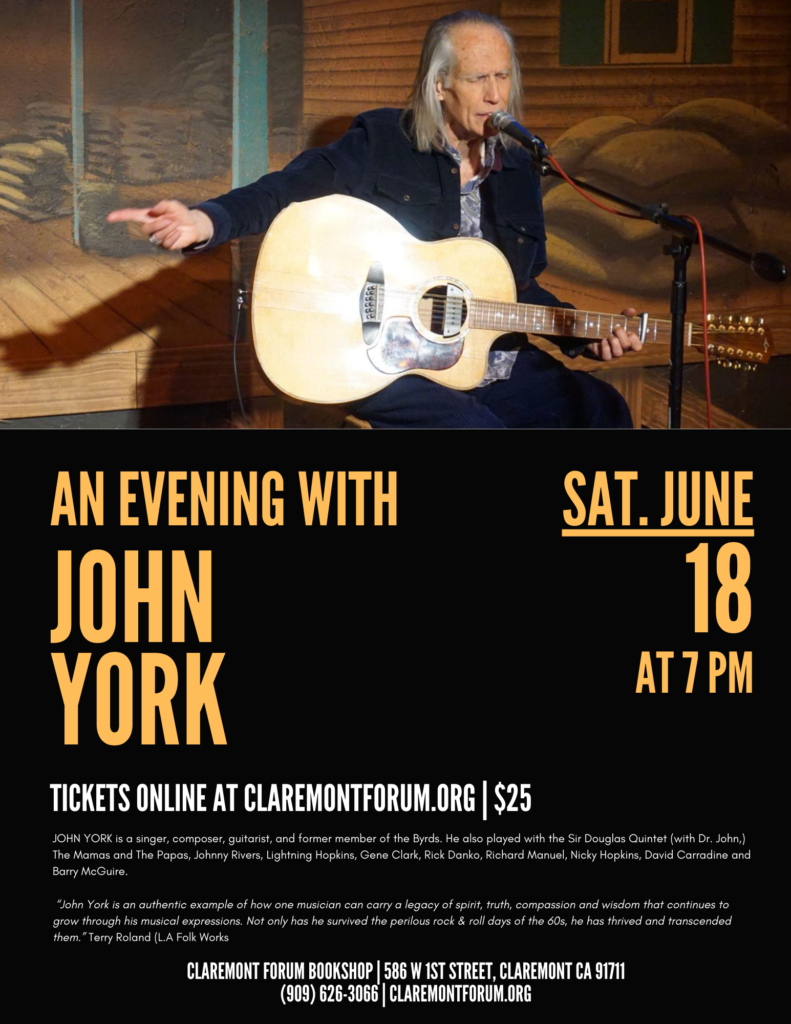

An Evening with John York will be held in Claremont, California at the Claremont Forum on Saturday, June 18th for a special concert/fundraiser for the Prison Literary Project.

Born in White Plains, New York, York, in the mid-sixties, joined a folk-rock band the Bees, who issued three singles. In September 1968 he replaced the Byrds’ bassist Chris Hillman in the Byrds. At the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival, York was the bass player in the Mamas & Papas touring band and recorded with them in 1968.

“After Sweetheart of the Rodeo, Chris left, Clarence (White) came along, finally we got (bassist) John York, Skip Battin, Gene Parsons and it was a country rock band,” explained Roger McGuinn in a 2007 interview we conducted. “That was the last incarnation of The Byrds.” The outfit appeared on the television series Playboy After Dark in 1968. You can watch the group doing Bob Dylan’s “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” and “This Wheel’s On Fire.”

Over the subsequent decades, guitarist and bassist York honed his craft on stage and in the studio with the Bee Gees, Sir Douglas Quintet, Chris Darrow, and Johnny Rivers, among others. In 2008, York teamed up with singer/songwriter Barry McGuire of “Eve of the Destruction” fame for Trippin’ the 60’s, a collaboration that toured for eight years.

John York’s studio credits include albums with Moby Grape’s Peter Lewis – Peter Lewis (1995), multi-instrumentalist Chris Darrow – Coyote + Straight from the Heart (1997), Chris Darrow and Max Buda – Harem Girl (1998), and guitar wizard Toulouse Engelhardt and percussionist Remi Kabaka – A Child's Guide to Einstein (2004). For decades he has performed in the Southern California region and in Japan.

“John York is probably the most undervalued -- a fine R&B informed bassist and strong harmony singer, who brought plenty to the Byrds’ table,” emphasized Melbourne, Australian-based journalist and author, Michael MacDonald.

“He introduced the Byrds to Pamela Polland's ‘Tulsa County Blue,’ which became an album track on Ballad Of Easy Rider. His R&B roots became apparent on an unreleased version of Pentangle's ‘Way Behind The Sun.’ (York handled lead vocals) and his own composition ‘Fido’ allowed Gene Parsons a drum solo. Post Byrds, York has been one of the more adventurous ex-Byrd members -- his eclecticism has taken him into Native American music, Japanese sounds, middle Eastern music, folk rock and a wonderful music/spoken word album with Kim Fowley. No surprise, too, that York became a friend and collaborator with another SoCal eclectic, Chris Darrow. John York is still out there writing, performing and recording -- a proud artist who refuses to let his wheels spin."

In 2019 I interviewed John York for the book Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child, written by my brother Kenneth and I, published by Sterling/Barnes and Noble. We discussed his work and gigs with the Byrds and Jimi Hendrix.

“Bob Dylan had a big impact on all of us: Jimi, Roger McGuinn and myself. The Ballad of Easy Rider we did in Hollywood at Columbia studios on Sunset Blvd. Terry Melcher produced it. We had been involved in an earlier movie Candy. Dylan had promised Peter Fonda he would write a song and wrote some lyrics on a napkin. Roger wrote. Dylan’s name is not on the tune. We were curious in a very healthy way. I remember when we cut the song, I played the cello part on Roger’s Moog synthesizer.

“When we played the song for Clive Davis, he heard it and said it was ‘too short.’ Not long enough for the end of the film. And, of course, he was right. We had never heard a ‘money guy’ talk like this. If you listen closely the first verse is spliced on at the end. The movie and the soundtrack supported each other and were popular. I never did the song live until I went to Japan because I knew the biggest record by the Byrds was, and still is, ‘Ballad of Easy Rider.’ 15 years year ago people would yell it out at gigs. I continue to mine that treasure trove of sixties music. I do an all-Dylan show. I do a show that is called the 3 B’s: Byrds, Beatles and Band. I find that people get tremendous hope from this music.”

York shared live concert venues with Jimi Hendrix. He reminisced about the man and his music.

“I had a ‘Jimi Hendrix Day’ in my life…I was playing bass for the Mamas & Papas in summer of 1967, including an August ’67 concert at the Hollywood Bowl. John Phillips, God bless him, had Jimi open the show. There was a middle act of a Beethoven string quartet. The drummer was Eddie Hoh and the guitar player was Eric “Doctor” Hord in the Mamas and Papas. We all were at the sound check in Hollywood on a beautiful summer’s day. What struck me was that Jimi was a very shy guy. Everything he had to do at the check was very gentlemanly. Every way he went he would be followed by half a dozen hippie chicks. If he was standing on one side of the stage they would go sit over there. And if he had to get up and go over to the other side of the stage, they would all of them would stand up and go follow him there. They would never say anything and sort of competing with each other. We all got a kick out of that.

“In the evening, Denny Doherty and I walked to the very back of the Hollywood Bowl. To look down over the audience and can see the stage. All of a sudden Jimi went into his first song ‘Wild Thing.’ ‘Wow! What is this?’ He starts playing single notes that are so loud and so clear that it is heaven in the air. It was like you could see the notes hanging in the air. ‘Holy shit!’

“So, Denny and I went down immediately to the stage area, we had all access passes so we were able to go to the edge of the stage. And they had these tall trees on planters that were on wheels. One on each side. In one moment when the lights went dark between songs we ran up on stage and hid behind one of these trees. So, we were literally just a few yards from Jimi, Mitch [Mitchell] and Noel [Redding]. We stayed there for the whole set. We had never seen or heard anything like it. An amazing thing to experience. ‘Cause it was so early on nobody was jaded about this guy.

“His rhythm section was completely amazing. Each one was highly innovative and playing the way they wanted to play. I don’t know the dynamic of the band was. Or that if he told them to play anything in particular. The drummer obviously came from a jazz background. The bassist was a converted guitarist. In a trio that worked. Because there was no other guitar player. I mean, it was kind of the way Skip Battin played with the Byrds. Skip gave you a lot of information and it was going against the way bass players were supposed to play. Bass players were supposed to be almost invisible. Both those guys impressed me. The thing about it was that they were able to give Jimi what he needed. In order for him to float those notes, right? He needed these two guys who could make the background bubble and boil. They were on it every moment. They weren’t kicking back, being cool and letting him do everything. They were just churning under him so he was able to do whatever he needed to do without the energy dropping at all. It was remarkable. And at the time, 1967, this is new. And very creative. The thing that touches me the deepest about Jimi is his guitar playing. A level of artistry that he was able to reach that was overwhelming.

“The night of the Hollywood Bowl there was a big party at John and Michelle Phillips’ house in Bel-Air. The old Jeanette MacDonald mansion. I had been there before. It was a party filled with people. There was a pool table and Jimi was sitting right next to me. Gradually people started speaking to Jimi.

"In June the Byrds played the Newport ’69 Devonshire Downs festival. Jimi jammed in a surprise later at the event. [Guitarist] Clarence White was in the band then. That day Clarence and Jimi were on the same stage. They had a very unique connection and that they both found their own language. They both had listened to what had been done before and they knew there was another way they wanted to do it. There was no disrespect for what had gone before because you could hear their influences. You could hear where Jimi came from. You could hear where Clarence came from.

“But they had their own language. They found a way to make a new way for what we thought the electric guitar could do. Both of those guys said, ‘Did you know it could do this?’ Both gave us a feeling that ‘I may be the only one who knows what can be done with this instrument. Listen to this.’ And, of course, they both have thousands of imitators. When you heard them, it was an extension of the musical vocabulary. This is like new territory. But they were guys who had done the work and research. They were dedicated.

“I did an eight-year gig with Barry McGuire and he was up at Denny Doherty’s house in Laurel Canyon in the late sixties. And Jimi came for the weekend. And he stayed and wore his guitar. Never took it off. Fell asleep with it. For three days. Jimi and Clarence put in countless hours of time with their instrument. And they become the instrument and the instrument becomes them. And that is what you first encounter when you hear music on that level.

“As for Jimi, it’s really worth getting into his music. There seems to be stuff that is more accessible and other stuff that you sort of have to let grow on you. He’s worth it. If it’s deep you’re not gonna get it all right away. As for the reissues, packages, my theory on the continued popularity of the sixties rock music and recording artists. One is that you get something from that music that you can’t get anywhere else. It’s like a unique river. A certain river of music. And that’s it. And each generation there are people who hear it and go ‘More of that. That’s cool!’ There’s something there you can’t get anywhere else.

“The other thing is the cult of personality. The people who just can’t get enough celebrity worship. You got a machine behind somebody whose impact is undeniable. And they die at the right time. Man, that is an endless cash cow if you know how to sell that. You have something that really is worthwhile becoming more and more of a commodity.”

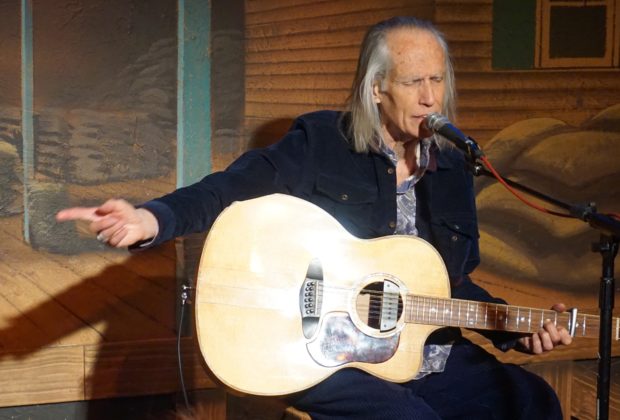

Photo by Sumi Foley

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 they wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, David Leaf, Dick Clark, Curtis Hanson and Michael Lindsay-Hogg.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, including, The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey wrote the liner notes to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

In 2020, Harvey served as a consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood that debuted on the M-G-M/EPIX cable television channel. During 2021, Kubernik was an on-screen interview subject and consultant for the rock & roll revival music documentary about the Toronto Canada 1969 festival at Varsity Stadium spotlighting the debut of the John Lennon and Yoko Ono Plastic Ono Band and an appearance by the Doors. Klaus Voorman, Geddy Lee of Rush, Alice Cooper, Shep Gordon, Rodney Bingenheimer, John Brower, and Robby Krieger of the Doors were interviewed by director Ron Chapman. A summer 2022 theatrical release.