George Harrison’s debut solo album All Things Must Pass was recorded May-October 1970 in London at the Abbey Road, Trident and Apple studios. It was co-produced by Harrison and Phil Spector, with assistance from engineers Ken Scott and Phil McDonald.

Contributing to the sessions were musicians Eric Clapton, Klaus Voorman, Gary Wright, Ringo Starr, Billy Preston, Pete Drake, Dave Mason, Gary Brooker, Jim Price, Bobby Whitlock, Carl Radle, Bobby Keys, Ginger Baker, Peter Frampton, Tony Ashton, Jim Gordon, Alan White, members of Badfinger, and John Barham, who provided the orchestral arrangements.

Upon initial release on November 27, 1970, the triple-LP topped the sales charts around the world and George became the first Beatle to have a solo number one single in both UK and America with the album’s initial single, “My Sweet Lord.” Harrison penned the album’s opening track, “I’d Have You Anytime” with Bob Dylan, who also wrote another song on the album, “If Not For You.”

Upon initial release on November 27, 1970, the triple-LP topped the sales charts around the world and George became the first Beatle to have a solo number one single in both UK and America with the album’s initial single, “My Sweet Lord.” Harrison penned the album’s opening track, “I’d Have You Anytime” with Bob Dylan, who also wrote another song on the album, “If Not For You.”

There are recurrent and still relevant lyrical themes on All Things Must Pass reflecting Harrison’s spiritual quest: “Isn’t It a Pity, “My Sweet Lord,” “What is Life,” “Hear Me Lord,” ‘Wah-Wah’ and “Beware of Darkness,” his ongoing devotion in Hindu religious mythology, the Hare Krishna movement, Indian classical music, and southern gospel, gleaned from George’s relationship with members of Delaney & Bonnie and Friends.

In Dream Weaver: Music, Meditation, and My Friendship with George Harrison by Gary Wright (Tarcher/Penguin Random House), Wright acknowledged All Things Must Pass.

“When he first played ‘Isn’t It a Pity’ for me, the song we would be working on that day, I silently marveled how beautiful his writing was, both melodically and lyrically: I wound up playing keyboards on the entire album, aptly named All Things Must Pass, As time went on, the sessions became smaller and more intimate, moving away from the large production concept Phil had created for some of the earlier tracks we had recorded.

“The rhythm section shrank down to George, Klaus Voorman or Carl Radle on bass, Ringo or Jim Gordon on drums, Eric Clapton, and me on piano, organ, Wurlitzer piano, or harmonium. To me, the quality of songs on All Things Must Pass was nothing short of amazing.

“Many were true masterpieces, but what really took me back were his unusual lyrics. Songs like ‘My Sweet Lord,’ ‘Beware of Darkness,’ ‘Art of Dying,’ and ‘Hear Me Lord’ had spiritual messages, something I had not heard before in pop music—especially to the degree that he used them. He was breaking new ground as an artist to an even greater degree than he had done in the past, and his slide guitar playing throughout the album set a new trend among guitarists throughout the world. The control room at Abbey Road became transformed into George’s sanctuary, with incense burning alongside the photos of Indian saints that he placed on the mixing console.”

It was in January 1970 when Harrison extended an invitation to record producer/songwriter Phil Spector to participate in the recording of John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band single “Instant Karma!”

This association subsequently led to Spector being asked to salvage the Beatles’ Get Back rehearsal tapings, eventually issued in 1970 as the Let It Be album, and then co-producing All Things Must Pass, after Phil heard Harrison’s demos at George’s Friar Park home.

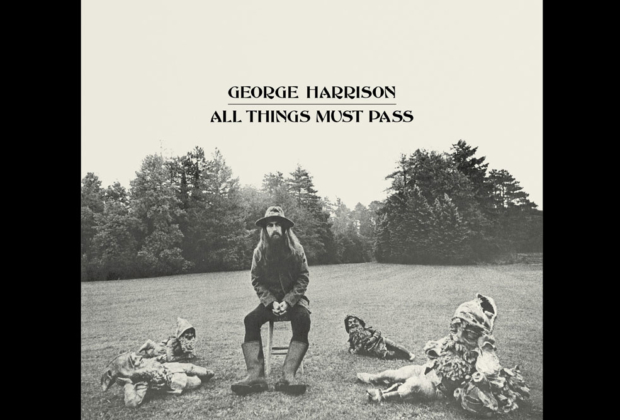

The black and white album cover photograph was snapped on a lawn at Friar Park by Barry Feinstein.

All Things Must Pass was shipped to retail outlets the last week of November 1970.

Reviewer Richard Williams in Melody Maker enthusiastically touted the endeavor as “the rock equivalent of the shock felt by pre-war moviegoers when Garbo first opened her mouth in a talkie: Garbo talks!-Harrison is free.”

In addition, Williams wrote another review for The Times, suggesting that of all the Beatles’ solo releases available, Harrison’s album “makes far and away the best listening, perhaps because it is the one which most nearly continues the tradition they began eight years earlier.”

“When All Things Must Pass came out I sat down and listened to it for 3 days,” record producer/author/and deejay Andrew Loog Oldham told me in a November 2020 telephone call. “It was the first album that sounded like one single.”

The collection of Harrison compositions spawned the hit singles “My Sweet Lord” and “What Is Life.”

I was given a limited edition copy of the promotional album A Conversation With George Harrison February 15, 2001 where Harrison cited Spector’s work with the Beatles and how he came to be the producer of both Lennon and his first "proper" solo albums.

"Well, we knew him a little bit. He needed a job (laughs). And Phil was around, if you remember he was brought into London by Allen Klein when we had done the record Get Back or Let It Be, it became the Let It Be record.

“Let It Be was supposed to be just a live recording and we ended up doing it in the studio and nobody was happy with it. But, it was troubled times. Everybody listened to it back and didn't really like it and we really didn't want to put it out.

“So, later down the line Klein, this guy Allen Klein brought in Phil Spector and said, 'Well, what do you think about Phil Spector looking at the record?' So, at least John and I said, 'Yeah, let's see.' We liked Phil Spector; we loved his records. So, let him do it and he did what he did and then you know everybody knows the rest. And so he was around and one day I was with Phil and I was on my way to Abbey Road to do 'Instant Karma.' And so I made Phil go with me and that's how he got to do that record as well. This is how we first started working with him."

The roots of All Things Must Pass stem from the Spector sonic tree and the implementation of his groundbreaking Wall of Sound production techniques.

Spector’s hit tune “To Know Him is To Love Him” was covered by the Beatles on their Decca Records audition recording session on January 1, 1962 and performed when the band were booked at the Cavern in Liverpool, and later recorded at their BBC Radio broadcasts.

Spector, as a session guitarist for the Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller songwriting and production team, worked with Lavern Baker and the Drifters at Atlantic Studios. He later co-produced with Jerry Wexler the original studio version of the Bert Berns and Phil Medley-penned “Twist and Shout,” by the Top notes, subsequently re-worked by Berns, which became a hit record for the Isley Brothers, then landing in the Beatles’ stage and recording repertoire.

On January 28, 1964, the Beatles encountered Spector and the Ronettes at a party at the Green Street home of deejay and Decca Records promoter, Tony Hall. By next month Phil was a passenger on the airplane with the Beatles when they landed in New York on February 7, 1964.

“We met a few people through Phil Spector,” remembered Paul McCartney in the Beatles’ Anthology. “We met the Ronettes, which was very exciting, and various others, such as Jackie DeShannon, a great songwriter, and Diana Ross and the rest of the Supremes. They were people we admired and as we went on we met them all-all the people who were coming up as we were coming up. It was a matey sort of thing.”

George Harrison in March 1966 provided a sleeve endorsement for the Spector-produced Ike & Tina Turner River Deep, Mountain High popular 45RPM in the UK when it first charted.

"It is a perfect record from start to finish. You couldn't improve on it." John Lennon called it a “masterpiece.”

“Phil Spector was born on Christmas Day in 1940,” poses writer and author Daniel Weizmann. “But I see him as the first truly post-Holocaust American Jew. He refused to grovel and play the Borscht Belt guy, the entertainment guy. And yet he had one foot in that old world grandiosity. His music was for the new utopian free-spirited teenagers, but it also contained the secret mania of having grown up with the shadow of genocide and the bomb. He meant business.

“In a way, he is the link between Lenny Bruce and Bob Dylan. Once Phil planted the seed, the sixties just had to happen.”

“Spector’s Wall of Sound has always sounded to me like a gesture of optimism fitted to an optimistic time,” indicates poet/writer and deejay Dr. James Cushing.

“Spector's early hit records --Crystals, Ronettes, Darlene Love, the Xmas album -- all seem to want to evoke a response like this from the listener: Here we are, just kids living in a world made by and for adults, and to the adult world, our romantic feelings for each other are trivial, private, childish moods we'll outgrow. However, to us, these feelings are massive, mythic, life-sustaining moments of energy and grace, and Spector's 3-minute teen operas capture and magnify those moments in the public arena. ‘Da Doo Ron Ron’ confirms our emotional existence in an adult world that denies it.

“The public instantiation of private feeling. Hence the undercurrent of triumph in the songs, even ‘You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling’ by the Righteous Brothers (my personal all-time favorite Philles records thing). A private plea, a ‘moment of poignant longing,’ yes -- but made to sound as massive & monumental as it feels... and we get to join in the singing.”

In a 1988 interview for Goldmine magazine, I asked arranger/producer/songwriter Jack Nitzsche at the Musso & Frank Grill in Hollywood about helping build Spector’s Wall of Sound.

“It happened over a period of time. I don’t know who coined the term. The sound just got bigger and bigger. One time at Gold Star Recording Studio we cut the Crystals’ ‘Little Girl.’ Sonny Bono was the percussionist on the date. He came into the booth, and said it had more echo than usual, and it wouldn’t get played on the radio. The echo was turned way up high. Phil said, ‘What’s too much echo? What does that mean?’

“Phil was smart enough to say, ‘Wait a minute listen to this.’ If you notice, there’s more echo on each song we cut. It hadn’t been done like this before. People on the business side, the promotional side of the record industry, felt it was different. He didn’t listen to them.

“I remember engineer Stan Ross, who was co-owner with Dave Gold of Gold Star, telling us many times that the echo chambers were acoustically and geometrically designed to get the right amount of balance and reverb. That added to the impact of Phil's recordings. I loved the echo. It's like garlic. You can't get too much.”

“I used to have a theory,” Gold Star engineer Larry Levine confided to me in 2002, “and I don’t know if it’s right or wrong, but part of the reason we took so long in actually recording the songs was that Phil needed to tire out the musicians, or they got to the point where they were tired enough so they weren’t playing as individuals. But they would meld into the sound more that Phil had in his head. Good musicians start out and play as individuals and strive to play what Phil wants.

“As a matter of fact, Phil once said to me the bane of his recording existence was the drum sound. A lot of people attribute to echo to what Phil was doing. The echo enhanced the melding of the Wall of Sound, but it didn’t create it. All of this was happening and the echo was the glue that kept it together.”

In the May 31, 1975 issue of Melody Maker I published an interview with Phil Spector, culled from a series of conversations, in Hollywood at the Sherwood Oaks Experimental College.

“I like to have all the musicians there at once,” explained Spector about his recording process. “I get everything on one track that I need. I put everything on 24 tracks just to see if it’s plugged in. The finished track never ends up on more than one track. I don’t wear a ‘Back To Mono’ button for no reason at all. I believe in it. I can make quad, it’s easy.

“I record in a strange way. I haven’t changed. I go from the basic track and put it onto 24. Then I have one track and 23 open. That’s the difference between having 24 filled or 19 filled. Which means, I can get 23 string players and overdub them 10 times and have 200 strings then I put them on one track. Do you know Ray Conniff uses more tape echo than I ever used in my life? That’s a fact.

“I record basic tracks and then put it all onto one track or maybe two. Then I condense. I put my voices on. The better the talent is around you, the better the people you have working with you, the more concerned., the better you’re gonna come off as a producer, like a teacher in a class.

“The musicians I have never outdo me. I’m not in competition with them. I’m in complete accord with them. You need the ability so you hire the best. I have the creativity. I know what I want.”

In a 1977 interview with me for Melody Maker Spector one afternoon, talked about employing singers on sessions.

"When you see a (Stanley) Kubrick movie you tell me how many names you immediately remember in the cast. One, two? It's the same with Fellini, and that's what I wanted to do when I directed a recording. Singers are instruments. They are tools to be worked with.

“My graduating theme [from Fairfax High School] was ‘Daring To Be Different.’ The moment I dared to, they called me different. I always thought I knew what the kids wanted to hear. They were frustrated, uptight. I would day no different from me when I was in school. I had a rebellious attitude. I was for the underdog. I was concerned that they were as misunderstood as I was.

“‘Then He Kissed Me’ [by the Crystals].’ That was an experimental record. “John (Lennon) told me the Beatles got the idea to use a 12-string guitar (that Barney Kessel played) from that record. But I thought it was too spaced out. I was against it coming out. I was gonna can it.

“It was very easy to work with John Lennon. There was no problem working with him. I think he is one of the greatest singers in music. I honestly believe that. I feel the same way about Paul (McCartney) as a singer. They are in a league with few others. I don’t feel the same way about George (Harrison) or Ringo (Starr). John and Paul are great rock and roll singers.”

Ken Scott first started engineering for the Beatles in the middle of their Magical Mystery Tour album and behind the board on the mix for “I Am The Walrus.” He then EQ'ed the master mix tape of “Hey Jude” and subsequently engineered the Beatles’ White album.

“I know one of my own original things going into engineering is that I wanted to be a backroom boy,” Scott reminisced to me in a 2011 interview.

“I didn’t have the confidence or the desire to sort of be in the public eye or to be known or anything like that. I know it was a conscious effort on my part to do it that way. When I was at school working with the drama society I didn’t want to be on stage. I wanted to be in the back helping to move everything along.

“Yes there were some blowups on the Beatles’ White album but not as many as people believe. There really weren’t. But the majority of the time it was fine.

“On that album George Harrison was really coming into his own. During that period they were laying down the tracks and playing together, sorting out the arrangements together. It was all good. Obviously whoever wrote the song had more sort of sway over ideas than the others did. It was very much a group effort.

“Generally speaking the others would filter out whilst whoever’s song it was worked on the finished thing. And it was like that for all of them. You knew that it would go a lot quicker with John than it would with Paul or George. Vocals would take the longest with Ringo. (laughs). Especially ‘Good Night.’

“It was pretty much the same for all of them. I think very much the difference, writing wise, for George, was that he was on his own. Even during the White album there were times when Paul and John would interact on how a song should be. But George didn’t have any of that. It was all him. And he didn’t initially have the confidence in his songs. Even at the White album stage. Yes, he was coming up with incredible stuff. He didn’t know it yet. He was writing more for other people,” volunteered Scott.

“If you think about it, he gave ‘My Sweet Lord’ away to Billy Preston. There was something he wanted to give away to Jackie Lomax. He didn’t have the confidence within himself to do those songs. Like ‘Not Guilty,’ even then, we never completed it. We never really got it to the point where it was even sort of even considered going on the album.

“And the fact that Trident had 16- track. There was a technical side to it as well. ‘I don’t want to work at Abbey Road studios. ‘I want to work with Ken…’ It wasn’t quite like that. It worked out very well for both of us I think,” added Ken.

“Like Abbey Road, the control room at Trident was still above the studio where we were looking down. So it was very much like Abbey Road number 2 studio in design. They were both great studios. There was something for me about number 2, the history of it. The whole thing. No matter how many times I go there I would stand at the top of those stairs and the hairs on the back of my neck would stand up. For me personally it has such a feeling. It’s amazing.

“Comparing the two studios… Trident was much more laid back. It was young people. It wasn’t the old people who ran Abbey Road. For musicians, Trident was a place to hang out. Whereas Abbey Road you only went in there when you had to kind of thing. Technically you could actually look at it like tape machine manufacturers. You got Studer. Who wouldn’t put in a tape machine 100 per cent up to their standards. That was Abbey Road. They wouldn’t put in any new gear in until it was 100 per cent up to their standards. So they got behind the curve.

“Whereas as Trident was more like every other tape machine manufacturer. They’d rush it out as fast as possible and to hell with the consequences. ‘We’ll fix it later.’ They would get in the latest gear and if something went wrong with it then they’d figure it out as it went along kind of thing.

“What did happen as long as it was of the only 8-track studio in London one even noticed, it was only when there was a second studio with 8-track that some people couldn’t book time at Trident. ‘Someone else is in there and we’ll take our tapes and go to studio number two and mix it there.’ They’d get it there and suddenly find out that all of the voices were squeaky.”

There is one other sonic factor informing All Things Must Pass as well as the entire recorded catalog of the Beatles at Abbey Road that can be traced to an important piece of equipment on the premises.

Richard Bosworth is a Beatles scholar and veteran music producer/engineer. During 2020 Bosworth produced and engineered a new album by Johnny Rivers at Capitol Studios in Hollywood.

In 1991 Bosworth oversaw a Hollies recording session at Abbey Road Studio and illuminates one reason why recordings by the Beatles, particularly their vocals, sounded so otherworldly since 1963. Bosworth points to an item engineers utilized capturing their vocals and group harmonies.

“Abbey Road had a unique wind screener pop filter closer to the microphone where certain sounds would become very powerful and actually collapse the microphone capsule, an EMT 140 plate with tube electronics. You could get the vocalist closer to the microphone and a more in-your-face sound. They came up with a metal windscreen that had two different screens and two different meshes on them and different physical angles, where the one metal mesh was rounded and one was flat.

“The patterns of the mesh were diagonal to each other, bolted tight onto the microphone, made with custom metal for Abbey Road. People started noticing quickly that moisture would get on the microphone capsule and you’d have to replace the capsule. Any pop filter changes anything to a certain extent. Unlike screen pop filters made out of foam, these were made out of metal and certainly not dampening high end. Those are unique. Trident was built in 1968 and had them as well.”

As far as the reason George Harrison titled his album All Things Must Pass, in a December 2000 interview with Billboard Editor-In-Chief Timothy White, Harrison disclosed the origins of the phrase “All Things Must Pass.”

“I think I got it from Richard Alpert/Baba Ram Dass, but I'm not sure. When you read of philosophy or spiritual things, it's a pretty widely used phrase. I wrote it after [the Band's 1968] Music From Big Pink album; when I heard that song in my head I always heard Levon Helm singing it!”

Richard Alpert (aka Ram Dass) was born in 1931. Alpert studied psychology, specializing in human motivation and personality development. He received an M.A. from Wesleyan and a Ph.D from Stanford. In 1967 he traveled to India, where he met his Guru and spiritual teacher, Neem Karoli Baba. Alpert studied yoga and meditation, and received the name Ram Dass, which means “servant of God.”

Ram Dass’ epochal book, Be Here Now is past a 34th printing with over 1.2 million sales.

In 1997 I interviewed Ram Dass about the Beatles.

“I loved The Beatles music. I took acid to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. I was real happy when Ravi Shankar started getting acceptance in the West, partly because of George Harrison going to India. I had heard of Ravi in the very early 60’s when I was in India. I played the tambora. I was delighted of the East-West merger.

“I was so much a part of bringing Eastern stuff to the West that it all seemed obvious to me when it eventually started happening here, so I don’t think I was blown away by the time it happened, I had already done it in my own being. It wasn’t like ‘Someone is doing this!’ It was great to see someone doing it with such style and class.

“Music is a vehicle for moving consciousness and humor is a vehicle for moving consciousness and the combination of that.”

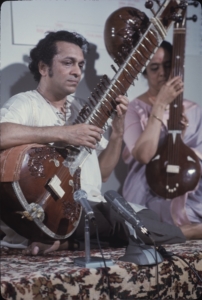

These are the directives and disciplines that Harrison first realized in 1966 when he first met Ravi Shankar. George had first heard the sitar in April 1965, on the set of the Beatles’ movie Help! Later in 1965, he would record with the instrument on John Lennon’s “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown).”

These are the directives and disciplines that Harrison first realized in 1966 when he first met Ravi Shankar. George had first heard the sitar in April 1965, on the set of the Beatles’ movie Help! Later in 1965, he would record with the instrument on John Lennon’s “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown).”

In September 1966, Harrison traveled to Bombay and became one of Shankar’s students. Subsequently, Harrison integrated the sitar into his own composition “Love You To” from The Beatles’ Revolver album, as well as fusing sitar and Indian influences on his selection “Within You Without You,” on the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album and also on “The Inner Light,” the B-side to the “Lady Madonna” single.

In 1997, I interviewed Harrison and Shankar in Southern California. Portions were first published in HITS magazine.

George Harrison was first introduced to sitar player and composer Ravi Shankar at a dinner party for the North London Asian Music Circle decades earlier.

“His music was the reason I wanted to meet him,” praised Harrison. “I liked it immediately, it intrigued me. I don’t know why I was so into it -- I heard it, I liked it, and I had a gut feeling that I would meet him. Eventually a man from the Asian Music Circle in London arranged a meeting between Ravi and myself. Our meeting has made all the difference in my life.”

Harrison commented on his own sitar playing.

“I’m not a very good one, I’m afraid. The sitar is an instrument I’ve loved for a long time. For three or four years I practiced on it every day. But it’s a very difficult instrument, and one that takes a toll on you physically. It even takes a year to just learn how to properly hold it. But I enjoyed playing it, even the punishing side of it, because it disciplined me so much, which was something I hadn’t really experienced to a great extent before.”

George went on to describe his earliest attempt at playing the sitar with the Beatles.

“Very rudimentary,” he revealed. “I didn’t know how to tune it properly, and it was a very cheap sitar to begin with. So ‘Norwegian Wood’ was very much an early experiment. By the time we recorded ‘Love You To’ I had made some strides.”

Harrison put his sitar experiments with the Beatles in perspective.

“That was the environment in the band, everybody was very open to bringing in new ideas. We were listening to all sorts of things, Stockhausen, avant-garde music, whatever, and most of it made its way onto our records.”

In March 1976 when I was a music reporter for Melody Maker, Harrison personally telephoned and arranged for me to attend a Ravi Shankar sound check and recital at The Roxy Theater in West Hollywood when George was proudly showcasing his Dark Horse Records/A&M label artist. We both witnessed Bob Marley & the Wailers at this venue in July 1975.

“He’s a very rare person...it is something so special,” Ravi Shankar reinforced to me in the 1997 interview I conducted.

“There are many other people who could do what George does, but they don’t have that depth. He’s so unusual. What has clicked between him and me, what he gets from me, and what I get from him, that love and that respect and understanding from music and everything, is really the most important thing. It’s not the money, or he helping me to record, that’s not the main thing. But it’s the very special bond between both of us.”

“I was introduced to Ravi through George,” revealed Dr. Deepak Chopra to me in a 1998 interview. “I grew up watching Ravi Shankar. Teenage years.

“In the ‘60s I was a fan of the Beatles. I bought Sgt. Pepper’s in India. I heard a lot of music on the BBC in India, and was brought up on classical sounds, Mozart, Vivaldi, Beethoven. Indian classical music, Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan and the Beatles.

“’Sgt. Pepper’s’ was the right thing at the right time. It was an interesting time. When people were kind of playing with drugs a little bit, the hallucinogenics, and causing some drastic mind-shifts in people.

“I was in medical school at the time Sgt. Pepper’s came out. A friend of mine actually had gone on a scholarship to England and brought back two copies of Sgt. Pepper’s, one for me and one for himself. And shortly after that the Beatles arrived in Rishakesh, India, in 1968. It’s interesting that George introduced me to a fellow Indian.

“In fact, I have known no one to have a talent for words as George has. He’s a great musician, but he’s an extraordinary lyricist, too. He’ll take a word and he’ll weave all kinds of meanings around that word. One of George’s greatest and most endearing qualities is his playfulness. It’s not like he’s in a hurry to get the project done. It doesn’t matter if it’s today, tomorrow, or five years from now. He’s playing with it. When you have that kind of relaxed awareness and relaxed attention, then there’s magic. I would say, of George more than anyone else, he’s detached from the outcome.

“I think the key thing is to not get caught up in your own self-importance,” cautioned Dr. Chopra, “as long as you can keep that in your awareness. In a sense just internalize the experience of gratitude that, for whatever reason, you happen to be part of a tidal wave, a phenomenon that is much bigger than yourself. And if your internal attitude is, ‘I’m grateful,’ everything has a beginning, a middle and an ending. And this will pass. I happen to be in the middle right now. Try not to take yourself seriously. Because once you start doing self-importance of any kind, it’s the biggest detriment to further creativity.”

Bobby Whitlock, along with Eric Clapton, sang background as the O’Hara Smith Singers, on the endearing and enduring All Things Must Pass.

Whitlock remained uncredited on the Harrison-recording dates, but provided pump organ, Electric Wurlitzer, Hammond organ, piano and tubular bells on specific tracks on the Harrison and Phil Spector production.

The Beatles’ Apple studio birthed the formation of Whitlock, Clapton, Carl Radle and Jim Gordon’s Derek and the Dominos band while participating on All Things Must Pass. In fact, Harrison supplied guitar overdubs to tracks done around their Spector-produced debut A-and-B side single, “Tell the Truth” and “Roll It Over.”

Multi-instrumentalist Whitlock is co-writer on several songs on Derek and the Dominos 1970 debut Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs.

In 2011 I interviewed Whitlock about the spiritual aspect of songs on both All Things Must Pass and Layla and Other Assorted love Songs.

“My philosophy is that it’s not mine in the first place. It’s not me doin’ it, you know. I’m that place where the creative principal of the universe operates. Just like Eric is that place through which the creative principal of the universe. Call it God, Holy Spirit. Whatever you want to call it, he’s that place with the guitar and I’m that place with my voice and my playing abilities and my songs. And the thing is that if the song, anything, comes by way that divine source, it will have longevity. It will live its own life.

“It comes from that divine source. You don’t have to worry about it. It is going to be a forever destination. It will be forever. Because you don’t have to worry about the money for it or if it is gonna be promoted right or anything. It will take care of itself.”

In November 2020 Universal Music Enterprises released 50TH anniversary deluxe edition of Derek and the Dominos’ Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs which includes the two tracks produced by Spector in 1970 that amounted to the first commercial outing by the short-lived group: “Tell the Truth” and “Roll It Over,” that was pulled from circulation by the group.

“When the Beatles started hanging out in Hollywood and Los Angeles with David Crosby, Peter Fonda, and the ‘Benedict Canyon’ type of people,” mused songwriter and record producer Kim Fowley in 2011, “George went a little further in 1969 began wishing he was in a band like Delaney & Bonnie & Friends, who became the blue print and the template for All Things Must Pass and The Concert for Bangladesh. Leon Russell, Carl Radle, Jim Keltner and Eric Clapton.

“Eric was more American emotionally than he ever was English. George was the most American of all the Beatles. He had been to America and St. Louis before the Beatles came to New York in 1964. George Harrison wrote ‘Blue Jay Way’ in the West Hollywood area. So he was the first Beatle to write a song about America.

“I saw Delaney & Bonnie open for Blind Faith in 1969 at the Inglewood Forum as the guest of Chris Blackwell to the show. I was the first white artist signed on Island Records,” Kim boasted. “The Trip’ came out on his Island label.

“I performed with both of them that night when they played the Forum. I had known Eric Clapton from England at the Richmond Athletic Club days when he was in the Yardbirds. And, I had met him again when Cream was forming. Then, at the Blind Faith show in the dressing room, Eric asked me to come on stage if I knew the words to ‘Sunshine Of Your Love.’

“Bonnie and I did a dance, during a matador version of ‘Sunshine of Your Love.’ When we entered the stage I yelled ‘Legalize Marijuana!’ I shouted it from the rooftops like Paul Jones in the movie Privilege. The hall turned off the sound. And everybody smiled and the band kept playing and the microphones were gone the music continued instrumentally and then Bonnie and I did the Alligator dance.

“Delaney & Bonnie were that kind of revolving door friendly Southern jam tradition. And in the final part of George’s life, the Traveling Wilburys. Who was in the Traveling Wilburys? Americans, along with him and Jeff Lynne. So that was an extension of The Concert For Bangla Desh and an extension of Delaney & Bonnie. Remember what Delaney & Bonnie’s single was? ‘Are You a Beatle or a Rolling Stone?’ So there was that connection.

“Delaney & Bonnie were that kind of revolving door friendly Southern jam tradition. And in the final part of George’s life, the Traveling Wilburys. Who was in the Traveling Wilburys? Americans, along with him and Jeff Lynne. So that was an extension of The Concert For Bangla Desh and an extension of Delaney & Bonnie. Remember what Delaney & Bonnie’s single was? ‘Are You a Beatle or a Rolling Stone?’ So there was that connection.

“Remember what Jerry Wexler said, ‘The best rock ‘n’ roll is part black gospel, part jazz, part country and then whatever the Hillbilly’s brought which wasn’t country. Because that’s a southern tradition you don’t get out of Los Angeles or New York,” proclaimed Fowley.

“I knew Billy Preston from the very early 1960s. He was a child protégé for SAR Records, which was Sam Cooke-owned and they went to the same lawyer I did. Walter E. Hurst. He was around the office signing contracts. He infused gospel into All Things Must Pass and The Concert For Bangla Desh.

“Ringo is God drummer. He’s on ‘My Sweet Lord,’ a number one song in the world. ‘Don’t Come Easy’ is good. He was a great drummer because he knew what to leave out. Kim Fowley hates cymbals. And Ringo didn’t mess up the guitar frequency with an overuse of cymbals.

“Ringo is God drummer. He’s on ‘My Sweet Lord,’ a number one song in the world. ‘Don’t Come Easy’ is good. He was a great drummer because he knew what to leave out. Kim Fowley hates cymbals. And Ringo didn’t mess up the guitar frequency with an overuse of cymbals.

“George’s solo album debut and the subsequent Concert for Bangladesh symbolizes a pan-national version of Mad Dogs & Englishmen,” presents Fowley, “and if go back to that point that is another extension of Delaney & Bonnie and Friends. It was George Harrison thinking of himself possibly in a telethon context. George saw that idea and he took it to the next level, because he was a Beatle who could think.”

Delaney & Bonnie’s 1969 debut LP, Accept No Substitute made a big impression on both George Harrison and Eric Clapton. A&R man and producer David Anderle had discovered this white soul outfit gigging in West L.A. and brought them to Elektra Records to supervise their memorable album produced by Delaney Bramlett.

Billy Mundi and Jeff Simmons, during their Frank Zappa and Mothers of Invention employ auditioned for the band as well as Duane Allman. George Harrison had tried to sign Delaney & Bonnie to Apple Records in the U.K.

In 2006 and 2014 I interviewed longtime friend, drummer and percussionist Jim Keltner. We discussed his dear friend George Harrison and his stint with Delaney & Bonnie and Friends over dinner one evening.

“We were doing a whole new soul thing that wasn’t Stax,” offered Keltner.

“We cut it at Elektra Studios on La Cienega. Leon Russell and Delaney Bramlett gave me a lot of confidence that I could play rock ’n’ roll, coming from jazz. And I was with my good friends Bobby Keys (sax player) and Carl Radle (bass player). Bonnie wasn’t doing Janis Joplin or Tina Turner. She was doing more of a hillbilly, gospel, blue-eyed soul kind of thing.

“In October of 1968 I got a call to sub for Jimmy Karstein at Snoopy’s Opera House, a little club in the valley with Delaney and Bonnie. At the time I was recording with Gabor Szabo and playing gigs with him at places like Shelly’s Manne-Hole in Hollywood and The Light House in Hermosa Beach. Then in February ’69 they asked me to do Delaney and Bonnie’s Accept No Substitute album at Elektra.

“Leon played piano on everything but ‘When This Battle Is Over,’ which was Dr. John, Mac Rebbenack. It was a song Mac wrote with Jesse Hill. There was a fusion of the Southern people beginning to play with the Hollywood cats. Everyone at the time was being influenced by that scene.

“George Harrison loved the Delaney & Bonnie LP when he heard an advance acetate of it and tried to get it on Apple Records. Delaney and Bonnie had tremendous magic and chemistry. I was playing with Delaney & Bonnie at Thee Experience club on Sunset and Jimi Hendrix came in two different nights to jam with us.

“Leon and Delaney gave me a lot of confidence that I could play rock and roll coming from jazz,” Keltner stressed. “And I was with my great buddy, Carl Radle, who I had been in Gary Lewis and the Playboys with. No demos or rehearsals, we went in and cut it. And Bobby Keys on sax. Leon’s piano playing on the ‘The Ghetto’ is the greatest. No one else can do that.

“Jim Gordon later replaced me. When I got to know John (Lennon) he told me he liked the Delaney & Bonnie and Friends Accept No Substitute album,” recalled Keltner.

I asked Jim about Harrison’s guitar playing and Ringo on the drums.

“Well, literally, every guitar player I’ve ever played with pays homage to George because they know what it’s like to be the guy to be the guy coming up with the parts, that’s the second most important voice in the song, aside from the singer’s voice is the lead guitar, the way he frames the voice and how he plays the extra melody around the melody and stuff, the way he handles all those chores. That’s a special gift when you’re able to do that.

“George was probably one of the greatest that ever did that ever. Scotty Moore and Carl Perkins were his heroes. George was not what you’d call an improviser. He was such a songwriter type of guitar player that he saw the guitar part as a piece constructed in his head and he would do it and he would construct it as he went along and came up with these brilliant parts that will live forever. I mean, any Beatles’ record you pick up you’ll see that.

“All Things Must Pass. Incredible. Jimmy Gordon and Ringo played great on the record. Ringo is one of rock’s all-time great drummers. All you have to do is listen to the Beatles records, of course, especially, the Live at the BBC. Rock and roll drumming doesn’t get any better than that. Earl Palmer, Hal Blaine, Gary Chester, Fred Below, David ‘Panama’ Francis, great early rock and R&B drummers, and Ringo fit right in there with those guys. Listen to the BBC tapes and you’ll hear what I’m saying.

“Klaus Voorman was the principal bass player on the Concert For Bangladesh. Phil loved the way Klaus played. He had a great way of stretching the time. Klaus is one of the greatest bass players I’ve ever played with. His playing was always just exactly right for the song. He didn’t have that much in the way of chops but he made up for that with his great musical sense.”

Keltner worked on the Spector-produced John Lennon Imagine album, “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” and Lennon’s Rock and Roll LP. Jim also appears on George Harrison’s Living In A Material World.

“I was staying at Eric Clapton’s and the phone rang early one morning I picked it up since I was the only one awake. It was Phil Spector. He asked if I wanted to come down and play. So I said ‘sure.’ I borrowed a drum set from Colin Allen who was in a band, Stone the Crows. We became good friends and he helped me out a lot in those days.

“The first song we did that night was ‘Jealous Guy.’ George (Harrison) was there as well. We did ‘Don’t Want To Be A Soldier’ next.

“Playing on ‘Jealous Guy’ was one of those moments when you feel you are in a dream, especially later during playback in a room with John, Yoko, George, Phil Spector, and Klaus Voorman listening.

“George later called and said, ‘Let’s do a single.’ So we went in to Wally Heider’s studio 4 on Cahuenga in Hollywood and did ‘Bangla Desh’ with George and Phil Spector. Leon played and I think he helped arrange the song. The birth of the concert sort of started with this single. I loved the song.”

Heider’s studio was where Clapton and Harrison in 1968 had cut the instrumental tracks with engineer Bill Halverson for Cream’s “Badge.”

“I read these things about George being kind of anti-celebrity and all that. I guess he had enough of that with the Beatles, ya know, so that the Bangladesh event seemed like a warm and wonderful cause that everyone turned out for. And that August,” continued Keltner, “we all did the two Bangladesh charity shows in New York.

“The [August 1971] Bangladesh concerts were a great little reunion,” enthused Keltner. “They loved playing with Ringo and me. Klaus Voorman was the principal bass player on Bangladesh. And it spawned a great live album set that George and Phil put together.

“George was absolutely focused and fantastic as a leader. Of course he had Leon (Russell) in his band. And Leon helped with the arranging and all. I remember that everything seemed to be fine at the sound check and that I didn’t have too many concerns. When we started playing with the audience in the room it really did come alive. George seemed very powerful that night.”

In March 1973, the Harrison and Spector-produced Concert for Bangladesh by George Harrison & Friends triple-disc set won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year of 1972.

To mark the 30th anniversary of All Things Must Pass, Harrison supervised a remastered edition of the album, which was issued in January 2001, less than a year before his death from cancer at the age of 58.

This configuration implemented five bonus tracks including two Spector-supervised songs “Beware of Darkness” and “Let It Down” done at Abbey Road.

On the disc A Conversation With George Harrison February 15, 2001, George further described the All Things Must Pass recording, and working with Phil Spector on the production of his post-Beatles' solo outing.

"Well in those days it was like the reverb was kind of used a bit more than what I would do now. In fact, I don't use reverb at all. I can't stand it. But at the time I did the record with Phil Spector and we did it like Phil Spector would do it. You know it's hard to go back to anything 30 years later and expect it to be how you would want it now. I'd dare say if I did a record today, in 30 years I'd probably want to change it. That's the only thing about the production. It was done in cinemascope and it had a lot of reverb on it to what I would use now, but that's how it was and at that time I really liked it."

The last time I saw George Harrison was in 1998 one afternoon in a home of a mutual friend in Los Angeles. When I arrived, Harrison greeted me with, “Well, at least here you don’t have to take your shoes off like at Ravi’s house!”

Harrison had come by to review tapes in the home studio at the residence. George had seen Eddie Izzard’s show at The Tiffany Theater and offered a good recommendation of a local Indian restaurant in West Hollywood he frequented, Taste of India. He had just dined there with his wife Olivia and Jim Capaldi. A fellow Pisces, and according to his sister Louise, Harrison and I share the same February 26th birthday. I had my 50th birthday at Taste of India. When we split I gave him some freeway directions to his in-laws residence in the South Bay area.

Over the last few decades, Harrison and Shankar would, on occasion, visit Self Realization Fellowship in Encinitas, California, the beach community near San Diego where Shankar lived with his second wife Sukanya since 1992.

The windmill chapel at the Lake Shrine in Pacific Palisades California carries on Paramahansa Yogananda’s spiritual and humanitarian Self Realization Fellowship work and hosted George Harrison's funeral service in 2001.

“I am now talking about a brother in the past tense,” sighed Jim Keltner in 2001. “George was a very important teacher to me at that time. Georgie. My friend and my beautiful and wonderful brother…

“But the thing is, George has been prepared for this for a long time. Just listen to his songs, for instance, he wrote and sang ‘The Art of Dying’ over 30 years ago. He’s been extremely prepared for this. It’s us who weren’t prepared. So we flounder around looking for words to try and describe him and flounder around deal with not ever hearing his voice again, ya know.

“What a voice he had, too. What a beautiful voice he had. What a tremendous speaking voice and a singing voice.”

When Harrison left the physical world, in mid-March, 2001 for MOJO magazine I asked Phil Spector to comment about his work with John Lennon and George Harrison.

When Harrison left the physical world, in mid-March, 2001 for MOJO magazine I asked Phil Spector to comment about his work with John Lennon and George Harrison.

"First of all, let me say, that in 1970, George Harrison and John Lennon re-entered my life, left footprints on my heart, after which I was never the same. I treasured both their friendships, and my only hope was that they both would live forever, for I preferred a world with George and John in it. Tragically, we have lost John, but his loving memory will be etched in my heart forever.

“I could never put, in this small space, many of the truly wonderful stories I love to tell about my adventures with George and John over the period of time we worked together, nor could I fully explain the impact the both of them have had on me, and how much they enriched my life. They were both the quintessential friends, and they truly made this World a better place to listen in.

“In closing, let me just add that while both George, John, and I had lengthy and distinguished careers before we started working together in 1970, I believe that the years the three of us did work together were the most creative of our careers, and these memories and the Art we made stand out, to me, as probably the most significant and meaningful, as well as the most creative part of my life. I treasure those memories, and because of that, anytime George would like to make another historical recording masterpiece and album, I would be only too willing to produce it with him. I love George, and his brilliant mind and talent; I always have, and I always will."

“Listening right now to the 2001 CD release of All Things Must Pass, I pronounce myself impressed all over again,” declared Dr. James Cushing.

“The album’s blend of an epic Phil Spector orchestral sweep and the intimacy of Harrison’s voice is the key to the album’s paradox, and why the music holds up (mostly) after half a century, because it’s as big as the Beatles ever wanted to be, bigger than Shea Stadium, while it’s also George taking you aside and speaking to you privately about important matters. George turned 27 in February 1970, the year the album was recorded, and for a man that age to have put these forces together into one package and gotten it to the top of the charts is enough for undisputed Classic Rock Hall of Fame status.

“My only reservations involve 1) the influence of ‘Hey Jude’ on some of the tracks, whose endings just go on too long. ‘Isn’t It a Pity’ on vinyl side one is not the only example. Some editing / tightening of playing time would not have hurt anything. 2) The last two cuts on the vinyl Side Four, ‘Isn’t It a Pity — Version Two’ and ‘Hear Me Lord,’ have always sounded like filler to me, as though they had 70mins but needed 80. 3) Just as ‘A Day in the Life,’ ‘All You Need Is Love,’ ‘Goodnight,’ ‘The End,’ and ‘Get Back’ were all inevitably right last cuts on their respective Beatles albums, ‘All Things Must Pass’ ought to have been the last track on this! The whole album is leading up to it, and the songs that follow are overshadowed. This is especially true on the CD edition, where the sexy ‘I Dig Love’ comes jarringly right after ‘All Things Must Pass,” underlined Cushing.

“I also want to stand up for ‘Apple Jam,’ which I enjoyed enormously over Xmas 1970 and I’m enjoying almost as much right now.

“Three of the four long jams are built around the Delaney and the Dominos rhythm section of Jim Gordon, Carl Radle, and Bobby Whitlock, who keep the grooves going as well as they did for Derek. Dave Mason, EC, and GH are the guitarists on ‘Thanks for the Pepperoni’ and ‘Plug Me In’ (this jam lasting only 3:17). Two horns and a second keyboard are added to this lineup on “Out of the Blue,” which doesn’t quite earn its eleven minute playing time. The fourth jam, ‘I Remember Jeep,’ is just fine: Ginger Baker on drums, Klaus Voorman on bass, Billy Preston on piano, EC sounding especially inspired on guitar, and GH beeping and whooshing on his Moog.

“Its best moments of guitar/drum rub recall Cream. I say ‘almost’ because I hadn’t yet heard much electric jazz then — no Larry Coryell, no Tony Williams Lifetime, no Herbie Mann with Sonny Sharrock, no In a Silent Way or Bitches Brew — so I had nothing to compare it to.

“My estimation of this music changed radically after hearing the Mahavishnu Orchestra in early 1972. Nevertheless, I insist that the rock ’n’ roll dance beat of ‘Thanks for the Pepperoni’ is still a gas, and I’m glad they included it.”

“The very first thing I can recall about All Things Must Pass was it cost me (actually, truth be told, it cost my dear grandmother) a whopping $7.99 Canadian! ...and that was still after Sam the Record Man's gigantic in-store, pre-Xmas deep deep discount," recalls frugal-as-ever shopper Gary Pig Gold.

"And even though Capitol/Apple's enticing shrink wrap sticker boasted '3 LP's For The Price Of 2 Including Full Color Poster' – the 'free' LP being Side 5 and 6's Apple Jam ...and no, I doubt I played it more than once either – that big 23-by-35-inch image of George stayed stuck to the inside of my bedroom door clear through the arrival of the Imagine album's Tittenhurst piano-white poster, causing many over thirty in my household to repeatedly exclaim 'Oh my, who is that scary looking old man??'

"All domestic aesthetics aside, ATMP was in fact the first Box Set to proudly become part of my collection, and each Harrisong's pretty holier-than-me lyric reprinted upon its dust sleeves point quite directly towards the similarly boxed vinyl Jesus Christ Superstar due just a little later, if I may draw such a parallel. But when all was said and sung, strictly secularly speaking this great big George box remains every bit as weighty – literally, historically and socio-musically today as it did as 1970 became '71 ...while the man's fellow ex-Fabs were still busy crooning about getting on yer feet and entering the streets, taking a morning bath and wetting hair, and not shouting or leaping about may I remind everyone.

"The deceptively Quiet Beatle did indeed have a LOT boxed up to get off his chest and onto tape after at least a half-decade of being, as he most revealingly explained to Dick Cavett at the time, 'subtly sat upon' by Messrs. Lennon, McCartney and Martin.

“As a result the melodies were absolutely astounding, the chords beneath surprisingly serpentine, and as noted the lyrical sentiments were much more often than not perceptive, profound, and deeply penetrating to the extreme. All the better then to be sonically supported by Phil Spector's equally sweeping Wall of Sounds; wholly suitable productions which today remain even more unique and, yes, spectacular ...especially when A/B'd against those comparatively anemic mixes on the re-issued album's 30th anniversary bonus material.

“Thank God, or Whomsoever, George resisted, as I quote his 2001 threat of, 'remixing every track to liberate the songs from the big production that seemed appropriate at the time but now seems over the top.' Really, George? May I just say those gorgeous, big productions tower proudly over what could have been diluted via, for example, your pal Jeff Lynne ...perish the very thought.

"Now it could be argued by some, myself included, that George never again approached the pomp or majesty of All Things Must Pass (perhaps he shouldn't have used up all his best material on his first post-split release?) and along with – for entirely different rhymes and reasons of course – John Lennon's Plastic Ono Band it remains one of the special few long-players that can still stand loudly and proudly alongside... oh, say, Rubber Soul, Revolver, or even Beatles VI.

“Yes, it was in 1970 the sound and sentiment of a man, and musician, demonstrating among many other things just how sweet life can be by setting oneself free. And it all still sounds every single bit as lustrous and liberating – not to mention unquestionably box-worthy – as 2020 now becomes 2021. Let it continue to roll into the night."

In 1974 George Harrison gave a press conference in Beverly Hills at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel that I attended when he was preparing for a U.S. solo tour. George was pelted with many questions about the Beatles, his Dark Horse record label and the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

I published the results in the November 2, 1974 issue of Melody Maker.

On meeting the Beatles Harrison responded, “Biggest break in my career was getting into the Beatles. In retrospect, biggest break since then was getting out of them.”

Was he ever amazed about how much the Beatles still mean to people?

“Not really. I mean it’s nice. I realize the Beatles did fill a space in the sixties. All the people the Beatles meant something too have grown up. It’s like anything you grow up with you get attached to things.

“I understand the Beatles in many ways did nice things and it’s appreciated the people still like them. They want to hold on to something. People are afraid of change. You can’t live in the past.

“Since I made All Things Must Pass, it was nice for me to be able to play with other musicians. I don’t think the Beatles were that good. Ringo has the best backbeat I’ve ever heard. Him and Levon Helm of the Band were the best drummers I’ve ever heard. They don’t play technically, no drum solos, just play.

“Ringo will play a great backbeat 24 hours a day. Paul is a fine bass player, he’s a bit overwhelming at times. John has gone through his scene, to tell you the truth, I’d join a band with John Lennon any day, but I couldn’t join a band with Paul McCartney. That’s not personal, but from a musical point of view. John’s new record is lovely.”

Harrison was asked about his concepts and goals of Dark Horse Records.

“There isn’t really a concept or goal. The goal in life is to manifest our divinity. Because each one of us is potentially divine. All we can do is try and do that, and hope that influences our work.”

In addition at that frenzied media event, Harrison referenced the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and his visit to Indian with the Beatles in 1967.

“I have a lot of respect for him. He gave me help and plugged me in to a method of being able to contact that reservoir of energy which is within us all. Pure consciousness. I experienced it. He showed me how to reach that. Everything else is just words, beyond the intellect is to have an experience you have to have in order to know.”

Reporters wanted to know how George saw the role of entertainer in working with causes and charities?

“I don’t think it’s an entertainer’s job. He does what he can. And I do it through music. It’s not isolated to musicians.”

In his 1974 Beverly Hills-based press conference, Harrison itemized the charities he would be working with on his tour that year including, “a concert in Los Angeles for the Self Realization Fellowship. It was founded by Paramahansa Yogananda. He happened to be a big influence in my life. I’d like to repay his in a small way.”

"George may have always been the Quiet One," recalls lifelong Beatlemaniac Gary Pig Gold, "but today I think he would be called instead the Deep Beatle. Always grinning that sly, close-to-the-turtleneck smile, let's remember he always had just the right solo and diminished chord for the proceedings, plus was the first to fly highest when the Fabs splintered. Free as a bird.

"It's just no surprise then that such a kindred musical spirit as Ravi Shankar recognized this deep blueness within George Harrison, and duly approached him when his country called. Of course George being George, he put his guitar where most would put only their money, and when he made his own calls, all answered.

“Eric, Billy, Leon, Ringo, and even blue-jeaned Bob to name but the obvious. The Concert for Bangla Desh made that first big helping splash, proving that rock 'n' roll trumped mere governments. And the world may not necessarily be a better place for it today, but it's definitely a wiser one.

"Of course George himself was ALWAYS wise. And his heart was always as large as the spirit it carried, then and now. After all, isn't it usually the Quiet ones you have to watch??"

“I don’t think there has been a more influential Guitarist to me than George Harrison,” guitarist Steve Lukather of Toto emailed me in 2020. “HE was the on switch to my ears being glued to ' that sound.’ Plus he looked so cool like they all did.

“I was bitten by Beatles fever like everyone else my age, 63 now, and it never stopped. Had you told then told me I would have worked with 3 of them and That Ringo would be a close friend in life... I would have said ‘Yeah and the first man on Venus as well.’

“George's compositions always stood out as he had his own style. All The Beatles did, but All Things Must Pass was HIS record filled with songs he may have held back and or was not allowed to flush out. I don’t know I wasn't there. He told me many wonderful stories cause I KNOW which songs He played on and Paul and John and I have studied those records like the Holy Grail.

“A wonderful side bar is I was honored enough to meet him in 1992 and we had a great but short great friendship. He gave me a signed copy of Paramahansa Yoganadna’s Autobiography of a Yogi.

“I heard ' Free as a Bird' before it came out. He jammed with us at the Jeff Porcaro tribute in '92 and I never thought he would show up! He did and he was so kind to me.. I could write so much more.... but there is a LOT of deep soul music in those grooves. ‘What is Life’ is a fave. SO many.

“The jam sides are fun too but Georges songs were way ahead of his time. Like he was...

God Bless George and his family, also wonderful people.”

“In 2002, my two oldest and closest childhood friends both lost their dads,” lamented author Lonn M. Friend in a 2020 correspondence.

“We grew up together in the San Fernando Valley, discovered music via the Beatles in the 60s and came of age as our rock n’ roll imaginations flowered in the 70s. When I arrived for each of their pop’s funerals at the same local hillside mortuary, I had the same condolence gift in my hand. George Harrison All Things Must Pass Remastered. 2 CD box set US Capitol 2001. Made sense.

“We grieve best through the yarns of our youth. ‘Beware of Darkness,’ ‘My Sweet Lord,’ ‘Isn’t it a Pity?’ and the apocryphal title track fit the ceremony in message and mood. Melodic psalms for the fond farewell; insight before the last flight; all things must pass, all things must pass away. Did the Rabbi really say it or was I projecting? Can’t argue with that spiritual logic.

“Beatle George the Taoist mystic, the six string seeker, found his ephemeral groove while the world was still healing from the death of the most fabulous foursome pop culture ever knew. Both elders left behind loving wives. ‘What is a life without your love? Tell me who am I without you by my side?’ Handfuls of dirt cast atop lower caskets. Moment of prayer, moment of melody.

“My dad is 91, still playing piano, commands and recalls at an instant a most eclectic and venerable cache of classics from across the decades. He plays ‘Something.’ George was in love - within and without - with everything. Can I get a ‘Wah-Wah?’”

On Friday, November 26, 2011, All Things Must Pass, the 40th anniversary edition, was released in a limited edition, numbered 180-gram vinyl set in its original 3LP configuration, with faithfully replicated original monochromic album art, poster and lift-top box packaging. Newly remastered at Abbey Road Studios from the original analogue master tapes,

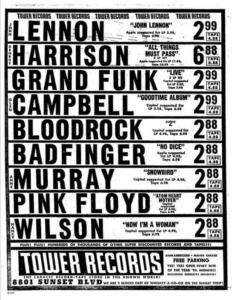

All Things Must Pass is a 2015 documentary film directed by Colin Hanks exploring the saga of Tower Records.

Established in 1960, Tower Records was once a retail powerhouse with two hundred stores, in thirty countries, on five continents. From humble beginnings in a small-town drugstore in Sacramento, California, Tower Records eventually became the heart and soul of the music world, and a powerful force in the music industry.

Hanks’ movie investigates this iconic company's explosive trajectory, tragic demise, and legacy forged by its rebellious Sacramento, California-born founder, Russ Solomon.

All Things Must Pass is essential viewing for anyone who ever found sound in a record store. It’s a cautionary celluloid tale from filmmaker Hanks.

In my 2020 book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, I interviewed Colin and asked about the source of his movie title, the George Harrison master recording that runs over the end screen credits, and his licensing request of that Harrison and Spector production.

“All Things Must Pass was not always the title of the film. At the very early stages and I was trying to make it, I obviously had an idea of what I wanted the story to be. I didn’t really know what the theme was. I was asked, ‘So what’s like the theme of the film?’ I still didn’t have an answer for that. I talked a little about this in the Kickstarter video. But I went up to Sacramento on a lark and decided to drive by the old Tower store which was still there and in tack. And that sign was still up. The All Things Must Pass Thanks Sacramento. And I just went, ‘Oh My Gosh! That’s the theme.’

“Even the best parties have to end. And all things must pass. So that was really, for lack of a better phrase, that was a pretty obvious sign of what this thing needed to be called. And obviously it made perfect sense thematically. I really liked the fact it was a store employee that put that sign up. I thought there was some poetry in that. And, obviously, I wanted to do everything I could to use the song. But I’m also cognizant of the fact very respectful of the fact that that song is personal to George. And has a very deep meaning. And, so I’m very fortunate that I’ve met Olivia on numerous occasions and that I met George once a long time ago. He was an incredibly kind man.

“I sent her the film and said, ‘I would really like to be able to call this movie All Things Must Pass. I’d really like to be able to use the song. But know you have final say on this and you can not hurt my feelings in anyway shape or form. We’d be really honored if you let us do this.’

“We sent her the film. She came back to me after a weekend. ‘I’ve watched it twice. I love it. I can’t believe this story. What an incredible story. Yes. Absolutely. Go right ahead.’”

(Harvey Kubernik in his journey encountered the four Beatles. He is the author of 19 books, including It Was Fifty Years Ago Today: The Beatles Invade America and Hollywood, Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For summer 2021 they have written a multi-narrative book on Jimi Hendrix for the publisher.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in July 2020 has published Harvey’s 508-page book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring Harvey’s interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, Robby Krieger, John Densmore, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among many others.

In 2020 Harvey served as Consultant on Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time documentary directed by Alison Ellwood. It debuted on the EPIX/MGM television channel.

Kubernik’s writings are published in book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

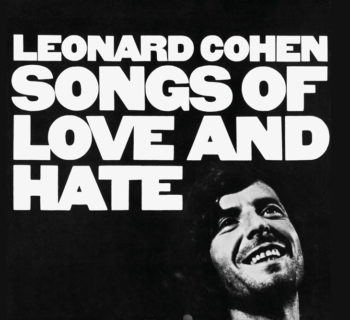

Harvey penned a back cover endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada published in October 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years)

Album cover Courtesy of Universal Music EnterprisesPhotos of Ringo Starr and George Harrison by Henry DiltzArtifacts Courtesy of Gary Pig Gold Archives