager (1970-1983) of Doug Weston’s Troubadour club in West Hollywood.

“The Butterfield band opened for the Byrds. I was walking on Sunset Boulevard and saw Michael and some of the band members in front of their motel the night before their opening night. ‘Hey! Are you the Paul Butterfield Blues Band?’ I had the first LP. They were in like in shock that somebody knew who they were. On the marquee of The Trip it displayed Byrds Byrds Byrds and in real small letters, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

“Bloomfield and I hit it off right away,” reiterated Marchese. “I liked Paul a lot, too. I talked primarily to Mikey. I said to Bloomfield, ‘I hate the Byrds. Tomorrow night blow them off the stage.’ After the first show, the Byrds really didn’t want to play after that. And the next night the marquee read Butterfield Blues Band. They had Elvin Bishop and the whole crew. Bloomfield on stage was tremendous. He just wailed.

“Coming from Chicago, Bloomfield and Butterfield went into those fuckin’ clubs to see Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters and were the only white kids who went in there and actually were asked to come up on the stage to play.

“Once Bloomfield got involved with Dylan in 1965 everybody wanted him. At the time, before Jimi Hendrix, Michael Bloomfield was the guy. You know what I mean? In a lot of ways everybody says Clapton, but I always thought Bloomfield was a lot more electric. At the time, you’d hear around town, like when they talked later about Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughn, ‘Mike Bloomfield is coming!’ That kind of stuff.

“And I think the worse thing Michael and the Butterfield band ever did was wind up in San Francisco with the Grateful Dead. The promoter Bill Graham liked the Butterfield group a lot and they played the Fillmore often.

“I was with Bloomfield in 67 at the Monterey International Pop Festival. The Michael Bloomfield Thing which was the Electric Flag was really good and they were dynamite. It was intense and Buddy Miles’ first thing. He was a very shy kid and became a star there. Michael was the cat. I just always thought Michael was better than Clapton. I liked everything Mike did and I wasn’t a big horn guy.

“Mike and I sat together with Michelle Phillips and watched Otis Redding. He had never seen him. Mike went crazy. ‘Jesus Christ!’ Michael was a happy-go-lucky space cadet. We saw Jimi Hendrix at Monterey. I was standing behind the amps on stage.

“The Electric Flag album that eventually came out was kind of weak in terms of material. But the playing was real good.

“I managed the Troubadour for over a decade. One night I’m at the club and the girl at the box office comes over to me and says, ‘Mike Bloomfield is on the telephone from San Francisco and wants to talk to you.’ It had been a year since we talked. ‘Hey, what’s up, man?’ ‘Robert. How you doin’? Did I get nominated for a Grammy?’ ‘Yes you did.’

“Mikey and I kept in touch over the decades. He was great but I just wanted to grab him one time and punch him in the mouth and say, ‘Get off of this shit! You don’t need it, you know.’

“I knew he was starting to get fucked up, which was sad, because he was a good dude.”

“Mike Bloomfield was an all-star guitarist,” offered Carol Schofield, owner of MsMusic Productions and High Desert Records in Yucca Valley, Ca.

“Mike’s guitar (s) sang... the long smooth notes wafted through the air… He had a lot of feeling when he played. His love for music was on display. Soul and heart.

“He is one of the great music icons and spirits of our music generation. He and Al Kooper on Super Session complemented each other completely. I went to their 1968 live recording at the Fillmore West. I still have the original poster. Mike was such a caring person that he taught music in Marin County. I had the opportunity to be at his funeral service at the Mt. Sinai Memorial Chapel on Divisadero Street in San Francisco.”

Mill Valley, Ca. resident Bloomfield battled insomnia for many years and medicated with heroin. A coroner’s report concluded he died at age 37 in San Francisco of cocaine and methamphetamine poisoning.

Michael Bernard Bloomfield’s tombstone is located in the Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery a Jewish resting place in Culver City, near L.A. Barry Goldberg delivered the eulogy.

“Mike Bloomfield was the original guitar hero even before Clapton at least in my hood,” suggested musicologist/drummer Paul Body.

“I don't how we knew about him but we did. Maybe it was ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ but mostly it was the guitar strangling on the first Butterfield album. He was a true character, just check out his bit in the movie Festival. Saw him at the Monterey International Pop Festival with Electric Flag right after he split from Butterfield, lots of horns and Buddy Miles and it was just as advertised American Music.

“Got to see him up close backstage at the Shrine Exposition Hall in downtown Los Angeles. He was jamming with Jimi Hendrix. I heard that before I got there that when Bloomfield showed up and Jimi started playing Bloomfield's licks that is how heavy he was. Anyway, in 1968, he could make that Les Paul do everything but crawl on its belly like a reptile.

“Unfortunately he was chased by demons, so by the time I saw him at The Troubadour he wasn't even playing his electric guitar anymore. The sting was gone. Too bad because he was one of the cats who got the blues revival going back in '60s. Mike Bloomfield was a bluesman.”

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 15 books, including titles on Leonard Cohen and Neil Young. His 2017 volume, the acclaimed 1967 A Complete Rock History of the Summer of Love was published by Sterling/Barnes and Noble. His Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection, Vol. 1 was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other Cottage Industries in March 2018.

The Doors: Summer's Gone has been nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections Awards for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research.

In November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s book, The Story of The Band From Pig Pink to The Last Waltz, written with his brother Kenneth Kubernik.

Harvey Kubernik’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown is in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett published in 2019 by Oxford University Press.

This century Kubernik penned liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century.

In November 2006, Kubernik was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.

During 2019, Kubernik is a screen interview subject for director Matt O’Casey for his BBC4-TV digital arts channel Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird. The cast includes Christine McVie, Stevie Nicks, Mick Fleetwood, Mike Campbell, Heart’s Nancy Wilson, and producer Richard Dashut.

In May 2014, filmmaker Matt O’Casey lensed Kubernik in his BBC-TV documentary on singer Meat Loaf, titled Meat Loaf; In and Out of Hell, broadcast in the US market in 2016 on the Showtime Cable TV channel.

Kubernik was a featured talking head in O’Casey’s 2012 Queen at 40 documentary broadcast on BBC Television and released as a DVD Queen: Days Of Our Lives in 2014 via Eagle Rock Entertainment.

In 2013 Harvey Kubernik was interviewed for the 2013 BBC-TV documentary on Bobby Womack Across 110th Street, directed by James Meycock. Womack, Ronnie Wood of the Rolling Stones, Damon Albarn of Blur and the Gorillaz as well as actor Antonio Vargas are featured. https://nwfilm.org › United Kingdom.

In the 2016 Neil Norman–directed documentary, The Seeds: Pushin’ Too Hard, Kubernik appeared in an on-screen feature interview, along with Bruce Johnston, Iggy Pop, Kim Fowley, the Bangles and Johnny Echols of Love. Movie sold out a June 2019 screening in London.

This decade Kubernik was filmed for the music documentary about the former Hollywood landmark Gold Star Recording Studio and co-owner/engineer Stan Ross, produced and directed by Jonathan Rosenberg and Brad Ross. Brian Wilson, Herb Alpert, Richie Furay, Mike Curb, Chris Montez, Nino Tempo, Bill Medley, Don Randi, Hal Blaine, Don Peake, Shel Talmy, Carol Kaye, Kim Fowley, Marky Ramone, Artie Butler, David Kessel and Steven Van Zandt were among those participating.

Kubernik is a former (1978-1979) West Coast Director of A&R for MCA Records, now Universal Music Enterprises, where he teamed engineer/producer Jimmy Iovine with Tom Petty. He also initiated the Petty-produced Del Shannon album, Drop Down and Get Me during his MCA tenure, eventually issued on Network Records and re-released over the last few decades.

Since 2008, Harvey Kubernik has written the monthly cover stories for Record Collector News magazine. The online version is also displayed at recordcollectornews.com as well his monthly contributions to cavehollywood.com.