“I often read about artists that have supposedly shaped Americana music—Chris Darrow WAS Americana music. He always will be.” - Michael Macdonald.

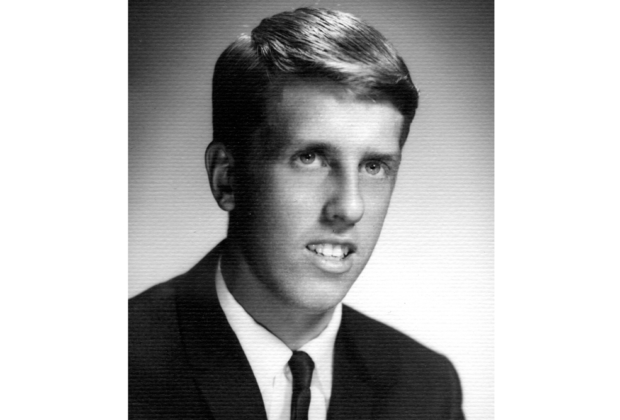

Influential musician and songwriter Christopher Lloyd Darrow was born July 30, 1944, in Sioux Falls, SD. He died on January 15, 2020, at 1:00 pm at the Pomona Valley Hospital in Pomona, CA following complications from a stroke.

I have interviewed Chris Darrow many times over the last 44 years.

I first saw Chris and photographer Henry Diltz in 1967 at a Love-In in Los Angeles at Elysian Park. Diltz eventually took the cover photo of Sweet Baby James.

The heralded multi-instrumentalist moved with his parents as a tyke to Claremont, CA (via Pasadena, CA). After high school at the Webb School and Claremont High, he attended Claremont Men’s College and graduated with a degree in Art and was in the MFA program at the Claremont Graduate School. Darrow has been in the same home since the '50s.

At Pitzer College in Claremont, Darrow was an assistant to the well-respected folklorist Guy Carawan, who gave the world the anthem “We Shall Overcome,” and it was Carawan who played opening night at the Ash Grove folk club in 1958. Carawan was teaching American Folk Life Studies at Pitzer College. For two years, Darrow worked for him at the school. Later, in the mid-'70s, Darrow produced an album on Carawan, The Telling Takes Me Home.

Darrow was co-founder of The Kaleidoscope and session man on Songs Of Leonard Cohen debut LP. Darrow is the bassist on “So Long Marianne” and “Teachers” from those 1968 recording dates.

Additional credits include work with John Stewart, Hoyt Axton and he served as Linda Ronstadt's band leader from 1969-1971. In addition, he worked onJames Taylor’s Sweet Baby James and was a onetime member of The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. Darrow also penned Ben Harper’s debut Virgin Records single “Whipping Boy.”

In late spring 2008, his first two solo albums were reissued on the potent Ever Loving Records label based in Los Feliz, CA.

The Kaleidoscope is considered a very potent and seminal band of the '60s. With David Lindley, Solomon Feldhouse and Max Buda, their blend of Middle Eastern, country, folk, blues and psychedelic music anticipated the world beat movement by decades.

In a '70s issue of the UK periodical Zig-Zag, Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page called Kaleidoscope “his favorite band of all time. My ideal band—absolutely brilliant. I saw them one time [in San Francisco] and they played all the numbers off Beacon From Mars, all that Moroccan stuff and having a whale of a time they were. They had such good roots and such a grip on their music.”

In a later edition of MOJO, Robert Plant, the fan, picked his 10 favorite musical trips, including the song “Taxim” from Kaleidoscope’s A Beacon from Mars LP. “I heard it in the Band of Joy (his pre-Led Zeppelin group). This indicated the lean towards fusing Middle Eastern music and underground rock.”

One of Chris’ compositions from the Kaleidoscope, “Keep Your Mind Open,” is now on the official list of top psychedelic songs at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Ohio. MOJO Magazine also rated the same Darrow tune, an anti-war composition, in their own psychedelic issue, but had the Pasadena/Claremont-based band as being from Berkeley, CA, a 450-mile geographical error.

One other loud endorsement about The Kaleidoscope on record can be found in the book, Follow the Music, the autobiography from Elektra Records founder Jac Holzman, who claims “Barry Friedman had produced one of my all-time favorite albums, the first Kaleidoscope for Epic.”

“In 1966 I got a chance to record on an album for the first time,” reminisced Darrow. “The Kaleidoscope was recording our first album, Side Trips, on the first eight-track recording machines in America, and in the same studio that Benny Goodman and many of the greats had recorded before. It was all very new to me and I would sometimes arrive early to hang out at the CBS Studios on Sunset Blvd., and just roam around. The Moby Grape recorded in the next studio over, sometimes the Byrds, and Donovan, who I met later, worked there as well. The studio served our label, EPIC, of course, Columbia and also Okeh Records, the R and B label headed by the great, Larry Williams.

"One day on my searching I ran into an interesting black man in the hallway. He had the look of the “cool” jazz musician of the day. A dark, 4-button suit, slim cut but ivy league, horned-rim glasses and the black equivalent of a crew cut. He could have been a member of the Modern Jazz Quartet, with Milt Jackson, John Lewis and Percy Heath, the way he looked. He was friendly, but also dead serious, and carried a slim briefcase. The man said he was a jazz DJ from San Francisco who was obviously also a musician. We walked into one of the unoccupied recording studios in the building; he sat down at the grand piano, pulled out some lead sheets and started to play. It was then that I took my leave. His name was Sylvester Stewart, 'Sly Stone.'

"By 1969 Sly and the Family Stone had become a huge act and I was into recording with my new band the Corvettes and rehearsing at the house of our producer, Mike Nesmith. Michael was obviously very successful after the Monkees and he had just made a production deal with Dot Records. The house had a number of rooms, a studio, an indoor/outdoor pool, 13 cars in the large drive, a trained guard dog and an electric gate. The house was on the top of the hill off of Mullholand Drive and had a great view. There was always cold Dos XX in the refrigerator by the pool. One day Nesmith announced that the house had once belonged to Sly Stone. Full Circle! 'If You Want Me to Stay' is my favorite Sly Stone song.”

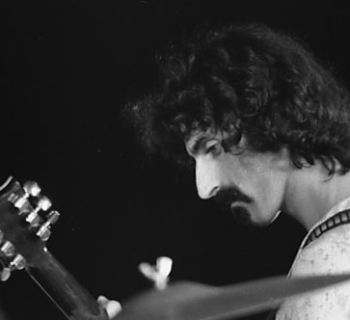

The Kaleidoscope played Steve Paul’s The Scene club in New York during December 1967 and Darrow has some unique accounts of this gig and encounters with Frank Zappa.

“I had just quit the Kaleidoscope due to musical differences and had nothing planned as my next move. Then I was asked by the band to join them on a tour to New York City. My replacement, Stuart Brottman, wasn’t yet able to join the band since he still had some dates to finish up with Geoff and Maria Muldaur.

“I had never been to New York before, so I accepted the offer and insisted on flying as opposed to driving with the band in 2 VW Vans. We were to be staying at the infamous Albert Hotel in the Village and upon arriving to unload our equipment, the vans were left unattended and a number of our instruments were stolen from the vans, including my classic Fender Telecaster. Thankfully, I had brought my rare, Premier Bass on the plane with me and, from that point on, it never left my sight. As it turned out before I arrived, the band had been turned down at the Chelsea Hotel, even after having reservations, for being too scruffy and dirty by the establishment. I believe the term “dirty hippie” was used more than once in their ouster.

“The first night at the Albert was a nightmare, as we all slept in a communal room and Solomon liked to play the clarinet all night long. Chester and I always got on well and he and I were the closest at that time. Later, I ended up moving in with a friend from high school, Charles Zetterberg, who was going to Columbia Law School.

“My first day out on the streets of New York was very eventful, however. It was the beginning of December and it was very cold and brisk outside. I had just walked out to the street, when I looked across the intersection and saw a guy in a full-length fur coat and long hair coming my way. He was waving at me and said, “Hey Chris, what are you doing here?” It was Frank Zappa, and he was on his way to his rehearsal hall down the street. I invited Frank to our gig and he invited me down the street to the Mothers Of Invention’s rehearsal hall.

“I had certainly arrived in New York!

“Opening night was very crowded and Zappa and members of the Mothers of Invention showed up to show their support. There were very few west coast groups that had played in the east yet, and we “long-haired hippies” were the antithesis of the New York vibe at the time. Warhol and his minions showed up, The Cyrcle was there, the Chambers Bros., Jim Fielder, Leonard Cohen and David Clayton-Thomas, pre-Blood Sweat and Tears were all hanging out.

“Our first set went fine and then it was time for Nico. I had met her in LA at Barry Friedman’s (aka Frazier Mohawk) house, so I knew a little about her. I was never really a Velvet Underground fan or into the Warhol scene. In fact I just thought that most of it was bad, New York posing. Nico’s delivery of her material was very flat, deadpan and expressionless and she played as though all of her songs were dirges. The German-born singer seemed as though she was trying to resurrect the ennui and decadence of Weimar, pre-Hitler Germany. Her icy, Nordic image also added to the detachment of her delivery. She was certainly beautiful, as Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich certainly come to mind. The audience was on her side, as she was in her element and the Warhol contingent was very prominent that night. However, what happened next was what sticks in my mind the most from that night.

“In between sets, Frank Zappa got up from his seat and walked up on the stage and sat behind the keyboard of Nico’s B-3 organ. He was so appalled at Nico’s caterwauling that he got up after her set and went up on stage and got behind her Hammond organ. He proceeded to start pounding on the keys and screaming. That was his interpretation of Nico.

“Frank placed his hands indiscriminately on the keyboard in a total, atonal fashion and screamed at the top of his lungs, doing a caricature of Nico’s set, the one he had just seen. The words to his impromptu song were the names of vegetables like broccoli, cabbage, asparagus etc. This ‘song’ kept going for about a minute or so and then suddenly stopped. It later became ‘Call Any Vegetable’ off the Absolutely Free LP. He walked off the stage and the show moved on. It was one of the greatest pieces of rock & roll theater that I have ever seen!

“The New York scene and the west coast attitude were very different at that time. The hippie deal was counter to the atmosphere prevailing in most of the east at that time. Frank was a breath of fresh air in our cold, metropolitan environs. A few days into the gig, a junkie looking for a score stole a bunch of our equipment from the club, and Frank loaned us some of his amps and drum stuff so we could finish off the week stint at The Scene. During this time we learned one of our engagements had been canceled at The Café Au Go Go, so we booked a show at Fun City, a mob joint on 42nd Street. The dressing room had an autographed photo of Frankie Lyman on the wall, and the Go-Go dancers would start in the Fun City window around noon. Frank saved us!”

One of the most rewarding conversations with Chris was learning that in 1967, Chris and fellow band members in the Kaleidoscope, Chester aka Max Buda and David Lindley, were asked by Cohen to play and support him in his John Hammond, John Simon and Bob Johnston produced debut LP, Songs of Leonard Cohen.

The initial vinyl pressings of the album didn’t list the musicians in the credits. Decades later they were corrected in the first compact disc configuration package text.

Darrow is the bassist on “So Long Marianne” and “Teachers” from those 1967 recordings.

Other original masters culled from the Bob Johnston-produced Cohen/Kaleidoscope sessions “Sisters of Mercy,” “Winter Lady” and “The Stranger Song,” were later utilized in director Robert Altman’s film McCabe and Mrs. Miller.

Three authors who penned books on Leonard Cohen this century contacted me to source my findings and subsequently interview Darrow about his once-hidden Cohen studio history.

“Opening night at The Scene was very crowded and Zappa and members of the Mothers of Invention showed up to show their support. There were very few west coast groups that had played in the east yet, and we ‘long-haired hippies’ were the antithesis of the New York vibe at the time. Warhol and his minions showed up, The Cyrcle was there, the Chambers Brothers, Jim Fielder, Leonard Cohen and David Clayton-Thomas, pre-Blood Sweat and Tears were all hanging out.

“The house band at the Scene was led by Rick Derringer and they had a jam session every Thursday night. That’s where I hung out with David Clayton- Thomas and was thrilled to see one of my favorite guys, Sir Monti Rock III, who later became Disco Tex and the Sex-O-lettes, do a few songs.

“During the week I had a chance to get close to Tiny Tim, who I liked very much, and on opening night, Leonard Cohen came up to me in the bar light. He was the palest guy I had ever seen and was wearing a black leather suit coat and carrying a black leather briefcase. He loved our band and was wondering if we would be interested in playing on his forthcoming album. I didn’t know who he was at the time and told him to talk with our managers who were at the bar. The next day, we were in his apartment, trying to play some of his songs. He was having trouble finding musicians that could play his stuff. Since he wasn’t a great guitar player, it was hard for some people to figure his music out. David, Chester and I played on some tracks that became Leonard Cohen’s first album, The Songs of Leonard Cohen.”

In 2001, poet and songwriter Leonard Cohen looked up from a local Claremont, CA Greek restaurant, Yianni’s, and saw a familiar face from 34 years ago. Chris Darrow.

At the time Leonard was on a break from his nearby Buddhist retreat Mt. Baldy Zen Center in Darrow’s neighborhood.

“Boy, you guys really saved me when I did my first album in New York,” happily confessed Cohen. “Chris,” asked Leonard, “what have you been doing?”

“As a member of the Kaleidoscope, I encountered Jim Morrison and the Doors a number of times. We did gigs together but the most memorable of the meetings was in 1966 in New York City. I was being courted by the Dirt Band to join up and I went to see them play at Hunter College co-billed with the Doors.

“While backstage, I saw Jim and he called me into his dressing room. He had a rather detached look on his face and flatly asked me, ‘Have you ever tried ether?’ I said, ‘No’, and removed myself from the room. Last decade I was invited over to Ray Manzarek’s house for a visit. He’s a great guy and a fabulous player.”

With the Kaleidoscope, Darrow recorded with R&B giants Larry Williams and Johnny “Guitar” Watson.

“After two years in the Kaleidoscope I decided to leave the band for reasons of direction. While on my last tour with the band I was in New York City playing at a club called The Scene. I was not sure what was next for me, and, since I was a husband and father, the possibilities of going back to school or finding a job seemed insurmountable at the time.

“The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band was in town and heard that I was leaving the Kaleidoscope. The Dirt Band was losing one of their core members, Bruce Kunkel, and was looking for a replacement. Jeff Hanna and John McKuen approached me about joining the band. I said to them that I wanted to attend a performance and then I would make up my mind. They had a concert at Hunter College on a co-bill with the Doors. I had had some contact with Morrison in LA, so I felt good about seeing some guys from home and the possibility of work was encouraging for me too. Jim Morrison and I had a brief exchange before the show and then I saw the concert. The Dirt Band was great and I said ‘sure’ to their invitation to join and said I’d stick around for at least a year.

“The Dirt Band was like a family and was managed by Bill McKuen, John’s brother. In addition, he managed other artists, Steve Martin, The Sunshine Company and The Hour Glass, a band from Georgia who later became the Allman Brothers. We all hung out a lot and, over a period of time, I became friends with most of the people in the bands, especially Duane Allman. He and Ralph and Holly Barr were very tight and when I was in LA (I lived in Claremont), I spent a lot of time at their house and got to know Duane. Both he and Ralph were phenomenal guitar players and there was mutual respect all around.

“One night on December 10th of 1967 the Dirt Band had a radio interview at a club called the Magic Mushroom in Studio City hosted by Phil Procter and Peter Bergman of the Firesign Theater for their Radio Free Oz program on KRLA. I had a blue, 1954 Ford two-door and had some room in the car for some riders. Jeff Hanna was in my front seat and Duane wanted to come along for the ride. We all had heard earlier in the day that Otis Redding had been killed in a plane crash somewhere in the south. I will never forget Duane sobbing in the back seat of my car over the death of his ‘main man.’ I remember back to the time when I cried uncontrollably when I found out about the death of Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens. When our heroes go what else is there to do?

“Duane and I kept in touch over time and after I had left the band I began to tour with Linda Ronstadt, John Stewart and Hoyt Axton. While in Linda’s band I usually roomed with Bernie Leadon. While spending a season in the New York area we were staying at the Chelsea Hotel on 22nd street. One day I got an exited call on the phone. It was Duane Allman and he had just gotten his first National resonator guitar and he had to show it to us. He had gotten it at Manny’s, as I recall, and he was bursting with enthusiasm. Both Bernie and I were dobro players and we all ended up sitting around with him taking turns and talking about tunings and technique. Duane was a natural slide player and learned to play real fast.”

As a solo act he opened for a series of shows in the early ‘70s for Muddy Waters.

“One of the great benefits of being in the music business is a chance encounter one with your heroes,” exclaimed Darrow. “I had the honor of opening for Muddy Waters at Ebbets Field in Denver, Colorado while supporting my second solo album, Chris Darrow, with Frank Reckard as my lone accompanist. Since I play a number of instruments, it’s always important to have a great player supporting you. Frank, who took my place in Hoyt Axon’s band and played with Emmylou Harris for 13 years, is my favorite guitar player.

“Both of us had cut our teeth on Muddy’s music and were thrilled to share a dressing room with him and his band. He fronted a 6-piece group featuring Hollywood Fats on guitar. I was playing guitar, fiddle, mandolin and slide guitar, which I played standing up on a six-string Fender lap steel with three legs. My primary slide song was Whipping Boy from the latest record. Muddy, being one of the great slide players, went out of his way to compliment both Frank and I on our playing.

“It was the Saturday night of our gig and Muddy and his best friend/road manager were playing cards and drinking pink Champale. Frank and I were preparing to go on stage for our first set when a black guy, dressed like a pimp, showed up with his entourage and burst into the room. He seemed to know Muddy and was very animated to the point that he started talking about how come he (Muddy) had to share a dressing room with ‘these white boys.’

“Muddy put down his cards, looked up at the guy and asked them to leave in no uncertain terms. ‘These are my friends,’ he added as he told them to leave the room.

“Frank and I were so impressed by that gesture that it still rates as one of the great moments of our lives. It was like shaking hands with the Dalai Lama, which I got to do a few years down the line.

“Later that night B.B. King showed up to say hi and sit in with Muddy. Ebbets Field was a small club, so being able to meet and play with two of my major heroes up close was a once in a lifetime experience. B.B. even came up to Frank after our set to compliment him on his mandolin playing. The two were so conciliatory and showed so much affection towards each other. It was beautiful to see these two kings of the blues say back and forth, ‘You’re the king, no you’re the king.’”

This past 2019, music journalists, record reviewers, writers, online bloggers, influencers, radio programmers and deejays started touting and praising the 50th anniversary of James Taylor’s landmark Sweet Baby James album that is housed with five other Taylor titles as both 6-CD and 180-gram, 6-LP sets, as well as digitally. The Warner Bros. Albums: 1970-1976.

Potential chroniclers and targeted consumers for this Taylor package that implements Sweet Baby James, nominated for two Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year, should know additional information and regional facts pertaining to this landmark SBJ disc, the nascent Southern California folk and country-rock genre, and Linda Ronstadt’s 1969-1974 touring and album repertoire multi-instrumentalist Chris Darrow unselfishly helped establish and develop.

I recently glanced at James Taylor: Long Ago and Far Away, the first definitive biography of the singer-songwriter by Timothy White published in 2001. A writer and critically acclaimed author, White was editor-in-chief of Billboard magazine from 1991 until 2002.

I was miffed that noted songwriter, the late great Chris Darrow, a co-founder in 1966 of the influential eclectic psychedelic worldbeat band Kaleidoscope and a contributing force in creating the 1968-1972 SoCal folk and country-rock/soft rock sound in Sweet Baby James was only mentioned as “a nifty fiddle player.”

Darrow’s numerous pre-production connections and functions in service for Taylor’s Sweet Baby James were totally ignored and White’s description of Chris totally diminished his participation in the planning and creation of it.

He didn’t even list Chris Darrow’s name in the index.

White was a music journalist whose research and scholarly writing I enjoyed and respected, but failed in reporting and citing Darrow’s fingerprints on the epic Taylor long-player.

At least author Mark Ribowsky in his 2016 book Sweet Dreams and Flying Machines: The Life and Music of James Taylor devoted a paragraph to Darrow’s role in Sweet Baby James.

With the Sweet Baby James 50-year milestone celebration, I thought it was timely to ask team player and Inland Empire-based A&R man Chris Darrow the backstory behind the glory of Sweet Baby James.

Darrow recommended the recording studio in Hollywood, Sunset Sound, and engineer Bill Lazerus. Chris had recorded at Sunset Sound earlier in 1969.

Fiddler Darrow also enlisted bassist Randy Meisner, a future Eagle, an old friend from the band the Poor, who were on Epic Records at the same time as Kaleidoscope, they shared the same producer, Barry Friedman, aka Frazer Mohawk, bass player John London, who he was with the Corvettes in, as well as drummer Russ Kunkel into the project.

Darrow also telephoned Red Rhodes, the respected pedal steel guitar player who was added.

“The opening act when I saw Cream at the Whisky A-Go-Go, Things to Come, was a local group from Long Beach,” recalled Chris. “Their drummer, Russ Kunkel, was married to Cass Elliot’s sister, Leah. He and the bass player, Bryan Garofalo, were in John Stewart’s band when I joined his group in the late '60s.”

It was Russ Kunkel’s first album session and in Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band drummer’s Max Weinberg’s book, The Big Beat, Kunkel cites Darrow’s effort in jumpstarting his career.

I discussed this circumstance with Russ in 2010 when I worked as the Consulting Producer on director Morgan Neville’s Troubadours: The Rise of the Singer-Songwriters which showcased the careers of Carole King and James Taylor. Kunkel went out of his way to insist I said a warm hello to Chris and to thank him again for that first paid session job.

Perhaps Australian-based writer and music historian Michael Macdonald captured Darrow best when he stated in a 2019 email to me, “Chris Darrow will never run with the pack simply because he’s always so far ahead of it. A genuine eclectic with a working knowledge of music that is encyclopedic, his only rival would have been Doug Sahm.

“Country, Cajun, world beat, bluegrass, folk, rockabilly, blues, Hawaiian rhythms, surf and flat-out rock ‘n’ roll are some of the many musical forms Darrow has explored in his 40-year plus career. Can also add that Chris Darrow was Alt-country and Americana long before those terms were minted.”

Michael Macdonald for years has been in a correspondence with musician Mabron McKinney, original bassist with the Hourglass, later recorded with Hearts and Flowers and played bass on the debut Linda Ronstadt album.

In a 2019 email, Macdonald presented a seminal moment in rock & roll history that Chris Darrow arranged which still pays dividends for many people.

“As you'll read, Mabron knows the deal—but I never knew Mabron was part of Hearts and Flowers. As he runs it down, the Hearts and Flowers connection got him an in with Linda Ronstadt's deal.

“The way Mabron tells it, Darrow hooked up Glenn Frey and Don Henley with Bernie Leadon. Easy to work out what came next—translates that Chris was THE man who helped draft the Eagles—Mark 1!

“After I left the Hour Glass, I played with a folk-rock group called Hearts and Flowers for a short period of time before it was time for me to leave and come back to Alabama and start my long and diverse college education... anyway, I was there the day Bernie Leadon pulled up in his old VW Bus direct from Daytona to take Rick Cunha's place on guitar.

“We didn't even have a drummer, it was just Larry Murray lead singer and acoustic guitar, David Dawson back-up vocal and auto-harp, and me on bass and back-up vocals; even though I am not mentioned on their web site, but that ain't the first time I've gotten short-changed and screwed in the many reviews written about bands I've played with...!

“Anyway I was asked to play bass on the first Linda Ronstadt album (that Nik Venet produced) as their scheduled bass player couldn't make it that night. Larry set it up and late the next evening Larry, Bernie and myself went down to the famous, round, 12-story Capitol building (that looked like a stack of albums).

“We went in through the sloping basement entrance, then on into one of the studios for the session which I'm sure Chris was a part of. It was there that Chris met Bernie and it was through Chris that Bernie was introduced to Glenn Frey and Don Henley. In fact, when I left to start college, Bernie also left and teamed up with Glenn and Don to form the Eagles...!”

“Mabron ran it down beautifully,” expressed Macdonald.

“CD pointed Bernie Leadon to Henley & Frey and we all know what came out of that hook-up,” Michael reinforced. “Having Bernie in the Eagles gave Henley & Frey the instrumental cachet they both needed.

“Same deal with the Sweet Baby James - CD very much assembled the studio band for Taylor and, in many ways, it's why the album still holds up. The blueprint for the Southern California country-rock singer/songwriters,” summarized Michael.

“Here in Oz back in the day, nearly every girl in my high school class went out and grabbed a copy of Sweet Baby James - my teenage crush Lee McDonald alternated between SBJ and Carole King's Tapestry and she later marveled: ‘Just love the spare sound on both records because it doesn't trample over the singer and lets the songs breathe.’

“Chris Darrow was really the architect behind Sweet Baby James' warm sound where acoustic guitars worked in and around pedal steels, Cajun fiddles and a subtle rhythm section. Had Chris not recommended several players, the studio and engineer, the album could have been a sonic wipe-out. Says it all really.

“One of Chris’ many positives is his total lack of elitism. It’s this trait that Darrow can understand why a true primitive like Jimmy Reed can share the table with sophisticates like Duke Ellington. It’s only Darrow who can groove to Bing Crosby and Nat Cole while being fully hip to why Nirvana and Oasis came to be. Chris Darrow-a man whose personal six degrees of separation are linked to Pat Boone, Helen Reddy, Leonard Cohen, Gene Vincent, Larry Williams, and Johnny Guitar Watson.

“Darrow will neither burn out nor rust. Tomorrow he could write the Dixie Chicks next chart hit and the following week immerse himself in a project working with the most exotic of Middle East grooves. As rich as he is in musical pedigree he is equally the same in humanity: This man’s time will truly come,” Macdonald concluded.

Unlike many of today’s popular acts and recording artists, Chris Darrow established a reputation and telegenic connection to viewers, the music community and print media in the late '60s and early '70s long before the MTV world.

Chris was even quoted with Duke Ellington in Playboy magazine for their 1968 Jazz and Pop Poll issue story by writer Nat Hentoff.

Darrow was all over the US TV screen 1966-1972.

One week he’d be on The Steve Allen Show with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and author Gore Vidal, then The John Davidson Show with comic Avery Shriver and Lenny Bruce’s mother, Sally Marr. Three appearances on Playboy After Dark with Linda Ronstadt, John Stewart and The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and a Tonight Show With Johnny Carson, sharing the bill with writer Truman Capote and comic Red Buttons.

Then on the TV tube again on The Everly Brothers TV program with Ronstadt and Molly Bee, veering back to a Tempo show with Nancy Sinatra, Donovan and a very juiced out actor, George Jessel, hosted by Stan Boorman. J.D. Souther was on the program playing drums with Bobby Doyle.

Darrow’s mid and late sixties television credits go on forever: American Bandstand, Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, Steve Allen, Mike Douglas, Boss City, Groovy, and one of his best bookings, a memorable Hollywood teen music dance show, Ninth Street West, with hosts Sam Riddle and Kam Nelson where Chris and Steven Darrow guested with Brenton Wood and his son Tremail, and Canned Heat’s Bob Hite and his parents.

He also appeared on a long-forgotten LA area psychedelic/pop music TV program that current Yoko Ono publicist Elliot Mintz hosted, Head Shop, with actor David Carradine and his girlfriend, the actress Barbara Hershey.

“While playing on the Woody Woodberry Show on TV I got a chance to sit in with the house band on violin,” enthused Chris. “I was a big fan of the great jazz guitarist, Django Reinhardt and his violin playing compatriot, Stephane Grappelli. Joe Pass, the guitarist, was the greatest, living exponent of Django’s style. Ray Brown was the bass player, Earl Palmer, the drummer and Mike Melvoin was the pianist with the group.

“It was a thrill to just be in the room with these great musicians, let alone get asked to sit in. Later on after everyone but the technicians had left, James Brown was to film a segment for a forthcoming show. He had a 12-piece band with strings and two drummers. I sat in the audience bleachers and watched a full, half-hour James Brown set, complete with an interview. It was an experience I will always cherish.” Darrow gushed.

In 2019 I emailed Darrow to comment on his pivotal and game-changing work with Linda Ronstadt during 1969-1974.

“Jeff Hanna and I left the Dirt Band to start our own country-based band, which we called the Corvettes,” Chris reflected.

“John Ware, an old friend from college, became the drummer and John London, from Lewis and Clarke Expedition, played bass. London was Mike Nesmith’s best friend and this led us into a record deal for the legendary Dot Records label with Mike Nesmith as producer. We did two singles that failed to chart and our future was uncertain.

“Linda Ronstadt had just had a hit with Mike’s version of Different Drum, which had come from a Greenbrier Boys record with John Herald on vocals. She needed a band pronto and asked if we would back her up. We asked to keep our identity and we performed a song per set as the Corvettes.

“Jeff decided after a while that he wanted to return to the Dirt Band and we replaced him with Bernie Leadon. This was a great band and really set the tone for the country-rock period of Linda’s career.

“My first meeting with Linda Ronstadt and her then producer, Nik Venet, came while doing Dick Clark’s American Bandstand with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. She was singing her follow up to Different Drum, John Herald’s High Muddy Water. I fell in love with her deal immediately and, little did I know, that I would work with them both later on in the future.

“My stint with the Corvettes eventually led us to become Linda Ronstadt’s band,” Darrow underscored. “This was after poor sales on our Dot Record singles that were produced by former Monkee, Mike Nesmith. Linda needed a band, we needed jobs. I had always been in my own bands before. Suddenly, for the first time, I was an instant sideman for an established artist. John Stewart saw me with her and asked me to go on the road with him as well. So I was touring with both of them at the same time.

“While in New York in 1969 and staying at the Chelsea Hotel, I saw Peter Asher checking in to the hotel. He had just left Apple records and was in transit to take over the role of A&R director at MGM records.

“I asked him to come to the Bitter End and see the show. It turned out he was a real Ronstadt fan and loved the show and the band.

“He asked if he could produce the Corvettes for MGM. We were stoked, but by the end of our stint in New York, Bernie had been asked to join the Flying Burrito Brothers, and John and John were recruited by Mike Nesmith for his First National Band. I was left to eventually become a solo artist and soon signed with Fantasy Records.

“While working with Linda Ronstadt I had been spotted by John Stewart, who wanted a multi-instrumentalist for his band. With Linda, I was performing a Cajun tune called ‘Alligator Man,’ which was always a crowd-pleaser. I continued to perform this song with John, which led me to my meeting with Doug Kershaw.

“John was performing at Doug Weston’s Troubadour and the band was Russ Kunkel, drums, Arnie Moore, bass, Loren Newkirk, piano and myself on guitar, slide, dobro, mandolin and fiddle. One night Kershaw came into the club. John called Doug up on stage to sing with us. He did ‘Louisiana Man’ and I instantly fell into his brother’s Rusty harmony part. He kept looking over at me and wondering how I knew the song.

“My mother Nadine was a big Kershaw fan and was in the audience a different night with my sister Liz. I was going over to their table to watch the show when Doug called me up on stage.

“He handed me his fiddle and picked up his accordion and said, ‘Let’s play.’ I was stunned and excited at the same time and we played an impromptu fiddle and accordion duet, which rocked the house. It was probably the proudest moment of my mother’s life,” exclaimed Chris.

In 1970, Darrow was asked by John Stewart to introduce him to Peter Asher, who then produced Stewart’s Willard album.

As a songwriter, bandleader, record producer and fan, Chris Darrow gets excited by a good tune.

“I’m a song guy, by that I mean I love good songs and try like mad to search them out,” he muses. “I feel that much of my contribution to the various musical aggregations I have been with was the songs that I brought to the table. Much of the Kaleidoscope and Dirt Band stuff came from my record collection or my pen.

"In 1970 while playing with Linda Ronstadt, she and I went on a song search for her next record. John Boylan was her producer and boyfriend at the time. We spent a couple of days in Woodstock at the Mill Stream Inn, looking for material.

“One evening Maria Muldaur came by and sang a song that just nailed both of us. It was a song written by Anna McGarrigle of the McGarrigle sisters. The song was ‘Heart Like a Wheel.’

“My band the Floggs had done our own versions of Betty Everett’s ‘You’re No Good’ and Smokey Robinson’s, ‘Tracks of My Tears,’ two songs that I dearly loved. We added those to the list and I couldn’t resist suggesting ‘Dark End of the Street,’ the classic James Carr song of adulterous love and the first collaboration of Dan Penn and Chips Moman. It might be my favorite song.

“When we returned from our New York sojourn, neither of us could wait to suggest these songs to Boylan. He didn’t like any of the ideas that we had come up with, so I exited. Too many cooks in the kitchen, I guess.

“However, I did continue to play for Linda. In wasn’t until 1974 that she finally got to record these songs and all but one was on the same album, Heart Like a Wheel. ‘Tracks of My Tears’ was on the follow-up record, Prisoner in Disguise. Peter Asher had become her producer and the rest is history.”

There’s a new documentary Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice, produced by James Keach, directed by Jeffrey Friedman and Rob Epstein that premiered in 2018 at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2018 and released theatrically in September 2019.

Chris Darrow wasn’t interviewed for the movie.

Darrow is heard on the spring, 2004 CD reissue Moogy Klingman assembled on Moogy Music, Take Your Place in the Freak Parade, a re-release of the 1969 Music from Free Creek sessions that included Keith Emerson, Dr. John, Linda Ronstadt, Mitch Mitchell and Chris Wood. Chris is on the Ronstadt’s tracks “He Darked The Sun” and “Living Like a Fool” with Bernie Leadon and Red Rhodes.

2007 brought out the release of two musical anthology CDs that feature songs from Darrow’s past. The first, Creative Outlaws: US Underground 1962-1970, includes a Darrow original, Keep Your Mind Open, by the Kaleidoscope. It includes Jimi Hendrix, Country Joe and the Fish, the Fugs, Canned Heat, and Tiny Tim.

The second, Country and West Coast: The Birth of Country Rock, houses another Darrow-penned tune, “Beware of Time,” by the Corvettes. This CD spotlights the Everly Bros., the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Bros., Gram Parsons and Gene Cark among others.

“The last gig I did with the Dirt Band before we broke up was with the original Poco, then called Pogo, at the Troubadour in Hollywood,” recalled Darrow. “I had always loved Richie Furay’s voice in the Buffalo Springfield and Randy Meisner from back in the Poor days. But it was George Grantham, the drummer who held that band together with his tight style and high harmony singing. Jim Messina and the fabulous Rusty Young rounded out the early lineup.

“I later was asked to audition for the Loggins Messina Band after Richard Greene left the group later on in the seventies.

“This period led me to play with many artists, both on stage and in the studio. I did this until I got my first record deal as a solo artist. Arnie Moore, the bassist in John Stewart’s band, was also touring with Hoyt Axton and suggested that I become the replacement for Hoyt’s guitarist, the legendary Bruce Langhorne, who was leaving the band to devote himself to movie sound track work.

“So, I joined up with Hoyt Axton during the recording of the Joy to the World album. The record featured ‘Joy to the World,’ the title song, ‘Never Been to Spain,’ both covered by Three Dog Night, and ‘The Pusher,’ made famous by John Kay and Steppenwolf.

“One of the peripheral benefits of being a traveling musician is not only the scenery and travel itself, but also the chance to hang out with some great people and fabulous musicians,” observed Darrow.

“Often you become roommates with your traveling buddies and a real camaraderie can develop. It seems like I got to room with a lot of great drummers…. Russ Kunkel, David Kemper, Mickey McGee and the great Jerry Allison drummer for the Crickets and the husband and co-writer of ‘Peggy Sue.’

“Buddy Holly had been a huge influence on me musically and, like JFK’s death, I know exactly where I was when I heard of Buddy’s death. So getting to hang out with a hero of mine and getting to know ‘JI,’ as he is called by his friends (stands for Jerry Ivan), was a great thrill for me.

“I learned a lot about how the Crickets recorded and got a few stories here and there about the old days, but it was Jerry himself who was so cool. In addition to being a great drummer, he’s also a great songwriter and a wonderful singer.

“One of my favorite memories was when JI and I were on the road with John Stewart. He and I got together after the gig to play music in our motel room, with Jerry playing guitar and singing and me playing lead. We started with Chuck Berry’s ‘Brown Eyed Handsome Man’ and evolved into a string of Cricket and Buddy Holly songs including ‘Peggy Sue’ and ‘Every Day.’ I still have a cassette tape that I made that night,” rhapsodized Darrow.

“While working on an album by Sammy Walker, produced by former John Stewart producer, Nik Venet, I met a great guitar player named Billy Walker. He had just moved out to L.A. after being a successful Nashville session man.

“Billy liked my playing a lot and suggested that I work on a project that his friend Keith Allison was working on. Keith, the bass player for Paul Revere and the Raiders, was scoring a new Peter Seller’s 1972 film directed by Rod Amateau, Where Does It Hurt. Rod directed the television programs The Bob Cummings Show, The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, and The New Phil Silvers Show.

“The band for the movie was Keith, Billy, Glen D. Hardin, Sonny Curtis, me and ... Jerry Allison! I was playing with the Crickets on a movie soundtrack. I just couldn’t believe it. What a thrill and a chance of a lifetime for a guy like me. The movie was not a very successful, but once in a while, I see it on cable TV.

“Jerry had once taken me backstage at an Elvis concert while he was performing in Chicago. That’s where I first met Glen D. Hardin, who was Elvis’ piano player. Never got to meet Elvis, however, I was in the band room; he was just on the other side of the door!

“Around the same time I got to know Gram Parsons a little bit,” revealed Chris. “He and Bernie Leadon would come out to my house and visit. The Burritos even did a concert right across the street from my house; I designed the poster for the gig. Gram had a mentor from the East Coast who was teaching in Claremont at Pomona College,” disclosed Darrow. “His name was Jett Thomas.”

“I think that country-rock was a West Coast phenomenon and that the bands were the originators, not the individuals. The East Coast solo artist was a different breed from the West Coast collaborative unit. Most of the situations that arose in the West Coast were band situations and whether there was strife or not, the element of the band usually prevailed. Guys like Gram Parsons were much more self-directed and solo oriented than most of the West Coast personalities that worked with him. Chris Hillman has always been a good team player. Bluegrass training!

“What I’m saying is that country rock did not sprout out of the head of Gram Parsons and everybody else followed. He was a talented guy but I am one who refuses to put a single name to the father of this genre.

“The fomenting of this music started early in all our heads and each opportunity to express it was taken. A steel guitar is not the only criteria for country-rock music. Clarence White invented a device to play the electric guitar like a steel guitar. He and Gene Parsons developed the Parsons/White Pull-String, eventually called the StringBender, and then renamed the B-Bender, which bends the second string in the same manner as a steel guitar.

“It is a hard style to play and only a handful of musicians have mastered this technique. I had a chance to play in his band at the Ash Grove a month before his untimely death,” Darrow sighed.

“In 1971 after I did my debut solo album Artist Proof for Fantasy Records produced by Denny Bruce in Hollywood at Crystal Sound Studios, I went to England in 1972 to record my second album, Chris Darrow, for United Artists Records. In finding musicians of like minds, I was drawn to the Fairport Convention and was very happy to have Dave Pegg and Dave Mattocks as a rhythm section for a couple of my tunes.

“Gus Dudgeon, then producer of Elton John, was very helpful in us getting to record at one of the world’s finest recording studios, Trident Studios. We were very fortunate to have David Hentschel as an engineer, who had done great work for Elton John. The band Hookfoot, with Roger Pope, on drums, and guitarist Caleb Quaye, provided the R&B and rock roots that I was looking for. Clive Chaman, bass player from the Jeff Beck Group, rounded out that rhythm section.”

“I saw Ritchie Valens a month before his death in Pomona,” reflected Darrow, “at the Rainbow Gardens, an all-wooden building, with a low ceiling that was just south of the YMCA in Pomona, California,” he remembers. “It later was to burn to the ground. I was from a mixed race white and Hispanic neighborhood in Claremont, called Arbol Verde. My best friend Roger Palos, was Mexican, and he and I were both learning to play guitar and we would sing together a lot. The songs that we learned that were not from the folk music genre, were popular songs mainly by Elvis Presley, the Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly, and Ritchie Valens. For some reason our favorite song of Ritchie’s was not ‘La Bamba’ or ‘Oh, Donna’ but ‘Hi-Tone.’ We just loved that song.

“I was 15 and in the ninth grade and was not allowed to go out many places by myself at night. I was attending a private school in Claremont, called Webb, which had sons of famous people in my class. Chris Mitchum, son of Robert, Chris Reynolds, his father owned the LA Angels professional baseball team, Tom Mitchell, whose father invented the Mitchell 35mm movie camera and Bob Washburn, whose dad was the head of 7UP. Since I wasn’t driving yet, it took a lot for my folks to let me go into the dark part of Pomona to see a rock and roll show in late 1958 or early ’59. My parents weren’t square but my mom always worried about me.

“I went alone to the concert, as it was kind of a pilgrimage for me. Since I really identified with the Mexican culture and wasn’t afraid, I couldn’t wait to see one of my main men, Ritchie Valens. After all he was only 17 and not much older than Roger and me. I wore my bright, red corduroy coat with silver buttons that my Grandma Darrow had made for me that Christmas. I also wore white bucks, white pants and red argyle socks. I looked sharp!

“I’m not sure who the house band was, but it could have been Manual and the Renegades, or the Mixtures,” Darrow ponders, “’cause they both used to be regulars at the Rainbow Gardens. I was very excited and hadn’t been to too many concerts before this. I listened to a lot of radio at the time and because of the heavy Mexican influence in my life, I got turned on to KDAY with DJ Art Laboe, who would broadcast live from Scribner’s Drive-In, and Ol’ HH -Hunter Hancock- who had a great show called ‘Harlem Matinee.’

“These were the guys that the Mexicans listened to on the radio. I was also into KFWB, with Al Jarvis, Bill Balance and Ted Quillan, and Dick Hugg “Huggy Boy” on KGFJ. He was on so late at night that I would have to listen to him under the covers of my bed in my room. So what is now called Doo-Wop was big with me, as well as the white-dominated music so prevalent on major radio stations of the time. The Oldies but Goodies albums by Laboe on Original Sound were right up my alley.

“I was really into dancing at the time and had a chance to dance a few numbers with some strangers at the show. The opening act for Ritchie was Jan and Dean; possibly really Jan & Arnie. In those days no one had their own bands and acts would use house bands as their own. Either the band didn’t like Jan and Dean or they just didn’t care. Before they could get through the first song, which sounded awful, Jan stopped, ran off the stage followed by Dean, and plowed through the locked stage door and out into the night. Jan just kicked it open like some thug in a movie. I was so shocked and dumbstruck by this. They never came back.

“After the commotion died down and it was time for Ritchie to come on,” marvels Darrow. “He whirled in, probably from some other gig earlier that night, and I went right up next to the edge of the stage. He was a pretty big guy and loomed on-stage with a graceful power. He was not overtly hard core in his presentation but was very soulful and I ate it up. There was a tenderness and sweetness about him, even as he rocked. The house band knew his stuff and did a great job on the songs. He did ‘La Bamba’ and ‘Oh, Donna’ and even played my favorite song, ‘Hi-Tone.’

“The house band played on to people doing the Stomp and I was awarded a prize for being one of the five best- dressed guys of the night. A perfect end to a perfect evening.

“I read somewhere that Frank Zappa saw Ritchie in Pomona, so he was probably there, too. A month after the gig I was at school and heard about the deaths of Ritchie, Buddy and the Big Bopper. I was crushed and went off by myself and cried like a baby. It was the first time I remember crying for someone who had died. Ritchie Valens and Buddy Holly were like gods to me at the time and could do no wrong. It was one of the great losses in rock and roll history. It wasn’t too long before we lost Eddie Cochran in a car accident. That event also caused bodily injury to another unsung hero, the great, Gene Vincent. Later in my life I had a chance to meet Gene and had the honor of playing on one of his last albums.”

In 2012 I spoke with Darrow one late evening. He’s had an interesting musical ride to get to the melodic moments he shares with the globe.

“Since I don’t read music, I have had to learn by ear. Most of my early influences were self-taught or ear trained. Many of the blues and folk musicians learned to play as apprentices to someone else. The folk process not only passes from person to person but also through other mediums, i.e. radio and records. A new record could be played over and over, absorbed and injected. Records became my main teacher and I became a multi-instrumentalist by wanting to sound like the records I listened to.

“I figured if they could do it, so could I. Each instrument is like a voice to me and after all this time I have developed a degree of proficiency on a number of instruments. I am still learning all the time and, like Ellington, I hope to be doing better every day, every year until the day I die.

“I played fiddle on the soundtrack Jack Nitzsche produced for Greaser’s Palace a film directed by Robert Downey, Sr. Nitzsche once told me, ‘Oh, I get it, the reason you play all those instruments is that you are really a composer. It gives you a way of talking to other musicians about what you want from them.’ Sometimes it takes other people to tell you about certain aspects of yourself.

“The team ethic for music that I aspire to comes from my early love of baseball and my hero, Gene Baker. Gene was an all-round player who could play any position and had a respectable .278 lifetime batting average. He played for the minor league L.A. Angels in the Pacific Coast League and was the first black man to play for the Chicago Cubs in the major leagues, where he won a Gold Glove award. I wore his number 9, same as Ted Williams. Gene Baker wasn’t a superstar but he was always in the game. That’s my kinda guy,” reinforced Chris.

“I grew up in a family where religion was part and parcel of what you did and all religious customs were recognized as equal. As an art student, my father studied with a great, Japanese painter, Sueo Serisowa, so Buddhism and, especially Zen, was part of the parlance of everyday life. We went to Sunday school at the local community church, yet there was a Christian Science essence coming from my father’s side of the family, my grandmother, Ruth Darrow. After reading Somerset Maughm’s The Razors Edge at the age of fifteen, I realized that the spiritual search was the most important part of life and I chose to seek my own, personal path. For years I read about the world’s great religions, waiting for the calling from somewhere to guide me to a discipline with which to follow.

“In 1968, while in the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, I worked on Paint Your Wagon. It was filmed in Baker, Oregon, yet it was supposed to be the late 1840’s in California. Hippies, with long hair and beards, were hired as extras to make the film look authentic. Most of the extras were from Portland, Oregon and amongst them was a great jug band called the ph Phactor Jug Band. They had been a part of the early San Francisco pre-hippie period in Virginia City, Nevada with the Charlatans and the Warlocks.

“Their jug player and singer, Steve Mork, and I became fast friends. There was a glow, an aura about him, that appealed to me and I asked him what it was. He told me that he was a member of SRF, the Self-Realizaton Fellowship, founded by yogi, Parmahansa Yogananda. I had read his book, Autobiography of a Yogi and knew a lot about him. This eventually led me to take the lessons and learn the meditation techniques of Yoganada. His non-sectarian approach and east meets west comparisons appealed to me, so I became a devotee. The yogic attitude is so much counter to the way the music business works, it’s a wonder I’ve made it this far.

“In a world of ego and dog eat dog, the yogi strives to act as a cool character, a dispassionate advocate. I believe in the golden rule and a non-confrontational way of living life. It has worked for me as a human being but certainly against me in the “me first” attitude of show biz. As a young man, I was naïve to much of the machinations of how people make it in the world of popular music and, as a result, I thought that one just had to be good and the rest would follow. I was sure wrong.

“I have had a wonderful life as a musician and have made many, good, lifelong friends. However, there is a competitive, ruthless quality that comes out when people get close to the Golden Ring. Humility goes out the window, friends become enemies and one starts looking over the shoulder for the big stab. I’ve seen it so many times that I expect it more than not. So in response, I have chosen to live an isolated, quiet existence and now only work with old and trusted friends. I’m not paranoid, it’s just that I now have a way I like to work and find that stress and strain only gets in the way of the music, which of course, is the most important part.

“There is an ethic in music and songwriting that I follow. There must be a redeeming characteristic or moral to a song or piece of music. If it doesn’t have this, music does have the power to corrupt. I call this the morality of music. Popular music can be damaging if these attributes are not in line. Words are things and they can pack a punch. The sound and tonality also play a large part in this. The eastern religions look for a unity, a compassionate look at the world. I hope I can convey that feeling of sincerity in the music that I write and produce.

“In this post 9/11 world, the need to stay away from pointing of fingers and hatred is paramount. After the twin towers atrocity, I emailed my friends to remember peace and love. The more one retaliates, the more retaliation will occur. I am more afraid of our national reaction than I am to those from the outside. There is something in the air, some of it is good and some bad. The good is that the true evaluation of what's really important can come back into light. The bad part is the fomenting of hatred towards our fellow man. It makes me look at what I do in a different light. The compulsion of solving the problem with a song, a novel, a movie, etc. is in the mythology of our lives. Plato, Socrates, Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, and the like, all had their chance. No deal, they couldn't solve the problem, they could just articulate it. I hope it's not too late for us, as a world, to at least stop such ridiculous behavior and tend to one another's needs,” he concluded, eluding to daily threats and ecological woes we all face.

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 16 books. His literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018. It was nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections Awards for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research.

During November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz. In late 2020 Sterling/Barnes and Noble will publish a Kubernik title on Jimi Hendrix.

For 2019 Kubernik penned a guest essay for The National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. on the landmark album The Band. In November of 2006, Harvey was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.

Kubernik’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown appears in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett published in 2019 by Oxford University Press. Brackett is a Professor of Musicology in the Schulich School of Music at McGill University in Canada. Harvey joined a lineup which includes LeRoi Jones, Johnny Otis, Ellen Willis, Nat Hentoff, Jerry Wexler, Jim Delehant, Ralph J. Gleason, Greil Marcus, and Cameron Crowe.

Kubernik’s 1996 interview with poet/author Allen Ginsberg was published in Conversations With Allen Ginsberg, edited by David Stephen Calonne for the University Press of Mississippi in their 2019 Literary Conversations Series. Harvey is featured in the 2014 book by Jeff Burger on Leonard Cohen Interviews and Encounters for Chicago Review Press. This century Kubernik wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century.

In 2019 Kubernik served as a Consultant on a new 2-part documentary on the musical legacy of Laurel Canyon. Alison Ellwood is directing the documentary who helmed the authorized History of the Eagles. Debut broadcast date is first quarter 2020 on EPIX Television.