Taking songs from concept to reality and capturing them for others to hear is a calling for many professional musicians. As recording technology continues to advance and becomes more readily accessible, artists are finding it possible to build spaces within their homes to help them produce the sounds they desire at moments of inspiration. Musicians who have perfected the art of embracing in-the-moment ingenuity take readers behind the scenes into their creative quarters to provide insight into how they transform snippets of songs into extraordinary compositions that resonate beyond those walls.

Excerpts and photos from the forthcoming book WIRED v2.0 are included in this article.

Phantogram

Sarah Barthel and Josh Carter

Phantogram’s ability to create bombastic, anthemic music that leans into ethereal melodies and ferocious beats has earned them respect from some of the industry’s most popular and prolific artists—Run the Jewels, Miley Cyrus, Queens of the Stone Age, Big Boi, Kings of Leon, the list goes on. Innovators of modern triphop electro-rock, Sarah Barthel and Josh Carter, explain how they produce those subversive, cinematic sounds from their L.A.-based music room.

When did you decide to have your own creative space and how did you approach putting it together? Did you have ideas about elements that were “must-haves” for it?

We’ve wanted to have our own creative space since we moved to L.A. almost 10 years ago. We’ve had places in the past that friends and family members have let us set up and record in. Our first album was created in a makeshift studio in Josh’s parents’ barn (Harmony Lodge). We’ve also had smaller “bedroom” set ups when we lived in Brooklyn, which often did the trick —at least for recording demos. As far as gear, we wanted to have our go-tos, like samplers, drum machines, and analogue synths. We’ve upgraded to “nicer” pieces as well. We bought some great microphones for recording live drums, a great microphone for vocals, and solid preamps and outboard gear. We also put in a [beautiful] upright piano.

How would you describe the creative process you undertake while working?

Our creative process in the studio is never the same. It could start from us jamming on guitars, synths, or the piano, but also by making a beat or [creating] simple rhythm patterns and then freestyling vocal ideas. Sometimes we will set up some microphones and work in Logic, or even record a voice memo on an iPhone. We are constantly messing with different [sonic] textures of guitars or synths and other pieces of random gear and percussion. After a lot of experimentation, we decide what’s needed or what will make a song sound more interesting to us. We will add and subtract elements until we get the desired outcome.

Are there any new recording techniques or ways of capturing sounds that you are developing?

Because we experiment so often, we’ve learned new recording techniques by messing around with different mic placements and different microphone models, including very inexpensive “bad” mics. Sometimes we will also take a traditional approach to capturing guitars, pianos, etc. to get a desired sound that is tried and true.

Is there what you might consider a pivotal moment or a turning point in how you both approach the songwriting and creative process?

Not sure about a particular moment, but some of the coolest sounds we’ve gotten have been from setting up multiple mics and just jamming or working out ideas. After that, we go back and listen and find parts that sound interesting and build from there, or sometimes sample or make a loop out of a happy accident.

How do you approach creating the sonic atmospheres often found in your music? For example, how do you decide where to place the vocals in the mix?

Constant experimentation.

Are there times you changed a song or sound while demoing, when a song went in a different direction than its initial concept?

That is something that happens quite often. It’s kind of the process of how we write a lot of our songs. Going back and trying new things. Sometimes our best stuff is written in less than half an hour!

Are there any instruments, synths, pedals, plugins, mics, or pieces of outboard gear you are currently drawn to and how are you using them?

Some go-tos in no particular order are:

• Dave Smith/Oberheim: OB-6

• Moog: DFAM, Grandmother and

Matriarch, Minitaur

• Erica Synths: Perkons HD-01

• Chase Bliss Guitar Pedals: Thermae, Habit, Mood MKII, Genloss MKII

• Death By Audio Pedals: Reverbnation, Apocalypse

• Old Blood Noise: Procession, Reflector

• Korg: Kaoss Pad 3

• Turntable for sampling vinyl

• Mellotron

• Tascam 4 Track

• Teenage Engineering: OP-1

• UA: Apollo X8’s

• Roland: Juno 60, TR-8S

• Upon 251 Mic

• Tube Tech Compressor

• Baldwin Upright Piano

• Guitars: Ernie Ball Guitars, Fender Strat, Fender Jazz Master, Gibson Les Paul

• Soundtoys

• UA Plugins

• Native Instruments: Kontact, Maschine, Kontrol, Kontrol S88

Crosses’ Shaun Lopez

Shaun Lopez (SLOPEZ)—producer, engineer, songwriter, and founding member of the goth-wave electro-rock band ††† (Crosses) with Chino Moreno (Deftones)—gives insight into his Victor Frankenstein-esque exploratory approach to bringing undiscovered sonics to life in his synth-ensnared creative space (The Airport Studios).

When did you decide to have your own creative space, and how did you approach putting it together? Did you have ideas about elements that were “must-haves” for it?

It started when I was in Sacramento as the guitarist for Far, recording and experimenting with sounds. Around that time, I was approached by a local band to work with them on a few songs. I was relatively new to producing—at the time I was working on Cubase and a basic computer—but decided I would try. We tracked at a studio [Hanger Studios] owned by John Baccigaluppi, the co-founder of Tape-Op [with Larry Crane]. He helped me set up, gave me some tracking tips, and words of encouragement—“You know what you’re doing, you’ll figure it out.” Soon after that, I worked with producer Dave Sardy along with Far [at the Magic Shop in N.Y.C.]. I learned by watching and asking him many questions. The combination of those sessions sparked something in me, and about a year later when I moved to Los Angeles, I made it a priority to set up a creative space. It started with an Ikea desk, speakers, software, and no racks, but gradually grew to where it is now— multiple synths, racks, and a piano. As far as a must-have piece, I wanted an amazing tube mic. I have one now, a U 47, it’s one that June Carter and Johnny Cash sang through.

How would you describe the creative process you undertake while working?

I am fascinated by sounds and for me, the creative process begins by picking a sound I have in my head and trying to recreate it. It can start by playing around on a synth, but I might also grab a blip of a sound that I have recorded on my phone. I will pull it up and create samples, and loops, then tweak them until I like what I hear. I have an entire library of folders of these snippets, or what I call “starters.” When working with Chino [for Crosses], we will often go through a few starters until we find something we are both drawn to, where we both say “Woah, we have to work with this!” Also, I am a very visual person, and when making music I always have something on the screen behind the board. What I see in the background can sometimes seep into the overall vibe of the music. There are even times when I turn up the sound and if I like it, I will capture, sample, and transform it.

Are there any new recording techniques or ways of capturing sounds that you are developing?

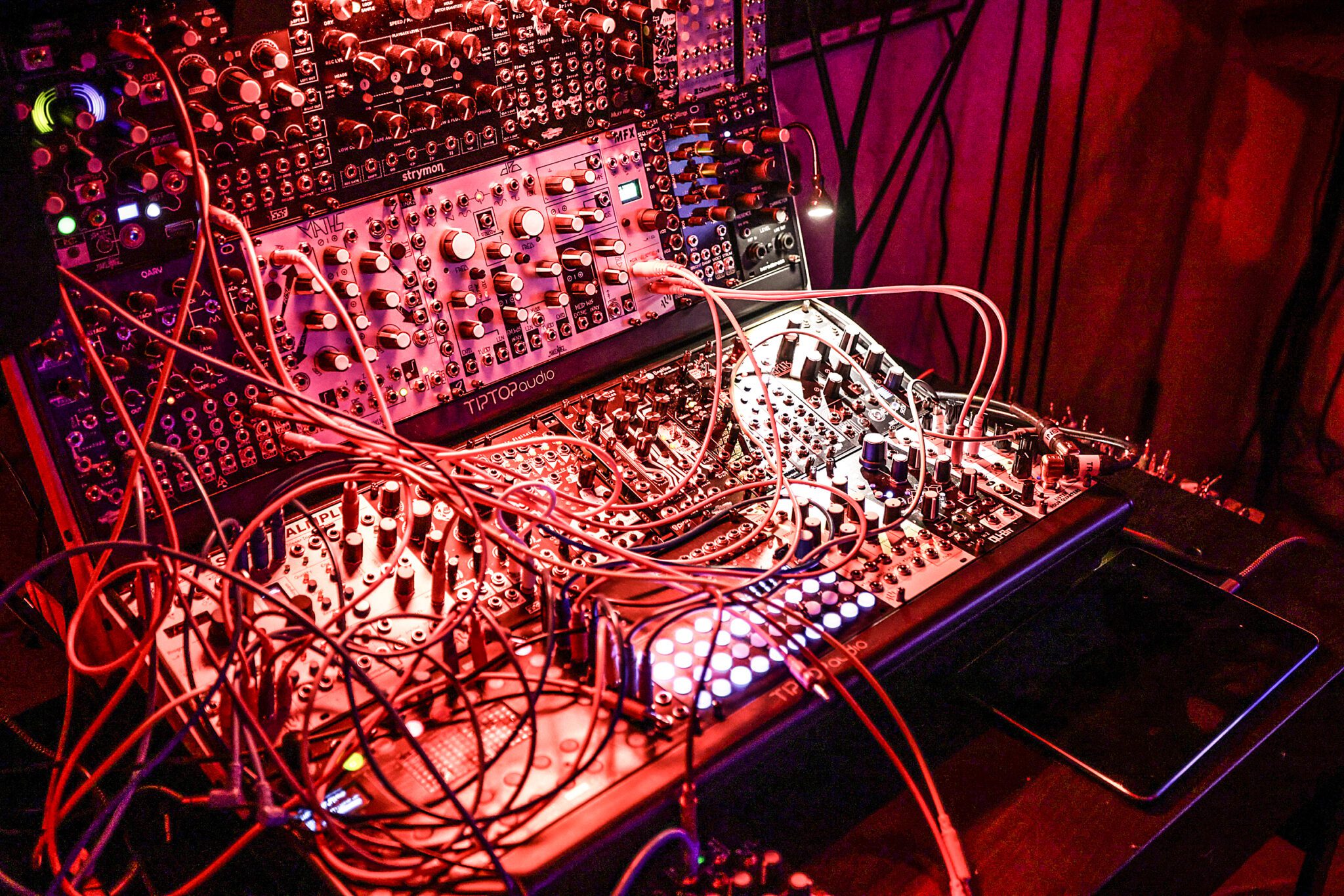

I love working with Eurorack. It is a modular synthesizer that can also be an effects unit, a sequencer, or a control processor—the possibilities are endless. I have a bunch of modules—envelope generators, oscillators, filters—which are developed by different companies, that I use to make all sorts of sounds. The hard part is knowing where to start and end. For example, if I want to create droney or ambient sounds I have to figure out what modules will work or if I will need to buy a new module to help me make the specific sound I have in mind. This ability to create a new synth every time I patch, creating a custom instrument, is what makes Eurorack so great.

Is there what you might consider a pivotal moment or a turning point in how you approach the songwriting and creative process?

I’d been playing guitar for a while and wanted to create different sounds from it. About ten years ago, just before we started Crosses, I decided I needed to learn piano. I taught myself by watching YouTube and trying to figure out why certain chords sound warm or dissonant. This led me into a bit of music theory, like suspended chords, or diminished fifths, and helped me grasp the importance that the piano has in writing certain styles of songs.

How to “hear” is also important in the creative process. I went into a mixing session with Ryan Williams while I was producing for Deftones’ Saturday Night Wrist. He was listening on a pair of NS-10s. I always liked listening to mixes through higher-end speakers, so I asked him why he was using NS-10s. He said, “They are honest, not super hi-fi, you hear the mistakes.” I realized that during the mixing process, it is best to hear what is bad, so you can make it good.

How do you go about creating the sonic atmospheres often found in your music? For example, how do you decide where to place the vocals in the mix?

With Chino and Crosses, his voice and atmosphere often go together. I will record Chino’s voice so that it’s subdued and softer in the mix. I will also put it through effects that help amplify the atmosphere in a song. There was one time when I was messing with the format and pitch on Chino’s vocals for “Vivien,” I moved the pitch down at the same time he sang “We drowned in silence, go down with you again…” When we listened to the playback, we heard a weird additional “possessed voice,” sounding as though it was going down, drowning. We love it when stuff like that happens.

Are there times you changed a song or sound while demoing, when a song went in a different direction than its initial concept?

There was a sound Chino and I created after hearing Peter Gabriel’s “In Your Eyes.” I think we started playing a triangle along with the rhythm of Peter’s song and sampled it. That became the kind of “bell-like” sound in “The Epilogue” that is carried throughout.

Are there any instruments, synths, pedals, plugins, mics, or pieces of outboard gear you are currently drawn to and how are you using them?

I have so many, but recently I’ve been drawn to the Morphagene module (a microsound tape and music synth module) that I use with Eurorack. I can create new or “unfound” sounds from ones that already exist and weird tape delays. I will often go into my YouTube playlist and pull up anything (as Shaun demonstrates with Harold Budd’s “Madrigals of the Rose Angel” in real-time) and tweak it to where it feels right. I can make the harp sound in the opening (of “Madrigals”) sound cinematic or take a splice of it and create something completely new. I could spend hours on one piece of a song and chop it up. That’s why I love working through it [Make Noise Morphagene].

Some of Shaun’s gear (besides his multitudes of guitars, synths, and mics)

• Ableton

• Roland Space Echo

• Roland TR -8S

• Roland System-8

• Steel Lap Guitar

• Fractal Axe-FX Processors

• Novation Peak

• Prophet 6 Synth

Eurorack: is a popular modular synth. The width and height of all Eurorack modules work within the same dimensions- height: 3U with U corresponding to standard 19” rack units of 1.75 inches and remains consistent. Eurorack widths vary depending on the function of the module. Width is measured in units known as horizontal pitch (HP). One HP is equal to 0.2” and corresponds with the hole spacing used for mounting modules. 84HP is the maximum usable space for modules that will fit within a 19” rack. Companies create various modules following the Eurorack specifications, making it easy to mix and match. The various modules from different companies communicate with one another using a Control Voltage format—an analog electrical signal from negative 10 volts to positive 10 volts over a 1/8 inch patch cable.

Modular Grid: (modulargrid.net) is a great resource when looking to create a modular, unfixed architecture synth. It helps musicians map out a virtual rack that is in line with their specific sound creation goals and provides suggestions for different modules. It will also break down what is needed in terms of power requirements and cost.

Learning Modular: (learningmodular.com) is a site that links to online courses and articles aimed at helping musicians wanting to understand and master modular synthesis.

Cases and power supply: Modules can technically operate on their own, but having a case with several modules and a power supply makes it easier to keep things contained and patch or link the modules together. ALM Busy Circuits is a case and power supply go-to. They have cases available in a range of sizes all including integrated powered bus boards. Cases are available in 3U 84HP / 6U 84HP / 9U 84HP / 3U 52HP / 6U 52HP sizes.

Modules: There are vast arrays of modules available to create sounds, a few to start:

Voltage Controller Oscillators (VCOs): Doepfer A-137-1 Voltage Controlled Wave Multiplier

Envelopes/LFOs: intellijel Quadrax four-channel function generator module

Filters: Angle Grinder is a quadrature sine wave oscillator or filter and distortion effect.

Voltage-controlled amplifiers (VCAs):

intellijel Quad Voltage Controlled Amp & Cascaded Mixer

Sequencers: TipTop Audio Circadian Rhythms gate sequencer

Reverb: Doepfer A-199 Spring Reverb

Delay: Qu-Bit Electronix Nautilus Sub-Nautical Complex Delay Network

Distort: Erica Synths Plasma Drive High-Voltage Distortion Unit Eurora

How to Mic an Upright Piano

Understanding the Upright Piano

Standard 88 key upright pianos generally have a frequency ranging from 27.5 HZ (the lowest note- A0) to 4186 Hz (the highest note- C8). The upright piano is categorized as a polyphonic, stringed instrument that creates complex melodies and harmonies. It can also be considered a percussion instrument due to the strings being struck by felted hammers and the ability of musicians to produce loud and soft rhythmic chords.

The build of an upright piano: Upright pianos can be straight-strung with the strings running parallel, vertically from the top toward the bottom of the piano, or “overstrung/cross-strung” where strings run in a diagonal “X” shape with the bass strings crossing over the tenor strings. It is more common for uprights to be overstrung as it can give the piano a more powerful, rich tone and provides additional tension. An “X” strung piano also allows for the treble and bass bridges in the piano to transmit the sounds between the strings and the soundboard more effectively. A straight-strung piano is often described as having an airier sound, while an overstrung piano has a full sound.

Upright Piano Placement

for Tracking

Upright pianos can be recorded against a wall, or if the studio space is large enough, at a slight angle in the middle of the room. If reflections are heard in either position, the sound can be dampened or deadened with heavy blankets placed on the floor, hung on the walls, or even over the back of the piano.

Microphone Basics

Microphones are transducers that change sound waves into electrical signals. Each mic has a unique sound quality and characteristics. The classification of a mic is based on how it converts acoustic energy into electrical voltages.

Dynamic microphones have membranes that move within a magnetic field. These membranes, or diaphragms, move slightly when sounds hit them, creating a small electric current. Dynamic microphones come in two varieties, moving coil and ribbon.

Moving Coil microphones use a magnet and a coil wrapped with wire. When the sound pressure hits the diaphragm, the coil moves across the magnetic field.

Ribbon mics use very thin strips of metal (sometimes gold) that also operate in a magnetic field. Ribbon mics are usually rectangle-shaped, have a very low output, and produce a softer, non-grating high-end.

Condenser microphones use thin metal diaphragms, flat and back-to-back with an electrical current running between them. When sound hits the metal, the current changes which is extrapolated as sound. Most condenser mics need 48 volts of phantom power to operate. Condensers usually sound bright and can track high-end frequencies more accurately than dynamic microphones. Tube mics are condenser mics that have tube power supplies and don’t need phantom power, as the sound is amplified through its tube circuit. This creates a warm sound. To help condenser mics handle higher sound pressure levels (SPLs,) the microphone will often have a pre-attenuation pad, which will lower the signal coming into the mic—usually anywhere between 6-24 dB, making it less likely for the sound coming in to distort. Many condenser mics will come with a -10dB pad. There are both small diaphragm and large diaphragm condenser mics—small diaphragm mics (1/2 inch or less diaphragm) are more accurate in reproducing the acoustic signals, whereas large diaphragm (normally greater than 1 inch) tend to be less accurate but produce warm and unique signals.

Microphone Patterns or Polar PatternS

A microphone’s pattern refers to its directional response and how it picks up sounds from different directions. Sound coming directly into the front of the mic is on-axis; all other directions are called off-axis.

Cardioid or unidirectional mics are most sensitive to sound coming from directly in front of the mic. Sounds coming from the rear and side are lower in volume than on-axis sounds. Cardioids essentially pick up sounds directly in the front of the mic., so if plotted on a 360-degree graph will look like a heart “cardio” shaped pattern.

Super-cardioid microphones are similar to cardioids in that they are unidirectional but are more sensitive to the sounds emanating from the front of the mic.

Hyper-cardioid microphones are also similar in pattern to a cardioid and super-cardioid but with an even narrower directional range.

Omnidirectional microphones pick up sound uniformly, with an even frequency response from all directions around the microphone in a full 360-degree sphere.

Bidirectional or Figure-8 microphones pick up sounds equally from the front and back of the microphone on either side, but are least sensitive to sounds that are 90 degrees off-axis. They create a figure 8 when plotted.

Mic Preamps or Mic Preamplifiers

Mic signals are weak, so it’s necessary to boost the signal to line level to be used, read, or processed by other equipment—computers, outboard gear, consoles, etc. A mic preamp will at times come with a pad that cuts the level going into the mic pre. If the pad button is punched it reduces the volume which can reduce circuit distortion (if desired).

Upright Piano Miking Techniques

1. Behind the pianist. The piano lid could be opened or left closed, depending on the desired sound. Remove the upper panel revealing the strings. Position two stereo microphones just above and along each side of the pianist approximately 30 inches apart. One mic pointing toward the high end with the other pointing toward the low-end of the keys/strings.

2. Near the soundboard. The soundboard is a wooden panel on the back of the upright. Place two microphones spaced approximately 6 inches to 20 inches away from it (depending on the mic and the desired sound) and a few feet apart, so one mic is picking up sounds from the high strings, while the other is picking up the lows.

3. Underneath the piano. This amplifies sounds! Remove or open the panel beneath the keys which will expose the “harp” of the piano. Aim two microphones, one on the bass and the other on the treble sides underneath the keyboard, angled slightly towards the strings.

4. Above the piano. Take the lid off and position two microphones (one on the bass side and the other near the treble side) from above toward the hammers and strings approximately 6 inches away. This distance is a good starting point, but moving the mics further away can produce unique sounds as well.

5. Open Room. Find the live room’s sweet spot. Experiment with different microphones, positioning them closer to the piano, further away, above, or below. One mic, two, three—the possibilities are endless.