During January-May 2022, Micky Dolenz the Voice of the Monkees and Felix Cavaliere’s Rascals are teaming for live dates in 2022. Felix has a new album due soon and an autobiography coming in March.

Micky and Felix's trek kicks off January 22nd at The Palladium in New York City and includes dates April 23rd in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Red Bank, New Jersey on May 12th and a May 14th appearance at the Patchogue Theater, Patchogue, New York.

A few years ago I saw the duo perform a stellar show in Los Angeles and I’m excited they will hit the road together again.

I have my own bio-regional relationship with Dolenz and The Monkees that began in Hollywood during late 1965.

My mother Hilda was employed at Columbia Pictures on Sunset Blvd. from 1962-1972, and primarily during 1965-1968 for Raybert Productions, helmed by producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider, overseeing The Monkees at the studio in Gower Gulch. Paul Mazursky and Larry Tucker had developed it for TV adaptation.

Hilda helped type the television scripts for The Monkees, was in the stenography pool on the lot and did dictation for author and screenwriter Lillian Hellman. She worked for Marty Erlichman who managed Barbra Streisand and Peter Guber in his first job in 1968 at Columbia as a management trainee.

I first encountered the four members of The Monkees when they held their first press conference in 1966 before the series was broadcast. I remember two events introducing the Monkees, one in Hollywood at the Columbia Pictures studio and in Burbank at the Columbia Pictures ranch.

During 1966 my brother Kenny and I along with our mom assembled the first-ever yellow colored press kits introducing The Monkees on our 5th Street kitchen table that unit publicist Howard Brandy created. Howard had worked on the Beatles’ movies Hard Day’s Night and Help! Nick LoBianco designed the Monkees’ guitar logo.

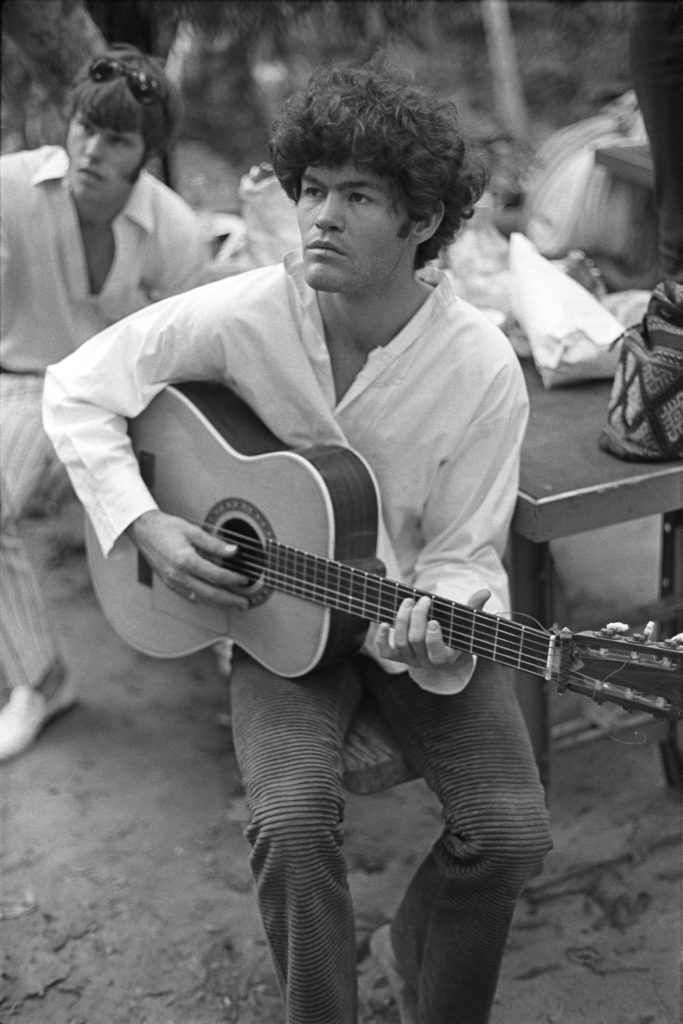

Micky Dolenz in 1965 was a former child actor knocking around Hollywood, looking for his next gig. Peter Tork was a folkie from Greenwich Village. Michael Nesmith possessed real chops-a guitarist and songwriter bursting with ambition. And Davy Jones was an English lad with a Cockney charm and stage training.

Producer Bob Rafelson had been a story editor on the TV series Play of the Week and later worked as an associate producer for Desilu Studios and Screen Gems. Bert Schneider’s father Abraham Schneider was President of Columbia Pictures. Schneider’s career began at the Screen Gems television division where he met Rafelson and formed Raybert Productions, the future home of The Monkees.

Davy Jones at the time was a contract player with Screen Gems/Columbia, and had appeared onstage at the Music Center in Los Angeles when writers Paul Mazursky and Larry Tucker said, “We’re going to write a show for you.”

Davy was already in The Monkees before Rafelson and Schneider held auditions in Hollywood for their TV endeavor about a rock group. Micky Dolenz, Peter Tork, and Michael Nesmith were cast in The Monkees NBC television series which debuted on September 12, 1966.

I was around the Raybert offices monthly and on the set of The Monkees a handful of times watching segments of episodes being taped.

I encountered Stan Freberg, Godfrey Cambridge, Dick Kiel, Paul Mazursky, and Rupert Cross on The Monkees’ production and met Frank Zappa, booked as a guest along with Tim Buckley and Charlie Smalls.

The Columbia studio had a massive wardrobe department, assorted props and costumes previously used for The Three Stooges shorts in the 1930s and ‘40s.

Jack Nicholson and Dennis Hopper occasionally were in the studio’s coffee shop. Jack co-wrote HEAD, the Monkees’ feature-length film. He was into Bob Dylan and caught his 1963 and 1965 Hollywood Bowl concerts. I spoke with Larry “The Mole” Taylor the bass player in of Canned Heat and guitarist Gerry McGee who both played on The Monkees’ albums. Composer and conductor Stu Phillips provided the background music for the 1966-1968 programs.

The Monkees shooting schedule was high energy. We were politely instructed not to speak with the directors toiling on the clock. James Frawley did half of them. One frame-changing aspect of The Monkees’ ongoing telegenic success was employing many first-time directors and the implementation of quirky interstitial editing techniques that drove the visual momentum.

In 1967, The Monkees won two Emmy awards for Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Comedy.

The Monkees recorded for Colgems, distributed via RCA Victor. It was a joint 1966-1971 venture between Screen Gems, the television division of Columbia Pictures, and RCA Victor.

At Raybert 1966-1968 there were no entourages in this coveted Hollywood war zone. It was an environment where the seeds in the top soil of BBS Films were planted. Bert Schneider told me the success of The Monkees made the 1969 BBS movie Easy Rider possible.

During 2014, Micky Dolenz invited Gary Strobl, the ultimate Monkees scholar, documentarian and Diltz’s librarian/archivist and I to his home in Southern California to conduct an interview.

It’s an unpublished dialogue, utilized as research for a coffee table book manuscript about The Monkees which Gary, Henry, my brother Kenneth and I have collaborated on this past decade.

Micky Dolenz and Harvey Kubernik 2014 Interview

Q: You were in show business before The Monkees and done promotions.

A: For me, and I’m not speaking for anybody else. I had already done all of this stuff. I had already been on a big promotional event. I rode my elephant down Fifth Avenue in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade and on stage with the Rockettes. On trains going across country doing whistle stop promotions for Circus Boy. So it was like I’ve done this. I had been through the process. Press things. Been there and done that.

Q: You played guitar on the Circus Boy press tour.

A: I did “Purple People Eater” by Sheb Wooley. I did Billy Williams’ “Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter” [a Fats Waller tune] and David Seville’s “The Witch Doctor.” Songs I was hearing on radio stations in Los Angeles and learning on my guitar. I must have started guitar when I was eight or nine. Classical guitar and then folk music. I would play when kids came over for a party. Or I would go to a party. I wasn’t Segovia but I could do ‘Tom Dooley.’

“My first public appearance was in 1957 opening for Bimbo the elephant at Kennywood Park in Pittsburgh. I opened for the elephant. Two songs with a local bandstand band. They had fair outfits on and backed me on “Witch Doctor” and “Purple People Eater.” And then the elephant came on. We went to places like Pittsburgh and Chicago. A big press event without the elephant. Then New York and Grand Central Station. I was introduced in the middle of a Radio City Music Hall thing.

Q: Before The Monkees television series you auditioned for three TV pilots.

A: I don’t remember anything about them except the one that became The Happenings. I don’t know why. Maybe because it did go to pilot. I remember my audition for The Monkees very well. I had an agent Ted Wilk who said, “You have an audition.” I went down. I think the reason I remember it well because it was in the same building and possibly the same office that I auditioned for in the fifties for Circus Boy. Columbia Pictures and the executive offices were all in a building on Gower. It was one of the ugliest offices. (laughs). It looked like a brick wall. Paramount had the gate, and Universal had the entrance, and this was a door. Anyway, I went to the audition.

“You’ve heard the story a million times. Obviously I got a call back. The next one was probably the interview. Asking questions and I think it was on the set of The Farmer’s Daughter. The next one I’m pretty sure was the musical one. They had a back lot with guitars and drums, keyboards. It was kind of like a jam, an open mike. That’s where I played “Johnny B. Goode” on the guitar. And the last one that I remember was the screen test with scripts and scenes. I think by then there might have been eight candidates left.

“The only one I remember was Davy. I don’t remember Mike, That’s because Davy and I just had a lot in common. We had both been in television, and he had been on stage. I had been a child on stage. Maybe they paired us up. I do remember one of the major scenes I did with Davy, a twosome. We then came up with a bit of shtick where he and I were wearing hats. Bill Chadwick, Michael and Peter were there. Bill later worked with us as a songwriter and on the series. I recall Davy and I had a lot to talk about concerning TV, film, and stage. And that was it. We had a jam.

“I went back to school at Los Angeles Trade-Technical College in downtown L.A. to study architecture. I never was formally trained in acting. I had guitar lessons. But never singing or acting except acting through my mother and father. I was doing day jobs on TV shows. I was going to school. I wanted to be an architect. I went to Valley Junior College. If the architect thing didn’t work out I was gonna fall back on show business. That was my mantra.

Q: Were you drafted or received a notice of induction to take a physical.

A: I did get a draft notice, a draft card. Between my bad leg [owing to Perthes disease] and that I was too skinny. 119 pounds and living in an apartment. And I couldn’t see. I was near-sighted. I got 4F status.

Q: I know you graduated from Ulysses S. Grant High School in Van Nuys, located the San Fernando Valley. Where were you living at the time of The Monkees audition?

A: In Reseda somewhere on Sherman Way, an apartment building with Tiki and palm trees. That was where I moved when my parents moved up north. My mom remarried and moved to San Jose. I was going to school and stayed for that semester. My first kind of proper girlfriend lived in Nevada and we had a very serious relationship. I was going back and forth to San Jose. I had stayed in my grandmother’s house.

“It’s August 1965, I’m going to school and watching the L.A. Watts riots, back and forth to San Jose and driving up and down the 5 freeway back and forth trying to go see this girl.

“But I said to my mom I wanted to stay in L.A. That is where my friends are and I’m going to school. And she organized it and I got little single one room apartment. On Reseda Blvd right by Sherman Way, right across the street from this girl. And I would walk out and stare at her window and drive away.

“I think my car was a 1962 black Grand Prix 4 speed. Incredible car. And that’s where I was living when my agent called for The Monkees audition. Sitting in that apartment. I was drumming with the Missing Links. I stayed in touch with Mike Swain of the band after they fired me. And then at some point my agent Ted Wilk called me and said ‘you got it. You are one of The Monkees. You got the pilot.’ I then traded my car in for a Volkswagen Beetle.

“I remember being excited but not when I got Circus Boy. I really remember that. I was ten years old. I was Mickey Braddock then. I remember walking out in the parking lot of my dad’s restaurant looking up at the stars ‘this is really important.’ Even at age ten.

“I knew The Monkees was going to be a pilot. And I knew that pilots mostly do not get sold. I saw the ad in Variety. It wasn’t in the music papers. Casting director Eddie Foy III said something about music because it was about a band. So I suspect everyone they saw, some who I know, like Paul Peterson. I bumped into him in the hallway and Paul Williams, and a friend who I sang with in a folk kind of thing and he called me and said “tell them we worked together.” When the casting director came up to my name, ‘what has he done? Circus Boy. And he is in a band, plays bowling alleys. Does open mike nights.’

“Mickey Braddock was my stage name. It wasn’t like I was coming off another TV show. They were going for four kids who just jumped off the screen. If I was producing that is what I would have done. Not “I gotta have a keyboard player…”

“They were casing for four characters that were charismatic and different. And that was an important element. They were doing an ensemble show. And I think the music aspect was something they would worry about down the line. Let’s cast the show. And they were going to put us into rehearsals for a year. ‘Cause it was a TV show, as I have often said, about a band. It wasn’t a band. And the producers knew that. They had great visions of what it could be.

“As you see on the screen test it was comedy and acting. We did one little jam. I suspect but don’t know the music was not at the top of the list of their priorities. It had to be there. And we had to be comfortable around music. But it was heavily weighted toward the improvisation. The fact that I had the musical background they saw me.

“The first time I remember when the four of us together as The Monkees was at the wardrobe fitting. And I remember when I would drive on to the lot past the guard gate, the same guard was the one I knew from Circus Boy. I had an on set tutor and I remembered the teacher, Lillian Barkley, and she was still at Screen Gems when I went there for The Monkees audition. As I said before, before I got the part,

“I remember walking around. I would be there for other things, saying hi to Lillian, “Boy, I really want to get this one.” I wasn’t thinking about the money. I’d like to get the job and a check,’ I told her ‘put in a good word for me.’ I knew The Monkees were going to be different. I was coming from a show biz family, and so much was second nature by then. And I had already done a series. I recall at the middle of the lot. “Oh hi. This is Mike.’ ‘I’m Micky. Peter, Davy. Nice to meet you. Great. Congratulations. You guys are The Monkees.”

“I’d been through the process. But I didn’t get enormously invested in the whole thing. I knew it was a pilot. Late November 1965 I was still going to school and would have taken the week off. I went down to Hotel Del Coronado and went back to school at Trade Tech. At the time I was never that comfortable at improv when we did the pilot. We’d only just met each other. Around the pilot there was a buzz about it. And I was kind of encouraged to be kind of goofy and improvise and be unusual. My mother said to me after the pilot.

Q: You had various day and night jobs around Hollywood. And you were embedded in rock ‘n’ roll. You parked cars at the Red Velvet nightclub on Sunset Blvd. and played amateur nights clad in a shiny sharkskin suit.

A: I had worked at Wallichs Music City. Hollywood and Vine. Bobby Darin came in one day. I had already recorded my first single. “Don’t Do It” before The Monkees, with members of the soon to be known Wrecking Crew. Glen Campbell, Earl Palmer, Joe Osborn and a keyboard player. I didn’t know who they were. I became friends with Glen Campbell during The Monkees. At one point, Glen said to me “I don’t know if you remember but I was on your first session.” “What!”

“I also used to frequent a place called the Omnibus, a coffee house. It was in the early sixties. This was probably the closest thing to a cusp between the beatniks and the hippie area. It was on Cahuenga or Las Palmas. I remember clearly it was my first foray into post teenage life and the adult world. I’m going to Valley Junior College, age 18 or 19, well after Circus Boy, no drinking, and only coffee. This was bikers, and beatniks. No paisley, no bell bottoms, people in black. And still snapping their fingers and reading poetry.

Q: History has shown us the group had chemistry and was a magical outfit.

A: It obviously clicked and it had chemistry. It’s almost the absence of any conflict that probably was, you know, more to the point. Even in the pilot and early episodes it was very clear to us that we immediately when we got a script with scenes who was the right person to say that line. And we would often say, ‘that is a line for Peter, not Davy.’ On some re-writes we would just swap lines.

“The characterizations were like The Marx Brothers. And going back to the audition process, I heard they had gone to the Lovin’ Spoonful. Similar in many ways in terms of personalities as the Beatles even. Things that happen in a group who are like-minded and have the same taste in music. And they have the same dynamic which is wonderful for music for recording.

“The singularity of musical vision would never work on television in terms of comedy and the drama like the Marx Brothers if all of them were like Groucho and all of them were doing Groucho. Like with Friends, if all the girls were Lisa Kudrow. It doesn’t work. You have to have the distinction. I did the pilot and went home.

“I remember hanging out at Mike’s place. He had an apartment. I remember hanging out with Peter waiting to hear from my agent. Mike had a drum kit in his apartment. He gave me a drum lesson before the series started. Shot in November 1965 and we were getting ready for the TV up fronts in New York. January 1966. It moved fast. But for the two months we were hanging out. I was going to school. And the series got picked up. That is when I quit school.

Q: There were people considered and given drum kits like Rick Steininger, a roommate of Denny Doherty.

A: Partially because there were some lingering concerns about me being drafted. I remember them asking my agent about the draft, who knows if that was an issue or not. It could have easily been.

Q: Your distinct drum style. Your drum kit set up was different. You had an innate sense of rhythm.

A: In the pilot I didn’t know I was going to be the drummer. I remember being told by Bob or Bert or both, you are the drummer. (laughs). They had a lot of guitar players. Looking back of course, the idea was to have Davy to be the front man, Mike on guitar. “OK. When do I start?” I remember immediately starting drum lessons. Later on I watched Earl Palmer and picking up tips from him. But the first teacher I had was right down off of Gower at his studio or maybe on the lot. I sat down at the traps. The kit was set up in a traditional way.

Q: You had Perthes disease which affected your hip joint and right leg, which was weaker, and played a part in you adapting an unorthodox drum set up which mixed equipment as right-handed and left-footed.

A: I started playing and because of my right leg which still gives me trouble to this day, it got very sore, and arthritis kind of thing very quickly. I got sore as a kid and teenager playing sports. And I started playing and he said switch it around and play from scratch. “Your left leg is the strongest one.” “I’m right handed.” “Turn the bass drum over there, snare here.” And because of that switch using my left foot, right foot would have been awkward, but now your right leg has to play behind. That was interesting. He switched the hi-hat and the bass. The hit-hat was on my right leg which doesn’t do as nearly as much.

“That meant that now I’m playing open. I got a drum pad, a practice pad at home and worked my ass off. I drove up to San Jose and sat there in the passenger’s seat playing the drum pad. I wanted to look good and play good. Preparation. In the beginning there was no thought of recording. That was way down the road. This was all about getting ready for the show and the series.

“Early on when they pulled the trigger on the series, there are very early press releases and photos where I am Mickey Braddock on them. Right at the last moment it might have been one of those situations where I had to make up my mind on the last name. I don’t remember why. Maybe my mom said something. Because it was confusing as well as driver’s license and ID’s and stuff. At some point I said “Micky Dolenz.”

Q You used your own name in the series.

A: That must have been Bob and Bert. I often wonder what would habve happened to us in many ways and what would have happened to the whole brand and the marketing, plus us as individuals if we would have had character names. That is probably the biggest unknown question about The Monkees. Would it would have been as successful? More successful? Less successful? If after The Monkees would we have been able to move on and do other things as actors and entertainers having played the part.

“I have the pilot script where we have names like Biff, Rick, Wendell. Davy is the only one. And the whole thing initially about not playing the instruments been as big a deal with the fans or we not playing as deeply and as passionately as them? We will never know…

“Look at Friends. The fans are very passionate and the show was very successful and the actors were able to move on. But then you look at someone like Leonard Nimoy and it wouldn’t have mattered. He’s still Mr. Spock. Fine actor.

“I don’t know who made the decision about names, corporate or Bob or Bert. I do know the pilot almost didn’t sell. I heard after the fact. All I know and what I’ve heard was that the pilot did not do well. And the feedback was it wasn’t gonna work. That’s when they went back in took out the manager of the record shop and added our screen tests. Those are the two main things.

“I always felt NBC was scared of it from the very beginning. I’m sure they were after the pilot got picked up. And then things like the Monkeemobile and the musical equipment started happening in January 1966. That’s when the wheels really started turning. The endorsements. Cars, Pontiacs.

Q: I seem to remember there was a moment when you really knew The Monkees had made a big impression on the public. You were at the newly opened Fashion Square in Sherman Oaks, California in the mall and recognized.

A: That was Christmas of 1966. Two months after the show was on the air. That was the first time I noticed and realized ‘Holy shit! Something is going on here.’ I was only at the studio and at home. The show was just on the air. I had no idea what was happening. There was a big “Last Train to Clarksville” promotion done in conjunction with local radio station KHJ. I remember the train. We were flown in by helicopters. Landed on the beach. All these plants. 50 girls who were hired that were contest winners and on the train.

“Some idiot (laughs) said “you guys are gonna have to play on the way back.” Because we had been practicing. But of course how do you set up a band in a train. When the train starts and the cymbals are flying all over the place and crazy amps. It must have been God awful. We played “Clarksville” and two other songs. Maybe a couple of Mike’s tunes.

Q: Your group’s first public appearance.

A: I guess so. No one figured out that the train rocked back and forth. How would they have even gotten power to the amps?

Q: They were showing one of the pilot episodes in a box car. When was the first time you heard the group on the radio?

A: That I do remember, because I had never heard myself on the radio. I was living on with Davy on Easton off of Benedict Canyon and he and I and John London rented a house after I moved out from an apartment in the San Fernando Valley. I had another apartment an upgrade from the one before I got the show. Coldwater and Riverside. That is where I was when I even got the pilot. I moved to this house with Davy when the series went and John London who was Mike’s stand-in and friend. Davy and I were coming back from the set and it had been announced on KHJ that it would be Monkees Day or something like that. So we were listening. And it started playing as we pulled up to the house. We looked at each other “Wow!”

“We were at Bert Schneider’s house when we saw the actual series debut. And I believe Natalie Wood was there. I think he was dating her at the time if I’m not mistaken. I remember Natalie Wood because she was hot and I always remember liking her and when I walked in and there was Natalie Wood. Bob Rafelson and his wife Toby were there. I don’t think I brought anybody. Every few weeks I would watch an episode.

Q: I always dug that The Monkees gave guest spots to comedians and actors who were stars of the forties and fifties.

A: I remember Jerry Colonna, Stan Freberg, Hans Conried and Lon Chaney Jr. I remember Jerry Lewis coming down on the set as a director. I was a huge Jerry Lewis fan. The episodes were shot back to back. And so it was a continuous episode from my point of view. We would typically start on a Monday and finish on a Wednesday. Start on a Thursday and finish on a Monday. Start on a Tuesday and finish on a Friday. It was one episode…

Q: The enduring and endearing influence and impact of the Monkees. Rick Rubin and Steven Van Zandt have touted your group to me during interviews.

A: I’ve often thought the Monkees often hit pop music. Dr. Timothy Leary said in that book, Politics of Ecstasy, “The Monkees brought long hair into the living room.” And I think that may be the legacy. It made it OK to be a hippie, have long hair, and wear bell bottoms. It did not mean you were a criminal, a dope smoking fiend commie pervert. That’s what happened. A kid says, “Hey mom, the Monkees have long hair and wear paisley bell bottoms.”

“You know, let’s not forget that The Monkees were a TV show about a band. An imaginary band that lived in this beach house and had these imaginary adventures. It was theater. It was probably the closest thing to musical theater in television. It was about this band that wanted to be famous, wanted to be the Beatles, and it represented in that sense all those garage bands around the country and the world.

“On The Monkees show, the Monkees were never famous, it was all about the struggle for success that made it so endearing I think to the public, anyway.

“In fact, one of the most important things, I think The Monkees’ show contributed to the culture was the idea that you could have longhair and wear bell bottoms and you weren’t committing crimes against nature. At the time the only time you saw people with longhair on television they were being arrested or treated as second class citizens.

“I remember Ringo once, years later, telling me how the music business has changed so much. ‘You know, all you had to do in the old days was show up with your drums and you were in the band.’ (laughs). And, that’s true.”

Photos by Henry Diltz

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, Neil Young Heart of Gold, Canyon Of Dreams, The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For November 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child published by Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, most notably, The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

This century Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century.

During 2020 Harvey Kubernik served as a Consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood which debuted on EPIX television. In 2022 Kubernik is involved in music documentaries and for the last decade is Editor-In-Chief of Record Collector News magazine.