The '68 Comeback Special (at the time titled Singer Presents…ELVIS) originally aired on December 3, 1968 and was a pivotal broadcast event that upped-the-ante on Elvis' career, the evolution of pop culture and the history of television.

Elvis Presley entered 1968, that heartbreaking year, as barely a blip on the radar screen of a generation wallowing in a purple haze. Luxuriating high above Sunset Blvd. in Trousdale Estates, he gave little thought to the kandy-colored hordes marching up and down the neon Strip content to placate his remaining fans with star turns in such disposable drive-in fare as Clambake. Presley was still issuing movie soundtrack albums but garnering nowhere near the sales figures of a smash hit like Blue Hawaii.

In 1968, Steve Binder conceived, directed, and produced ELVIS, The ‘68 Comeback Special. TV Guide called this landmark event “the second greatest musical moment in television history next to the Beatles' debut on the Ed Sullivan Show.” Engineer and record producer Bones Howe was Binder’s partner in the Presley endeavor.

While Col. Tom Parker Presley’s manager continued to lobby for a traditional “Christmas” show, Presley bonded with Binder and Howe, who he had worked with in Hollywood years earlier.

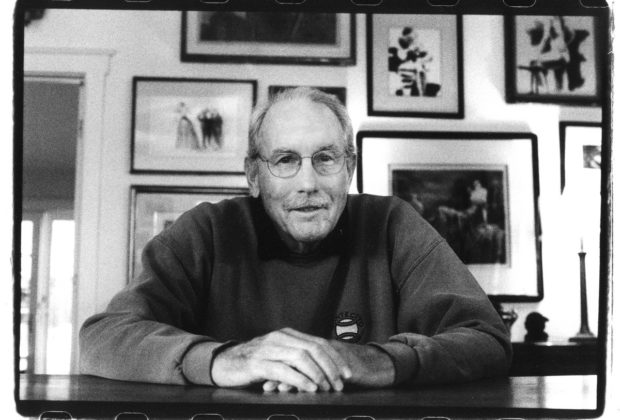

Dayton “Bones” Howe, a soft-spoken, jazz-loving, Southern gentleman, came to Los Angeles from Georgia in 1956. He quickly settled his rail-thin frame (hence, the nickname) behind the mixing console at Radio Recorders Studio, serving under principal engineer Thorne Nogar on some the young Presley’s breakthrough hits.

Over the next decade, Howe became one of the most celebrated engineers in the music industry, working on albums by Ornette Coleman, Jack Kerouac and Lenny Bruce as well as recording a parade of Top Ten singles from Timi Yuro, The Mamas & Papas, and Johnny Rivers. Howe then produced The Association, The Turtles, The Monkees, and The 5th Dimension. The West Coast sound was as much a product of his panoramic vision as it was the worship of cars, girls and warm summer breezes. In this collaboration with Binder, Bones Howe was poised to take on his greatest challenge.

“The first time I saw him was at the Florida Theater in Sarasota, Florida when I was in high school. He was a young country singer. He performed between movies,” remembered Howe in a 2008 interview we conducted for my book Turn Up The Radio! Roc, Pop and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972 published by Santa Monica Press.

“I first did some work with Elvis in late 1956 and early ’57 in Hollywood at Radio Recorders. He drove out from Tennessee in a stretch Cadillac with DJ and Scotty with the gear in the back seat. They became out to record with Steve Sholes, the A&R guy who was responsible for signing them on to RCA Records. He brought them to Hollywood to record them. RCA was doing all their recording in those days at Radio Recorders. I did some session with Thorne Nogar. Thorny was very good to me and took me under his arm. I was a recordist and he asked me to do some sessions with Elvis. Elvis could never get his name right so he called him Stoney.

“In Hollywood I saw Elvis with his buddies. It was the first time anyone ever heard of block booking a studio for a month. We never had to tear it down. We could leave the studio at night. I worked on ‘All Shook Up.’ Elvis never stopped moving in the studio. He recorded everything live. In those days you didn’t separate people so everyone was in the same room. Direct to mono when we started. The two-track that we did on Elvis had his voice on one track and everybody else on the other track. When we started with Elvis there was no stereo. He could sing a ballad. He could imitate anybody. Mention a singer and he would imitate them. ‘Fats Domino.’ You would turn your back and you thought Fats was in the room. Elvis would come in with Hill & Range music publishers and Elvis would record only their songs.

“The Colonel never showed up or came to the studio. Maybe once to get some paper signed. Elvis ran the session and Steve Sholes ran the clock. ‘OK Elvis. That’s 2:14.’ ‘Sounded good in here. Want to listen?’

“The sound at Radio Recorders. It was the wonderful echo chamber in Studio B. A live chamber in those days. Not tape reverb. The same one I used on big band sessions in that room. It’s also the way we recorded at Radio Recorders. I watched Elvis become a huge star.”

When studio owner and sound innovator Bill Putnam came to Hollywood from Chicago in 1957, his initial competition in town was Radio Recorders, which he had attempted to purchase. As United Recording was being developed and built, Putnam and producers in Hollywood often did early rock ’n’ roll bookings for labels like Dot, Mercury, Liberty, Imperial, and Colpix at Master Recorders, the Bunny Robyn-owned studio on 535 North Fairfax.

By 1958, Studio B at United was complete, with two reverb chambers, a mix-down room, and mastering rooms, one of which had stereo. By 1960, the Ventures were recording in Hollywood, and their instrumental sounds were enhanced by the echo chamber as well. In 1961, Putnam bought Don Blake’s Western Recorders, located next door on Sunset Boulevard. Engineers Bones Howe and Wally Heider came to United, followed by Chuck Britz, Lanky Lindstrot, and Lee Hirschberg.

“When Bill bought Western, he walked me down the street to see the building. Studio 3 was in the building, and Chuck Britz was an engineer there and remained there after Bill bought the building.

“When Putnam opened his studio, the first thing he did was that he got a new Grampian cutting head [that] you could pump a lot of volume into. You could really pump a lot of voltage and signal into it, and it would cut a much hotter 45 than the Altec head that everybody else used for cutting LPs and 45s. UREI was the development company, and a different division of United Recording. They developed a 1176 limiter, which I ran and did all the test runs on. He had a prototype, and gave it to me in the studio to use. United just became the place to record. Randy Wood of Dot Records worked exclusively at Studio B at Radio.

“Elvis was in the makeup chair,” Bones Howe reflected, “and said, ‘you know, it’s been a long time since I’ve been in front of a live audience. When I went out there I didn’t know if they were gonna laugh at me. I really didn’t know.’ He was frightened. He starts singing and he has them all in his hand.

“When we started the ’68 Special, you got to remember Elvis was on his ass. We didn’t know how it was gonna turn out. We didn’t know if it would work or not. We had a lot of confidence in Elvis. He came to every dance rehearsal,” emphasized Howe.

“Steve and I went through five weeks of editing,” offered Bones. “We had to figure out how to put all this stuff together. Because it ended up not being linear. Steve had this idea of using the ‘in the round’ as the narration for the thing and we plugged all the other stuff into that it would work. We cut an hour and a half special which NBC refused to air owing partially to the ‘bedroom’ or ‘Bordello’ scene.

“We then did a 60-minute version eventually. We edited it on Vine Street. You cut it like a home movie and then give that to the video tape editor. And in those days the video tape editor cuts the video tape. They peel the audio off onto a film track and then they cut that to match the thing and then they put it back on.

“Actually, you are two generations down. We begged them to cut to video tape because of the sound quality, but they wouldn’t do it. There wasn’t anything lost because it was mono anyway. It lost some of the top end and some of the low end like you do. Bill Cole was a really good audio guy. He understood that we were gonna use the double system and that they were gonna shoot us down. He had done this before. And he got the sound on there and it survived the generation down and the generation back. In those days they all thought it all goes on a four-inch speaker on the side of a TV set.”

“There was a big discussion about the closing song,” underlined Binder, about the bold decision to have ‘If I Can Dream’ as the finale. One of the songs Elvis wanted to close the show with was a Frankie Laine number, ‘Because.’ Col. Parker wanted ‘I’ll Be Home For Christmas.’”

Binder and Howe demanded something topical and penetrating. 1968 had suddenly erupted in political and social conflict. And the musicians were not immune to the ramifications.

“I felt strongly that Elvis would be a great deliverer of a peace and love message,” Binder reiterated. ‘If I Can Dream’ captured that sentiment perfectly. We used two Elvis vocal tracks of the song. One was for a single, and the other cut later in the week at the soundstage was inserted in the show. Earl Brown was a choral director on The Carol Burnett Show and was in the music group, the Skylarks on RCA. And I think this was a song that, like a lot of people who write just one great novel. I don’t think Earle realized what he wrote, and having Elvis Presley perform it was the miracle of all miracles.

“I felt strongly by Elvis singing ‘peace and love’ after all these 1968 assassinations it just seemed like the perfect song to say these words, And I think Elvis was a great deliverer of that message. Billy Goldenberg did the arrangement overnight and Elvis did five takes on the vocal.”

The success of the '68 Special reignited Presley's career in a major way. Shortly after the special aired, Elvis entered American Sound Studio in Memphis for the sessions that included the Mark James-written cautionary tale "Suspicious Minds," and his country-soul masterpiece From Elvis In Memphis (which included the chart-topping "In The Ghetto").

1969 saw Elvis’ return to live performance with a record-breaking engagement at The International Hotel in Las Vegas, kick starting a regular run of live shows that lasted for the rest of his career.

The success of the '68 Special reignited Presley's career in a major way. Shortly after the special aired, Elvis entered American Sound Studio in Memphis for the sessions that included the Mark James-written cautionary tale "Suspicious Minds," and his country-soul masterpiece From Elvis In Memphis (which included the chart-topping "In The Ghetto").

In summer 1970 Presley did his headline engagement at the Hilton Hotel. He was backed by his core band and the Sweet Inspirations under the direction of musical director Joe Guercio and his Orchestra. By October, Presley was back at the #1 position on the hit parade with “Suspicious Minds.”

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows published in 2014 and Neil Young Heart of Gold during 2015. Kubernik also authored 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In2021 the duo collaborated on Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. In 2004 Harvey wrote Hollywood Shack Job: Rock Music In Film and on Your Screen published by the University of New Mexico Press

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey penned liner note booklets to the CD releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

In 2020, Harvey served as a consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood that debuted on the M-G-M/EPIX cable television channel. During December 2021, Kubernik was an interview subject and a consultant on a documentary, The Toronto Rock and Roll Revival, produced at Varsity Stadium September 13, 1969 in Canada, featuring the debut of the John Lennon and Yoko Ono Plastic Ono Band. Klaus Voorman, Geddy Lee of Rush, Alice Cooper, Shep Gordon, Rodney Bingenheimer, promoter John Brower, and Robby Krieger of the Doors were filmed by director Ron Chapman. Pennebaker Hegedus Films is exec producing. It’s scheduled for a late spring 2022 theatrical release.