D. A. (Donn Alan) Pennebaker who died at age 94 of natural causes Aug. 1, 2019, on Long Island, New York is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of cinema verite filmmaking.

I had the honor of interviewing Pennebaker seven times this century for a few of my books, including Hollywood Shack Job: Rock Music In Film and On Your Screen and A Perfect Haze: The Illustrated History of the Monterey International Pop Festival.

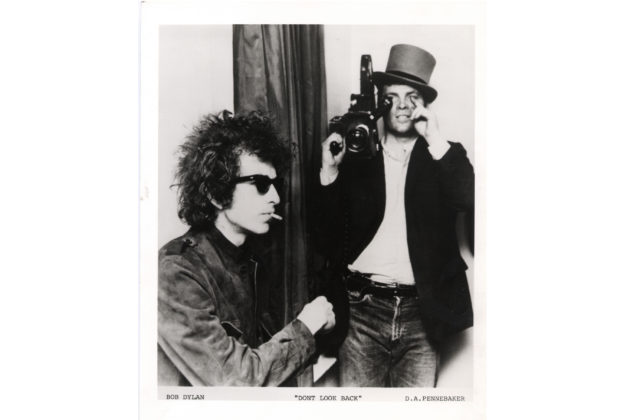

I also did stage lectures and movie analyses for Prof. David James' classes at the University of Southern California School of Cinema-Television's Cinematheque 108 series, about Oscar-winner D. A. Pennebaker. I examined his Bob Dylan Dont Look Back (1965) and David Bowie Ziggy and the Spiders From Mars (1973), documentaries. In 2016, Oxford University Press published Dr. James’ book Rock ‘N’ Film Cinema’s Dance with Popular Music.

Director Pennebaker is the recipient of numerous awards including lifetime achievement recognition—the Gotham Award, the Platinum Music Network Award, the John Cassavetes Award, as well as career awards from the International Documentary, Full Frame Documentary and Hot Doc Documentary festivals.

Pennebaker was given a Lifetime Achievement Award for Independent Feature Project at the Gotham Awards in 1992 and the John Cassavetes Award from The Denver International Film Festival in 1998.

In 2012, he received a Lifetime Achievement Academy Award.

Author, deejay, member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and former manager and record producer of the Rolling Stones from 1963-1967, Andrew Loog Oldham said in a 2017 email, “D.A. Pennebaker is an audiovisual Walt Whitman of our musical heritage.”

May 17, 2017, marked the 50th anniversary of the first-ever theatrical screening at the Paradisio Theater in San Francisco of Don't Look Back, Pennebaker’s documentary that explored Bob Dyan’s 1965 concert tour in England.

Dont Look Back stars Dylan and his manager Albert Grossman, along with appearances by Joan Baez, Bob Neuwirth, Donovan, Derroll Adams, Alan Price and Tito Berns. Uncredited cameos are from John Mayall, Tom Wilson, Terry Ellis, Jones Alk, Allen Ginsberg and Marianne Faithfull.

Impact and references from Dont Look Back can be found in the work of Jill Sobule, Mick Farren, Belle & Sebastian, Patti Smith, INXS and Weird Al Yankovic and hundreds of musicians and movie-makers who have viewed and used the flick as their filmic handbook.

In 1998, Dont Look Back was chosen for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

Pennebaker shot 20 hours of film of Bob Dylan in his last acoustic tour during the landmark UK ‘65 trek.

The film was done in a “cinema verite” style that he and his peers at Drew Associates introduced. It was a direct cinema technique and style that incorporated a fully portable 16mm synchronized camera and sound system.

Greater access to the subject was garnered by this unobtrusive method of filming that employed hand-held cameras and “fly on the wall” techniques that caught Dylan, concert performances and moments chronicling a radically conceived portrait of an American icon that influenced decades of verite behind-the-scenes documentaries that have followed his celluloid path.

After Dont Look Back premiered in May 1967 at the Presidio Theater venue in San Francisco, the movie was booked that September at the 34th Street East Theater in New York and in Los Angeles in nearby Hollywood for an extended engagement that ran for months at The Feliz Theater. Just a few miles from Fairfax High School, I went with a handful of students to see it that long-awaited first weekend.

“Los Feliz art house opening night,” volunteered documentarian Andrew Solt, co-producer and co-director of This is Elvis and co-producer and director of Imagine: John Lennon.

“Transfixed. Dylan on screen. Not stage. Docu verité window into a magical world—spellbinding moments, musical gems, beyond comprehension. Next day. Same time. Same same place. Back in line for another shot,” willingly confessed the head of SOFA Entertainment in 2017.

Jack Nitzsche, Denny Bruce and Neil Young were also there when Dont Look Back debuted. The following evening, Neil went back for a second viewing.

Dont Look Back played the underground cinema and art house movie circuit from 1967-1973 when Dylan wasn’t touring and off the road. So, the only Dylan people and music fans could see was on the big screen.

In December of 1967, director Murray Lerner’s Festival! was released which spotlighted live footage of Dylan from his performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

During 1968, host John Gilliland read an excerpt of an August 1967 Newsweek review of Dont Look Back on his Pop Chronicles Ballad in Plain D: Bob Dylan show that was broadcasted on Southern California radio station KRLA. He read, “It is really about fame and how it menaces art, about the press and how it categorizes, bowdlerizes, sterilizes, universalizes or conventionalizes an original like Dylan into something it can dimly understand.”

In 1968, Dont Look Back won Outstanding Film Of The Year at The London Film Festival. In 1968, Balantine Books published a transcript of the movie, with photographs.

“I saw Dont Look Back in a Los Angeles theatre—the Los Feliz,—just when it opened, in May 1967,” emailed Dr. James Cushing in 2017, an English and Literature Professor at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo and a KEBF-FM deejay.

“We must remember that, as far as I or anyone in my circle knew, Bob Dylan’s June 1966 motorcycle accident had left him either 1) dead, or 2) so permanently disfigured that he would never tour or record again.

“Like the Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits LP released that same season, Pennebaker's movie functioned within the context of the star’s disappearance; this movie was as close as you were ever going to get to seeing this brilliant-but-now-vanished legend in concert. And the movie kept functioning that way until early 1974 when the legend returned to the boards.

“The movie’s still astonishing, even if one’s seen it a hundred times. I show it on DVD to students and they identify with the young genius right away. When I watch the DVD myself, I’m always struck by Dylan’s youth and self-confidence, and by the permanent power of these songs as evocative works of art. That Pennebaker included the non-Dylan scene with Albert Grossman and Tito Burns in the office is a tribute to his courage and sense of realism. (Has there ever been a similar scene in any music documentary?)

“Having no friends to accompany me, I saw it with my very conservative father (born 1920, Marine Corps in WWII), who detested everything about it; his main comment, as I recall, was that ‘the whole movie was close ups of a bunch of really ugly-looking people!’

“That remark encapsulates the period’s ‘generation gap’ as well as anything I can remember. In terms of blending concert footage with behind-the-scenes intimacy, it remains the best ‘rockumentary’ movie ever,” Cushing declares.

D.A. (Donn Alan) Pennebaker was born on July 15, 1925 in Evanston, IL. He was educated at Yale and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

During 1953, Pennebaker made the movie Daybreak Express which reflected his love for Duke Ellington.

In 1959, Pennebaker, Richard Leacock and Albert Maysles joined Drew Associates, a group of filmmakers organized by Robert Drew and Time Inc., which was created to expand the use of film in journalism.

Drew Associates is where documentary editor and later producer, Charlotte Zwerin, encountered David and Albert Maysles. That trio would go on to do the monumental Rolling Stones’ tour documentary, Gimme Shelter.

Drew was a pioneer of direct cinema and a style that captured reality on film. They birthed the “Living Camera" series of documentaries and developed one of the truly portable 16mm synchronized camera and sound recording systems.

In 1964, Leacock-Pennebaker Films was formed. Pennebaker and crew shot two songs at a 1964 Lambert, Ross & Hendricks recording session at RCA Studios in New York. Within a month, Albert Grossman, Bob Dylan’s manager, visited their offices and suggested a documentary film on his client.

In 1973, Pennebaker lensed a concert by David Bowie called Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, currently on DVD with bonus features.

Over the last 50 years, along with partner Chris Hegedus who collaborated with him since 1976, Pennebaker imbued and shaped the formation of the documentary movie form.

In 2017, a Director-approved New Video/Docurama edition of Dont Look Back was released from Criterion.

It was a restored 4K digital transfer with newly restored monaural sound from the original quarter-inch magnetic masters presented uncompressed on Blu-ray. It contained audio commentary from 1999 which featured Pennebaker and tour manager Bob Neuwirth, 65 Revisited, a 2006 documentary by Pennebaker, an audio excerpt from a 2000 interview with Bob Dylan for the documentary No Direction Home, previously unseen outtakes from Dont Look Back, a new documentary about the evolution of Pennebaker’s filming style, a conversation between Pennebaker and Neuwirth about their work together, snapshots from the tour, plus a new interview with Patti Smith, along with a conversation between music critic Greil Marcus and Pennebaker from 2010.

There is also an alternate version of the film’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” cue card sequence, five audio recordings of Dylan songs not used in the film trailer and a booklet featuring an essay by critic and poet Robert Polito.

There is a single DVD release of Bob Dylan: Dont Look Back. This format offers consumers the new digitally-remastered version from the 65 Tour Deluxe Edition minus the two vintage collectible photo-laden books and second disc.

“Originally when I made the film Dont Look Back I wanted to be sure it wasn’t about music that it was about Dylan,” remarked Pennebaker in a late 2004 interview with me.

“What you see now that maybe it should have been more about music. And Neuwirth always thought that and cautioned me, ‘Look out.’ But in a way, Dylan was what everybody wanted to know about. And the music they could get on the records.

“You had to see the music performed. The film took possession of me. I was in the zone for Dont Look Back. Maybe Dylan was in the zone.

“I knew that once I got started I just had to roll and not plan anything. I didn’t try and be smart about anything. I never asked him a question. I didn’t want to know anything. The whole thing was a walking tour, like walking up a mountain. Your feet take you there and when you get off the train you made sure you had a new roll of film there.”

In December 2006, I talked to Pennebaker over the telephone from his office in New York City and he discussed the Dont Look Back bonus footage and complete “outtake” sequences that constitute an hour on the disc produced with his son Frazer.

“I started to look at the outtakes as ‘evidence’ of something new. As I looked at them I thought, ‘those things look so great in the black and white you can put them upside down.’ The fact is that the black and white looked kind of marvelous in its simplicity. The outtakes are like old girlfriends. And you have a kind of nice memory but when you see them they’re grannies, ya know. It’s hard to remember what it was that struck you about them at the time. A film that you do, like Daybreak, one of my earlier films, I see it now almost the way I see someone else’s film. The uncut performances had an effect on me,” Pennebaker revealed.

“When I did Dont Look Back I was sure I knew what I was doing. I edited it in 2 or 3 weeks. It was like walking across the Peruvian Andes on a rope and I had to move fast and not take time to think about it.

“With a viewer. No Avids then. You move faster and it’s closer to what the Avid will do. It’s much faster than a Steenbeck [flatbed editing system]. A little screen and a light in there and you take a synchronizer which you draw your tape and your film through, and on the synchronizer we’d put a little head and we built these magnetic pickups and they fed in to a little squeak box or into your earphones so that when you pulled it through, and if you had a 22 frame pull up you heard the sound that went with the picture that was in the actual viewer and you could go very fast. And for me moving fast through a film you are editing is really important. I don’t know why exactly. I hate to dwell on stuff because you start to make it pretty.

“Well, when I looked at the stuff now, the complete songs, I realized, first of all, the things that worked really were the love songs. Not the protest songs. The songs when you hear ‘em now complete, from beginning to end, what strikes me is the guy, at that time, the music was everything. The music accounted for everything he had to offer in a way,” marveled D.A.

“There was no myth or legend yet. It was so incredible. Dylan had such an amazing kind of mercurial sense that translated to people. And when I see these full songs I think, ‘shit, I made the wrong film.’ I mean, it really hit me like that. And I thought, ‘No you can’t just listen like that,’ because a lot of something went into it and it worked.”

Pennebaker explained why Dont Look Back has kept finding a new audience.

“It kind of makes you feel like you did something right once. (laughs) It doesn’t make me feel bad at all. It interests me that people have the same fascination with Dylan that a lot of people had without being able to quite understand it. I know how I feel about Byron. I think he’s an important person in our culture and why everything is derived from what Byron set forth. Dylan, I think in a hundred years, will have some kind of same quality that people will look back and say, ‘oh that’s where that came from.’ So it interests me now that people see it in the movie that when it was made it was all a guess.”

In another phone conversation I had with Pennebaker a few years ago, I asked him about displaying Dont Look Back on big movie house screens in addition to the DVD format. He once even released a laserdisc version.

“I think it’s kind of a Zen thing,” suggested Pennebaker. “Your mind is able to deal with it on any size. Big is nice, especially if you have bad eyesight, big is terrific in a theater. And we’ve made a 35mm blow-up of that. I love seeing it in 35mm and we show it at some festivals and it looked great.”

In 2004, I interviewed D.A. Pennebaker at the Sunset Marquis Hotel in West Hollywood for Goldmine magazine. Portions of our conversation were then published in my book Hollywood Shack Job: Rock Music in Film and on Your Screen.

Q: Do you remember the first time you screened Dont Look Back for Dylan?

A: Yeah. I didn’t know what was going to happen. But I knew that room was full of people that I hated. I didn’t know where they came from or where they went. Two nights. At the end of the first evening, Dylan said, "We’re gonna do the same thing tomorrow." It was a terrible screening anyway. It was out of synch and I was really depressed. And then we were going to figure out how to change it, or whatever he was going to do. And then the next night, ya know-bang! "It’s fine. That’s it." He had an empty pad. So I thought well this guy is an amazing person and I was really not only lucky to be able to film but to have his mind contemplating its release.

Q: Dylan viewed the Dont Look Back DVD.

A: Yeah. We’re partners. We deal with Jeff (Rosen) in his office all the time. But Dylan came over and he looked at some footage on the DVD and said at one point, "How did you get that great sound?" I said, “Well Bob, you’re gonna be surprised at this. It’s all mono." "Mono…I gotta tell the guys down at Sony about this."

Q What about Dylan as a camera subject?

A: Well…he is what he is. He’s different in the afternoons than he is in the mornings. So you’re never sure who you are getting. He’s the twins. I think he’s a person who understood theater very well. Even though he was very naive about a lot of things. You’d often would talk to him about somebody and he wouldn’t know who you were talking about, "Jesus. He’s gotta know who this person is." Then, other people, he would know a lot about. It amazed me where he got his kind of primal information because it was always right on the nose. It didn’t seem like he’d been through a lot of education. He seemed to have got it from the streets.

Q: You had a prestigious track record before Dont Look Back. I remember films like David shot at the Synanon House in 1962, won awards at The Boston International Film Festival in 1962, and Daybreak Express was honored at the Mannheim Film Festival in 1964.

“I’m amazed to know that you couldn’t find a distributor for Dont Look Back when it was done. And that you and Leacock were hawking a finished print about a subject who in summer of 1965 had charted in the AM radio top 40 with “Like A Rolling Stone,” and had been critically hailed for a few years. And you couldn’t convince Dylan’s label Columbia to help finance the production. Finally, you secured an opening in San Francisco in May 1967, and then New York and Los Angeles.

A: There’s always a delay between the people at the gates and the public. I still have the letter of rejection from a guy at Warner 7 Arts. It’s very funny. Finally, he took his daughter to see it in San Francisco and at the end of the letter he said, ‘The funny thing was my daughter really liked it." It opened at The Presidio in San Francisco. I was desperate. Because I showed it to a lot of people and took it out to places like Milwaukee and showed it at civic centers and the place would be filled with people who afterward would come up with tears in their eyes. And I said to myself, there’s an audience. Why can’t I get the local theater to run it? They wouldn’t even look at it. Theater owners don’t look at films. Usually, they go by their distributors. So I was stuck.

"Then this guy walked in one day and said, "I’m told you have this film about this singer." He didn’t know who Dylan was. "I represent a bunch of theaters out in the West called Art Theater Guild and we run mostly…" I think he meant porno films and was looking to clean up his act. So I showed it to him and he said, "Ya know, it’s exactly what I’m looking for. It looks like a porno film but it’s not. I’ll open it in The Presidio." I didn’t know where The Presidio was at all. Somebody later told me "that’s a wild porno house out in San Francisco!” Ricky (Leacock) and I came up after Monterey and I was so pleased we had gotten it in a theater finally that I didn’t want to tell Ricky what it was.

"We stayed over in North Beach and the next day with a very heavy heart I said "Let’s go see how our movie is playing." It had played two or three weeks there. So we went to the theater and I said to Ricky, "Watch this." And Ricky was very nervous about money in general. He saw the big long line outside and thought "we’re just making money for the theater and they’re never going to pay us." So I said, "Ricky, watch." So I went up to the place, this old falling apart porno house and said to the guy, "Would you give me some money?" "How much?" And I said "$500.00." And he made me sign a note and Leacock just died.

"That was a great moment for the two of us. We totally recognized that we could make movies. We didn’t have a 35mm print. San Francisco had my answer print. It played in San Francisco for almost a year in 16mm. Then New York came around came four months later when it showed at the 34th Street East. The company didn’t even have to run ads."

Q: Haskell Wexler, who in the late ‘60s directed Medium Cool, told me you used modified portable Auricon camera equipment for Dont Look Back, and you let him borrow that camera for some of his earlier shoots like The March On Washington.

A: Yes, but on Dont Look Back, the camera I had was the best one I made yet. I used Angenieux lenses. He was a Frenchman and he’s dead now. He invented the zoom lens. A marvelous guy. He had this lens for studio cameras where he had this long finder ‘cause you had it on a tripod, right, and you had to stand by and look. And I told him "that’s not going to work for me." And he said, "Why not?" And I showed him my camera on my shoulder and my eye was right there at the thing. And I told him what I wanted and he said, “Oh boy. That is really hard and I can hardly wait." And he made me one. He made me one.

Q: What about film stock?

A: I think I was using Tri-X and pushing it (increasing film speed). And I did it through Humphries in London ‘cause they were a really good lab and they did, I think, a pretty good job and we wanted it right away. I had no lights. We used available lights. The people I showed it to at United Artists wished I had used more lights. They saw it as a ratty, underexposed film, you see, because they weren’t thinking that that was Dylan’s film, that’s what Dylan should make. They saw it in terms of Katherine Hepburn. So it lacked.

Q: Were there any advantages in shooting a film in black and white as opposed to color?

A: Well, it’s different. You put your mind into that and then it sits there and you don’t have to think anymore. What you want to do is to get so that when you’re shooting you don’t have to think. You don’t have to think about "should I be closer?" As soon as you think in those things, the film disappears. You want your feet to take you where you should be. You want the camera to film what you want it to film. You don’t want anything to happen so you won’t have to think about it. And then it can happen in some part of your brain that’s non-word-oriented, or something. I don’t know. But I get in that camera and I don’t want to come out.

Q: With the DVD release of Dont Look Back, it seems more than ever that Dont Look Back keeps finding a new audience and lots of kids are discovering it.

A: Yes. It kind of makes you feel like you did something right once. (laughs). It doesn’t make me feel bad at all. It interests me that people have the same fascination with Dylan that a lot of people had without being able to quite understand it. I know how I feel about Byron. I think he’s an important person in our culture and why everything is derived from what Byron set forth. Dylan, I think in a hundred years, will have some kind of same quality that people will look back and say, "oh that’s where that came from." So it interests me now that people see it in the movie that when it was made it was all a guess.

Q: The Dont Look Back title is an ode to baseball player Satchel Paige.

A. I always felt that was right. What he was saying made perfect sense for anybody who was doing something really well they had to be careful not to look back and see how well they were doing it. They had to keep going and couldn’t become archivists of their own material.

Q: Was there a tough feeling of just letting go when Dont Look Back began? I mean you didn’t storyboard anything or work off a script.

A: There is because originally it began in the dressing room where he says "you start off standing." Right? I said, "That’s a cute way to start and I’ll put a little title in and put my name in." That’s all I need to do. And the first time I looked at I thought, "Shit, it didn’t work maybe because you don’t know who the hell this guy is." And he’s being cute in the dressing room but why should you care? And then we had that thing we shot that was Dylan’s idea to shoot the cue card scene for the opening with "Subterranean Homesick Blues." So I stuck that on the front and that did it. So you just do it and when you’re in that zone, whatever you do will probably work. And I had a never-before-seen version of "Subterranean Homesick Blues" that we have on the DVD.

Q: Sound is very important in Don’t Look Back. Jones Alk who did your sound in the film is a thread throughout the movie and she was palming and carrying a microphone. And the movie is dialogue-driven since I know you didn’t’ want to make a concert movie. And no lighting and no boom mikes. Jones Alk wasn’t intrusive in the movie.

A: I don’t like booms. You look peculiar with a boom. There are many ways of getting the sound. In Dont Look Back you never see a mike in Jones Alk’s hand and never know she was doing sound. She’s just watching what is going on. She was using two Sennheiser microphones and one was a directional (“shotgun mike”) in her lap.

“I never told her what to do. From the beginning. She was Dylan’s friend. She managed to always keep it out of the camera. She’d watch me just enough so I’d knew how to contact her and didn’t have to think about it. I don’t think she had ever done sound before in her life. I have no idea. She was perfect. I’ve never found a better sound person, ever. That’s what I mean by being in the zone. I hadn’t met her before I got to London. Dylan brought in Howard Alk, but I didn’t want to have another camera.

“I didn’t want to get in to ‘shooting the concerts.’ I thought, ‘Gee…if I have a second camera then we’ll have to have a lot of film for the second camera because he’s not going want to stop shooting.’ And I was ready to shoot little bits of songs ‘cause we recorded every concert. So I knew I had soundboard and it was all Mono on a Nagra.

“In 1965 I would look through my lenses and the words would drop on the music. I was just amazed at how anybody could produce that kind of electricity. To me that was what art was about."

Q: You mention in the DVD narrative that all films have a center. And Dont Look Back has a center. Does a film arrive and then wind down?

A: Yes. Absolutely. I never know when we are shooting but in editing, I find it out later. Shooting is just summer camp. When I saw Dont Look Back, I knew exactly what was the center and it changed the whole ending of the film. And it’s when he says ‘Don’t Think Twice It’s All Right,’ and you go to the train. That’s the end of that part and then from then on, it’s different in my head. Now nobody else may see it that way and I don’t want to say this or indicate in any way ‘cause that film is as much anybody watching it as it is mine and that’s its strength I think.

Q: I was taken by the tension, anticipation of the crowds and fans and the hysteria around Dylan that you caught on film.

A: I caught that in the audience. I think that it will take 50 or 100 years to really digest Dylan. He’s like John Brown. He’s out there singing a song and he’s gonna sing it until he drops. And it’s like he doesn’t have to understand it completely. That’s what he’s going to do. The concerts now are like transfigurations but they’re interesting because you can’t sit on a talent like that whatever you do is going to be interesting.

Q: You’ve seen Dont Look Back on the big screen in a movie theater. You’ve released it on home video for the small television screen format. Now DVD.

A: When DVDs came along, I was really intrigued. I see them as a whole new thing. They’re like magazines. And what the people were doing was interviewing the director which is only mildly interesting at best and usually boring. You could get people of talent, which is what magazines do to come in and bring it to life and we kind of wanted to find out first of all how it works. So, we didn’t want to get into interviews and I said to Bob Neuwirth, "Why don’t you and I just lock ourselves in the studio and we’ll talk for a couple of hours." No production meetings. We each had a microphone. Kim Hendrickson [from Criterion] was the person who kind of produced it with us because she understood that we didn’t want to get into any of the jazz of interviewing.

Q: The Dont Look Back DVD reminded me how much Dylan’s friend and road manager Bob Neuwirth was involved with you in the film. You talk a little about it in the new DVD commentary.

A: He made all kinds of shit happen. I didn’t have to ask him or talk to him about anything. We never talked about it at all. He understood immediately how the thing worked and made it work better. And Dylan understood a little bit but he didn’t understand how naked he’d appeared. That was the thing that surprised him. Neuwirth knew from the start how it was gonna be. I don’t know why. He’s an artist, and he shot some films himself. That amazed me. Neuwirth’s role in that film was crucial and that’s why I wanted him to be the one I talked to.

Q: After so many decades, viewers are still talking about the scene of manager Albert Grossman and agent Tito Burns captured in a business negotiation.

A: You could never have that scene today. Management wouldn’t allow it. One time a groupie came up to a table where I was sitting at The Kettle Of Fish in New York with Albert and this girl said to Albert, "I can’t believe I saw you in that movie and you looked like some sort of bandit from the swamps or something." And I said, "Albert, I feel badly if I ruined your reputation in the village." "Don’t think about it," he said. "It’s exactly what it should be."

“I thought that’s the way to deal with it. Take it as it wasn’t going to be his lifetime put down. Tito Burns and I talked years ago and he liked himself on screen."

Q: When you shot Dylan singing “Hattie Carroll” in a Dont Look Back performance you had an interesting camera angle.

A: In your face from the underside of the floorboards. I was lying on the floor and the only way to keep it steady was to lie down. I started figuring it out from one concert to another and would shoot a little bit. I never saw anything until I got back to New York. You look through the camera and you kind of know what you got and you think about it. "Where should that go?" I didn’t know what to think. Your feet take you there and you go.

Q: After countless viewings and question and answer sessions after screenings, and feedback from a few different generations, what have been some of the reactions that have been consistent over the years?

A: They love the science student. (Terry Ellis, later co-founder of Chrysalis Records). Somebody just interviewed him last week for a film they are making about me and Chris and there he was saying it’s the funniest thing in the world to have been in a movie when he was just trying to get a free ticket to get in. It was all really just off the wall. People discover things like The High Sheriff’s Lady introducing her sons with the same names. Things like that.

“People respond to things where you don’t rub it in too hard. And earlier when I was working with Drew-Time Life, Inc. we were always narrating saying ‘now look at this,’ ‘now listen to this.’ With Dont Look Back, there was a way to make films in the real world and not upset it.

“With Dont Look Back it was more like a magazine just to make sure that it was what you did in a magazine. Make sure everybody got it. And I liked the idea of a lot of people not getting it. And the people who did get it knowing there were people around them didn’t get it. I like that whole chemistry of people figuring out where they are in terms of what they get at that time. They may go back and see the film another time and get a whole other thing.

Q: Travel was a big thing in Dont Look Back. Taxis, cars and trains. Movement in general.

A: Yes. That’s what we did. I had shot transportation and car shots before. I think it’s like when people are watching television when they are driving cars, or driving in cars they become more absolute in some ways. They become realer. I like the information they give in those situations. So it’s a good place to get people especially if you want them reflective. They feel in charge of something and they don’t mind letting you in.

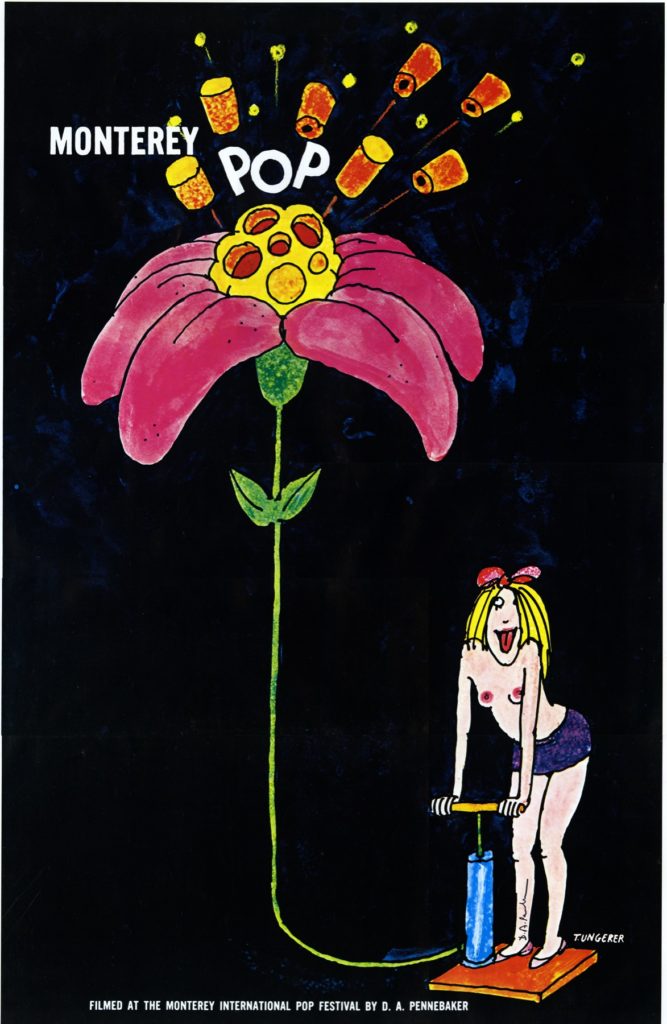

Q: What did you learn from the process of doing Dont Look Back and filming Eat The Document about Dylan’s 1966 your that you applied to Monterey Pop? in 1967?

A: I learned to trust myself. Before I wasn’t sure I could make movies and it wasn’t until Jane that I knew I could do it. Then I felt like I just shot five 50 cent pieces. In Dont Look Back it was a whole one thing and I did it almost totally by myself. I had Jones Alk doing sound and I had Bob Van Dyke doing the concerts, and Bob was doing the sound when I was doing Albert and Tito Burns. He was known for his late nights and some drinking, and he fell asleep on the corner of the desk. I have a picture of him holding the microphone up all the time and I didn’t want to wake him up.

“It’s like the tennis player, Chris Everett Lloyd. I adore her and I want to make a film of her. I love that she’s in the zone. She was the first person I ever heard use the term, ‘in the zone.’ I understood exactly. When you’re in the zone you can not make a mistake. You can jump out the window and land soft.

“I was in the zone for Dont Look Back. Maybe Dylan was in the zone. I knew that once I got started I just had to roll and not plan anything. I didn’t try and be smart about anything. I never asked him a question. I didn’t want to know anything. I just wanted to get inside that camera and not come out. For me, that’s in the zone and I felt like Chris Everett Lloyd. The feeling that you are God.

Q: Monterey Pop is out on home video, and on a DVD. I know when you did the movie you made a conscious decision not to really do interviews for it?

A: Interviews didn’t interest me and I had access to do it. I didn’t want to take the time. I wanted everybody to concentrate on music. Well remember the guys I had filming for me there, except for Ricky (Leacock), he was the only other camera, they were all beginners. And I wanted them as I put them in pivotal positions ‘cause they could be with the music. They served the music and that was the thing. And I didn’t want them to think about anything except getting film to match that music.

Q: How did the genesis of the Monterey Pop even begin?

A: Bob Rafelson (The Monkees TV show) called me up and he said ‘would you like to do a film of a concert in California?’ And I thought about it and I had just seen Bruce Brown’s Endless Summer, which is not about surfing at all, but all about California. Every kid out of high school the one thing they wanted to do was get to California, and Endless Summer didn’t hurt.

I saw Rafelson once, maybe, but he was never involved. It was always Lou Adler and John Phillips that I dealt with. And we flew up with Cass (Elliot) to see the place and I looked at it and it was this tiny place. I had no idea what was going to happen there. I had never seen a music festival at all. Not even Newport, so I didn’t know what to expect. It had a really nice feeling to it and I loved Monterey and it’s a lovely place. And I sort of thought, ‘well these guys know what they are doing.’

John and Lou. John was a total genius. He was part Indian and had a mystical view on everything he did. And he hadn’t been playing music for long. The Journeymen a couple of years before The Mamas & Papas. Everything he was doing was like he’d been touched and as long as the spell was there it just flowed out of him. I loved John. He was marvelous. Lou knew what he was doing and I knew he was a real good sound mixer ‘cause I had listened to some of the stuff he had done but I knew they were hatching a real interesting game. Which was from the beginning get rid of the money. That was the big thing. Get rid of the money. And I could see that that was gonna make it work. It was a very Zen thing but

I can see that, and later I saw what happened at Woodstock, and I really didn’t want to get involved with that at all. One of the producers of Woodstock saw the film “Monterey Pop” and wanted to do a festival.

Q: I dug The Lost Monterey Pop performances I’ve seen from your original shoot. The Association, Paul Butterfield, The Electric Flag, and Laura Nyro. The music informs your film.

A: She called me up about a year before she died and wanted me to work with her on a music video.

Q: And the music sounded so good. I’m talking sonically, the official released version and the unreleased footage.

A: Well, we had Brian Wilson’s tape recorders that was one thing that made it possible. Those two eight tracks made it possible and Lou and John mixed that thing in John’s house while I sat there and listened to it and they did a fantastic mix. They were really good at doing mixes.

Q: Jimi Hendrix really connected with the Monterey audience and you got him on film. And Otis Redding’s performance. In 1986 you released his complete set at Monterey Pop, Shake-Otis at Monterey.

A: We had no idea about Hendrix going in. John had said, ‘Listen, this guy will kill you. He sets himself on fire.’ And he comes out and he’s chewing on his flat pick. I thought he was chewing gum, and I thought, ‘this is blues?’ I mean, I didn’t know what to expect. We had thought we would save film a little bit and shoot one song for every group. So we had this lamp with a little red light, and Neuwirth, I and John Cooke were gonna figure out what songs to do and in the end, Neuwirth kind of mostly figured it out, he was like the music director. And when Hendrix came on, I think the light was on for the first song I don’t why, but I remember that that light went on very soon and never went off for all the Hendrix thing and everybody shot everything. They had film for it.

Otis Redding was stunning. It’s a great film, almost a perfect film. He had a pretty good band, I was editing, or re-editing the section of his for Monterey Pop in late ’67 and changed the film a little bit when he went in to the lake and I remember that’s when I got in to all that stuff of doing things with the lights and I know at the time I felt, ‘ Gee. What am I doing? This is crazy.’ But I left it that way because I felt so bad that he kind of died on us and that made me sad. So it was the only thing I could do to mark that was to edit that way. In editing Monterey Pop I had my first Steenbeck.

Q: Did it make editing things quicker?

A: No, it was a little slower but I could hear the music really well. And I was making edits in the music sometimes. I’ve edited chunks out of that you don’t know are missing but I would normally never done it on a viewer or in my old editing bay.

I knew when I saw Ravi Shankar we would have to end with that. I remember sitting down at Max’s Kansas City and I wrote out a little thing on the back of a menu of what I thought the order of the music would be and you know it was very close to what ended up being. The only thing I pulled out were Butter (Butterfield) and The Electric Flag for very peculiar reasons. But the fact is that I almost knew going in without even thinking about it that it had to build from Canned Heat to Simon & Garfunkel to whatever it was, it had to be a history of popular music in some weird way that I didn’t ever have to explain to anybody ‘cause I had John’s music as a narration for the whole film so that just covered me.

“I think of these films like Monterey much more as if they were plays on a stage. And every play has to build to some sort of climax. Something it was all worth sitting there for. And that’s how you decide what comes next. And there was no dialogue. There was music talking to people. It starts with Canned Heat, like the first time you walked into a room with your older family members and you heard music that was a little beyond you that said, ‘Come on and try it.’ It starts with that and it works its way through the most amazing music. I was always sorry about editing out the Electric Flag,. Not that it was bad. It just didn’t fit.

Q: This decade you received a Lifetime Achievement Oscar for six decades of nonfiction filmmaking. The first documentary filmmaker to be given such an award. What are your feelings about being given an Oscar?

A: It’s a little complicated. It’s like being given the champion pilot’s award when you don’t fly. I mean, I never thought the Oscars were a waste of time or anything. They helped a lot of industry and people who are actors and probably helped get a lot of films get seen that otherwise might have gone awry. Although the process of distributing films is so huge. It’s like aspirins or something. There must be thousands of theaters waiting to hear what Paramount has this week to give them. It’s in place.

Q: The Oscar people and the public in large, missed your 1955-1965 life as a documentarian.

A: The documentary, when I quit life, was a harsh moment. Because that was my salary. And I had a child by then and I had to figure out that it wasn’t gonna work for me but I had to leave. So for the next 2 or 3 years, Ricky (Leacock) and I made films that we couldn’t distribute but they were some of the most wonderful films.

Q: Here you are in the late 1950s and television really started to look like a potential option for your work.

A: Ricky thought that television would be our marketplace. And the fact is, they didn’t even want to answer the phone. They were busy creating their own kingdom. They didn’t need outsiders. People who didn’t walk the halls in the morning weren’t part of them.

Q: What has happened in the last decade or two with more film festivals and more films schools. Why?

A: I think it’s like the rise of the electric train. I think nobody at the beginning of the century had any thought that a child would want an electric train. When Lionel or who ever invented it, when they came out with something that resembled the real world and in a very artistic way, it was really well done. He trains were not realistic exactly, but they were kind of beautifully crafted and all the scenery. So a person could create a whole kind of thing just because they existed. And so everybody got one for Christmas. Well, I think that the making of films by yourself, as opposed to going to a movie theater and seeing what somebody else has done. The idea of making your own is a contagious notion. It isn’t just a home movie. You’re getting an audience of people, who in a way pay to see how good you are. And it’s a shootout.

It’s like when people went to Revolver, Arkansas in the heyday of the cowboy to shoot it out with the local sheriff to see how good they were. You sort of ended up throwing silver dollars in the air and hitting them if you were any good. By shooting from the hip. In other words, it became a whole thing. A process that had its artistic and its spiritual aspects that people hadn’t planned on. But there they were.

So I notice when I go to festivals every show is sold out. Why is this? Why are people so fascinated to see documentaries? Well, at first I thought they were getting a kind of news that they didn’t get from theatrical films and that they certainly didn’t get from television. Because television limited itself to the news that promoted them. But now I’m not so sure. I think it’s become the electric train. And they want to see it. And they want to see it run. And it’s different from the movies they pay to see and craftsmanship on Hollywood Films.

I think it’s more than just the news, but a lot of documentaries address the news and the problem I have with most of them, is the theater is lost. These films have that quality, a kind of news event that you’re gonna find out about. But the theater is missing. And I must say I always think of my films when I’m doing them as plays. Because the playwright had the same problem we do. He had to get a lot of people on stage that had never been seen before. From the very beginning, he had to give you an insight into what was going to happen, what the play was about, why you were there, what was important about it. That was done in different ways. Shaw was good at it.

“Now the problem with the films that are made is that they find some situation that needs redressing and so they go and interview people what happened and they tell the story but they tell it as it what you hear had happened. Robert Flaterty was my hero, and in his late ‘40s, he had this person, Nanuck, and decided to make a film about him. A film about a friend.

Q: It seems you always knew it was about removal of ego as a director and cameraman or filmmaker.

A: You know where I think it arose, I grew up in Chicago. And when I was there, Chicago was changing in a musical way that nobody understood. That is a lot of musicians from New Orleans, Kansas City, St. Louis were coming to Chicago because the money was there. The criminals owned all the clubs and so they had the money. And talent always goes for the money. Sometimes they pretend they don.t but in the end, they have to. They don’t have any long-range assistance. All they are is as long as people want to hear them and they’re gone.

Q: And you subsequently made many music films and documentaries. Why has music informed a lot of your work over the last half-century?

A: The fact is I learned about jazz from records. 78 RPMs. Not hearing anybody play it. I never saw a live thing in Chicago in my whole life. But the record was interesting. It did a couple of things. It created a time limit. No matter how great your ideas were they had to be contained. And containing ideas musically with artistic talent meant you had to shape it in some way that people would follow it. And you wouldn’t them. And you started slow or fast but you moved in an orbit and then you ended it. And some worked better than others. But when they worked the whole concept of condensing a storyline and having it starting out with people who really weren’t sure. You might have had some music written for people. But basically, jazz musicians never paid much attention to it. So what happened was you began something that you knew kind of where you wanted to get to. A quality, a ring, or a tune, and everybody worked on that and figured it while you were playing. The thing happened while it was being played. What you did when you heard the record you witnessed how that came out. And that was kind of exciting. The improvisational aspect as well.

Harvey Kubernik is a producer and consultant on music and pop culture documentaries. Kubernik is an award-winning author of 15 books. His literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018.

Kubernik’s The Doors: Summer's Gone has been nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections Awards for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research.

During November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz.

Harvey Kubernik’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown, that initially was published in 1995 in Goldmine and HITS magazines, is included in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett to be published in 2019 by Oxford University Press.

This century, Kubernik penned the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century.

In November 2006, Kubernik was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.