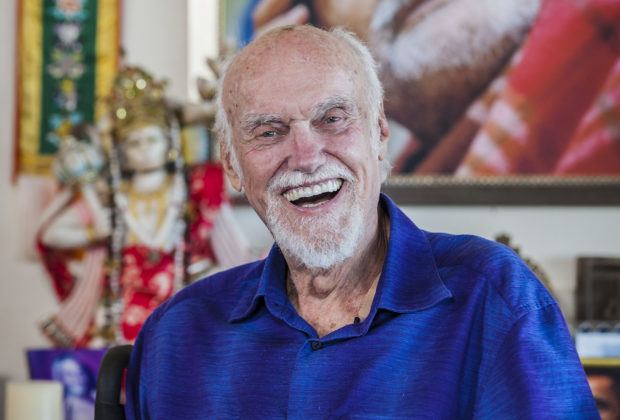

The American spiritual leader, psychedelic explorer, author, deejay, counterculture icon Ram Dass has died at age 88 in Hawaii.

During late 1996 I conducted an interview with Ram Dass one evening scheduled for HITS magazine. We talked in the lobby of the Sheraton Hotel in Universal City, CA.

Ram Dass relished the opportunity to discuss his life and work in the FM radio universe, as well as a retrospective look back on the roles music and rock concerts have done influencing his life journey.

Richard Alpert (aka Ram Dass) was born in 1931. His father, George, a lawyer, helped found Brandeis University and was President of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad.

Ram Dass studied psychology, specializing in human motivation and personality development. He received an M.A. from Wesleyan and a Ph.D from Stanford. He then served on the psychology faculties at Stanford and the University of California, and from 1958 to 1963, taught and researched in the Department of Social Relations and the Graduate School of Education at Harvard University. During this period, he co-authored (with Sears and Rau) the book Identification and Child Rearing, published by Stanford University Press.

It was in 1961, while at Harvard, that he collaborated with Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, Aldous Huxley, Allen Ginsberg and others to pursue intensive research with psilocybin, LSD-25 and other psychedelic chemicals. Out of this atmosphere and research came two books: The Psychedelic Experience (co-authored by Leary and Metzner, and based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead published by New American Books); and LSD (with Sidney Cohen and Lawrence Schiller, published by New American Library). Because of the controversial nature of this research, Ram Dass was dismissed from Harvard in 1963.

Ram Dass continued his research under the auspices of a private foundation until 1967. In that year he traveled to India, where he met his Guru (spiritual teacher), Neem Karoli Baba. Ram Dass studied yoga and meditation, and received the name Ram Dass, which means “servant of God.” Since 1968, he has pursued a variety of spiritual practices, including guru kripa—devotional yoga focused on the Hindu spiritual figure Hanuman; meditation in the Theravadin, Mahayana Tibetan, and Zen Buddhist schools; karma yoga, and Sufi and Jewish studies.

Over the last third of a century, Dass hosted a series of talk radio shows on both the FM and AM bands. Ram Dass has always had a high profile in the FM world, especially on the Pacifica and National Public Radio outlets. In the late nineties, one was titled Here And Now With Ram Dass From The Heart.

Ram Dass’ legendary book, Be Here Now, is now in a 34th printing with 1.2 million sales. I first picked up Be Here Now in the very early 1970s at the now defunct LA Free Press Bookstore on Fairfax Ave. when I was staying one night with Bob Sherman and his parents at their duplex on Genessee Ave. in West Hollywood.

Ram Dass has always been entwined to music. In college—he holds a Ph.D. from Stanford—he listened to the jazz of Jimmy Archey and The Riverboat Five, and his running buddies in the jazz world included Maynard Ferguson and Paul Desmond. In the early '60s he actually did a week-long stint doing monologue at the Village Vanguard club, initially slotted to open for Charles Mingus, and later sharing that booking with Ornette Coleman.

Ram Dass attended The Monterey Pop Festival, frequented the Fillmores, Avalon Ballroom and Family Dog concert halls. Early in their formation, Ram Dass, with a loyal following of his own, opened for The Grateful Dead, and over the years he was actually a board member of The Dead’s Further Foundation. His piece, “Jerry’s Gone,” appears in the new book, Garcia: A Grateful Celebration. In late 1996, he also shared a panel discussion in Germany with The Beastie Boys’ Adam Horowitz and The Dalai Llama. Earlier in the 1990s, Peter Gabriel collaborated with Ram Dass in a service concert, and later Ram Dass visited Gabriel’s studio in England.

It was the book The Psychedelic Experience on The Tibetan Book Of The Dead, that had a profound influence on John Lennon and The Beatles’ composition, “Tomorrow Never Knows,” the first song recorded for the Revolver album.

Asked his favorite albums digested during psychedelic experiences, Ram Dass during this interview immediately replied, "Sgt. Pepper, early Bob Dylan, and Miles Davis’ Sketches Of Spain.”

Ram Dass lectured and taught throughout the world. In 1978, he co-founded the Seva Foundation, an international service organization working in public health and social justice in communities. He is also an active board member of the Social Venture Network, a group of successful business and social entrepreneurs (including Ben & Jerry’s, The Body Shop, Inc.).

In 1974, Ram Dass created the Hanuman Foundation, which houses hundreds of his lectures and tapes while also promulgating spiritual awareness and well-being for people living in Western cultures. Projects developed under its aegis included the Prison Ashram Project, designed to help prison inmates grow spiritually during their incarceration, and the Dying Project, conceived as a spiritual support structure for conscious dying. It is now called The Ram Dass Tape Library Foundation. (415) 499-8581. Ramdasstapes.org.

This conversation is the unabridged and unedited version culled from our complete 120 minute interview session in the San Fernando valley. Ram Dass asked nothing be censored or edited.

In February 1997, Ram Dass experienced a stroke, which left him with problems of expressive aphasia and partial paralysis. The aftereffects of the stroke made it necessary for him to postpone plans for this radio program, but he was able to resume his other teaching commitments, and used the experiences attendanton his stroke to explore more deeply the spiritual dimensions of suffering and the nature of aging.

Ram Dass continued the unfolding process of recovery and rehabilitation. The effects of his aphasia made his speech hesitant, but the understanding and humor behind his words did not changed. It was just a more patient way of speaking and listening—we “all walk a little slower,” and appreciate the spaces of shared silence.

2002 brought the US theatrical release of a heart-warming documentary on Ram Dass by filmmaker Mickey Lemle, Fierce Grace, that continues to pack movie houses domestically. “Equals any transcendent moment you’re likely to find in a fiction film, a novel, or a ‘manual for conscious being.’” Michael Almereyda, New York Times.

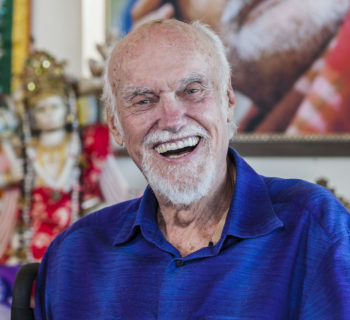

In our 1996 hotel lobby dialogue at the time, Ram Dass approached me with a hug and a warm smile. In our earlier phone call getting the time secured, he mentioned he was most happy to participate in a music-driven conversation.

“It’s groovy to talk to a real rock & roll guy,” was his initial greeting. Ram Dass also gave me some life and career observations/instruction during our two-hour chat, which I feel can translate and help others reading this text. Ram Dass was a very generous individual. I am most blessed.

Q: Good evening, Ram Dass.

A: Namaste, Friend. (This is a greeting used in India. It means, “I honor the God within you,” or “as Ram Dass puts in, “I honor the place in you where, when you’re in yours and I’m in mine, there’s only one of us.”)

Q: How did the concept of your current radio program begin?

A: It started because I realized that I was getting more and more letters from people saying, ‘When are you coming back to Cleveland?’ ‘When are you coming back to Florida?’ And I’m 65, and I thought, ya know, maybe I don’t want to travel as much as I was doing for 25 years. As recently as three or four years ago, I was doing 60 cities, one every night for four and a half months. And that’s just surrender. A lot of schlepping. I love traveling, but I realized I might want to change my game plan a little bit and use technology to connect with people.

It also came out of the fact that I tried television stuff and found it was very ponderous to work with, because of the cost of it, the technology of it and I had some tough rounds with that, so radio seemed like a possibility.

Then the issue was AM or FM, and FM to me is like preaching to a choir. It doesn’t have the challenge of broadening the audience like an AM station, and I’ve just completed doing a few weeks of ‘pilot shows on both FM (KPFK, 90.7) and AM in Santa Rosa (KSRO, 1350). The shows, which are three-hour shifts, are titled “Here And Now With Ram Dass From The Heart”.

Q: What has happened since you’ve done these initial shows? In the last 30 years you have had a radio presence, a connection with the Classic Rock community, and books like your “Be Here Now” are in a 34th printing and have been read by millions of people, now published by Crown.

A: A lot of things have happened and it’s been fascinating, because the AM experience has been entirely different than the FM experience. The FM experience, because I was doing a midnight show on a program, “Something’s Happening” that (KPFK-FM air personality) Roy Tuckman has been running for 15 years with my tapes and Alan Watts’ tapes being played regularly for years, my audience is gathered already, so I am inundated with phone calls, and 11 call lines are busy the entire shift. When I stop, they are still busy. It’s very loving and a warm hangout.

Q: Do you ever feel you are preaching to a converted audience and listenership already? From the air-checks I heard, people and callers are still asking personal and important questions.

A: They still have incredible questions. But it’s a different level of questioning. It’s ‘We’re all on this journey together and we are running into this.’ It’s like you meet pilgrims on a path in The Himalayas and somebody says, ‘Hey, what do I do when I get to that corner?’ ‘Well, you curve here.’ It’s more that type of thing.

Q: Is radio a very intimate experience for you?

A: Very intimate. I do an awful lot of work on the telephone. I work with dying people. It’s part of my shtick. I don’t get paid for it. It’s stuff I love doing and I’m able to tune in through listening into somebody really deeply and put myself out of the way and just go way, way in to hear what single sentence or what single thing they are really saying, not just ‘saying’, saying. And it’s interesting, because it is like pillow talk. It’s a form of making love, actually. It’s very intimate because we get into shared psychic experiences, shared spaces of awareness. The predicament with AM is that is that you are locked into time frames so you are constantly dealing with ‘2 more minutes’ or ‘3 more minutes’, hard cut, ads coming up, read this, do this, and it’s very hard to stay in a deep enough telephone conversation and it’s a whole new skill for me.

When I do lectures, I like the lights on because I want to see the audience. For radio, I need the telephone call-in, it’s like talking to a white light. If I have a telephone caller, then the way they phrase their words leads me to the metaphors I use. When I do lectures, I allow people to tape them, spread them around. Because what I was given in India by my guru was charge nothing and the thing that bugged me was when I came back to the West, I was renting halls, advertising, travel, you’re in a whole different trip. It’s not a culture where they support those kind of people. So, there I was, changing the game.

Q: You have a dozen books out, hundreds of live and studio tapes available from the Hanuman Foundation. Do you prefer the audio or print world?

A: It’s different. I think another dimension comes through with the audio. A vibratory rate, a deeper quality of my being comes through. It still leaves an imaginary space for the listener, which books also do also, as opposed to television, which keeps reducing the imaginative space. I’m finding that my tapes…people can hear me and say, ‘I listen to your tapes everyday when I drive my car.’ or ‘I listen at night when I go to bed.’ People listen to them over and over again and I realize it’s not the content they are listening to, it’s the quality of the being of the presentation that they are listening to. And that fascinates me. An old couple came up to me and said ‘you go to bed with us every night.’ I asked them ‘How many tapes do you have?” And they answered, ‘10.’ They listen to them over and over. Then I realized it’s not the content they’re listen to, it’s the quality of the being of the presentation they’re listening to. And that fascinates me.

Q: What are you offering to the radio world? Guidance? Solution? Healing?

A: It’s tricky to figure out what is being offered. I’d like to get through the stage where it’s ‘Ask Dr. Dass’. Where I know and they don’t, because that’s absurd. When I give lectures, as you know, I start out by saying ‘RAM’ is an acronym for ‘Rent A Mouth’. And you rented me to tell you what you already know, and I know you know it because when I say it, you nod. And, if you know it, what do you need me to tell you because we have to keep saying it to ourselves over and over again. So, my dream is that these (the radio shows) would be conversational, rather that I know and you don’t. Like somebody saying, “Let’s talk about this.’ ‘Okay.’ I say something and they say something back. It’s very hard because the cultural format for talk radio is asking an expert who knows. Not all, but it’s a large part.

I do a lot of telephone call-in shows and do a lot of promotional interviews when I go on lectures city by city. When I’m going on tour, I might be doing ten weeks from my home in Vancouver, or whatever. In the 70’s, I did four all night shows on WBAI-FM in New York with Paul Gorman, and those came out as a record set, actually. He’s had a regular show on WBAI for 25 years. That was a great experience.

Q: What were your radio interviews like in the Mid-to-late 60’s?

A: I remember doing the Long John Nebel Show in New York midnight to 5:00 a.m. with Timothy Leary. And, on the way down from Millbrook, we split a cube of acid, and it turned out that most of the acid was in my part of the cube. So when we got to the station, I wasn’t functional so Tim ran with the ball for a couple of hours and then I came in and took over.

That show was more focused on psychedelics in those days, and there was more ‘flower child’ mentality, more ‘Wow!’ A sweetness, a naïveté about it. Now, today, there’s more tough groundedness. My audiences are older now. In the 60’s they were 15-16, and ‘is the blue acid with the yellow dots any good?’ I mean there were those kinds of questions, ya know? And that doesn’t come up much now. In the 60’s, a lot of people called who were high on something and it was like, ‘We’re all out here together.’ It was like we were tripping together

My thing is to get out of being a guru. We’re on a journey together, and I’ll be as honest as I can about my trip and you can do whatever you want to do, but I’m going to create the space where it’s safe to be very vulnerable. That’s about drugs, sexuality, about politics, everything.

On the radio I also use some interludes from Jai Uttal; he’s with Triloka Records. He’s an old guru brother of mine for many years. I pick parts from his tape, and often the least Indian part. I don’t want to define the category too narrowly, ‘cause I’m already called Ram Dass (Servant Of God).

Q: For decades, you’ve always had a relationship to music, In your lectures, workshops, appearances at various auditoriums, and you’ve also written a very passionate eulogy to Jerry Garcia now in publication.

A: Back in the '60s and early '70s, I spent a lot of time at The Fillmore, The Avalon and Family Dog in the San Francisco area. I went to The Monterey Pop Festival and it was a time when the San Francisco sound was rock by Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Big Brother and The Holding Company, Grateful Dead. Earlier in 1963-4, I was living in Millbrook with Maynard Ferguson and Paul Desmond, and we were turning on with Paul and we would use his apartment in the city. I was going to jazz clubs with Thelonious Monk and Charles Mingus, and I hung out so I had a lot of tasty stuff with music and musicians. In my college days I was into the New Orleans sound. I’d go on gigs with Maynard and hang out with him. I did a couple of shows with The Grateful Dead, but it wasn’t the right setting for my thing, because the audience, no matter how sweet they were, basically came to have a rock concert experience.

Years ago when I was at Millbrook with Timothy Leary, he went off to India, and I was running Millbrook, and there was one night when we rented The Village Vanguard, and we put on a psychedelic show there and I was on mescaline and was the MC. Max Gordon, the owner, caught it, and said to me, ‘How’d you like to work here? Open here?’ A stand up monologue.

I said ‘great,’ ‘cause I was broke and needed the money. I was to start opposite Charles Mingus the next Monday, who then got in a fight with Max, and Ornette Coleman replaced him for the booking. The problem was, instead of my audience, there were sailors and shoe salesmen, and I started to deal with ‘sit down! Shut up! ‘Where’s the music?’ And Charlie and Max had had a terrible fight the night of the opening. Charles walked out. So Max had Ornette Coleman in place. They had come to hear Charlie. Waiters were feeding me lines. It was ghastly. And after about the sixth night Tim came into the club and I said to him, ‘What do you think?’ ‘Ridiculous.’ That’s what I think. I felt the same way. So, that was the end of my career (laughs).

Q: And in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, from what I gather, you really weren’t involved with the beat generation community, or the new poetry and performance world happening.

A: Well, I knew Burroughs of course and he and I took acid in London with some people. Gregory Corso. Allen Ginsberg. I knew them later on through Tim Leary and Millbrook. I didn’t know them before that really. When I was at Stanford in Northern California taking my Ph.d, I went there and stayed on the faculty there and went to U.C. Berkeley to teach, when I was at Stanford, weekends I would drive up to the city, and go to North Beach, and hear the beat poets, but it was so out of my world. I was a real gung high-need achieving Jewish upwardly mobile graduate student and they scared the shit out of me. Allen Ginsberg…

Q: Were you not a joiner? You always seemed removed or moved to your own beat.

A: Well, part of it is that I’m gay. And the gay community was not a community I was drawn too. And the straight community I always felt outside of. I wouldn’t go to a bar.

I mean, now, I give lectures on golf. This is very far out. I go on the links, ‘Hi. I’m Dick.’

Q: You like the game of golf? What attracts you to it?

A: I like the mindfulness of it, where my consciousness is in relationship to each swing.

Q: Did you ever think in your lifetime there would be a cable channel devoted to golf?

A: (Laughs)….It’s no longer a game for the rich and privileged. Now it’s becoming more mass consciousness.

Q: What’s the big deal about hitting a ball in a hole? You don’t have to be six foot five to play?

A: Exactly. There are certain skills that are not hard to get and after that it’s very much of a mind game. It’s where your head is at when you take the shot.

Q: So, does the hole represent completion?

A: It represents nothing to me. It’s just part of the form of the game. That’s not what other people are in it for. It’s the process and the journey. There’s a book by Mike Murphy on golf many years ago you should check out.

Q: What did you like about Jerry Garcia? As a person, not just the musician.

A: I have different images of him. Later, more recently, I was on the board of The Further Foundation with Bob Weir, Jerry and Mountain Girl. In the last few years he was complicated to work with. He drifted through. I was peripheral to his world, and he was to mine, but we would meet, and there would be a real sweetness when we’d meet backstage. Jerry was always very warm and friendly, very joining space together, but we weren’t social beings.

I met John Lennon and Yoko Ono. They came to my apartment in New York to meet me with the director, Peter Brook. We hung out and it was a very hard time in my life because I was under the influence of this woman in New York who I was studying with and she was very intrusive. John was very sweet and available and very curious and thoughtful. I found him a very loving being to be with. I loved The Beatles music. I took acid to “Sgt. Pepper.”

Q: Along with the music and albums of the 60’s, did you follow any bands or music in the 1970’s?

A: I’d go to places like The Beacon Theater to hear Bob Marley and The Wailers; those kinds of things. Reggae – I loved that stuff. Reggae, Bob Marley blew my mind. It was his thing, his message; the quality of his being. His quality of being touched me deeply. I was touched very deeply. I felt that the deeper places I would get to in my own inner work, there would be people like who were resonant like that. Those were people who were resonant in that place in myself. You meet somebody who knows your deeper truth. You’re connecting sort of behind the kind of form and façade, and even though it’s through the forms, you can feel you are meeting another mensch, another spiritual being. Marley blew my mind. Reggae music fascinated me, and also because of Jamaica and all the grass. All of that. The records were always around because everyone else around me had lots of records but…

“Ya know, you asked before…it really wasn’t the lyrics. It was not the lyrics. Most of my friends know all of the lyrics inside out, and I don’t. I was drawn to the music. I came from classical and jazz. I really liked (Bob) Dylan. He was close to Allen Ginsberg, and I was close to Allen. I loved Dylan’s music and took many acid trips listening to his music.

Q: I know we are going back 25, 28 years, but were there any specific artists or special albums you liked to trip with?

A: “Sketches Of Spain” by Miles Davis, of course. I knew Miles because I was hanging out with Peggy Hitchcock on Park Avenue at her apartment and Miles was having a scene there too.

I met him through that. That music would take me out... “Take Five” by Dave Brubeck with the drummer Joe Morello.

This is fun. Nobody has ever asked me any of this stuff. (laughs). It’s great talking to you because you’re right on the edge of it all.

Q: What a compliment! I guess I’ve arrived…

A: You have…Just keep doing what you do and it’s going to work out.

You are realizing that it’s time to let go of your anonymity. You don’t have an ego problem. A lot of it is realizing that the people out there are us not them. That’s a big secret of the thing. This is us gathering. A family. If they want to see me as him, that’s their problem. I see them as us. Had you pushed yourself earlier you would have burned. You would have crisped. I think you’ve done it very intelligently because you built a ground of connection, and in a certain way in which you’ve seen enough stuff and you’ve tasted enough, so that you’re not as vulnerable to it. Your body of work, recording and writing…It’s interesting. It’s not usual. Because the culture, the ‘People’ magazine mentality, externalizes people for that stuff very quickly. The minute a name appears immediately you are famous. And then you are gone. You’re in it for the long haul. You know when you’re ready.

You don’t have the problem like some in the music and entertainment business that many of those people know what I know but they’ve just gotten deeply caught in a system that is not creating much happiness for them. And I feel their pain, but I would say to them ‘you are really screwing yourself by making a deal with your own integrity the way you are making it in order to be successful. And that when you win you still are losing.’ And that’s a real problem. The level of prozac intake, and level of pathology of denial involved in being able to support something without integrity where you are not honoring the deeper values of wanting to have descent human relationships, and play at the edge of truth as well as you can. And the cost of that, arming your heart, and when you armor your heart you end up cut off from the light force. And then you end up in every pathology imagined. Whether it be drinking, drugs and this thing that has been created by your having to be hip and cool and sharp and with it in order to survive. And the question is: In a harsh industry can you survive any other way?

I feel that you’ve got to go very slowly and look around for other people of like-mind to give each other a little support. But it is possible. It is possible.

Don’t get psychically addicted to outcome.

I was just in Germany and I did a panel with Adam of The Beastie Boys. We were on a program with The Dalai Llama. He and I sat next together. We were also with an American guy in Germany who is playing music named Joe. Adam and I connected very beautifully, but it was with his holiness which made it fun. The Dalai Llama, along with (Czech President) Vaclav Havel in my view are the best political statements in the world today of people who are integrating passion with politics and not being blown out of the water by trying to keep those things together and The Dalai Llama and I have been together since 1967 when I first visited him. I think he’s a beauty, and he’s fun and he has a great sense of humor, and he’s a very kind and generous human being.

Getting back to the music… Sgt. Pepper. Music is a vehicle for moving consciousness and humor is a vehicle for moving consciousness. And the combination of that… Let me tell you… What I treasure in human beings is rascality. Tim was a rascal. Jerry Garcia was not a rascal. He was different. Mountain Girl once said to me, 'Jerry is like a monk. Music is his whole thing, and nothing else exists for him but that.' She was married to him. Jerry was at the mercy of a lot of people and just wanted to give everything to everybody and let them until they’d be happy to stop bothering him.

I loved The Doors. Sure…'Light My Fire.' Of course, of course. Some Eastern influences in their music. Jim Morrison was a poet…I liked the level of reality he played with. I like people pushing the edge and getting out of the linearity. I love that. And not in a kind of clever, studied way, but in an ecstatic experiential way. That’s what I love better. That’s what he tried to do.

Q: What about classical music? I seem to remember you meditated to classical music. Right?

A: Classical music is very much a part of my life, first of all. My father had a string quartet. My brother was a pipe organist and harpsichord builder. My mother was a pianist. Not professionally. And I took up the cello when I was nine in Boston. I was a lousy cellist. And as recently as two years ago I was in a trio with a psychiatrist and a meditation woman. And the three of us are lousy, but nobody listens and we’re all happy.

Q: What does playing music do for you?

A: Hmmm…Good question. I’ll tell you, if I had my choice, I’d rather be a musician than a speaker. I think words are a very, very ponderous vehicle for connecting people. And the connection happens almost immediately with music. And to me I listen to music to hear where the artist gets out of the way, and the composer gets out of the way. Like when you listen to Mozart. And you to someone playing Mozart piano concerto, it’s as if your turning in to what Mozart is listening to. You’re hearing…It’s like moving in an astro plane. It’s you directly experiencing the astro plane and the composer and the musician don’t end up saying ‘what a great pianist.’ Or ‘what a great composer.’ You end up with saying ‘what an incredible experience.’ That’s the issue of where I go for music.

A funny thing. ‘Rhapsody In Blue.’ Gershwin. My uncle was a band leader, and he was the M.C. at the Coconut Grove in Boston, which burned down, and changed everything for everybody. Because all our friends burned to death. I was like 8, or 9. Mickey, my uncle brought Gershwin to my father to get money. Gershwin was like 20… ‘He’ll never…’ That’s been a source of great humor in our family for many years. I love Gershwin. ‘Porgy and Bess.’ Things like that.

Q: In the '60s and even in this decade, are you still enjoying music, tapes, CD’s or live musical performances in your radio activities or lectures?

A: On my lecture tours, I always had music and as the years went on, the people wanted to hear me speak, the same way they go to a rock concert to hear rock. And the musicians were the warm-up act. Indian music, flutes, and the predicament was knowing their ego needs, I wanted to give them the space to do their own thing; the audience didn’t want to do that. Because the audience saw them as an interference. And they’d be talking when these musicians would play.

After a while I felt ‘this is like an immoral act that I am doing here.’ Then I started to use tapes of Bonnie Raitt and people like that. A mixture of music and tape. But I always have in my workshops people leading chanting. It’s interesting. I love gospel. Babtist churches. Going down to the Jazz Fest in New Orleans. Fantastic! Five stages! Great moments. I did a TV thing in Oakland with a thousand people about five years ago with Bobby McFerrin, Arlo Guthrie, The Oakland Choir, Mimi Farina, and I’ve been part of Mimi’s ‘Bread and Roses’ festival for a long time.

Peter Gabriel opened for me the first time we spent time together. I was in his studio in England with the water flowing underneath. He’s great. I couldn’t believe I was given the opportunity to have him open my whole series in Oakland. It was a 10 week series on service. Everybody had to do service in the community. A thousand people and this was with a four camera TV shoot. The first thing that happens is that Peter Gabriel walks on, sits down at the piano and plays, “Here Comes The Flood.” And so beautifully simple. Then we spent the whole night together in a hot tub just hanging out, and then I went to England, and spent time with him and I was almost part of something he was putting together in Spain. But it didn’t work out because of our schedules. I'll tell you, I felt his beauty, but I also felt his psychological pain. There was a lot of psychological angst in Peter. And his music is showing some of that stuff and I love him as an energy person, the quality of his being. The psychological stuff I wish he’d come up for air a little more (laughs).

Harvey, this is a gas!

See, when I give lectures, I’m getting ready in the green room, preparing, I am quieting, I am remembering my guru saying to me ‘Ram Dass speaks only about God.’ Which is fascinating to find out how to interpret that in daily life when I’m about to speak to the hospice workers of America. I’m also bringing my consciousness into deeper and deeper awareness. My game then is to get from the green room to the stage. But when you speak at The Shrine, you go through the union people who see you like a side of beef. A whole vibratory set on the way to the stage. Walking out in front of 3,000, 5,000 people you’re going to be the only thing on for the next three hours. And your consciousness is what they paid to hear. There’s money involved, and it’s not like it’s a free scene. And about charging, I only ask enough so people don’t get paranoid they don’t get ripped off. That’s very important to me. If everyone else is charging $20.00, I charge $15.00. I try to keep the prices seasonable.

I was doing a thing in New York City. My head was in the wrong…I hadn’t gotten it clean enough. I started out giving a ‘on the way to the studio time rap.’ And I guy in the balcony screamed out, ‘Ram Dass my heart hurts.’ At that moment, I saw that I could turn the whole audience against the guy, but I said to the guy, ‘If your heart hurts all of our hearts hurt.’ Let’s all take a breath and start again. He took me. He was like a gift to remind me.

On every plane you have to be clean. And I walked into a dialogue with an editor who was going to buy a book and he looked at me like ‘here is a holy person and I’m gonna really take him.’ And I said to him, ‘Bill, I think you and I can be friends, but in this dialogue I’m getting screwed to the wall and I want you to know because if I don’t be clean in my contractual dealings the karma is on my head if you rip me off.’ You hear that. I have to be clean. I can’t exploit. But I have to be clean. That’s across the board.

Q: I’ve been checking out your scene for years. You are so calm in front of a live audience. But we talked once and I was shocked to learn you get really nervous before a gig. I know as Richard Alpert, as a student, and a teacher in front of academic lectures, you were like a scared rabbit.

A: Yes. Every time I lecture. Diarrhea. I still have it.

Q: I’ve done a few readings and I like it. Any performance tips?

A: First of all when you perform in front of people, don’t be ashamed or embarrassed about it ‘cause you are. These situations awaken whatever ego is in you. Whatever residuals, even if they are residuals. The whole business of performance and being loved, being good enough, and there is a place in me that still maintains a feeling that I am inadequate to the task when I’m being called upon to perform.

Q: You once acknowledged you’re still “the neurotic Jew from Boston…”

A: Absolutely. I’ll tell you, through psychoanalysis, drugs, yoga, gurus, everything, as I’ve said in my lectures, I haven’t gotten rid of one neurosis. The only thing is that they have turned into little things, instead of big things that consume me al the time. But they’re all around and so more like residuals of things. I’m mean, I’m friendly with my anxiety, but it is there.

Now I do a lot of meditative practice in the green room beforehand. I eat and nibble lightly before, ‘cause if I get hungry if will ruin my lecture.

Q: What gives you, or anybody the opportunity to go on display, be on the radio airwaves and spiel?

A: I figure that I’ve been on a trip for about 35 years now, since I took mushrooms in 1961. And I’ve been really quite single-minded on the work I’ve been doing in myself inside. And I offer that to people. If it’s useful to them, I will work, and if it’s not useful to them, I won’t. It has to do with my functionality from where they’re standing. I may be the greatest thing since white bread, but if I’m not finding the niche in because I don’t find the metaphors to communicate, it’s no use at all. I don’t know if I’m the right thing for FM or AM radio.

Q: What is the greatest reward in the work you do?

A: I don’t go to a restaurant where somebody doesn’t come up and say, “Ram Dass. Thank you for ‘Be Here Now’. It changed my life.” That book did a tremendous thing for millions of people. In prisons in Bali there will be a copy. In Thailand a monk will bring out his copy. Musicians will come up and say, “Thanks for your books, your tapes.” It’s gone on for 25 years. So I have karma that is so good I have so much grace. I wake up everyday so blown away by the grace of my life. Now it’s two generations like grandmothers. ‘My grandmother gave me her copy.’ You realize that?

The only time I had one experience where I experienced fame and it was a drag. I was in Miami Beach and I was walking down the aisle to the stage and these women with heavy eyeliner tried to rip the buttons of my jacket. There was that hysteria. That’s a kind of a fame I don’t want. A symbolic fame. It has nothing to do with me. No empathy in it at all.

Q: Why or how did you write Be Here Now?

A: I was in India in 1968 and met my guru. One day my teacher gave me a blessing to write a book. And I said, ‘what book? I’m not writing a book.’ So I came back to the States and was no longer in academia. I had used up psychedelics as a ‘Mr. LSD Jr.,’ that was all wiped out. And I came back and didn’t know what to do. “I’ll write a book because that’s what I’m supposed to do.” So I wrote a book and sent it to nine publishers and they all turned it down.

Q: You did it yourself. That’s awesome.

A: Yes. I never had an agent after 11 books. Then we did ‘Be Here Now’ in a commune up in the mountains in Mexico and gave away the first 10,000 copies. What I did was go out on the road, and people paid a dollar and a half to come to the lecture, and a dollar of it went to this big box. It was not a book. It had a record in it and pictures. And then the orders were coming in at 50 a day and I said, ‘I’m going back to India.’ And then Crown came along and said ‘we’ll make it into a book.’

Maharaji, said, ‘Ram Dass, you should not hold on to money. It should go around you and through you.’ I’m part of a wondering sect. I give away I would say most of my money. So I live confortably in Marin County. I’m not a hardship situation at all. And since I’ve never been focused that money was real to me I never really got into it. I had no family or responsibility. And some years I was passing the hat.

Q: What about live appearances?

A: I love the chemistry of an audience. I love when we’re just in the space together. We’re so fed by the moment of being together. I’m still a generalist. However, I do get concentrated in certain areas. I do a lot more on dying. I do a lot on AIDS, and do a lot on social responsibility and business. I do a lot on the medical marijuana initiative. On hospice work and on spiritual practices. I’ll do workshops and retreats on spiritual practices. I do more now on politics. I’ll do a workshop in the hills of Santa Barbara with good level political people who really want to examine how to get out of how to be so reactive in a scene to get more reflective. Now if they are more willing to come and do that, I’m willing to come. That’s the way it works. What I like to do is take a couple of fresh areas a year and so when I look at all the invitations I get and then pick a few things I don’t know much about. It’s a challenge. And that forces me to think through and prepare a lecture for something.

Q: This is a wounded world that needs a lot of help. Are you at all encouraged?

A: It’s all very tricky. There are a couple of things that your comments raise. One is the relationship of me to the new age. What happened initially, was that when this collective awakening started to happen, and It got articulated and it started to have some juice connected with it because of the minstrels like Dylan spreading it, then all the people who wanted power glob on to it and the new age was born. Yet, I’m considered part of the new age. Or whatever that means. I’ve never used the term, and I’m not comfortable with it. When I do these Expos I don’t want to do them anymore. I still have the audience, but the cost of it in terms of guilt by association, or something like that…

See, my game is very shrewdly designed. My game is what I am marketing is my truth. And my vulnerability. I’ve taken my weaknesses and made them into my assets. By saying ‘I’m telling you my sexual story, my drug story.’ All this stuff. I’m balding. I’m getting old. I’m a fellow human being.

Getting older first of all it lets you off the hook of the rat race. It gives you a chance for a new curriculum for the rest of your life. It gives you a proximity to death that allows you to become very awake at the moment, if you use it right. If you’re not totally traumatized by it and going into massive denial. So it leads you to new options. It gives you some space because to the culture you’re becoming irrelevant and the minute you become irrelevant, you’re free. You’re free to be eccentric in ways that you weren’t before when you were mainstream. It gives you the chance to re-think, and have a new identity with that, which many people didn’t have since they entered kindergarten because they were lock-stepped all along all the way through the game. All the way through until their 55, 60. To me the demographics of the baby boomers turning 50 means that as the numbers change in society, that obsession with youth that society has had, now the numbers can re-define the mythology. See, they have the advertising dollar and the vote. And the advertisers are figuring out how to get woman over 40.

Q: What about The Hanuman Foundation and the Ram Dass Tape Foundation?

A: I set it up in 1973 to try to figure out how to do some service. And since I was a bad guy iun society since I was thrown out of Harvard for drugs, the only people I could work with were dying people and prisoners. We have a tape catalogue. The most popular titles are relationship stuff and spiritual practices is a big one. And the aging tapes.

Q: I appreciate you finding the time to speak to me. Please sign my Be Here Now book.

A: Thank you, Harvey. I’ll see you again. Namaste.

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 15 books. His literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018. It’s recently been nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections Awards for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research.

During November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz.

Kubernik’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown appears in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett published in 2019 by Oxford University Press. Brackett is a Professor of Musicology in the Schulich School of Music at McGill University in Canada.

Harvey joined a lineup which includes LeRoi Jones, Johnny Otis, Ellen Willis, Nat Hentoff, Jerry Wexler, Jim Delehant, Ralph J. Gleason, Greil Marcus, and Cameron Crowe.

Kubernik’s 1996 interview with poet/author Allen Ginsberg was published in Conversations With Allen Ginsberg, edited by David Stephen Calonne for the University Press of Mississippi in their 2019 Literary Conversations Series.

Harvey is featured in the 2014 book by Jeff Burger on Leonard Cohen Interviews and Encounters for Chicago Review Press. During 2015 the University Press of Mississippi published a Harvey Kubernik interview with D.A. Pennebaker in their book series, Conversations with Filmmakers, edited by Dr. Keith Beattie.

This century Kubernik wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century.

In 2019 Kubernik served as a Consultant on a new 2-part documentary on the musical legacy of Laurel Canyon. Alison Ellwood is directing the documentary who helmed the authorized History of the Eagles. Broadcast date is first quarter 2020 on EPIX Television.