Acclaimed music historian Harvey Kubernik gives a special appreciation of Guy Webster, known for his iconic images of classic rock heroes like the Rolling Stones, the Doors, Carole King, and many more.

Guy Webster (September 14, 1939-February 5, 2019)

He Brought Us Closer To The Music

By Harvey Kubernik © 2019

Photography icon Guy Webster (September 14, 1939- February 5th, 2019) has passed. He had been suffering from diabetes and liver cancer.

An email from his office announced his physical departure from Ojai, California.

"Thousands of candles can be lit from a single candle, and the life of that candle will not be shortened. Happiness never decreases by being shared. Do not dwell in the past, do not dream of the future, concentrate the mind on the present moment. Even death is not to be feared by one who has lived wisely." Buddha

Guy Webster

Guy Webster established his reputation as a photographer capable not only of capturing the emotional nuance of the era, but also of helping to define it, with shots of hundreds of personalities before they were legends—including Simon & Garfunkel, Jack Nicholson, Dennis Hopper, Bob Dylan, Jane Fonda, Jim Morrison, Natalie Wood, Janis Joplin, Barbra Streisand, Raquel Welch, Cher, Jimi Hendrix, Brian Jones, Keith Richard, and Mick Jagger.

A slew of album covers Guy snapped in 1965 and ’66 of The Rolling Stones, Simon & Garfunkel, The Doors, Love, and The Byrds altered my life along with the sounds I investigated inside the cardboard.

Rolling Stones

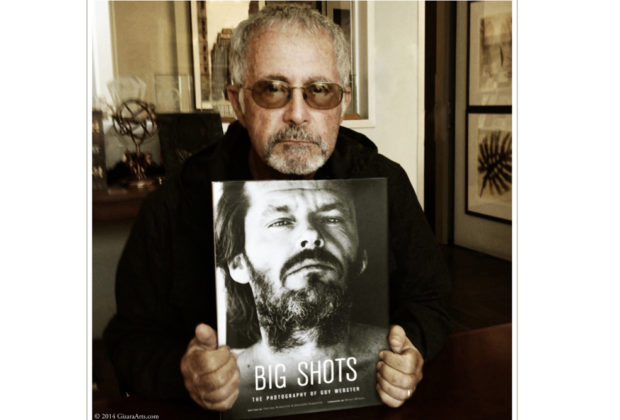

In October 2014, Insight Editions published the coffee table format Big Shots: Rock Legends and Hollywood Icons The Photography of Guy Webster by Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik Photographs by Guy Webster; Foreword by Brian Wilson.

I wrote the text and captions for Big Shots with my brother Kenneth, and along with Guy, we traced the enduring legacy of the time, providing a backdrop for his candid, behind-the-scenes stories about photographing some of the world’s most influential pop culture figures.

In April 2015, Big Shots won the Benjamin Franklin Award Gold Medal award in Art & Photography from the Independent Book Publishing Association. In May 2015, the book garnered the Independent Publisher Award Bronze Medal in the category of Photography.

In April 2017 I wrote and assembled 1967-A Complete Rock History Of The Summer of Love published by Sterling/Barnes and Noble. Guy Webster was very generous providing era photographs and studio portraits that grace the pages.

His belief and support in my literary expeditions are treasured.

Lou Adler: Guy...set the bar extremely high for ‘pop and rock’ photography and photographers...His photos were worth not ‘a,’ but thousands of words...His creativity...sensitivity and understanding of the subjects’ art and vision helped start and endure many careers…Guy Webster is iconic...”

Andrew Loog Oldham: Coming to America with the Rolling Stones gave us an opportunity to meet new people in the field of music, graphic arts and photography.

“Lou Adler suggested we meet photographer Guy Webster in 1965. We were recording at RCA Studios on Sunset Blvd. I invited Guy to the session. He took some photos. Guy arranged a photo shoot outdoors in the hills of Hollywood.

"We had a day off and did good work. That's all you can ask for. Guy delivered.

"The results are on the front covers on the albums Big Hits (High Tide and Green Grass), The UK Aftermath and Flowers.”

Chris Hillman: We did the Byrds’ Turn! Turn! Turn! cover at Guy’s studio at his parents’ house in Beverly Hills. Terry Melcher our producer at Columbia knew Guy, and they had done some work previously. That’s where I first really met Guy Webster.

“There we are. (David) Crosby is in his cape. (Roger) McGuinn has got the glasses on, and the ever so fashionable hounds tooth sport coat. And then Gene (Clarke) and Michael (Clark) and I have our perfectly coiffed Beatle hair. It’s all in blue. Guy’s father was a very famous songwriter. I knew that.

“That LP cover and the music on Turn! Turn! Turn! was the breakthrough. The breakthrough record was ‘Mr. Tambourine Man,’ but the breakthrough album was that. ‘Turn! ‘Turn! Turn!’ is the most recognizable Byrds’ song way over ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ with all due respect. That’s the Byrds’ song people always remember. It’s the LP cover I autographed the most.

“I know the time period when the only delivery method was an album with LP cover art. The album cover meant a lot then. Jim Marshall was in San Francisco as was Guy Webster in Southern California shooting, and then (Henry) Diltz came along just a bit after and was the next generation. Guy was very good at his job. And, of course, my time with him then I was so shy. I barely said four words within an hour in the early days of the Byrds. He did a great job.

“Later Guy re-enters my life doing the cover of the Byrds’ Notorious Byrds Brothers. We literally rode back from Topanga Canyon, and Guy found a location and subsequently placed equipment on a horse as part of the shot. And the question was ‘why did I have my shirt off?’ And then, of course, for many years, ‘Oh the horse was David Crosby.’ No. It was just a great shot.”

Henry Diltz: Guy Webster was a famous music photographer, about a year or two before me, like 1964-’65. He photographed The Mamas & The Papas a lot and many L.A. groups, mostly for Dunhill Records. He came from a family that was fairly well-to-do because his father was this famous songwriter and wrote some very famous songs that are very much standard songs in our lives.

“I know he likes motorcycles. He lived out in Malibu and a very nice chap. I met him a few times. He was very prolific and he photographed our group The MFQ for Dunhill Records. There's a shot of me. I kind of have mutton-chops. ‘Fast’ Eddie Hoh was in the group. We all looked pretty ragged. He took us up to Mulholland.

“Guy did some fantastic work. He aided the forward movement of everything... music. He did some great Mamas and Papas album covers. Guy was kind of a forerunner of music photographers really, sort of like Jim Marshall in San Francisco.”

Michelle Phillips: We did a lot of stuff with Guy. We worked so many times together. He was there when we auditioned for Lou [Adler] and our album covers. I modeled in New York before the Mamas and the Papas even started. I had a relationship with the camera before I met Guy.

“Guy and his camera were always around. He came to us from Lou Adler. They had done a Barry McGuire album cover.

“I remember our first photo shoot with Guy. He just came over to the house in West Hollywood. On Flores Street right near Fountain Avenue. We rented a house. There’s a photo of us having a picnic in the back yard. Guy came over to shoot us and we were just in the same clothes, the only clothes that we had, And it’s funny, but you know when I look at that first album cover that’s exactly what kids are wearing today. Well you know what, we were wearing jeans, and chords and everything that you would normally wear. We never dressed up. Until we got very rich. (laughs).

“Guy was always there. He was kind of like a fly on the wall but much more. We never thought about it. He took pictures and would talk to Lou and John about music publishing and travel with us.

“And Guy never even thought about exploiting us or using me in shots. I wasn’t Jill St. John, you know what I mean? We were a completely different breed. And also, there was always John Phillips standing over watching what was happening. And he really would never have allowed me to wear high heels on stage. He carefully cultivated our image. He said, ‘You can not wear high heels. You can not wear dresses.’ I mean, Cass could wear a dress, but I could not wear a dress. We weren’t the Supremes. John did not want me exploited as kind of a sex symbol. And when you see us on film it’s really funny. I’m wearing long sleeve shorts buttoned up to my neck.

“The photos of the Mamas and the Papas work in black and white and in color. First of all, we were a very unusual looking group. And it didn’t have to be. Remember the name of the first album: If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears. If you believe your eyes you’re gonna look at that picture. And it doesn’t matter if it’s in color. It’s fine in black and white. Because everyone is looking at this very overweight beautiful woman who sang like a bird, and then there was this tall thin blonde with long hair, and this beautiful Denny and this tall guy with a mink hat on. It was something that you just didn’t look away from. You were gonna look at that picture and try to dissect who these people were. We were always very animated, too. So it wasn’t a static pose.

“The pictures of the band all the way through show that we were going through so much. We were always kind of living our drama. The drama can be seen in many of those photographs.

“Guy was very laid back. He never made himself ‘The photographer.’ Guy was always just your friend. He had a camera. He was taking pictures and we were all laughing together. We were all prancing around the house trying to find, you know, the perfect shot. He just let us do our schtick. And he followed us around and he liked it. Guy kind of captured us being ourselves. And I don’t know if there are too many photographers that you feel that cozy with. And Guy was one of those people. And he was a very good photographer. It’s not like it was just somebody with a camera. He really got some fabulous shots. And I don’t think there was ever a wardrobe selection. (laughs). I’ll tell you, I didn’t have a bunch of clothes out on my bed deciding what I was gonna wear.

“I know on a pool shot when we jumped in we were all fully clothed. And that was the kind of thing that he loved. He loved our spontaneity. We didn’t plan that shot. We just all jumped in the pool. (laughs).”

Tom Gundelfinger O’Neal: I was basically a Fine Arts major in school. I was a painter and did photography because it was convenient and I had learned design and composition. But I still thought of myself as a painter.

“I loved Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol. William de Koenig and Rauschenberg. Franz Klein. I realized I didn’t have a direction when I walked into a record store in Carmel California and picked up a Mamas and Papas album with a Guy Webster photo in a swimming pool. It was an epiphany.

“And this photo was on a canvas and it was animated. It was alive. They jumped off the cover. And the music was happening.

“I saw the Guy Webster black and white photo of the group, also in Playboy magazine of them. I was drawn to Guy’s composition and the way he placed them. ‘This is it! This is what I want to do!’ I want to arrange people like this. He had this visual flow. Very influential and turned me on.”

Ray Manzarek: Click, snap, shutter slams against itself. Click again, whirr, snap

shutter slam. Guy on the job. Working, cajoling us, massaging our

fragile egos. "Get closer together. It's alright to touch each

other. Don't be so stiff." Jim says, "Hey man, it's our first photo

session. We're not the happy go lucky Beatles." Guy says, "Well, try

to smile more. Could you try that? Please." Robby says, "We're a

serious group, Guy. As a matter of fact, we're the most serious group

there is!" We all laugh. Guy doesn't snap. What's he waiting for?

We're being light and happy. Hell we're shooting an album cover and

it's our first album and it includes Light My Fire and The End and

Break on Through. It's great and sounds great and we look great. How

can we not be happy? And he's not shooting. "Shoot now, man," I

say. And he does. Click, snap, shutter slam, whirr. Lights pop,

blind us. We stop laughing and it's serious time again. Strobes,

umbrella lights. Flash, pop, slam the eyeballs. We scowl, grimace.

"Ouch," says John. "Those lights are too damn bright, Guy." Guy

keeps shooting. And damn if he doesn't get a great album cover. Big

Jim head. Ray, Robby, John as Jim's eyeballs. And a superimposition

line up on the back cover. One of the golden screws on my glasses is

right at Jim's eye and looks like a tear drop. The poet, crying. No

more need be done. Session over.”

David Leaf: It’s one thing to take great pictures. It’s quite another to capture history. Guy did both, magnificently, at a time when music in L.A. was often at the center of the pop culture universe. Treasure the visual legacy he left us. His eyes saw artistry. His soul felt the magic. His photographs allow us to share the moments forever.”

Heather Harris: Guy Webster photographed the top echelon of actors and musicians for the last half century, his notoriety for most beginning with his bathroom portrait on the cover of the debut LP of million-selling The Mamas and The Papas although he was a full time pro far earlier. He was known for bringing a studio quality to candids and vice versa, but I associate his style with that of summoning dreamlike memories of stars rather than playing up their most stereotypical qualities, which was infinitely better.”

Kenneth Kubernik: Guy Webster could make a photograph sing, his ‘eye’ endowed with an orchestral flourish. He had an unerring sense for being in the right place at the right time; his creative life a kind of magical mystical tour through the kaleidoscopic '60s, capturing its tactile effervescence in a series of indelible images. He was a suave, rudely handsome magnet for women who coveted his artful tenderness, a righteous dude among the pride of movers and shakers who valued his cool counsel. It was a great privilege to work with him on his pictorial memoir, Big Shots. He photographed icons and, by virtue of his talent and decency, became one himself.”

Our memorable Big Shots collaboration with Guy features more than 300 photographs, and a foreword by Brian Wilson, with contributions from Michelle Phillips, Peggy Lipton, Chris Hillman, Andrew Loog Oldham, and Ray Manzarek, and many others, Big Shots is an evocative retrospective of a transformative and influential time and place.

Guy Webster is one of the early innovators of rock-and-roll photography. He spanned the worlds of music, film, and politics in a remarkable fifty-five year career. While shooting album covers and billboards for numerous groups—including the Rolling Stones, the Mamas and the Papas, the Beach Boys, the Byrds, Love, the Doors, Simon & Garfunkel, the Hollies, Spirit, Paul Revere & the Raiders, Nancy Sinatra, the Turtles, Procol Harum, Laura Nyro, Lee Michaels, and Taj Mahal.

He also photographed such film legends as Rita Hayworth, Dean Martin, Gena Rowlands, Joan Collins, and Natalie Wood.

As the primary celebrity photographer for hundreds of magazines worldwide, Webster has captured a vast range of talent and luminaries, from Igor Stravinsky, Truman Capote, to Zubin Mehta and Candice Bergen. His presidential subjects include Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton.

A native Angelino and raised in Beverly Hills, Guy Webster and his brother Roger are the sons of a three-time Oscar-winning songwriter, Paul Francis Webster and wife Gloria.

After graduating from Beverly Hills High school, Webster went to the Art Center College of Design. His work became omnipresent in magazines and newspapers, album covers and music and fashion ads from1964 to 1971.

Webster’s first album cover, Three Window Coupe by The Rip Chords (of “Hey Little Cobra” fame), produced by Terry Melcher, consequently put him on a path that proved he was never content to simply capture the moment, his camera burrowed into the essential character of his subjects: the brooding edge of the young Rolling Stones, the insouciant charm of The Mamas and the Papas.

In 1966-67 Guy traveled with The Mamas and the Papas and The Beach Boys, while also photographing Brian Wilson during his creation of SMiLE. Webster shot the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival, and his work appeared in the now infamous program.

Guy lensed L.P. covers from 1964-1971 that informed our still ongoing musical history and impacted our lives.

Carole King

Simon and Garfunkel on a dirt road for the cover of their 1966 album Sounds of Silence; The Mamas and the Papas’ initial LP, If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears; The Rolling Stones’ Big Hits (High Tide and Green Grass). Webster provided photos for the Stones’ Flowers collection, as well as shooting the self-titled L.P. front covers of the debut albums from the Doors and Spirit in addition to Carole King’s Writer, Van Dyke Parks’ Song Cycle, and Recital from Lee Michaels. Webster also snapped the photo of the Turtles’ Happy Together” LP front cover. Guy also provided the back cover photography and hand-made collage on Love’s Da Capo.

Webster was also hired by record labels, including Elektra, Warner Brothers, Columbia, and A&M Records, where he was co-art director.

During his music career, Webster provided the film stills for Goin’ South, The Wind and the Lion, and They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, also snapping John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands on their movie sets.

Webster left America in 1971, uncomfortable with then President Richard Nixon and the ongoing war in Vietnam. He lived half of the decade in Spain and Italy and traveled to Morocco in 1974 or ’75, also visiting France, Austria and Germany over a six month period. Webster earned a Masters Degree in Fine Art from the University of Florence.

After he relocated back to California, Webster moved to Ojai in 1980 with his second wife, Leone, a former model and actress. The Websters have five adult children, three from a previous marriage, and two grandkids.

Guy administered his late father’s music publishing company, around his passion for Italian motorcycles.

Webster taught photography at the Oak Grove School in Ojai, Calif and involved with the Krishnamurti Foundation of America. He was enthusiastic about his motorcycle collection and museum in Ojai.

In 2011 I interviewed Guy Webster for Treats! magazine. A portion of our conversation was published in Treats! and then subsequently in my anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood.

Harvey Kubernik Interviews Guy Webster

Q: How did you enter the world of photography?

A: I’m a Quaker, but I was a conscientious objector and went into the army for six months at Fort Ord in 1961. And they didn’t know what to do with me. They thought I was gay ’cause I didn’t want to kill anyone. No killing or shooting, nothing. “I’ll go in and be whatever you want in the office.” I had attended Whittier College, a Quaker school. “You want to be a clerk typist?” “Do you have anything else?” “What about decorating Christmas trees on the base.” “Perfect.” I decorated hundreds of Christmas trees throughout the barracks, all over. Then the season ended and I had three months left. “What do you want to do?” “What have you got?” “How ’bout photography?” “Yes, I know everything about photography.”

I lied. I knew nothing and had never taken a photograph. I was to teach recruits how to use cameras. I immediately checked out three books on photography at the library and I read how to develop film on paper. ’Cause in twenty-four hours I was gonna teach photography to the recruits in the dark room. I mixed the chemicals properly, the proper temperature, they came in. “Put it in here for two minutes…” Then I washed it.

I had connections in the army. People took care of me. I lived off the base in a private home. I had every weekend off. There was a famous producer who knew I was home every weekend. “Guy, you’re in the army. Take my Nikon and shoot while you’re doing this. You’ve got three months left.”

So I took a Nikon and shot some pictures. Even though I could use more than one roll, I had one roll in it and shot 36 pictures. Each one different. Waiting for hours for the light to be right. All black and white and I processed it and printed it in the dark room. No one was in there while I was working. I was supposed to go to Yale, and so I got out. When I said “No, thank you,” my parents said, “That’s it. You’re done with us.” I was now out of the army, I had no money, I wanted to go to the Art Center School of Design and I didn’t have a camera. Then this Mafia princess, who was a girlfriend, said, “I’ll get you a camera. I’ll talk to my dad.” So she went to her father, and the guy said, “Sure, pick out any cameras he wants from the garage. Just take the whole thing.” She came over and presented me with a case of Pentax cameras and lenses. Now I could go to school. And I went to Art Center. They wanted me desperately. They would not let me go anywhere else. And that’s what happened. And within six months I was making money. And within a year I bought a house. And, within two years after I finished Art Center, I was making as much as my father. Crazy.

Q: What did you learn from the Art Center College of Design that helped your portfolio and informed your subsequent photography work? Just about all your music images are portrait sessions and not live photos, except for a few, like performance pictures of Barbra Streisand and Jimi Hendrix. You have always used studio and environment settings for photos of music subjects.

A: I had studied art my whole life and I actually have a Masters Degree in Fine Art from the University of Florence, so the renaissance, particularly, was very influential for me, and I shot like Caravaggio whenever I had a chance. I’m influenced by the Dutch master Johannes Vermeer -- remember the film, The Girl with The Pearl Earring? -- and also influenced by the moody and dark self-portraits of the painter Rembrandt. It was natural when I started shooting.

I never meant to be a commercial photographer. I was going to be a fine art photographer. And (record producer) Terry Melcher said, “Hey, let’s do an album cover for The Rip Chords.” And I was still in school. It was for their Three Window Coupe album, with their song “Hey Little Cobra.” Terry and I were great friends. The Rip Chords cover is in the Ventura exhibit. Terry actually got me started thinking, “I can shoot some album covers and make some money.”

Q: In December 1965, you took photos of Bob Dylan at his Hollywood press conference, held in the Columbia Records Press Room and arranged by Billy James from the label.

A: You don't work with Bob. There's not that connection there. You just do your thing.

Q: You were not a stranger to the world of music and show business. Your father, the lyricist and songwriter Paul Francis Webster, earned three Academy Awards for Best Original Song. “Secret Love,” “Love is a Many-Splendored Thing,” with Sammy Fain, and “The Shadow of Your Smile” with Johnny Mandel. He also penned the standard “I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good).”

His first hit lyric and music from John Jacob Loeb was in 1932 for “Masquerade,” performed by Paul Whiteman. In 1941 he collaborated with Duke Ellington. And in 1967 he was asked to write the lyrics to Mandel’s music for the “Spider Man” theme of the television cartoon series.

A: Yes, my house was filled with unbelievable talent as a child. Ella Fitzgerald, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Hoagy Carmichael. The most important to me was Duke Ellington. I met him when I was 5 years old and we went out to lunch many times with my dad when he was doing the stage show Jump for Joy. Duke and other musicians contributed to the original score.

Q: You never really succumbed to anything near a crazed rock ’n’ roll lifestyle that you were photographing, let alone super impressed by the stars you knew and documented.

A: I loved the musicians, actors, and directors. I liked their music and movies and I made some friends, but I didn’t get caught up in it. I grew up in a world of celebrity. A celebrity I was shooting was no different to me than the guy next door. And I think that’s why all these stars were comfortable with me.

Let me give you an example. From a very early age I was in a couple of films. My father was very proud of me and would take me to the movie studio where he was writing songs for films. And I watched these songs being created and the people singing them. And his first big international hits. He wrote this song, “Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing.” I think it’s beautiful. It is schmaltzy. Nobody would record it. Nat King Cole, Tony Martin. They offered people Cadillac cars under the table to record it. Until the Four Aces, which was a beginning group just getting started, said they would do it. And it went on to be the biggest song for the decade.

That’s what I watched. I learned how hard it is to get a number one single and to promote it. And my dad was tireless about that. When he wasn’t writing for hire he still wrote. And I was working with him on publishing. ’Cause I’m left brain and right brain and ambidextrous.

I ran the music publishing company while I was doing photography, and my brother and I own it today. Now, I’m responsible for that, because the company that was producing the Spider Man cartoon came to me and said, “Would your dad write us a song?” He’d written two or three famous television themes, like Maverick. I said, “I don’t know if he would do that. How much are you offering?” We worked out a deal. I then went to him and said, “You’re writing this song.” He literally wrote it in ten minutes. And it’s been one of the biggest copyrights we’ve ever owned, because of the movies and television. Aerosmith did “Spider Man.”

Q: Did your dad look down at rock ‘n’ roll when it first started getting on the radio and you were involved in the visual aspect of photographing different music in the mid-’60s?

A: No. He wasn’t like that. He was very shy, like an English professor. He was brilliant and knew every word in the dictionary, all the different spellings, all the different meanings. He wasn’t threatened by rock ’n’ roll in the mid and late ’50s, because he was making big hits during the ’50s and the ’60s. You know, “Somewhere My Love,” which combines his lyrics with the melody of “Lara's Theme” from the film Doctor Zhivago. He was doing OK. But he didn’t like anyone except Bob Dylan. And I said, “Wait a minute, there’s a lot of guys out there!”

I told him I was going to photograph Simon & Garfunkel for an LP cover and I wanted him to meet them. I brought Simon & Garfunkel by, and my father and Paul Simon hit it off because he learned Simon was a Dickensian scholar. So was my dad. He had a Dickens collection. Then Paul Simon said, “Hey, you want to hear our new song?” And he pulled out his guitar in the living room, in Beverly Hills, and my dad was sitting there, who is not a rock and roller, and he listened to “Sounds of Silence” for the first time. “Oh my God, you guys. What a brilliant song.” I took Paul and Art up to a dirt road in Franklin Canyon and shot the cover of Sounds of Silence for Columbia Records. The name Garfunkel got me. I never forgot it. I heard “Sounds of Silence” five or six times before I shot the cover. And I wanted that thing where they’re walking down the road, a little English with the scarves behind them, with Art’s hair. And he and I became friends. Simon was more east coast. Art used to come out and stay at my house once in a while. He was a very cool guy.

And my dad started to realize that there was more to rock ’n’ roll than just the hard beat that most people associated with it. I later played him Procol Harum’s “Shine on Brightly,” and he understood Keith Reid’s lyrics. Not gonna give you names but mutual friends of ours did not like rock ’n’ roll.

Q: How did your rock ’n’ roll photography career begin?

A: I have to go back a ways. In 1964, maybe ’65, I was playing basketball with Terry Melcher and Lou Adler. I was in art school and had an incredible portfolio of photography. It was the one thing I really invested in. I had no money, even though my parents were well off, I was completely cut off because I went into photography rather than to Yale. Luckily I went to a great college first.

I was supposed to go to Yale to study, I had a seat on the stock exchange with my uncle. When I turned that down to become a photographer, they stopped any help. And I was about 21, just out of the army. I was playing basketball with Lou and Terry. And Lou said to me, “I hear you are a great photographer. I’d love to see your work.” “Well, my Volkswagen is right outside. I’ll show it to you.” I opened up these giant 16x20 prints and he went, “Oh my God. These are great. I want you to come with me. I’m starting a record company called Dunhill. We have no money, basically, and I have one singer, Barry McGuire. And I want you to shoot the cover and design and do all that.” And together we started our careers.

Lou was already in the business, producing Jan & Dean and had worked for Aldon Music. All of a sudden the Barry McGuire record, “Eve of Destruction,” hit number one and I never stopped working from that day on and, of course, neither did Lou.

Q: In your show and on your website you have a photograph from your 1965 session with The Rolling Stones, as you shot photos of the original band for their Big Hits (High Tide and Green Grass) album. A monumental photo session conducted in Southern California when the band was recording at RCA studios on Sunset Blvd. You also have the cover jacket of Aftermath.

A: That session wasn’t easy. But Lou Adler introduced me to Andrew Loog Oldham, the Rolling Stones’ manager, record producer and publicist in 1965. And we got along quite well. Andrew said, “My boys are coming. Do you want to shoot them?” I said it would be an honor. Because it’s not that I didn’t love the Beatles, but the Stones spoke to me viscerally. And I’m a blues guy. I grew up with the blues. I had Big Joe Turner in my house when I was a child. So I knew the blues. The Stones were originally a blues band and that’s what I loved about them. I was invited to the Stones’ RCA recording sessions. It’s not lost on me that Sam Cooke and blues and jazz musicians cut in that room. I grew up there. I watched the Stones record.

First of all, I thought they were beautiful to look at. Visually beautiful. That’s what happened in the ’60s. When the long hair started coming in, men who were average looking started to look beautiful. And I’m talking about it as an artist. I’m looking at them. And it was so much fun to photograph them because of that. And they inspired me. I loved the Stones and couldn’t believe their sound.

And Andrew said to me, “I don’t want to pay you, Guy, because it’s such an honor to shoot the Stones.” This is in the beginning. “And I want you to waive your fee.” And I said, “Andrew. Come on, you know I’m just talking about five hundred dollars. You know, that’s all. It’s not five thousand here. I gotta ask for that and I insist on that. Because I’m doing the back cover, the inside graphics, all that stuff. Come on.” So Andrew paid me five hundred dollars and took the pictures. And I had no idea he would be using them for covers in Europe, for picture sleeve singles. When I started traveling to Europe to shoot bands, I would see my work in England, France and Spain. “How did that happen?” Then I started to realize that I would need to be watching the deals that I made with people. Not that Andrew did anything illegal. It was the impulsive nature of the business. Get the picture out. “We need a photo for that.”

Q: And, by doing it that way with the Stones, you owned the images in perpetuity.

A: And I knew I was going to be successful. All my friends said, “With your talent, you’re going to be successful.” So I wasn’t thinking about money. And if Andrew had offered me a thousand to own them I don’t think I would have done it.

As for the session, I took the Stones up to a girlfriend’s house. I knew the land and the property. I didn’t even ask. I didn’t have to. And I took the band out there with a limousine up a dirt road and we shot those pictures in town. Using photos was how you spread the word back then. I posed the band. I collaborated with them. I bonded with Brian Jones. He was a blues man. We both had that background and we had an immediate friendship because of that. The other guys were blues guys, but they weren’t committed like Brian to the blues scene. You know the story. Brian wanted it to stay a blues band forever. I have a memory of that shoot. Everybody was stoned but me. And I had to kind of push them around physically to get them into place. Because they were laid back and stoned a little bit.

Later, I went with the Stones to the Beverly Wilshire Hotel in the limousine and it was bedlam. You couldn’t see. The car went completely black from faces on the windows. There was not one space of light as all the girls covered the glass windows.

Q: What was it about the Rolling Stones that appealed to you visually. Onstage the Beatles dressed the same way in suits.

A: Each Stone dressed individually. And a lot of the bands, even unattractive bands, like Canned Heat, I loved them. Because they were all blues guys. And I didn’t care what Al Wilson or Bob Hite looked like.

Q: Later Mick Jagger came over to your parents’ house where you had a remote-controlled sailboat.

A: I was into model boots that were radio controlled. We were in the studio and there was a potato bug and we sailed it around the pool. Mick and I did that together and watched the boat go around the pool. Because you have to understand, we were just getting into adulthood and we still were kids. And they were still in some ways very green and just getting into the sex thing.

Q: Why did the British Invasion have such an impact on the U.S. in early 1964, ’65 and ’67, that you witnessed up close? I know TV exposures on “The Ed Sullivan Show” helped, and eventually AM radio spread the music.

A: I think because it was wild. We had our rockabilly guys, they were a little wilder, but these were guys whom these girls could date. These were hot English guys with an attitude, and they were sexual and nasty. That really related to everybody. The looks they would give were fantastic.

In 1966 I shot the band again, and in 1967 I was the staff photographer for the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival. Brian Jones was with Nico. I would later do her album cover for The Marble Index. We actually got to know each other at the Monterey festival pretty well. I hung out with Nico and Brian.

Q: You had a Grammy nomination for the cover of The Byrds’ Turn! Turn! Turn! album. Then there was your embedded collaboration with The Mamas and the Papas. You photographed them for the whole ride.

A: That started with Lou Adler, who discovered and produced them.

Lou called me and said, “Barry McGuire is sending over this group and he wants us to listen to them.” So I went into Lou’s office at Dunhill Records, and in came the four Mamas and Papas and they were visually very interesting. Michelle Phillips. Gorgeous girl. Everybody wanted to fuck Michelle. She was it. Cass was wonderful. I knew Cass really well and we were close friends. And Denny was great. What a voice. So Lou and I were the only two people in the office and they started singing “California Dreaming,” and Lou and I looked at each other and locked eyes. Oh my God! That is it. We just saw money signs. I went to every recording session Lou did with (engineer) Bones Howe. I shot the front cover of their album, If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears, in the bathroom of a house that was rented at the mouth of Franklin Canyon.

In 1966, we were sitting around and I think it was Cass who pulled out some grass from tin foil and lit it with all the windows and doors closed. And we were supposed to shoot our album cover. And we were all really stoned. I couldn’t set up my tripod. So I said, “We gotta shoot something.” And in that apartment was that 1920s and 1930s bathroom with all the tile. I put them in the bathtub and I set up my tripod and my big two-and-a-quarter camera and shot that picture. And in that picture for the album cover, shot with my wide angle lens, was the toilet. I had no idea when we produced this and neither did Lou. You can’t put a toilet on the cover of anything and sell it at Sears or one of those chain stores. They will not allow it. So Lou came up with a great idea, to put a little sticker on the shrink-wrap that said, “Including ‘California Dreaming’.” And that covered the toilet. Kid opens it up and there it is.

It became one of the most controversial album covers of its day. Which pleased us to no end I became best friends with The Mamas and the Papas. John Phillips was from another world. You see, John Phillips became a hippie, but he wasn’t. When I first met him, he was not a hippie. He was a bright folk singer who could write beautiful songs. John Phillips and I could be friends. The group was educated. John and I could talk philosophy, religion, politics. I think John helped Lou and Lou brought John into the modern world of music publishing.

I was also with Lou and the group at the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival as the official photographer for the festival and the program. The police were so nice there. I took the photo of the cop with the flower.

When Esquire Magazine did an article, “The 100 Heavyweights of Rock ’n’ Roll,” I was one of them. I was treated by the musicians with great respect and I treated them with great respect. I used to say to the bands I shot, “Let’s have fun, because you’ll probably never want to pose together again. Look I’m telling you. You’re going to get into arguments over money. And next year you’re not gonna all be here.” And I did it with a sense of humor. And the truth was the bands all broke up and new people came in.

Q: Your iconic cover photo on the debut Doors album that primarily portrayed Jim Morrison. An LP jacket that brought so many eyes and ears into the brave new mono and stereo world the Doors captured on analog tape. How did that event happen?

A: Jac Holzman, who owned Elektra Records, called me on the telephone and said, “I have a group I want you to photograph.” “OK.” “Well, they are out at the Whisky a Go Go.” “Alright. I’ll listen to them.” I didn’t know who they were. I saw them and I liked them, but I was listening to a lot of stuff back in those days. So we had them scheduled to come into my studio, which at that time was located at my parent’s house, in the back. Because even though I was shooting all outdoors stuff at the time, when I wanted to shoot studio, I had a small studio there. And I wanted to do them in the studio so I could get some very intimate pictures of them. And in walked Jim Morrison. And he said, “Guy.” “How do you know me?” “Guy, we went to school together.” “Oh my God. Jim!

“We were at UCLA together in the philosophy department and we used to read Nietzsche together.” And I went, “Shit. I didn’t know you were a singer or a poet.” I was shocked. And the other guys, and this is a terrible thing, and I know they were angry at me, because I put Jim’s face forward and I designed the cover and put the other three guys as his eyes and part of his brain. But I made Jim the star on purpose ’cause I knew it could sell the album. Jac liked it and put that on the cover. He always let me do what I wanted for the cover.

Here’s the deal on Jim taking his shirt off for the session. Once we realized that we were in school together and that I was already famous with my album covers, I said, “Look Jim. You’re wearing this shirt and it’s embarrassing because it has ribbons on it. I know it’s a hippie shirt but you can buy it in Venice Beach and you can buy it anywhere.” And it would have dated him. “I’m gonna take your shirt off. You’ll be alright. Trust me. And I’m gonna make you look like Jesus Christ.” And that’s what it was. And they went with it.

I loved the band live. Oh my God. I later knew that Jim was singing and he had been in class with me. But I was listening to Ray Manzarek’s organ. That was brilliant and that’s what impressed me more than anything. Man, this guy could smoke that keyboard and he was a white guy with little glasses. So I was really impressed.

Q: What about the montage or the superimposition aspect of that first Doors front cover? That was a new thing you were doing.

A: Yes, it was. Because I grew up with jazz and blues and all the album covers were just awful. They were against a yellow background, everybody in suits and similar poses, corny. Except for the work of photographer William Claxton, whom I was friends with, and he shot some great pictures and covers. Good guy and a good artist.

I wanted to do the same with rock ’n’ roll. What I wanted was, let’s get down to it. Here are these guys, they are singing about love, peace, and sex, and I wanted something to make them look sexy and I didn’t want them in a studio. I wanted them outdoors in nature, part of our life in the ’60s, Love-Ins, things like that. All natural. And I started putting the musicians and artists outdoors.

Q: You subsequently were around the Doors for a photo session in Westwood at the Veterans’ Cemetery next to UCLA in 1968, when the band did their video for “The Unknown Soldier” from the album, Waiting for the Sun.

A: Right. It was raining and very hard to take pictures without getting ugly buildings in the background. The one image on my website has Jim on the side. I was worried about putting it out there because it was too macabre so I didn’t push that photo. I loved the Vietnam commentary being done in front of me. Anything that was political. Morrison had a sense of fashion. He understood. He was super educated, even though he educated himself, going to UCLA at that time in the early ’60s and he came from a junior college.

Q: You also had an encounter with Jim in 1971.

A: I hadn’t seen him in a year before that. I was taking pictures of Natalie Wood. She was like a friend of ours, because my first wife and I were very close to Natalie and her husband, Richard Gregson. And I was friends with her. And she said, “Will you do some pictures for me.” “Absolutely.” So we went up to Malibu, to Serra Retreat, and we were shooting there. Not too many cars and she wouldn’t be bothered.

And this limousine pulled up and the window came down. And this burly 250 pound man with a full beard and hair said, “Guy.” “Who is it?” “Jim.” “Jim Morrison?” I didn’t recognize him. He asked, “What are you doing?” “Well, I’m just finishing up some work and then I’m moving to Spain and I’ll be there for quite a while.” And he said he was moving to France in the next week.” And I said, “Well, shit, we gotta get in touch.” And that was the last time I saw him…I moved to Spain and he moved to France and he died a couple of months later.

Q: You took photos of Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys, including some 1967 SMiLE period shots.

A: I love Brian. Child-like innocence, and he was playful. And I believe in that. One of the things about studying Buddhism all my life is getting that playful side, exposing it and don’t be afraid of it and let it out. Everything Brian did I loved. Even the silly songs like “Surfer Girl” I thought were brilliant.

“I saw Brian take pop music into a new direction. I feel it an honor that I was at the recording session for the vocals of “Good Vibrations.” Oh my God. I had chills up and down my arms and back the whole time. I had never seen anything like it and to be in that recording session and to see them practice in the halls getting their harmonies. Holy shit. That was a real treat. It’s one of the highlights of my musical life.

And Capitol Records a couple of years ago released the SMiLE box set with the original 1966 and ’67 sessions for that album. I took photos and involved in the new book and package. And Van Dyke Parks is the lyricist with Brian on SMiLE. And he’s brilliant. I did the cover of his Song Cycle album.

Q: I really dig the photos you took of Captain Beefheart.

A: I would have to say my favorite guy to work with. Because he was free thinking and not afraid to take chances. Not a corporate guy who was going to get the most money out of whatever it was. He was an artist. Derek Taylor sent him to me. Don (Van Vilet) came into my studio with the guys. ‘I haven’t heard your music. I’m sorry. I know you did Trout Masked Replica. Don didn’t have it with him but he said, ‘I want this album to be abba zabba.’ ‘Interesting. In my mind I thought I’m going to use abba zabba for the album cover. Black and yellow checkered album cover. It has become one of my most famous album covers. It was viewed in the movie High Fidelity. It’s the one album they will not sell. I was really proud of that.

The first thing I thought of in working with Captain and the band was that I would shoot them with a fish eye lens. Ordinarily I would not do that. No gimmicks. But for these guys let’s do the first shooting with a fish eye. Because it’s psychedelic in a way and you guys are so strange. And I do that. And I design the abba zabba around it. Tom Wilkes did some work on it. And they put it out. On the second album they come to my studio at A&M, the former Charlie Chaplin studio, and I’ve got the studio in the back. They come over. Don is dressed in a suit and tie, looking very sharp. And he tells me he wants this album cover, Strictly Personal. ‘OK.’ I shoot a head shot of him. A popular collectable. Even if they don’t know his music. So then he says I want you to shoot us straight where my face is shown and we’ll make postage size stamps out of that. Or I also want you to shoot us in costume. ‘Costumes?” “Yes. We call ourselves the 25th Century Quakers.’ We come out and play the blues and go off stage staying in masks and people think they are getting two groups. We them come out and do our music.’ I had never heard of that. It was so brilliant. I love this guy. He was a conceptual artist. I ended up playing their music. We really connected. We related to each other and he trusted me. I did another session as well.

Q: Over the years, you also photographed the model, actress and now author, Peggy Lipton, known for the Mod Squad television series.

A: I knew her over the years from her family, her parents, and brother, Robert Lipton. And we all were at the Daisy. Peggy was with a friend of mine and she was going with a guy and they would come over to my house. She went with Lou Adler and did an album. And I shot a lot of pictures of her. Not just for her album cover but pictures for magazines. She worked so well on camera. Peggy is a beautiful girl. Like on Mod Squad. One beautiful girl, with two guys on either side she starts to look really good. And she was great. She photographed good in black and white and color.

Q: Then there was Nico.

A: At the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967 I saw Brian Jones and Nico and hung out with them. He remembered me from two years earlier when I did photos with him. I first saw Nico in a movie La Dolce Vita.

This gorgeous German beauty. When I meet her at Monterey she was so beautiful. She was blonde. She later came into my studio and we had an immediate connection. It was for Marble Index. She was blonde and I darkened her hair. At this time I had a big studio at my four acre farm in Beverly Hills. I had goats and horses. She came to visit and do this album cover. ‘Guy good to see you.’ She had a nasty voice. ‘You’re are so beauty. This is going to be the easiest photograph.’ She didn’t have much time. Maybe two or three hours. So I take her into my studio and I light her. I noticed her amphetamine lips and I knew I had to get that into the picture. She had been a model. I asked her not to model. Just look right in the camera. I did it on a black background with a light behind her head so that I could bring her forward. It was Andy Warhol’s favorite picture. He had a copy in his studio. I did the back cover, full length with her boots. A unique body.

After the album comes out I don’t see her. She went back to New York and Europe. I later had a farm in Spain. In Menorca.

End of 1971, I’m sitting at the American bar. The main square of my home. By myself. I’m lonely but not sad. The fog has set in from the ocean. It’s very misty and out of the midst comes a figure in black. Way far away. 200 yards away. And she comes towards me and it’s Nico. She comes up to my table. ‘Guy!’ ‘Nico!’ ‘You got drugs?’ ‘No. Nico, it’s six years in prison if you’re caught with even marijuana.’ ‘Gotta go. Goodbye.’ Never saw her again.

Q: In your earlier photographic career, you also were in a new music and rock ’n’ roll visual world, where you made just about all the creative decisions on photos, setting, background, and the general shooting schedule. No stylists, creative teams or managers dictating the situation.

A: The artists listened to people like me for setting and placement. I could say to Art (Garfunkel) and Paul (Simon), “I’ve got an idea. Let’s do photos in Franklin Canyon,” near where I was living. New York guys went with me on the concept.

At times, I was doing three shoots a day. The secret to success is to work seven days a week and never take a vacation.

You know, there were no managers in those days that were hardcore managers, who mistakenly thought they were artists and they would pick the photograph, cover and how they were supposed to dress. And that ruined it a little for me and in the day of the CD I kind of dropped out of the record business.

Q: You had worked in a music and record business before it was dismantled, and also did fashion photography in an era when photographers made their own decisions. Did the sense of freedom you had then inform your work that we see now when you shot for clothing boutiques like JAX and Camp Beverly Hills and for West Magazine, Home Magazine, in so many magazines also in Europe and Japan? You saw stylists and models move away for many years now from the natural looks you were capturing with a camera.

A: Most people don’t know that not only was I shooting rock ’n’ roll, but I was shooting other stuff like fashion. These days they’re into their own thing. Now it’s PhotoShop to the max. And that’s OK. It’s what it is. That’s what makes my stuff more fun, I think, because it’s a throwback to another era.

Q: You have taken portraits of Malcolm McDowell for years.

A: Malcolm is one of my best pals. Ted Danson is one of my closet friends in the world right now. But Malcom and I were like brothers. My present wife Leon, Ted and his wife

Mary Steenburgen.are inseparable. We travel all over the world together.

I met Malcolm when he was doing Time after Time. I met him and I kind of knew we were going to be friends. It’s the weirdest thing. I don’t take in that many close friends, ’cause who’s got time? I have hundreds of friends: photographic friends, tennis friends, motorcycle friends. Malcolm and I work on movies together. He’s a great looking guy with a lot of energy, and so much of that energy comes through when you are with him or take a photo of him. He has the energy of the British Invasion. But Malcolm worked with Stanley Kubrick, who was my idol. I wanted to work on one of Kubrick’s films and I was invited to, but not by Kubrick. And Kubrick said, “Absolutely no one shoots stills on my films.” And I wasn’t allowed to do it.

Q: You’ve also photographed Dennis Hooper, who was a neighbor next to your Venice studio.

A: I was friends with Dennis forever. He was a good photographer and an interesting guy. And I knew him when he went out with Michelle Phillips. We were working together to do this picture at my studio and we may have been stoned. How did he become a director? But then again, over the decades, if you look at movies you will see him in little cameos.

Q: And you photographed Jack Nicholson.

A: I’ve done photo sessions with Jack. On the movie Easy Rider was when I got to know him best. He needed some pictures when he was a young actor and he heard about me and I was shooting all the young actors. So I said, “Come on over.” I took a couple of quick head shots. And then after Easy Rider shot him up, he was producing this movie Goin’ South with Harry Dean Stanton that he was going to direct, and he wanted me on the film. So I took photos around that film. And he wanted to be the wolf man. That was his thing. Big beard. He has longevity. And women see him and say, “I’d fuck that guy in two seconds.” He is very sexy. And he’s intelligent. See, one of the things I like about Jack is that he doesn’t go on talk shows. Because that’s the biggest mistake for a lot of actors. It makes them too accessible to the average person and the mystique is gone.

Q: You go way back with Harry Dean Stanton.

A: He has had an interesting career but it is amazing he has never been a household name. Because this guy is a great actor. Great presence. I met him through Jack.

It’s an accident when somebody becomes a major star. Daniel Craig. I’ve seen him around in films for years. He was a small player. Then all of a sudden something happened, some film, Bond, and he’s now one of the biggest stars on the planet. I love films and I like the bad movies people don’t like. For example, Dude, Where’s My Car? One of the most brilliant films I’ve ever seen.

Q: You’ve taken photos of Jeff Bridges for years.

A: We go way back. I knew him before he married his wife. They’re both great. From the first moment I saw him on film I knew he had it. He was a sweetheart. He’s totally handsome, has this great voice and Jeff is smart, educated. Why wouldn’t he be a star?

Q: You lived abroad for years at a time, collected motorcycles, were involved in music publishing, and you never shunned the journey of photography. But why now, in 2014, are your landmark images more popular than ever? And why is the music you documented from 1963 to 1971 so popular now?

We’ve just done a book. I knew, since our first formal interview in 2011 published in Treats! magazine that your photographs with text, could drive a coffee table size volume like Big Shots.

A: What I think is happening is that the kids are relating to the intelligence behind the music of the ’60s and ’70s and they are falling in love with it. The people and their music had messages that they can relate to today. Anti-war, love, let’s all love one another, very, very Buddhist in a kind of weird way. And kids are relating to it. I know my children -- without my pushing it -- found Bob Dylan about fifteen years ago, and couldn’t get enough of him. That’s what started me too. I heard Bob Dylan in New York early on and I wanted to be part of that world.

I’m not surprised by the ongoing popularity of my photo work and album covers. I thought it would never end. I was freaked out that Neil Young wasn’t the biggest star in the world, this poet that was writing these brilliant songs in the ’70s; or that Tim Hardin wasn’t celebrated as one of the great geniuses of the music business. And that upset me.

Q: Can you discuss your equipment over the years and difference in shooting color versus black and white?

A: Some of the black and white I did was on 4 x 5 in my studio. I liked it because of the quality. Like a photo I did with Mick Jagger; I can blow it up to any size I want. Back

then I liked to shoot in black and white. Because it leaves something to the imagination. Now also, you can control it. You can darken the shadows and create some more magic.

“In color, like when I shot James Coburn for “Cosmopolitan” I left so much of it dark in the background to let your imagination work. That’s why some of the greatest directors in history, like Ingmar Bergman, shoot black and white and it’s so evocative and emotional. I’m glad that the Holocaust pictures were in black and white, because they make me cry every time I see them. Unbelievable in black and white. No doubt about it.

Q: You initially shot photos in your studio at your parents’ house, and then your own studio on Sunset Blvd.

A: That was the A&M Records studio that I had. Lighting came in naturally. I had a studio in my home, near Mulholland Drive, up near Benedict Canyon. And I had a giant studio up there with all northern light. I shot actress Leigh Taylor Young there. And that lighting was all natural. All I had to do was have a bounce board on the right-hand side. And I loved that lighting and try to recreate it in my pictures today. So nothing looks lit, unless that’s the look I want. I try and lose the light.

Q: Is it different doing a shoot with a musician as opposed to an actor or actress?

A: Yes. You might have heard this before. Actors and actresses are afraid of the still. Because they’re used to acting emotion and seeing themselves in motion. And that still can carry for the rest of their lives. The still that is like Tallulah Bankhead. That same still is being used today. And it’s frightening. And high end actors -- or actresses particularly -- want photo approval. And that wasn’t the case with rock ’n’ roll. ’Cause these were grungy guys who could barely get up in the morning, had a hang over, looked like shit, and were going out for a photo session. They didn’t care.

Q: What is the difference between photographing female and male actors?

A: Well, male actors generally don’t need makeup. So they are more comfortable just being who they are. If they are very light skinned and light eyed they sometimes need a little makeup. And they are used to doing makeup from all the theater work. So I can put it on them or have my makeup person do it without them freaking out. If you did that to a rock ’n’ roll guy who was in glam rock, they would have freaked out. “You can’t do that!”

Q: What about film stock over the years.

A: Ektachrome. I liked that I could push it. And another thing -- and this is very weird, and I’ve never told this to anybody -- is that I didn’t want my photographs to be crystal sharp, like Kodachrome. There’s a lot of guys who can do that and they do it brilliantly. I wanted to be more painterly and a little soft focus. And I did that intelligently by using faster film that I could push and get a certain grain involved.

Q: You left Beverly Hills and America in the mid-’70s and moved to Spain and Italy, owing partially to the election of Richard Nixon as U.S. President and your being saddened by the Vietnam War. You purchased a farm in Menorca, Spain, and went to school.

After several years of flying back and forth to the U.S., you then returned to Ojai and started shooting once again for the Los Angeles Times, including a series of film directors in their homes and also Ronald and Nancy Regan. You then became involved in magazine publishing.

A: Leonard Koren founded Wet that started as a newsletter, and then it became Wet, The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing. We ran it from 1975-1982. I was the president of Wet, and chief photographer. One of my favorite times. I loved it. We controlled it. We could say to a contributing photographer, “Hey, here’s two pages; do whatever you want.” Nobody ever said that to anybody.

(Harvey Kubernik is an author of 15 books. His literary and music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018.

During December 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Harvey Kubernik and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz.

This century Harvey penned the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish.

Kubernik’s writings have been printed in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats and Drinking with Bukowski. He is the project coordinator of the recording set The Jack Kerouac Collection.

In November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, CA. Harvey literary and musical expeditions are displayed on Kubernik’s Korner at otherworldcottageindustries.com.