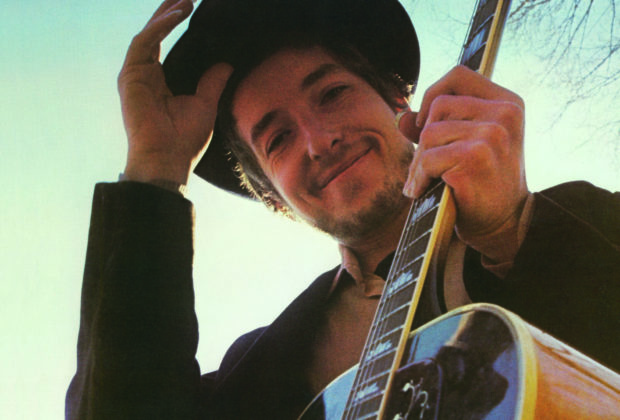

50 years ago in April 1969, Bob Dylan’s album Nashville Skyline produced by Bob Johnston was shipped to retail outlets. The Columbia Records product was available on LP, reel to reel and cassette configurations.

Johnny Cash contributed the back jacket text to Nashville Skyline which won a 1970 Grammy Award for Best Album Liner Notes.

"With Nashville Skyline,” record producer, author and deejay Andrew Loog Oldham told me over a 2007 dinner, “Dylan continued to box himself into the arena of The Beatles and, in particular, The Rolling Stones and show us all not only how good he was at the same game, but how to change and improve it."

During April, Bob Dylan is acknowledging album’s anniversary with an announcement of his Heaven’s Door whiskey company opening up a new distillery in downtown Nashville to be named the Heaven’s Door Distillery and Center for the Arts. Dylan’s own paintings and sculptures will be on display that will incorporate a restaurant, performing venue and a whiskey library.

Bob Johnston’s resume includes Johnny Cash’s Folsom Prison and San Quentin live LP’s, the first three enduring albums of Leonard Cohen: Songs From A Room, Songs of Love and Hate, and Love Songs. Johnston also produced Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde On Blonde, Self Portrait, New Morning and John Wesley Harding.

Johnston was born in 1932 in Hillsboro, Texas.

His career began as a songwriter. He eventually held a staff writing position at Elvis Presley’s Hill & Range Music and often reviewed potential Presley demos and songs earmarked for Presley movies in 1964 and 1965. In addition, Johnston had peripatetic stints talent scouting for Kapp Records and arranging for the incredible Dot Records label. Arthur Alexander did one of Johnston’s songs and so did Mac Curtis, before Johnston joined Columbia Records in 1965. That year he produced Patti Page’s charming yet scary top 10 hit single “Hush, Hush Sweet Charlotte.”

Johnston produced the music for the films Little Fauss and Big Halsy, and McCabe and Mrs. Miller, featuring the music of Leonard Cohen backed on occasion by the members of the Kaleidoscope.

Bob Johnston was initially introduced to Dylan in 1965 when he was called in to replace pivotal record producer Tom Wilson to complete Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited album in New York City. “I was working with Dylan in New York and I flew in Charlie McCoy from Nashville, introduced him to Dylan,” Johnston told me in a 2007 interview, “and the first thing we cut was a version of ‘Desolation Row,’ with Dylan on acoustic, Charlie on electric and Harvey Brooks on bass.

“I was standing by the sound board and I said to Dylan ‘Listen man, you ought to come to Nashville sometime. I got a fix up down there with no clocks and the musicians are fuckin’ great.’ ‘Hmmm.’ He’d never answer you, just go ‘hmmm’ like Jack Benny… So I finished Highway 61 Revisited and then Dylan called me about six months later and he said, ‘Man, I got a bunch of songs. What do you think about going to Nashville?’ ‘That’s what I was talkin’ about!’

“In 1966 we went down there for Blonde On Blonde.

“Dylan and I were notorious for using first takes,” Johnston revealed. “He liked to get it out of his head. I don’t see any sense in doing it over and over. They knew what I wanted them to play not what I gave them. That’s why they were there. When I started with Dylan he said, ‘my voice is too loud.’ Good enough. So I turned it down. Then I’d turn it up. ‘Man, I can’t hear myself’ and had that voice out there. Finally, we got to the place where he said ‘I can’t hear myself.’ cause I’d brought it so low. So I told him I’d take care of it and never asked him about it anymore and turned everything up and had that voice out there.”

Fast-forward to 1967, after the notorious motorcycle accident in July 1966 that, among other things, sidelined Dylan (at least in the public eye) for a better part of a year. Bob Johnston met up with Dylan again at a Ramada Inn in Nashville, Tennessee before working on John Wesley Harding together.

“He played me some songs and asked, ‘what do you think about a bass, drum and guitar?’ ‘I think it would be fuckin’ brilliant if you had a steel guitar.’ ‘You know anybody?’ ‘Yeah, Pete Drake.’ He was workin’ with Chet (Atkins), so I got somebody to take his place and brought him over,” Johnston ruminates. “Pete said, ‘Can I play some rock ‘n’ roll?’ And I told him, ‘That’s what you’re here for.’ Charlie McCoy played a lot of instruments on that album. He played four, five or 20 instruments on every record.

Johnston, as he did previously in the Nashville sessions for Blonde On Blonde, John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline took steps to remove the studio bafflers, a floor space dividing device used to prohibit microphone leakage and the instruments of the musicians from bleeding into each other’s separate sound booths during the sessions.

“I’ll tell you something else I did recording Dylan,” Bob Johnston boasted.

“What I did was put a bunch of microphones all over the room and up on the ceiling. I would use echo when everything got through and I could do that as much as I wanted. I wanted it to sound better than anything else sounded ever, and I wanted it to be where everybody could hear it. And I don’t know what Dylan would have been if he stayed in New York with those people, and been mixed like that. And I know he would have never done that shit like he did in Nashville,” Johnston insisted.

“Everybody else (at the time) was using one microphone, which means you have to sacrifice something. If you’re gonna have a band, you can’t have the band playin’ full tilt. If you’ve got him in the middle you can’t understand everything with different people (engineers) in there raising the guitar up, raising the drums up, and shit like that. What I always did was that I had three microphones because he was always jerking his head around, and I put the microphone on the left, center and right and it didn’t matter where in the fuckin’ room he went. And then I’d mix and start on the left and go all the way over on the right,” he stressed.

“So I’d usually have the piano on the outside left, without any echo. And then I’d put the echo on the right side. And then I’d have one of the guitars on the right and put the echo on the left…and then I’d match it all alone and brought up everything even so they could fight it out. And then that’s the way the band was. They didn’t have to raise this and lower this, and 15 people sitting around doin’ all that shit. The band was there and he was full-tilt. Then you could go any place in the room and understand him…and I never heard another word from him about anything.

“I would place glass around Dylan for recording,” volunteered Johnston. “He had a different vocal sound. I didn’t make his different vocal sound. He always had different sounds on. I never wanted to be (Phil) Spector… and while the rest of the world was doing an album as big as Blonde On Blonde, which everybody was - the more musicians they could get, the better it was. (But) we went in with four people…in the middle of a psychedelic world!

“I always had 4 or 8 speakers all over the room and I had ‘em going. The louder I played it the better it sounded to me. This is the way I really did it.

“I had Cash in the Columbia Music Row studio and thought it would be nice to get Dylan in there, too and I didn’t say anything to them. Cash was in the studio and Dylan came in. ‘What are you doing here?’ ‘Gonna record.’ ‘Well, I’m recording too.’ So, they invited me to dinner, but I said ‘no thanks.’ And when they returned I had a ‘café’ set up outside with microphones and their guitars, and they came in, looked at the lights, sorta smiled at each other. June (Carter Cash) was there. We did like 18 tracks.”

Those sessions yielded the duet “Girl From The North Country” heard on Nashville Skyline.

“As a songwriter, I wrote songs, too, (but) Dylan changed the world. Every song he did I loved. I was a Dylan freak and I knew he was changing the world. I knew he was changing the society as we knew it. And I knew Paul (Simon) was too.”

Charlie Daniels is the multi-instrumentalist who played on Nashville Skyline and other Johnston-produced endeavors.

“When Bob Johnston moved to Nashville in 1966,” Daniels recalled to me in a 2014 interview, “he called me and said, ‘Why don‘t you come to Nashville?’ And I always wanted to live there and packed up in 1967. He had just done Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde. All the good things that happened to me in the early days were because he was a cog in the wheel. One thing that needs to be said about Bob Johnston and bringing people to town like Dylan and Leonard Cohen,” explained Daniels. “There was skepticism about Bob coming to Nashville because he was taking the place of a legendary producer, Don Law. Who was an institution in town.

“Here’s this guy Johnston from New York, who had been doing Simon & Garfunkel, Bookends, Dylan, and now Leonard Cohen, who were not really thought of as being country. But the first thing Bob did when he came to town was to do a number one song with Marty Robbins. And in ‘68 produced the albums John Wesley Harding, Flatt & Scrugg’s The Story of Bonnie and Clyde, and of course, Johnny Cash’s live album at Folsom Prison.

“He had gained credibility. He was also at the same time, bringing Al Kooper, Dylan and Leonard Cohen into town who had never lived here. Dylan recorded in Nashville in 1966 for a while, but it was he’d come to town, do his stuff, and leave. Dylan happened to record in a studio in Nashville and worked in it.

“And, hassles with long hairs, prejudice, racism, didn’t exist in our world,” underlined Daniels. “In the sixties everything was pretty much in the throes of a lot of upheaval. This was back in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s salad days, when he was going around, doing things that a lot of people didn’t understand it or didn’t get it. I was in Nashville when Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis. The thing was, when you’re goin’ in to make music that is a whole other thing.

“Nobody wanted to work in the big studio until Bob Johnston came to town and basically took it over,” he remembered. “Nobody else wanted to be there. He worked with it, got engineers he enjoyed working with like Neil Wilburn, and he actually brought an engineer from New York with him when he first came down.

“The Columbia Studio was union. In Nashville, in the studios, you had to have the machines to be a certain distance away from the boards so the engineer could not work them both. But the thing I remember mostly about Studio A., the big studio, it was the new studio. The old studio, the Kwansit Hut, was the legendary studio where the hits had been cut. Everybody wanted to work in that room.

“With people like Cohen and Dylan…Most of the Nashville sessions, the country artists they would bring a demo in, they’d play the demo, you play it like the demo, you may change a key on it, but basically it’s gonna be the same thing, how they want the demo. So you’re playin’ pretty much inbounds.

“With Leonard and with Bob Dylan, and it was on a Dylan, and Charlie McCoy was the band leader. And how much do you want him to play? How many bars? How much do you want him to do? And Dylan replied, ‘all he can.’ Well that really describes what this is all about.

“Cohen and Dylan were singers and songwriters. They write their songs, they weren’t coming in from a music publishing company. It was a lot different because there is no hurry. We went into the studio. Like with Nashville Skyline we had about fifteen sessions booked to do it and probably only used half of them and it was over. Everybody got so in to what they were doing. If you listen to Dylan, the stuff before and after, Nashville Skyline stands out. It’s a different kind of record. The material was a little different and dealt with different themes.

“Nashville Skyline and John Wesley Harding are two different records to me,” Daniels posed. “The Nashville Skyline record was a departure for Dylan. It was just so different than anything I had heard him do. ‘What else you got Bob? We got this one done.’ And of course, Dylan is a big first take guy. If you can get it on the first take that’s how he wants it. And I like that about him. I’m the same way.”

50 years after Nashville Skyline was first commercially issued, I asked several writers, in April 2019 about the recording.

Michael Hacker: To most Dylan fans in 1969, country music was the devil’s music, the devil being the conservative majority that still ran things in America, even worse, country music was identified as redneck, read ‘racist’ music. That may not have been true or correct, but it was the perception of a lot of young people in America at that moment.

“In spite of all this, the album became Dylan’s best seller ever, anchored by the hit single ‘Lay, Lady, Lay’ which reached Number Seven on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. On that song, worship must be paid to the late, great drummer Kenny Buttrey, for the insanely creative beat he taps on bongos that kicks the song off and the drumming he does throughout that really holds the song together. It’s a beautiful song with beautiful accompaniment, and it sounded nothing like Dylan ever did before.

“Even today, fifty years later, people still get hung up on the voice Dylan used for Nashville Skyline. What I think they’re missing is how evocative and beautiful this voice is, and how it shows Dylan’s amazing control of his vocal instrument.”

Dr. James Cushing: “I was not surprised when I first heard Nashville Skyline. This is an extension of what ‘Down Along The Cove’ and ‘I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight’ from John Wesley Harding had delivered.

“Dylan found that it was possible for him to craft simple love songs after he had been an ambiguous messenger. Only ‘I'll Be Your Baby Tonight’ has a ‘chorus’ or ‘middle-8,’ the rest of the songs have only verses. The composition of the songs suggests sparseness, avoidance of the repeated element, and a focus on the narrative thrust.

“At the time (spring 1969), as I remember well, Nashville Skyline was the first ‘letter from an old friend’ in 18 months, and so was enthusiastically welcomed.

“I remember playing it over & over again, but feeling confused about the fact that ‘Peggy Day’ and ‘Visions of Johanna’ were both by ‘the same guy.’ No, they weren’t, not really — and while one part of me trusted Bob as an artist to do something surprising, authentic, and compelling, another part wanted more of the verbal complexity and thin-wild-mercury of the previous four albums.

“He simply does not sound especially interested in what he’s doing. There are little vocal sweetness on the songs, all right, and ‘Lay Lady Lay’ and ‘Tonight I’ll Be Staying’ have a melodic magnetism that recalls the man’s genius. But Nashville Skyline’s eight new songs barely total 20 minutes, and that’s a problem — the album’s almost over before it begins.”

David N. Pepperell: I liked John Wesley Harding but was terribly disappointed in Nashville Skyline.

“Could this be the same man who electrified the world - in more ways than one - on Blonde on Blonde?

“This guy sounded like a poor man's Don Gibson!

“ My feeling about this album haven't changed in the intervening years - it's too short, there are far too many dud tracks with only one, ‘I Threw It All Away,’ anywhere near the standard set in Bob's 1962-1966 albums.

“He is a man who constantly seems to want to destroy his heritage and this album was one of the first - there have been many since - that sought to do that.

“Two stars out of five for me.”

Daniel Weizmann: One of the greatest things about Dylan's artistic personality is the way he turns it like a Rubik's Cube, turns it and turns it and--voila!--some new aspect that was secretly there all along suddenly gets a full face in a way that throws the listener for a loop. For instance, Dylan was always a rock and roller, long before he went electric. Of course he was. That's what made the Newport plug-in move so disarming--it exposed the unobservant and forced them to acknowledge that he wasn't breaking away from anything. Quite the opposite: he was digging down deeper into his essence.

“In the same way, Dylan always had the romantic country balladeer in him, long before Nashville Skyline.

“You sort of knew that, listening to songs like ‘Boots of Spanish Leather’ or ‘Love Minus Zero.’ But you didn't expect him to open the newest LP by skating out on a duet with Johnny Cash! Or to croon the heartwrenching simplicity of ‘I Threw it All Away’ or ‘Lay Lady Lay’ without even a hint of the pared down psychedelia of John Wesley Harding.

“The intensity of Dylan's artistry is such that, when he embodies himself, he goes for the total person.

“I still can hardly believe Nashville came out in early '69, that rickety, bruising rollercoaster of a year. Dylan's bravery in making this record at that time is also jarring. With the onslaught of ferocious modernism, orgiastic liberation, and cultural rancor, he tips his hat with a friendly smile and graciously asks for a ride to the country and to the human heart.”

HARVEY KUBERNIK is an author of 15 books. His literary and music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018.

Harvey Kubernik’s The Doors: Summer's Gone has been nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections Awards for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research.

During December 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz.

This century Harvey penned the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish.

In November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California). For more, visit cavehollywood.com.