Canadian poet, novelist, and teacher Margaret Atwood once said, “Human beings make art, that’s just what we do.” Atwood’s statement beautifully captures the natural inclination for self-expression, collaboration, and communication. But how well do you think the author’s statement would hold up in a world where art could be legally used by everyone at his or her own discretion for free? It wouldn’t. And that is exactly why there are copyright laws. Copyrights give artists just like you an incentive to create beyond just the pure pleasure of it.

But even when there are copyright laws and registration processes in place, there will be cases where people use your music without your permission, knowledge and payment (this is called infringement). Sometimes this is done out of ignorance, sometimes it is done by mistake, and sometimes it is done intentionally. Just be clear that registration does not stop stealing, it only makes it easier to sue people that do rip you off. That is why understanding the very basics about copyright infringement is extremely important. It can help you to feel more confident about the rights in your works, and it can help stop you from infringing others, too.

In any case, let’s take a quick look at the definition of infringement and end with a series of famous cases.

What Is Infringement?

Section 501 of the United States Copyright Act states that copyright infringement is when someone uses your original works without your permission, knowledge, or compensation.

Rapper Vanilla Ice ripped off David Bowie and Queen’s classic “Under Pressure” when he recorded and distributed his hit “Ice Ice Baby.” And Led Zeppelin ripped off Willie Dixon’s song “You Need Love” when the band recorded and distributed the classic “Whole Lotta Love.”

The examples of copyright infringement are quite plentiful, and they occur—not just by shady criminals lurking in the dark web—but by some of your favorite and beloved artists.

Any Substantial Damage?

When you discover that someone is infringing on your rights, you must first consider what the damage really is. Of course, in principle it’s wrong (how dare someone steal your art!) and it’s your right to stop them from doing it. But, for any attorney or judge to take an infringement case seriously, you need to have suffered a substantial loss.

Substantial Loss is Likely

If you hear your song played in a television commercial or in a movie, or see it released by a major label and streaming into the millions on Spotify, you’ve probably suffered a loss of income as a result. At this point it might be helpful to speak with an attorney to discuss your options.

Substantial Loss is Unlikely

If you hear that your former bandmates recorded one of the songs you co-wrote with them and sold 20 vinyl albums in the past year or received 50 streams on Spotify, there’s really very little damage other than your hurt feelings. You can hire an attorney for $150 to $300 (or more) to write a cease and desist letter (demanding your former band stop selling/streaming the song), but no one really gives a damn. Fight the battles that are really worth fighting.

What Do You Have to Prove?

Should you feel there’s substantial damage and an infringement exists, then it just might be time to go to battle. To illustrate the various elements commonly involved in proving an infringement case, let’s look at a real-life example between a local opening act and a major label band.

Case Study:

Local Unknown Versus Major-Label Giant

In the early 1990s, a small, unsigned band hired an attorney to sue a successful major-label recording artist for copyright infringement (sorry, the names must remain confidential here). In the suit, the band claimed that the artist’s hit song contained a chorus that was an exact replica (both melodically and lyrically) of one of their own. Here’s how it all went down.

Registration: The local band showed that they had registered the published song with the Copyright Office within three months of the first publication, which was long before the major-label act had registered it.

Access: The local band was able to prove the likelihood that the artist could have stolen its composition. This is called “proving access”—the local band had opened for the major label artist on several occasions and had newspaper clippings and testimonials from the promoter to back it up.

Substantially Similar: The local band was able to show that the major-label artist’s chorus was “substantially similar” to their own. A musicologist testified and matched the notes of the two songs side-by-side on a staff.

Unique in Character: The local band (and its music experts) were able to show that its chorus was so unique in character, it undoubtedly was copied intentionally. In other words, the infringement was “willful.”

Witnesses: The local band brought in a witness whose life the lyrics documented—a friend who had been in a serious car accident and almost died.

Proof of Publication: The local band exhibited newspaper clippings showing the recording for sale with mention of the song in question as the featured track.

Damage: The local band was able to show that they had suffered substantial financial loss as a result of the infringement, by showing Soundscan reports of sales attributed to the major-label artist and Billboard charts indicating the song’s charting position.

Needless to say, there was substantial evidence in the local band’s favor. The case was settled out of court, and the band received an undisclosed sum of money. Bam!

Sampling and Infringement

Moving into a more frequent area of copyright infringement, let’s talk briefly about “samples.”

Remember that samples are song snippets (either re-recorded or lifted from an existing sound recording) to enhance a musical track. A snippet that is re-recorded is typically called an “interpolation.”

While there is a lot of confusion in this area, just be clear that samples require permission from, and compensation to, the copyright holders of the music and/or the copyright holders of the sound recording (which may be two or more separate entities).

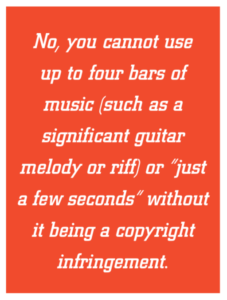

No, you cannot use up to four bars of music (such as a significant guitar melody or riff) or “just a few seconds” without it being a copyright infringement.

By not properly “clearing” a sample use before releasing a project, you are accepting the risk of having to either 1) clear the rights at a later date for a much higher fee/split, or 2) defend yourself in an infringement lawsuit. Plain and simple. So be careful!

Best Course of Prevention

With all of this talk about infringement and lawsuits, you may be wondering what’s the best course of protection against being infringed and against infringing others. Good question!

Against Being Infringed

The best course of protection is to do the following: work with reputable people, acknowledge in writing your contributions to co-authored songs, and register your songs prior to their publication (or within three months after the date of publication). That’s really all anyone can do!

Against Infringing Others

As for being careful not to infringe others’ rights, be mindful when sampling other people’s works—an area where infringement is most likely—and get proper clearances and permissions from the publishers (and/or master owners) prior to publication.

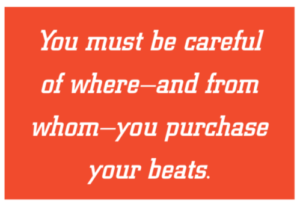

When buying beats, you should also make sure the beat does not include unauthorized samples—remember what happened to Lil Nas X and the song “Old Town Road?” Unbeknownst to the rapper, a beat he bought contained an uncleared sample from Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails. Reznor now owns a piece of the hit.

Further, should you create something original that sounds too familiar, know that it just might belong to someone else—ask your peers to identify the source before you run off and record and distribute it. Would you believe that George Harrison (yes, the almighty Beatle) was charged for “accidental infringement?” Yup, it’s true! So, next time you write something that sounds like a hit, know that it just might be a hit that already belongs to someone else.

More Case Studies

in Copyright Infringement

To wrap up this article and ensure that you really understand infringement, let’s take a look at a few more real-life/popular examples and briefly explain what happened. Note: Many infringement cases are often solved out of court, so the terms of the settlements are unknown.

Ronnie Mack (The Chiffons) Versus George Harrison

Ronnie Mack (whose song “He’s So Fine” was recorded by The Chiffons in 1962) sued George Harrison of the Beatles (who released “My Sweet Lord” in 1972).

Mack claimed that Harrison’s verses were substantially similar to his own verses and that Harrison had access to infringing the song given the hit success of the song by The Chiffons in 1962.

While Harrison claimed that he did not have to rip anyone off because he was a Beatle capable of writing his own hits, and that he was actually inspired by a public domain hymn “Oh Happy Day,” Harrison was nonetheless found guilty of accidental infringement and required to pay approximately $500,000, which was a lot of money back then.

Tom Petty Versus Sam Smith

Tom Petty (who wrote “I Won’t Back Down” in 1989) made a claim against singer Sam Smith (who released “Stay With Me” in 2014).

Petty felt that Smith’s verses and chorus to “Stay With Me” were substantially similar to his own song, not to mention, that Smith had access to infringing Petty’s song given its success.

Smith did not disagree. In an out-of-court settlement, Smith gave both Tom Petty and his co-writer Jeff Lynne (of ELO fame) a 12.5% share each of “Stay With Me.” Sam stated that the similarity was a “complete coincidence” and he did not hesitate to credit “I Won’t Back Down.” This is yet another example of how you can accidentally infringe someone’s song, so be careful!

Spirit Versus Led Zeppelin

A representative for the band Spirit (a group who wrote the instrumental “Taurus” in 1967) sued Led Zeppelin (who released the classic song “Stairway To Heaven” in 1971).

Spirit’s representative claimed that the opening riff to “Stairway To Heaven was significantly similar to the main riff of “Taurus.”

While the riffs do sound identical in our opinion, Led Zeppelin’s was not found guilty by a jury in 2016 on what many believe was a technicality. You see, because the sheet music was the only deposit copy submitted for registration back in 1967 (since sounds recordings were not protected by federal law back then), the judge did not allow the jury to hear the actual sound recording of the song during the trial.

Feeling that the judge had given incorrect jury instructions, Spirit’s representative appealed and a new trial with a series of new judges was eventually ordered in 2018. Nevertheless, the result was the same. It was determined that the original judge had in fact given correct jury instructions and so Led Zeppelin remained victorious.

Spirit’s representative tried as a last ditch effort to take the case to the Supreme Court to be reviewed and potentially sent back to the courts but on Oct. 5, 2020 the highest court in the land decided they were not going to hear the case. So this long saga is over and Led Zeppelin’s claim and legacy surrounding their signature song remains intact.

Marvin Gaye Versus Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams

The Marvin Gaye Estate (owners of “Got to Give It Up” written by Motown legend Marvin Gaye in 1977), sued Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams (who released the song “Blurred Lines” in 2013).

The Gaye Estate claimed that “Blurred Lines” was similar in style and feel to the song “Got to Give It Up” and that—given the song’s massive success—Thicke and Williams had access to infringing it.

Thicke and Williams admitted that they were inspired by Gaye and the Motown sound, and that the song was similar in tempo and used similarly percussion and background sounds of people, but they argued that “influence” alone is not the same as copyright infringement. Thicke and Williams argued that there were no similarities in the melodies and lyrics and that there were no samples used from the song “Got to Give It Up”.

Nevertheless, in a judgment that shocked the music community, a jury still found in favor of The Marvin Gaye Estate.

Thicke and Williams appealed the decision, not only because it set a terrible precedent for future creators who would feel fearful of being sued over “influence,” but because they felt that the judge wrongly admitted certain evidence into the trial. You see, despite the fact that the sheet music was the only deposit copy submitted for registration by Gaye (since sound recordings were not protected by federal law at the time), the judge still allowed the jury to hear the actual sound recording of the song.

All things being said, in the end The Marvin Gaye Estate still won the appeal and is now entitled to half of all the royalties to the song “Blurred Lines” moving forward. Wow.

The Rolling Stones Versus The Verve

A representative for The Rolling Stones (a band who wrote the song “The Last Time” in 1965) put the squeeze on the band The Verve (who released “Bitter Sweet Symphony” in 1997).

The Stones’ rep (Allen Klein, who was the Stone’s publisher and manager at the time) claimed that while The Verve’s record label did properly obtain a sample license for an orchestral part lifted from the Stones’ master recording of “The Last Time,” The Verve did not clear the musical composition (yes, a sample can consist of both the master and song, or just an interpolation of the song).

Being that sample licenses are completely negotiable (the authors/owners can ask for whatever they want), Klein decided that he would demand the maximum—he now wanted to publish 100% of “Bitter Sweet Symphony” through his publishing company ABKCO and to list Mick Jagger and Keith Richards as the writers of “Bitter Sweet Symphony.” The Verve, who felt they had no legal rights in the matter, received absolutely nothing. That totally sucked!

But in 2019, ABKCO worked out a deal to return the songwriting credits to The Verve’s Richard Ashcroft so that he could finally benefit from the work he did on the song. ABKCO, however, still remains 100% publisher of the song.

Wow! So remember this kiddies, be sure to clear “all” sample rights (master and/or song) before you release your next big hit, or you could end up in a bitter sweet symphony.

Huey Lewis and the News Versus Ray Parker, Jr.

Huey Lewis (who wrote “I Want a New Drug,” in 1984) sued Ray Parker, Jr. (who released “Ghostbusters” in 1984—note this song was also the theme to the popular movie Ghostbusters).

Lewis claimed that Parker’s “Ghostbusters” was substantially similar to “I Want a New Drug” and that Parker had access to stealing the song given the hit success of Lewis’ song in 1984. Furthermore, Lewis believed that Parker willfully infringed his song, given that it was Lewis who was initially asked to create the Ghostbuster theme—according to Lewis, the producers of the Ghostbusters film must have asked Parker to create something similar to the Huey Lewis sound.

While the two parties settled out of court in Lewis’ favor for an undisclosed sum, Lewis was later sued by Parker when he broke a confidentiality agreement made between the two parties. Apparently Lewis discussed the case in a television interview, letting his ego get the best of him! Sometimes, ladies and gents, you just have to know when to shut your mouth!

Flame Versus Katy Perry

Christian rapper Flame (who wrote the song “Joyful Noise” in 2008) sued Katy Perry (who released the song “Dark Horse” in 2013).

Flame claimed that a repeating eight-note phrase or beat in Perry’s “Dark Horse” was similar to one found in “Joyful Noise.” Further, he claimed that Perry had access to stealing the phrase/beat given that “Joyful Noise” was widely distributed (with millions of YouTube and Spotify plays) and also noted that Perry got her start in the Christian music scene.

Perry fired back stating that the part (which is essentially two notes repeating four times each) was not significant or original enough, and thus was un-protectable under copyright law. She further argued that considering this as an infringement would seriously hamper the creativity of artists for years to come because it would be like taking away the musical alphabet. Finally, she claimed that she had never heard of Flame or his song “Joyful Noise” till the lawsuit.

In 2019 a jury awarded Flame with $2.8 million in damages. The verdict, however, was overturned after Perry appealed. In the new ruling, the judge found that none of the individual elements that comprised the repeating phrase in “Joyful Noise” were “independently protectable.”

At the time of this writing, Flame did not appeal, but the judge did note that she would conditionally grant a new trial if he did. Be sure to look for updates on this case.

Joe Satriani Versus Coldplay

Legendary guitarist Joe Satriani (who wrote the song “If I Could Fly” in 2004) filed a lawsuit against Coldplay (who released the hit “Viva La Vida” in 2008).

Satriani felt that the verse melody of “Viva La Vida” was substantially similar to an instrumental melody found in “If I Could Fly.”

Things got ugly in a war of words between them, but in the end, they settled out of court for an undisclosed sum in 2009.

One possible reason for the settlement is that Yusuf Islam (previously known as Cat Stevens) was considering filing his own infringement lawsuit against Coldplay claiming that his 1973 work “Foreigner Suite” bore a distinct resemblance to “Viva La Vida.” When asked whether he was considering a lawsuit, Yusuf was quoted as saying “it depends on how well Satriani does.”

Let’s see how long Satriani can keep his mouth shut (take note Huey Lewis).

Trent Reznor (of Nine Inch Nails) Versus Lil Nas X

Trent Reznor (who wrote the song “34 Ghosts IV” in 2008) found himself dealing with an issue over a matter concerning Lil Nas X (who released the song “Old Town Road” in 2019).

Reznor discovered that “Old Town Road” contained a sample of a banjo from “34 Ghosts IV.” Lil Nas X didn’t dispute it, and in fact, it was X’s manager who alerted Reznor of the matter. Apparently, X purchased the beat from a Dutch producer who never cleared the sample rights.

Given that the song made the Billboard charts in 2019, Reznor could have totally held X over the barrel for this one, but he reportedly said, “Look, I’m fine with it. Let’s just work it out.”

As it stands, Reznor is now listed as both songwriter and producer on the song together with the Dutch producer YoungKio and Lil Nas X. The song ended up being a diamond certified single and topped the Billboard Hot 100 for a record breaking 19 consecutive weeks!

While this example did not turn ugly, this sets a strong example, ladies and gentlemen, of how you must be careful of where—and from whom—you purchase your beats. Be careful!

Willie Dixon Versus Led Zeppelin

Blues legend Willie Dixon (who wrote the song “Bring It on Home” released by Sonny Boy Williamson in 1966), sued rock legends Led Zeppelin (who released the song “Bring It On Home” in 1969—not kidding, same titles).

Dixon claimed that the intro and outro of Led Zeppelin’s “Bring it on Home” was substantially similar to his original “Bring it on Home.” Apparently Zeppelin didn’t disagree. In fact, Zeppelin didn’t disagree with yet another claim by Dixon that the song “Whole Lotta Love” infringed Dixon’s song “You Need Love.” WTF Zep!

Both cases were settled out of court. Dixon was given full songwriting credit for “Bring It On Home,” and for “Whole Lotta Love,” Dixon’s name appears alongside Led Zeppelin.

David Bowie and Queen Versus Vanilla Ice

And finally, and perhaps the most infamous case, is one against rapper Vanilla Ice.

Queen and David Bowie (who jointly wrote “Under Pressure” in 1981) sued Vanilla Ice (who released “Ice Ice Baby” in 1989).

Queen and David Bowie claimed that the two-bar repeating bass line to “Under Pressure” was indeed a sample from their song and that Ice had access to stealing the part given the hit success of “Under Pressure” in 1981.

While Ice claimed rather jokingly that his song was different all because of one eighth- note he added to the end of beat four in the first measure, Ice settled out of courts for an undisclosed sum of money. Furthermore, Bowie and members of Queen all received songwriting credits on the track.

So, in closing, ladies and gents, please make every effort to respect other artists’ copyrights, and hopefully other people will respect your rights too. Copyright gives people an incentive to create, and without incentive, it especially makes it hard for new artists to thrive.

BOBBY BORG is a professor of music industry studies and an author of several music industry books including Music Marketing For the DIY Musician and Business Basics for Musicians on sale at finer book sellers. Borg can be contacted at bobbyborg.com.

BOBBY BORG is a professor of music industry studies and an author of several music industry books including Music Marketing For the DIY Musician and Business Basics for Musicians on sale at finer book sellers. Borg can be contacted at bobbyborg.com.

MICHAEL EAMES is the owner of PEN Music Group, a music publishing company, and he is also the co-author (with Borg and 3 other co-authors) of Five Star Music Makeover. Eames can be reached at penmusic.com.] Borg and Eames are writing a new book titled Intro to Music Publishing for independent artists, coming next year.