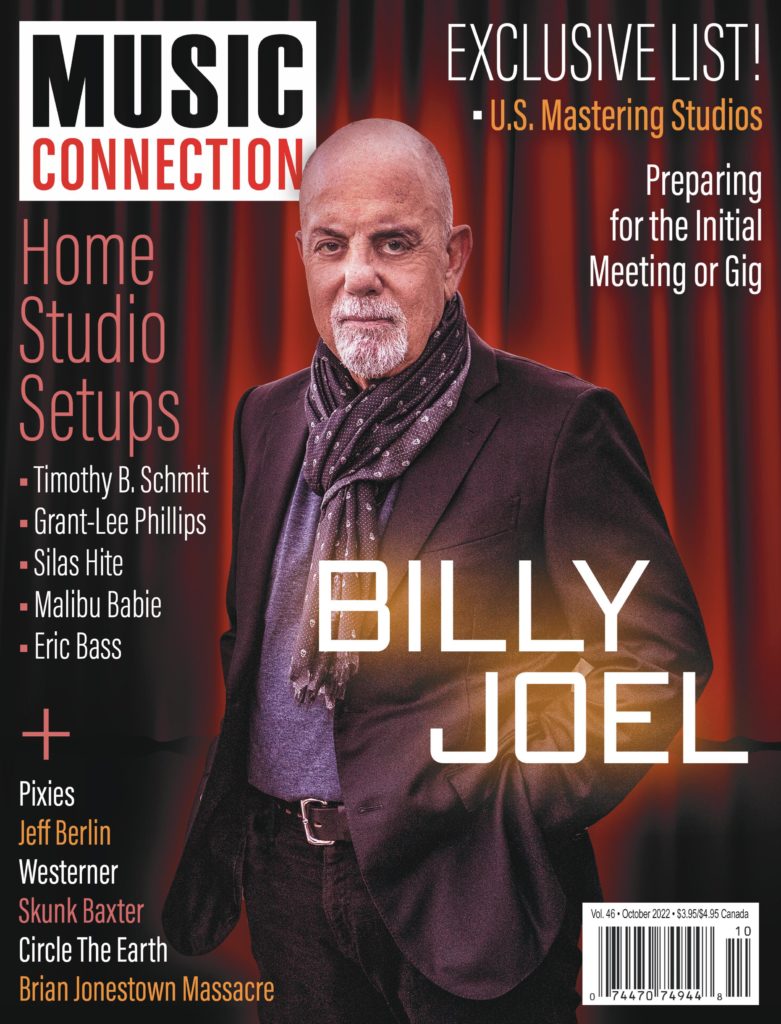

The Piano Man is still playing us a song—just a little differently than he once did. Billy Joel hasn’t released an album in 20 years, and his last was a set of classical piano compositions. He hasn’t released any new songs since “All My Life,” a one-off, in 2007—and that was his first in nearly 14 years back then. Instead, Joel, 73, has pivoted into a career as a live performer, with monthly appearances as a “franchise” at New York’s Madison Square Garden and, during the outdoor months, gigs at stadiums around the country. Nice work if you can get it, right?

But it’s not like Joel hasn’t earned his spot. He’s a bona fide—as the songs says, “Big Shot”—with more than 160 million records sold worldwide, 18 platinum or (mostly) better albums to his credit, and a ranking as the fourth best-selling solo artist of all time in the U.S. according to Recording Industry Association of America. Joel has also logged nearly two dozen Top 40 singles, and his 1985 compilation Greatest Hits Volume I & Volume II is the second best-selling album by a solo artist, behind only Michael Jackson’s Thriller. Add to that five Grammy Awards, inductions into the Rock and Roll and Songwriters Hall of Fame, the prestigious Johnny Mercer Award from the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2001 and a Kennedy Center Honor 12 years later and it’s an abundance of laurels to rest on.

But check out Joel’s still-exciting concerts these days and you know the man isn’t exactly resting on any laurels. He’s just working in the different kind of manner all those achievements allow for....

Music Connection: You had an unexpected 17 months off during 2020-21. What was that like for you?

Billy Joel: It was kind of frustrating, ‘cause I don’t like to have to reschedule or cancel. It was a two-year period where we weren’t working at all, so it was very frustrating. Musicians have to perform live. That’s what we do. And when you can’t do that, what are you doing? You’re not doing anything. You’re just sitting around twiddling your thumbs.

MC: And since the mid-‘90s you’ve been almost entirely a live performer rather than a recording artist.

Joel: Yeah, I don’t even record anything anymore. The only kind of music I write now is instrumental music for my own gratification, and there’s not a whole lot of other interaction with other musicians going on. I have two cute little girls and it’s a lot of fun, but once in a while I feel like I have to justify my existence.

MC: You play your monthly shows at the Garden and then go out and play a few stadium dates every year—kind of like a home and away series. Do you treat them differently?

Joel: Well, yeah, there’s a big difference. The Garden, even though it’s a famous venue, it’s basically a coliseum and an arena, whereas the stadiums are these outdoor monstrosities where you can have up to 80,000 people. So, there is a big difference, especially if you’re a piano player, because you’re fairly static, and when you’re sitting at a piano it’s not like you can jump around and make guitar faces.

MC: So how do you make it work in that kind of setting?

Joel: I guess because we’ve done it enough, I just talk to the audience like I’m in my living room. I have a sound man who’s been with me now for almost 50 years, so he knows how to EQ my voice so that people can understand what I’m saying in a baseball stadium. I don’t even know what they’re saying in a baseball stadium when they’re announcing the players, but he’s able to get that place to be audible for an audience. So, I’m just comfortable. I sit there and talk. I’m not Mick Jagger, so I don’t have to worry about bopping around and dancing. We’re pretty used to it now.

MC: How have the shows felt any different since coming back from the pause?

Joel: When we went to do the first gig after the Covid layoff (Aug. 4, 2021 at Fenway Park in Boston), yeah, I had a little bit of nerves. Two years is a long time for a musician to be off. You wonder, “Do I still have muscle memory? Am I gonna screw up the lyrics? Are we any good anymore?” So, it was a little nerve-wracking. But after you get that first show over with, you’re like, “Oh, I can do this. Right. I’m THAT guy.” You forget you’re THAT guy. So, it comes back.

MC: “That” guy has a pretty formidable legacy after all these years. What’s your own view of who “that” guy is?

Joel: I kinda have a split opinion about it. Part of me thinks it’s absurd; I’m 73 years old and I’m doing the same gig I was doing when I was 16! This is a job for a young person. I am now considered elderly, and I’m still doing the same crazy-ass job, so that part of it is kind of absurd. The other part it means to me is it’s wonderful. I picked a great job to have. They’re paying me all kinds of money. The audiences are bigger than they ever were. People are still coming to see me, and there’s a lot of young people out in the crowd who still know my stuff. That’s wonderful. I’m a lucky guy.

MC: Not only that, but you’ve had shout-outs in songs by Bob Dylan...and Olivia Rodrigo, among others. How does that happen?

Joel: You got me. I have no idea where it’s coming from, but I’m very grateful for it. I appreciate the shout-outs and the recognition. It’s nice to feel like you’re somewhat relevant in this day and age, ‘cause I’m a dinosaur. But I guess dinosaurs have antique value. So, it’s kind of a miracle. If anybody had said I’d be doing this at this age and have the kind of success we’re having, I’d have told them they were nuts. This is rock & roll. I didn’t cure polio.

MC: Do you ever allow yourself a moment of pride, though, to appreciate what you’ve accomplished—musically as well as statistically?

Joel: From time to time. There are songs in the show that I really like to do, which are the more obscure ones. I tend to like the album tracks more than the hit singles. I feel a certain sense of pride and satisfaction after I finish those songs. I think to myself, “That wasn’t bad. I don’t remember how I wrote it or why I wrote it, but that’s pretty good.” So that hits once in a while.

MC: Are we ever going to hear the piano music you mentioned you’re writing?

Joel: No. I try to play some of those pieces from time to time, but it kind of lays there like a lox. It’s not something people are very familiar with. I’ve tried it, but I’m not beating it to death.

MC: And you’re still not writing songs?

Joel: Not yet. I haven’t shut the door on it. I am still writing music; I’m just not writing lyrics now. I’m not writing in song form. I’m writing in a more abstract form, and I’m comfortable with it. But if I get an idea for a song I’m not gonna stop myself from writing it. I’ll do it. I just haven’t woken up recently with a great song idea. The reason I stopped writing pop songs, and songs in general, is because I felt constrained by song form. There’s an orthodoxy to pop; you’re writing inside of a box. Y’know, it can’t be too long, you have to repeat the verse over and over, you gotta have a hook, you gotta have lyrics in it, you gotta have rock n’ roll instrumentation, you gotta have bass, drums, guitar, there has to be a voice taking the lead. Then I thought to myself, “Well, why? Why? Who says I have to do this?”

MC: After writing it for so long, is it disappointing not to, or are you liberated in a way?

Joel: For me it’s liberating because I never enjoyed writing. I always enjoy having written. When I would get to the end of a song I was writing I was wrung out, ‘cause I wanted it to be a certain quality. I have high standards, and if I don’t meet those standards I’m pretty angry with myself and I’m hard on myself and I beat myself up.

I read a quote once from Neil Diamond where he said he’s come to grips with the fact that he’s not Beethoven. He’s forgiven himself that he’s not Beethoven. And when I read that, I realized I haven’t forgiven myself for not being Beethoven. I struggle and I suffer from it. So, I’m happy not to do that anymore, because I beat myself up enough during my lifetime.

MC: You have written classical music, on the other hand.

Joel: Yeah, but I didn’t record it. I actually had a classical pianist (Richard Hyung-ki) play those pieces, because I’m not good enough to play them properly. I didn’t study long and hard enough to be able to play that kind of music. I can write it, but you only write it in short shifts. You don’t sit down and write the whole thing in one fell swoop. Once in a while I’ll kind of play a little piece, but that’s about it.

MC: It’s been a long enough career that you have some significant anniversary pop up about every year. This year it’s 35 years since your groundbreaking tour of the former Soviet Union. What’s your perspective that trip now?

Joel: Well, with what’s going on with Russia nowadays, I’m very disappointed. I mean, I’m glad we did that trip. I was very proud of that trip, and I think we helped kick the door in a little bit to open it up to democratic stuff. But nowadays...I’m hoping the Russian people really get to know what’s actually happening, but I don’t know how much real information they get, because they’re kinda in a closed medianow, between Trump and what’s going on with Russia and Covid and what’s going on with the economy, this is a hard time now.

MC:As an artist do you feel a responsibility to reflect that or provide escape from it? Or both?

Joel: Well, I realize at this point I’m more a court jester than a court philosopher. There’a a line in “Piano Man” that I sing—”I know that it’s me that they’re coming to see to forget about life for a while”—and the audience applauds after that line and I realize, “Wow, they’re really here to get away from the news. They needed a break.” They wanted something to take them somewhere else, and that’s my job. I never thought of myself as having to be a socially conscious documentarian. My politics are my politics, but the music is something else.

MC: You took on that role with the Nylon Curtain album, which turns 40 during September.

Joel: Yeah, well, that was right in the middle of the Reagan era, and things were changing in America. I was very aware of it. It was baby boomer peaking time, the early ‘80s. Things did change then. I was very proud of that album. The songs seem to still resonate with audiences, and with younger people as well. I’m always amazed at how many kids are in the crowd. Here I am, I’m 73, I figure there’ll be a lot of gray hair out there but there’s a lot of kids, and they’re relating to what I’m singing about. So, it has resonance.

MC: The Stranger turns 45 this year, too. Want to weigh in on that one?

Joel:My thoughts nowadays are I can’t believe how long ago that was. I don’t do a whole bunch of retrospective on my own material. I’m not someone who sits around and thinks about the old days. I’ve got my hands full with the little ones.

MC: They’re very young, but do they keep you up on current music at all?

Joel: They love Taylor Swift. They love Olivia Rodrigo. They like what kids are listening to now, and they know a lot of the music. They kind of educate me because I don’t really listen to it, consciously. They’ll just point to me, “Dad, listen to this.” They know what I do. They like the fact I have this job. They like going to gigs and hanging out. They like the rock & roll life.

MC: Do you get inspiration from watching colleagues like Paul McCartney or the Rolling Stones keep going?

Joel: It does make me aware that it’s doable. I figure they’re going to stop eventually, so I can stop. I love the job, but I don’t want to get to that point where I outstay my welcome. Like I said, I’m considered to be elderly now, so the fact that I’m doing this...we go back to absurd. If I get to a point where I don’t think I can do it well anymore—if people stop coming, or if they boo—then I’m gonna stop, ‘cause I love the job too much to not do it well.

MC: Any idea how you’d say goodbye?

Joel: I had an idea for a farewell tour. Everybody’s doing these farewell tours and they just keep going. I think the Who have done, like, 20 farewell tours, right?

So, my idea for a real farewell tour is the stage is set like a living room—there’s a TV, there’s a couch, there’s some chairs, there’s a refrigerator with some food in it. I come out, look in the fridge, take something out, make a sandwich, then I turn on the TV and I sit on the couch and watch TV. Now, the stage will be surrounded with bulletproof Plexiglas because eventually the crowd is going to start going, “Boo! Boo! Do something!” And after about 15 minutes I’ll pick up a mic and say, “Hey, I just said I was gonna be here. I didn’t say I was gonna do anything.”

And then we’ll know that they’ll never pay a nickel to see me again. THAT’s a farewell tour. So, if you ever see me just watching TV, you’ll know it’s over.

Contact Claire Mercuri, claire@clairemercuri.com

Sidebar with Sax Man Mark Rivera

During the nice weather months each year, you’ll find Billy Joel playing a selection of mostly baseball stadiums around the U.S. in addition to his monthly shows at New York’s Madison Square Garden. But this fall he’s taking fans back to a particularly special outdoors engagement—June 22-23, 1990 at the old Yankee Stadium in the Bronx, which was filmed and released later that year. An expanding edition of the film returning Oct. 5 and 9 for screenings at theaters around the world (BillyJoel.film for locations and tickets) and on Nov. 4 will be released in Blu-ray, CD and LP formats. These were landmark shows that paired the man who made the “New York State of Mind” with one of the Big Apple’s most iconic spots, a match made in musical heaven. As the release nears, multi-instrumentalist Mark Rivera—celebrating his 40th anniversary as a member of Joel’s Band—took us back to the Bronx to remember those special shows...

MC: It must’ve been a thrill for a New Yorker like yourself to perform at Yankee Stadium back in 1990.

Mark Rivera: Oh man, you have no idea. It was incredible. It was hallowed ground—it really was. I have these pictures of myself with a Jimi Hendrix T-shirt on, hugging the monument of Babe Ruth, back there with (Mickey) Mantle. And it was my second son Derio’s sixth birthday, on June 23rd, when Billy introduced me, “Playing center field, from Brooklyn, New York, Mark Rivera” and he added “It’s his son Derio’s sixth birthday!” It was wonderful, just wonderful.

MC: And the gig itself?

Rivera: It’s hard for me to put into words particular things that stood out. The whole thing was amazing. It’s joyous to see it—the players, the faces, the crowd. It’s Yankee Stadium, and now we’re the house band at Madison Square Garden. You know what I mean? It doesn’t stop.

MC: Playing stadiums is a challenge, not only technologically but also for performing. How do you do it successfully?

Rivera: I think the biggest challenge is your enthusiasm, your own, personal enthusiasm. I think Nureyev or somebody like that said that if you try to project out as far as you can go—in other words as far as the venue is—you’ll always lose. You can’t go out and try to reach everybody. But if you go inside and you’re there and you’re present in that moment, people will see it from the rafters. I’ve had people say to me, “I was up in the (section) 200, 300 seats. I saw you smiling.” I’m like, “Really?,” and I guess it’s true. Presence is everything.

MC: Interestingly, Billy is the only performer to play both Yankee and Shea Stadiums (July 16 and 18, 2008). Can you compare the two?

Rivera: It’s so different. First and foremost, it’s a completely different band and technologically speaking it was a completely different animal. We also had, what, 12 different people come up and join us, and you had (Paul) McCartney to put a cherry on top. But I’ll tell you, the hardest thing to do is carry a stadium alone, which Billy did at Yankee Stadium. It was just the band. There weren’t’ any guests—not to negate how great Shea was, because Shea was fanatics, and one of my favorites. But at Yankee Stadium, Billy stood alone with his band, and that to me was huge.

MC: You’re 40 years with Billy this year, a very long and happy tenure. Do you get a watch or a fruit basket or anything?

Rivera: I’m gonna have a mud wrap at the spa of my choice. (laughs) But y’know what? Forty years, and I hope he tells me that we still have another chapter ahead of me, and I believe we do. Someone said, “When are you going to retire,” and (Joel) said, “What the hell would I do?” This IS what we do—we play, we perform. Being on stage and performing, it’s oxygen for us, and without it we perish. I really believe that. It’s not ego, it’s just a sense of purpose, and believe me we have a sense of purpose in this band, and as musicians it’s very important to us. •