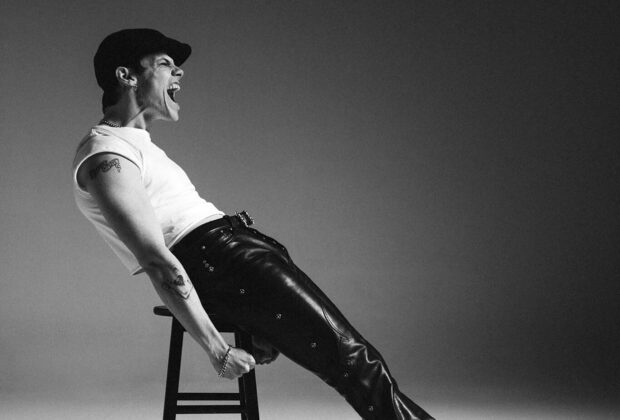

"The last time I was here, I knocked my teeth out on this stage and it was crazy. I was 19, just been signed to Interscope, and it was a real turning point. Being in this room basically feels like that again,” declares Dominic Harrison, A.K.A. Yungblud, standing onstage at Hollywood’s world-infamous Viper Room. He’s about to preview “the most ambitious project I've ever made, by miles” for a private audience of music-biz tastemakers, and he’s wearing a natty three-piece suit for the occasion, calling this “the biggest moment in my life.”

“I have no other choice but to do this,” Harrison continues—his charismatically kohl-eyed stare, motivational-speaker-like evangelism, constant F-bombs, and just sheer force of will managing to capture the full attention of a weeknight industry crowd that would normally be primarily focused on draining the party’s open bar. “I really do feel like it is a turning point for me. And it's a risk. But I feel like risk is an artist's biggest weapon. I don't know how the fuck this is going to go. You're either going to love it, or you're going to fucking hate it. But I love it. I fucking believe in it. I believe it's where fucking rock music should go. I believe it's going to be a fucking flag in the ground.”

And with that, Harrison presses play on his fourth album, Idols. To describe what follows as “epic” would be a huge understatement. The album’s gauntlet-throwing lead single—a sort of please-allow-me-to-reintroduce-myself statement song called “Hello Heaven, Hello”—is a nine-minute, multiple-time-signature, three-act mini rock opera that practically makes Meat Loaf’s “Bat Out of Hell,” Guns N’ Roses’ “November Rain,” or My Chemical Romance’s “Welcome to the Black Parade” seem like exercises in economy and restraint. And it’s accompanied by a cinematic music video starring a shirtless, horseback-straddling, Prometheus-winged Harrison posing and preening against black-and-white backdrops of cranked-to-11 Marshall stacks and in Discovery Channel-worthy aerial shots of medieval snowscapes. It would almost seem like a parody, if it wasn’t so clearly sincere and undeniably great. It’s utterly unexpected from the new-school punk/pop provocateur, and so defiantly, refreshingly radio-edit-resistant that Harrison jokes, “Yeah, fucking Tom March [the president of Yungblud’s label, Geffen Records] had a heart attack! But I really think rock needs this.”

Three months later, Harrison is animatedly chatting with Music Connection about this years-in-the-making passion project, and his excitement—and his conviction that he’s doing the right thing—is even more intense. “Everyone was like, ‘You really wanna come out with a nine-minute song?’” he says with a laugh. “But I feel like right now we're being told to consolidate everything and we're taught to make it digestible. I was like, ‘Fuck that! Let's go the other way!’ I didn't give a fuck about is this going to be played on the radio, or will it work in a world of streaming, or so it can be put on this or that playlist, or all those stupid questions when you're trying to make an album. The boundaries placed on art often make it mediocre, because it's not supposed to be that way. It's not supposed to be so paint-by-numbers. I'm like, even if it's detrimental to whatever the fuck career I've got, I just want to make what I want. That's what I did on my first album, and that's why I got any sort of remote success whatsoever. I think in the past, the only parts of my career that I regret, or that maybe weren't real, were when I listened to other people too heavily. So, fuck it.”

Idols is actually the album Harrison wanted to make—“an album without form”—way back in 2021, as the follow-up to his sophomore effort Weird!, which topped the charts in his native U.K. “I wanted to have vocal solos. Guitar solos. An orchestra. Time changes. Ten-minute songs. Something that couldn't be made in a bedroom. I wanted to make an opera! That was where my gut wanted to go,” he says. But Geffen’s powers-that-be didn’t share his bold vision. “I remember taking this idea to the States, to the label, really excited about what I was making. And then the big bad wolf comes calling and it's like, ‘No, no, we can't do this.’”

So, Harrison put those grand plans on indefinite hold and released the more commercial and conventional Yungblud. It was a success, but he felt like a failure. “That album had gone No. 1 in seven countries, but I'd compromised. I'd listened to other people. I was like, ‘Fuck. I could have done better.’ There are some great songs on that record, but I could tell I was lost,” he says. “I felt like everyone knew what ‘Yungblud’ was, like I'd almost become a caricature of this fucking thing I'd created in my head. I think that's why I called that album Yungblud—because I was trying to hold on for dear life. That process was literally me trying to figure out what the fuck that name even meant anymore. And at the end of that campaign, I was like, ‘What the fuck am I going to do?’”

What Harrison did, specifically, was sequester himself in a rumored-to-be-haunted Tetley beer brewery in the north of England, 20 minutes away from his childhood hometown of Doncaster, with longtime trusted collaborators Matt Schwartz and Adam Warrington. And he decided to grow “the bollocks to not take no for an answer.”

“My imagination is really large, and in the past I think my biggest fight has been to dim down my imagination. People have always wanted me to chill out and not be too this or too that—or too anything. With this album, I wanted to let my imagination be limitless in terms of time, in terms of interludes, in terms of feeling,” he explains. “And I think it really does show when you hear it. It's like, ‘Fucking hell. This is wild.’”

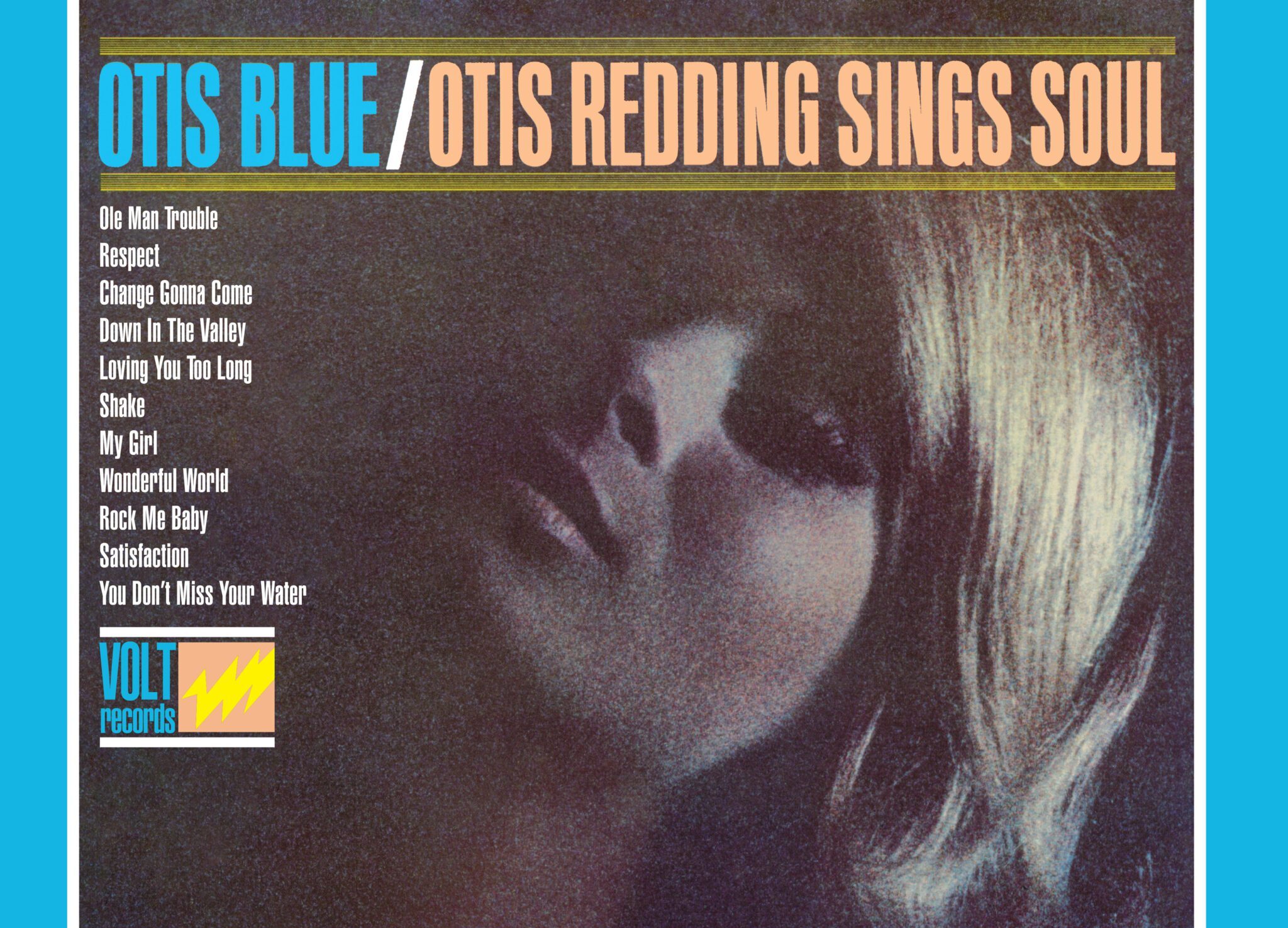

A wild, potentially frontloading album-opener like “Hello Heaven, Hello” would be a daunting act for most artists to follow, but it’s probably obvious by now that Yungblud is not like most artists. Sometimes he does wear his influences on his Burberry sleeve—for instance, the Cool Britannia of Idols’ cheeky second single, “Lovesick Lullaby,” evokes Parklife-era Blur, complete with Harrison’s Phil Daniels-esque rap, while the soaring and storming “The Greatest Parade” brings to mind Black Market Music-era Placebo, and the closing piano ballad “Supermoon” sounds like a lost cut from either the Velvet Goldmine or Hedwig soundtracks. And other songs are reminiscent of the swirling shoegaze of Catherine Wheel, the chiming post-punk of pre-Joshua Tree U2, the '60s-meets-'90s college-rock psychedelia of Kula Shaker, the Charlatans, and Stone Temple Pilots’ Vatican Gift Shop, or pretty much every era of David Bowie. (Harrison wryly mentions that his stellar cover of “Life on Mars?,” which he recorded for Mike Garson’s virtual Bowie Celebration the same year that he started working on Idols, “gave me a little bit of legitimacy with fucking older rock cynical bastards, which was beautiful.”) However, despite all that, and despite the album’s title, Idols never sounds like an exercise in rockist nostalgia.

Harrison—who literally grew up in his family’s famous guitar shop, Music Ground, frequented by customers like Noel Gallagher and Johnny Marr—acknowledges that he wanted this album to be “a love letter to rock music,” because “everyone's been afraid of the ‘good chords.’ Like, fucking ‘Tiny Dancer.’ Fucking ‘The Chain.’ Fucking ABBA. Fucking Queen! Everyone's afraid of the good chords, because they seem to be old and cheesy and fucking done.” However, he quickly adds, “I think that's why rock's been so ‘dead’ for a while, because it's been a regurgitation; you go the Whisky every fucking Friday and see every Guns N' Roses wannabe band. And I was like, ‘Fuck that.’ You have to make it your own. You have to take it and say, ‘This is mine now. It's a new thing.’

“So, why did I call it Idols? Because your idols teach you—and then you let them go. We all take things from people and put them in our tummies and regurgitate a new individuality. That's the point,” Harrison says. “With this album, some people are like, ‘Is it an homage album to your idols?’ But no, it's more me telling them to fuck themselves. Like, ‘Thanks very much for that. I'll take it from here,’ just in terms of my own individuality.”

Back on the subject of how Idols is both an artistic and commercial risk, Harrison is well aware that even if rock ‘n’ roll isn’t dead, it’s not exactly the most popular genre right now. But he’s hoping to help change that, proclaiming, “I don't mind putting my head above the trenches and getting shot at first. I kind of relish it.” He has always been a polarizing figure, anyway, sparking ardent admiration from his superfans and equally strong vitriol from the detractors who have unfairly dismissed him as some Hot Topic-clad punk poser. “I'm just excited, and people don't like people who are excited. They don't like it. They feel like it's staged or something,” Harrison says. “But the thing is, I am such a purist, whether people believe it or not. I will die if I'm not telling the truth. I will die for this thing.”

The now seemingly superhumanly confident Harrison admits that he once “really questioned” why he elicited such extreme reactions, and that he let criticism affect him deeply. “I've always wanted people to love me,” he says softly. “I look back on myself when I'm 18 years old in interviews, and I'm like, ‘Fuck me, man. You're so confident, kid! You didn't give a fuck!’ Because when you make your first album, no one knows who you are, so you have to make it for yourself. And then a million opinions get brought in, and I really think I had a lot of shit that I didn't want to face. People make you aware of things that you didn't even know you were insecure about. You read things about yourself and you go down rabbit holes and become insecure about things that you didn't even know existed a week ago. And I was really struggling. I had to go on a real journey to get my fucking strength back. I started working out. I got sober for a bit. I started taking back things within my control.”

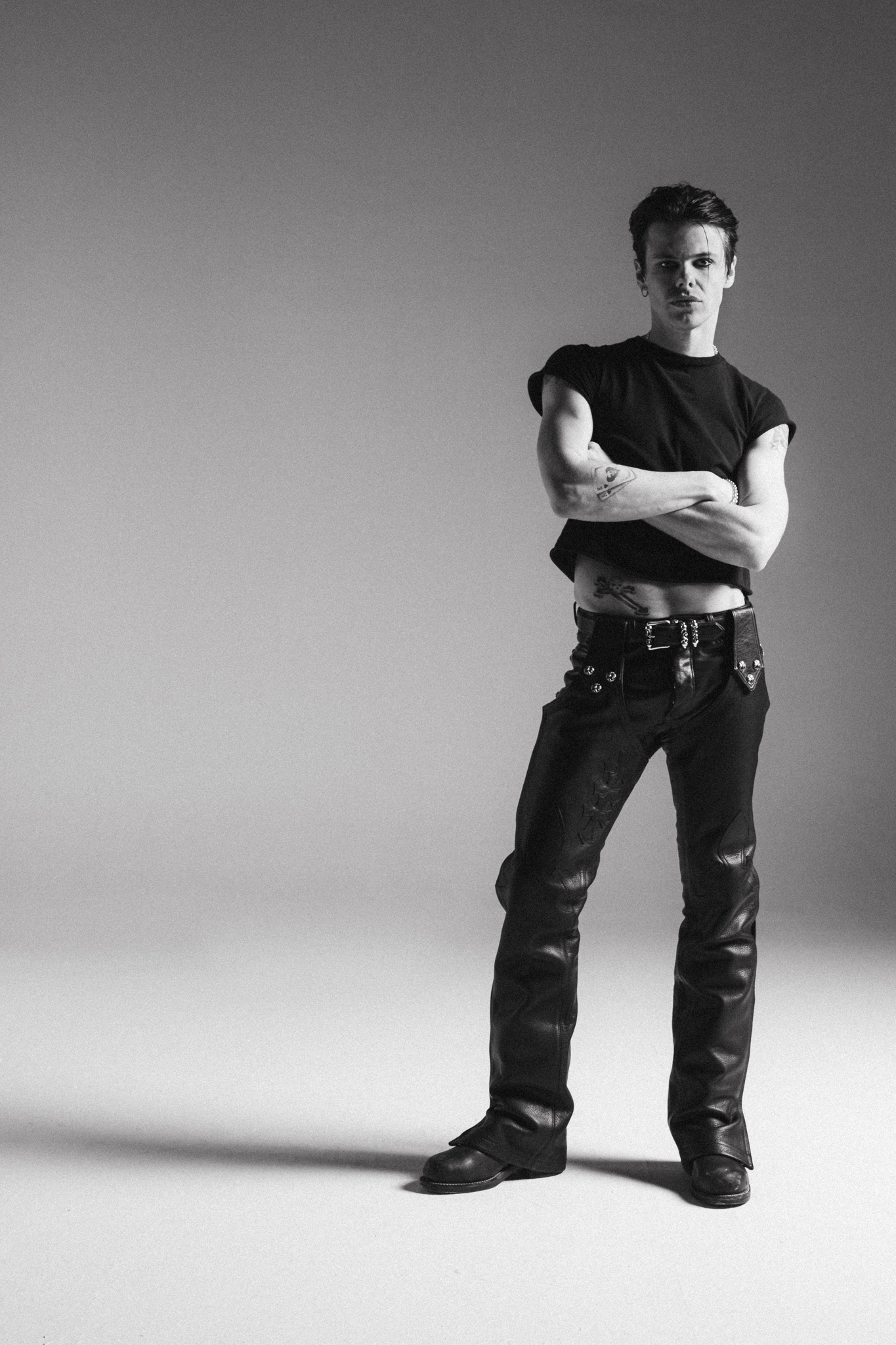

Harrison’s fitness glow-up—he’s joked that he is releasing Idols during his “shirt-off era”—has contributed to his newfound, hard-fought confidence. “I've always had issues in my body,” says Harrison, who has battled an eating disorder in the past. “I don’t know why I've always not liked myself, but I think a lot of things in the early days, when you're an 18- or 19-year-old kid and people can talk about your body in such a way, when you’re kind of formulating your personality, really made me insecure. A lot of people said shit about my body that was like, ‘Oh. Fuck.’ I was just wearing shit when I was fucking young, like a little skirt and shit, and people said things. It was weird to deal with. I didn't realize how hard it affected me until I had to address it all in my head. And with this album, I faced myself and said, ‘All right, Dom. How do you feel about this shit?’ I really found interest in feeling the pain. I thought it was an interesting thing to explore as an artist, to really feel the dark shit that I had repelled. With this album, I faced it. And it was terrifying as fuck.”

Idols’ string-laden confessional “Change” was the most painful song for Harrison to create, and therefore the most emblematic of his journey. “I was fully at a moment of I had to look myself in the mirror, and I remember crying my fucking eyes out when I was singing that,” he says. “It's so musically strange; it has no rhythm or no form or melody, and it just goes on this mad tangent. It was almost like an existential experience, because it just came out of me lyrically in that moment. I've never had an experience like that. I didn't think about it. I didn't write it. It was just fucking vomited out of me. And it's going, like, ‘Why the fuck are you walking with your head down? Where did you go? Where is this strong kid? Where did you go?’ And by the end of that statement, I'm like, ‘Boy, they fucking missed. They all fired, and they fucking missed. And you're still there.’ Everything I'd ever experienced, from being misunderstood as a kid, to having to justify my every fucking movement to everyone in the world, it all just kind of came out in that song.”

As mentioned, for every Yungblud hater there’s a Yungblud stan, but while Harrison is grateful for the “beautiful community that loves me”—his fanbase nicknamed the Black Hearts Club—he has always been uncomfortable with that sort of worship as well. “I fucking hated that mindset. Being called ‘voice of a generation’ and all that bullshit. I hated being put on a pedestal. I really do not like the pedestal. So, with this album, I wanted to explore the idea of idolism. This is actually the first record where I wasn't looking to anyone else for an answer, just looking inside myself. It is about fundamental self-reclamation and telling people that you've got to be the idol in your own life.”

Harrison realizes that not all of his followers will understand or accept what he’s trying to do on Idols, but he’s not bothered. “If you want consistency, I'm not going to give you that. I'm not going to make an album the same as the last one,” he states flatly. “This has become so much bigger than a kid in pink socks with a striped T-shirt on. That kid is not there anymore. Whether people like it or not, it is a different thing. So, I'm tired of holding back out of fear of not being liked. I'm tired of holding back out of fear of people turning in their nose. If people fucking don't like it, well, I can't help that.”

So far, Idols’ two singles have been very well-received, particularly in the U.S., where Yungblud (who has won or been nominated for multiple NME, Brit, and MTV Europe Music Awards across the pond) is still considered more of a rising star. “I really think America is going to get this album,” he says, freely admitting that “breaking America” has “been the dream, always. That's always a thing placed upon you as a British artist. I'd love to build a base here that gets bigger and bigger and bigger. The dream would actually be to sell out Madison Square Garden.” In the punk and indie worlds, it’s usually considered uncool to so audaciously and unabashedly express such lofty goals, but he finds that attitude “fucking tiring. I really feel like ambition is ridiculed a lot, especially in rock music, and I don't understand why. I just want to go out there and try my best at making something fucking huge. And I have the bollocks to say that.”

Idols is only the first step in what Harrison teases will be an ambitious “18-month journey,” which will include an Idols II sequel, out in October, that will be “darker, less heady, and less psychedelic—part one is the self-reclamation in the light, and part two is the downward spiral and the realization of mortality.” Harrison says he “didn't set out to write a double-album, but the well wasn't dry. When I'd finished the first part, the story developed, and I was like, ‘There's more to say. There's more to do.’” This journey will also include some other projects that he’s keeping under wraps for now (but promises will be “fucking cool”); a second year of his namesake BludFest Festival in Milton Keynes; and a U.S. tour that won’t stop at Madison Square Garden this time around, but will kick off in August at a historic Sunset Blvd. venue considerably larger than the Viper Room, the Hollywood Palladium. He hopes to perform Idols in its entirety on that tour, so along with his fitness regimen, he’s been taking vocal lessons for the first time in his life, in order to develop the stamina for these challenging gigs.

“I really wanted to sing on this record,” says Harrison. “I watched Billy Corgan on a podcast two years ago and he talked with my voice for like three minutes, and afterwards one of my best mates, Lewis Capaldi, was like, ‘Dom, just fucking sing!’ So, this album was the most ambitious vocally that I've ever been. It's fucking crazy and fucking hard to perform this album, because it's so fucking musical! I can't bullshit it. In the studio, I was exploring different parts of my voice, and it felt safe because there's no one around and you’re locked away in the middle of the country, and you can try and reach notes and fuck up until you find them. But then, when I finished the album, I was like, ‘Holy shit, these vocals are insane! How the fuck am I going to sing this every night?’ But now I really believe, with true, devout confidence, that I'm probably the best rock singer in the world at the moment—under 30, that is, because obviously a lot of fucking legends are still around—and that’s because I'm fucking going for it.”

Regarding being under 30, it’s not lost on Harrison that he’s releasing such a career-defining opus as Idols at 27, an age when so many rock idols’ careers were tragically cut short. And one of the album’s tracks, the triumphant anthem “Ghosts,” is specifically about grappling with a sense of his own mortality. “It’s the idea that I ain't going to be here forever. That's really what this album is about more than ever,” he says. “Even though it's such a cliché, that ‘27 Club,’ it does make you re-evaluate things. It’s like, ‘Oh, fuck. Would I be happy with what I left behind? Artistically, before this record, did I reach my potential?’

“And the answer was no. No way. But I feel like if this album was the last thing that I left behind, it would justify that itching I have to strive for greatness. Do I think I'm fully there yet? No. But I feel like I'm on my way. So, let’s go on a journey. Pack a fucking bag.”

Visit yungbludofficial.com.

Photos by Tom Pallant.