Berlin’s Olympiastadion is a brutalist marvel—concrete and colossal, built for spectacle. It’s hosted World Cups, political pageantry, rock gods, and operatic breakdowns. But on June 18, it played host to something else entirely.

Linkin Park, not just back, but big. Their largest headlining show ever. No co-bill. No festival booking. Just six people—and 66,000 fans—meeting on their own terms.

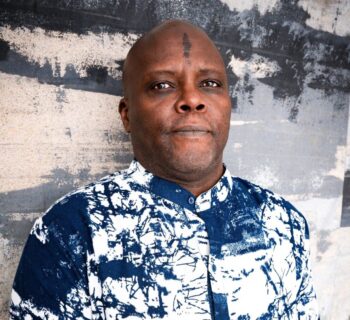

“It was our biggest headline show of all time,” says co-founder, guitarist, and co-lead vocalist Mike Shinoda. “And on this tour, it’s going to be beaten by other ones that are bigger,” he adds, a humble grin sweeping across his face.

That kind of clarity wasn’t always there. Not even close.

To understand what makes this moment so powerful, you have to rewind to what Linkin Park actually meant in the first place. Formed in 1996 in Agoura Hills, CA, the band burst onto the scene with their 2000 debut Hybrid Theory, which became one of the best-selling debut albums of all time. Their signature blend of nu-metal, hip-hop, electronic textures, and alternative rock created a genre-defying sound that resonated with a generation of listeners navigating a new millennium.

What set Linkin Park apart then wasn’t just their sonic innovation, it was their emotional transparency. They sang about alienation, anxiety, identity, and grief, long before those themes were comfortably mainstream. They weren’t just on the charts; they were in your bloodstream. Tracks like "In the End," "Numb," and "Crawling" soundtracked high school breakups, first tattoos, late-night AIM chats. The band’s raw vulnerability met with radio-ready polish meant you could scream them in your bedroom or hear them at a stadium. Either way, they hit home.

After Chester Bennington’s heartrending death in 2017, Linkin Park didn’t just lose their frontman, their bandmate, their friend. They lost their axis—the voice who embodied catharsis in its most visceral form, the voice, able to shift from haunting falsetto to full-throated scream in seconds, that became an emblem of emotional volatility. “[There was] obviously a lot of grief and uncertainty,” guitarist Brad Delson says.

No quick rebound, no tidy timelines. The silence was real, and the band let themselves vanish from the spotlight, collectively and individually. And for a while, it felt permanent. “We definitely gave ourselves time to just sit in the grief and heal—as much as one does,” Delson says. “Eventually a spark emerged to begin a new chapter and making art anew, and yeah, it's been really fascinating and fulfilling, and I'm really proud of From Zero, and the show and the humans involved.”

Shinoda, Delson, Joe Hahn, and Dave "Phoenix" Farrell didn’t rush a rebound. They didn’t even know if one was coming. “There were so many weeks and months where it was like, ‘Well, this is doomed; it's just not going to happen. I don't see how we're ever going to solve all the things that are wrong with trying to get back out on the road,’” Shinoda says. “We’re going to have to find a singer, and nobody's going to be able to live up to that, even if they were good, it's going to be too much pressure, the fans aren't going to accept it. No one's going to like it… That sounds like a recipe for disaster.”

There was no master plan, no dramatic Pinterest vision board. Just small steps, instinctive choices, and one hell of a willingness to leap into the unknown. The question was never how to move forward; it was if they even could. So, they didn’t think about the whole mountain. Just the next foothold. “Having a band with the history that we did—that we have—and having it effectively fall to pieces, and then picking it all up and trying again, was—is—so difficult,” Shinoda says.

When asked what went into making the Linkin Park resurgence happen, Shinoda laughs and says, “God. So many things.” And it’s true—reigniting a force like Linkin Park means reckoning with legacy, loss, and the weight of millions who still care. Shinoda uses a saying: How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.

When Linkin Park reemerged onto the scene in November of last year with From Zero, their first full-length album since the loss of Bennington, the world didn’t quite know what to expect—and neither did they. “Even like 18 months ago, I don't think we would have known where we'd be at all,” Shinoda admits. “The band came into focus while the album came into focus. When we started this process, we didn't know who the band members were and we didn't know what the music was going to be like…we kind of just decided to just keep moving and keep our minds open to what seemed interesting, or what seemed like the right choice, and we arrived at the body of music that became From Zero, and the lineup as you see it.”

That first step looked like curiosity. Then studio time. Then something unexpected: a spark. “We kept our expectations… I wouldn’t say low, but we tried not to put all the pressure of the whole thing on every small decision,” Shinoda says. “One tiny little moment at a time.” That leap landed them in a new chapter: one marked not by erasure or reinvention, but by evolution.

One bite. One step. One breath. Eventually, those moments became momentum.

Two new collaborators emerged—not in a press release or bombshell Instagram drop, but slowly, quietly, and organically. Enter Emily Armstrong, a powerhouse vocalist with emotional grit and range, and Colin Brittain, a longtime producer who’d left his own front-of-stage days behind.

Both Armstrong and Brittan were, at first, only names on session calendars. “It wasn’t like, ‘Hey, let’s go find this or that piece,’” Delson says. “It just kind of naturally unfolded.”

Brittain puts it more romantically: “It was more of a long dating process... then there was the engagement process... and then it was, ‘Hey, Emily and Colin, will you go learn these new songs? [Then it was] ‘hey, we really like you guys, and we're not looking for anyone else.’” The drummer/producer called it “Exhilarating and terrifying and I guess it was sort of like an existential crisis.” But, ultimately, “It was actually quite good for me…[because] it made me a better person, or at least a more patient person.” And when it got to a point where he woke up every morning thinking “Oh my god, like, this could actually happen,” that’s when the excitement crystallized into conviction—when he stopped second-guessing and started preparing for what was next.

Before joining Linkin Park, Armstrong had already built a reputation as one of rock’s most incendiary frontwomen. As the lead singer and co-founder of dynamic alt-rock band Dead Sara, she carved out a career on raw power and emotional precision—her vocals both jagged and operatic, capable of rupturing silence and commanding chaos. Dead Sara’s breakout track “Weatherman” introduced her as a feral, full-throated force, and years of grinding club tours and festival sets sharpened her into an unflinching performer. Offstage, she worked across genres, including collaborations with Courtney Love, building a toolkit without ever diluting her intensity.

“When I first met Emily, she just felt kind of familiar, even though I didn't know her,” Shinoda says. In 2019, Shinoda and Armstrong got together, mainly just to meet each other and write. After a couple of sessions, a few years went by before they reconnected. “When we were working in the studio, we were inviting her in once in a while. It's like, maybe she'd come in, and then weeks would pass [before] she'd come in again, and then it'd be [that] less weeks would pass, and then it was days,” says Shinoda.

But when he heard Armstrong’s vocal scream during the bridge of “Unshatter,” it pulled the whole thing into focus. “There’s a rare connection I have to that type of performance. I don't like a lot of bands who scream,” he says, “It doesn’t feel genuine to me, it feels like technique.” But with Armstrong, “it was immersive and emotional and real. And that was just, for me, was one of those moments where, ‘oh, I connect with this,’ and it doesn’t feel like it's trying to be Chester. It doesn't feel like it's trying to be Linkin Park. It just felt like her, and I really love that about it.”

Armstrong wasn’t the only one with something to prove. Brittain had spent years behind the board before jumping back in the saddle of performing. “When I moved to L.A. I started producing, and I had a fair degree of success with my production career, I just thought that that was sort of where the universe was pulling me,” he says, chalking it up to: “you're not meant to play the biggest stages. You're meant to make the biggest song so then other people can play them.”

But joining the band wasn’t just about drumming. It was about synergy. Even as a fan, Brittain told Shinoda, “We need a giant like Linkin Park. That's so important throughout the generations, to really come back and, you know, lead the way for people, because it's one of the only bands that I could think of that has this kind of a visceral, emotional impact on so many people around the world. So it was something really important to me, even as a fan, not as a band member.”

The band didn’t “audition” anyone; they followed that spark. And where it led was From Zero.

The album, Linkin Park’s first full-length LP since One More Light, didn’t start with a grand premise or genre manifesto. “The album was driven more by intuition than concept or overarching conceptual direction,” Shinoda says. “We were just vibing and whatever the song wanted to do, we chased that down.”

That chase led to a tight, propulsive record layered with emotional honesty and signature LP textures: hard-charging guitars, electronic flourishes, and raw, lived-in lyricism. It’s not a return to Hybrid Theory. It’s not A Thousand Suns 2.0. Less a return than a reorientation. It’s familiar, but forward. Introspective without navel-gazing. Big without posturing. Delson puts it simply: “We gave ourselves permission to return to things that were seminal early on—creatively for us and juxtaposing those with surprising new elements gives From Zero its richness.”

The songs came in waves. Then floods. As always, the band wrote compulsively—dozens upon dozens of songs, hunting for that absolute 10. “It's like iteration. Constant iteration, until you get to that undeniable place, and that can take a really long time.” They’ll write 50–100 songs to get to 10 that “are great.”

“You really gotta love [what you’re working on] in the studio to have the conviction that this is something important to share,” Delson says. “If we’re not listening to it instead of everything else in the world…we wouldn’t expect anyone else to care.”

Delson, often referred to as the quiet architect of Linkin Park’s sound, lights up when talking about studio work. He likens it to surfing—something he doesn’t actually do, but feels emotionally connected to. “Every wave is different. There're always unknown questions to be discovered and explored, just endless possibility.”

That commitment to detail—obsession, really—is the band’s creative religion. It’s how they’ve stayed unpredictable for two decades while never losing themselves.

Of the new album, Shinoda says, “There's so much of Linkin Park's DNA in it…Because of the combination of new blood and the fact that our band has, to some degree, I don't want to say avoided, but you wouldn't get very much old school Linkin Park in most of our material after 2007. There'd be glimmers of it, but it wasn't full on. We were always trying to take our DNA and make it more, ‘how can we take this thing that we do and make it more different?’ Or, ‘how can we completely avoid it all together so as to not be repeating ourselves with the new blood?’ It's almost like when you paint with some of the old colors—it felt totally new because you've got completely new personalities and points of view in the mix, like when Emily sings a song like ‘Two Faced,’ it doesn't sound like a Hybrid Theory rip-off to me, it just sounds like Linkin Park.”

It wasn’t just the music that leveled up. From Zero’s visual identity is as carefully crafted as its track list. The standard cover features a small, abstract icon—a mysterious dot in a seemingly digital void. The deluxe version? It explodes into a textured, full-frame world built by hand (literally).

“There were years of creativity that went into From Zero,” Delson says. “And a tremendous amount of richness in the visual art…The art isn't an afterthought for us, the art, the visual art, is really a part of who we are. And so, in collaborating with our long-time director Frank Maddocks, Joe and Mike went about taking these icons. And people think that these are digitally created, but they're all made by hand—those are physical pieces that were submerged in and immersed in solutions and then photographed. So we worked with this guy, Josh Foster, creating all these chemical textures. And a talented photographer named Brian Ziff actually photographed these things.”

The result isn’t just another album cover, it’s a painstakingly built visual language that echoes the band’s sonic ethos: boundary-blurring, genre-defying—physically real but emotionally surreal.

It plays on the motif of appearance versus reality, Delson explains, raising questions about “What’s digital [and] what’s analog... And if we're successful, oftentimes you don't know which is which.”

That tension is the heart of Linkin Park itself. If From Zero was the risk, the live shows were the gauntlet. “When we put out those songs, it was like, ‘God, I hope someone likes this,’” Shinoda says. “In 24 hours, you’ll know if everybody hates your guts.”

“We launched all these plans before anyone heard anything or saw anything…There was so much pressure around that launch. It was face-melting,” Delson says of their high-wire return act. “Arenas and stadiums were locked in before we’d even played a note. It was a miracle no one knew.”

Especially about Armstrong. She literally had to hide—even coming to the studio was kept a secret. “I told her it was almost like she was on The Bachelor,” Delson says.

But the secrecy paid off, resulting in a surreal response. The cameras were already rolling when the lights dimmed for Linkin Park’s long-awaited return show—broadcast live to fans across the globe. Dust covers veiled the instruments on stage like furniture in a long-shuttered house. And like the fixtures, the fans had been waiting. As the first notes rang out, crew members lifted the sheets and the band emerged, already wired with decades of history, grief, and expectation. “It’s good to see you again,” Mike said, beaming. But behind the scenes, something else had been unfolding: a gamble. New music. New members. And a fanbase that didn’t know what was coming.

The livestream revival was electric and raw. And the fans? They showed up. En masse. “We were really taken aback at how instantly the new music connected with people all around the world,” Delson says. “The velocity of traction” with new songs like “The Emptiness Machine” didn’t just connect, it exploded. “[It] was a global top streamed song, like, immediately, and then for months. And I'm not even saying in the rock genre, in like, the main page of most streamed songs, it was in there, and you don't even see rock songs in there,” Delson remarks.

“When we cut into ‘Faint’ or ‘Casualty’ or ‘Emptiness Machine’ or ‘Up From The Bottom,’ people know every word, and it's just as loud as the old songs. And then you're seeing mosh pits and people just really having an emotional connection to the song… it’s a cathartic experience,” Brittain says. Many of those songs “didn't exist one second ago,” Delson adds, “[and] that is like magic.” Having tracks off From Zero already punching with the same weight, volume, and connection of old anthems confirms that the band hasn’t strayed from what defines them, only reaffirms that their “chemistry is super, super rare.”

Ask fans what they think Linkin Park is, and you’ll get a dozen answers: A nu-metal icon. A crossover blueprint. A band that raised them, saved them, soundtracked their coming-of-age. Ask the band what Linkin Park is, and you’ll hear something else: a group of people still chasing that spark driven by human connection.

The band’s core ethos remains as grounded as it ever was: It’s never about the scale or spectacle, but the authenticity and shared emotion that makes every performance matter. “Whether we're playing for 1,000 people or playing for 50 or 75,000 people… the energy to me is almost the same,” Brittain shares. “As long as the people who are there are connecting with it, I don't really care even how many people it is.”

But that authenticity can sometimes get obscured by the sheer scale of the band’s success. “Because the band is so big… it's easy to forget, like, ‘oh, this band is actually sitting down with an instrument and writing you a story,’” Shinoda says.

“People tend to think that there's some kind of a formula or big industry… that's behind the scenes, or something like that, that's pushing it into this thing,” Brittain says. But in reality, it’s “organic and democratic. And it's a band. It's a full group of people with everyone's opinions—and everyone's opinion matters—and that energy comes from the band members, and it's filtered through the band. It's filtered through the taste of the members in the band. And none of it is put on. It's all taste driven. Yeah, there's really no decisions that are made based on commercialism. It's all just what we like, and, as far as I can tell, it's always been that way. I can't imagine it not being that way.”

“It's not just about it being commercially successful. It's about everybody in the band standing on stage and loving what they made” Shinoda says. “I want every single person to stand behind it, that's important to me.”

If it’s not undeniable to all of them, it doesn’t make the cut. “We really try not to ever convince anyone else in the band that what we like, they should like,” Delson says. “[It] really starts again with the six of us in the studio,” he adds, “whether it's the track first or the song of it all first, ultimately, everything is in service of the content of the song, of the idea that we want to get across.” That bar keeps them honest. Keeps them pushing. Keeps the art alive.

Veracity remains the band’s north star—even when that means resisting shortcuts. Shinoda describes a kind of intuitive editing. “If I make a demo and I know it’s unfinished, I listen to it and I already know what criticisms [the band is] going to have of that demo before they even say it,” he says. “I know them all so well.”

But with Armstrong and Brittain, it’s different. “I don't know what Emily is going to say. I don't know what Colin's going to say. Because I haven't written with them for long enough to guess it,” says Shinoda. “That just makes it a little more challenging. It [also] makes it really fun.”

Brittain, for his part, is an analog-gear-head with a producer’s restraint: He knows when not to play. And that perspective is shaped by his work outside the band. “It’s more about the song… rather than being a show-off drummer,” he says. His goal in this discipline, always, is for the team to sound cohesive together. “I just want this [song] to sound great, I want this version of the record to come across to the listener and to the audience as powerful and connected as I can.”

“When I'm producing other artists, I'm sort of in that role where it all kind of funnels through me and I feel a little bit [more] responsible,” he says. “So I think, in some ways, it's a lot more freeing to have somebody like Mike who's so confident in where the song is going to go, because that way I can almost be a little bit more outside of the box and try ideas that are maybe even a little more fearless than what I normally would do if the situation was reversed.”

Recording in the studio is one thing, translating those tracks into a live performance is another entirely. “You almost have to relearn the song,” Brittain says. “You’re in the studio and you’re experimenting around. Oftentimes, we'll track drums in just a handful of takes, or guitars in a handful of takes, and you're moving so fast you don't really know what you'd even played.” But on stage, “one person might rush, another might drag, and you’ve got to figure out how to exist together in that song.” There’s an intimate physicality to it, “It’s like learning to breathe together,” he says.

What makes this new chapter resonate isn’t nostalgia, it’s motion. A band once paralyzed by heartbreak and uncertainty is now lit by gratitude. Their stage energy is massive but measured. Intentional. Alive. Before every show, they huddle. “We regularly try and verbally express gratitude for each other and for the things that happen,” Shinoda says. “[Even] if we have something that doesn't go right, we learn something from it. We try and express gratitude for those things out loud so we can really stay focused on the connection between all of us and the fact that everybody participating in that is valuable.”

That connection is their throughline. Not the polish. Not the platform. The pulse.

“We always look at it like, if all that stuff was taken away, would the show be successful?” Shinoda says. “Would I be proud of it and feel like it's going to reach people the way it was intended to, even if there's no bells and whistles?”

It’s a mindset he’s carried since his early days—like when he wore blue goggles and gloves onstage at the Whisky a Go Go, trying “to make people feel like they're seeing something bigger than the little thing that it is.” Decades later, he finally has his answer.

“It takes a while to get to a point where you can get up on stage and be more naked and just be like, ‘okay, I'm just a dude, I'm just a person, human being up here sharing these songs and connecting with you,’” Shinoda says.

So what does “From Zero” mean?

It’s not just about grief. Not just about rebuilding. It’s about the radical act of beginning again—without pretending the past didn’t happen. They’re not trying to erase anything; they’re bringing all of it with them like carryon luggage. If Linkin Park’s early years were all about volume—sonic, emotional, cultural—this new era is about intention. From From Zero to its deluxe reissue, every beat, riff, and pixel of album art has been shaped by something raw, deliberate, and very human. Call it a rebirth. Call it a homecoming. But don’t call it a comeback.

For now, Shinoda just wants to “stay focused on the purity of why [we’re] doing it, and what it's for.” Delson will keep chasing “moment[s] of discovery” in the studio. And Brittain, well, “I hope it doesn’t get old.”