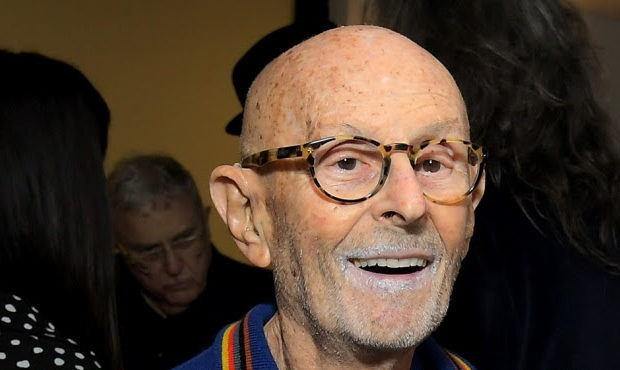

Over the decades I had a handful of encounters with Mo Ostin. A fellow Fairfax High School graduate. If you went to Fairfax High School you have a melodic bond with other graduates. He was pleased I became an A&R man for MCA Records and delighted I was very instrumental in pairing Tom Petty and engineer Jimmy Iovine for "Damn the Torpedoes" for the label. I produced an instructional and educational basketball audio endeavor with the legendary UCLA (ret.) basketball Coach, John R. Wooden. Mo Ostin endowed the Mo Ostin Basketball Center, a comprehensive basketball practice facility near Pauley Pavillion on the Westwood, Ca. campus. My last chat with Mo was around eight or ten years ago at a Burt Bacharach book event at the Crossroads School. We briefly discussed Norman Granz and Verve Records.

Russ Regan | record executive “At the time I was general manager of Loma Records, the Warner Bros. R&B label. Joe Smith brought me to Warner Bros. Kim Fowley had praised Jimi to us. I had an office next to Mo Ostin.

“In 1965, AM radio station KHJ in Hollywood changed their format to Boss Radio. I loved the RKO radio programmer, Bill Drake. Play the hits. Keep the talk down to a minimum. He understood the repetition of Top 30.

“In ’67 I noticed the growing development of the LP away from the 45 rpm. FM radio really starts in 1967. My friend, deejay Dave Diamond, was really doing some wild and different programming on the AM dial with KBLA 1965–1967 after he left KHJ in 1966.

“Around April ’67, Mo Ostin called me into his office and played me the acetate of ‘Hey Joe’ by the Jimi Hendrix Experience. ‘Listen to this!’ And then puts on ‘Purple Haze,’ and I said, ‘It’s either gonna be huge or nothing. There’s no halfway on this.’”

Kim Fowley: I was signed to Reprise Records as this kind of cult act by Warner/Reprise head Mo Ostin. And then Mo told me one day that my records weren’t selling. ‘What else do you do?’ ‘I think.’ ‘OK. Give me a thought so I don’t cut you off because I’m paying your bills.’ ‘Cause I was getting advances. ‘Sign my neighbor, Jimi Hendrix.’ ‘Why?’ ‘Because he’s the Chuck Berry of the ‘60s.’ ‘What does that mean?’ ‘It means that white people will buy him. Black people don’t buy Chuck Berry and black people won’t buy Jimi Hendrix. But a ‘60s Chuck Berry would sell records to white people.’

“I had all the phone numbers and gave them to Mo since I met Hendrix the first time in 1966. I produced the Soft Machine previously in England, who like Jimi Hendrix, were managed by Michael Jeffreys, who also had the Animals at the time. In 1966 I was his neighbor in England in Bayswater.

“In our first 45 minute meeting in the hotel lobby, I was literally the first person Hendrix met when he got off the plane from New York, we talked music, and he said he wanted to play science-fiction rock ‘roll.

“Jimi liked the fact that I knew about the Spanish Castle venue in the Seattle area. I was the promo man for ‘Tall Cool One’ by the Wailers from his neighborhood, since I was tall and cool. I was a producer of L.A. based Richard Berry, who wrote ‘Louie, Louie,’ who wrote ‘Half Love Will Travel,’ that were regional hits, And Jimi knew them. I produced a single on Richard Berry.

“I told Mo about Jimi and that it would be a good idea to sign Hendrix to the label for North America. Then a half-hour later, Brian Jones and Jack Nitzsche visited Mo in Burbank. ‘Brian and Jack. I have a question. Who is Jimi Hendrix and should I sign him? I have inside information.’

“And Brian turned to him, and said, ‘Look, I like you as a guy. But I respect you as a record man if you’d sign someone like that and make him famous in this country. Because people like me would want to be on this label.’

“And that was when the concept was born of a Warner/Reprise using as one artist to attract a whole tribe of artists to a label that was artist friendly as opposed to capitalistic authority freaks.

“Brian and Jack confirmed what I said. We all knew that Jimi would be great acquisition for the label in America. “Mo Ostin subsequently visited me in LA at the House For Homeless Groups, which was LWG Studios, where I was living in a back room. He arrived in a Cadillac. “Later, after Jimi signed to the Reprise/Warner Bros., label, Mike Jeffery came by as well, who was very thankful for my help. “I connected him with Buddy Walters, who was doing the light show for the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band. Buddy then set up the light show for Jeffrey’s clients Jimi Hendrix and the New Animals with Eric Burdon.

“In the early ‘70s I was at a record music event in Hollywood one night with Alice Cooper at The American Legion Hall on Highland Ave. Up the street from TTG Studios. Mo Ostin was there and came up to Alice and I. Alice greeted Mo and said, ‘Do you know my friend Kim Fowley?’ And Mo responded, ‘Kim Fowley introduced me to rock ‘n’ roll.’

“I wrote a song for Alice, ‘Elected’ on his ‘Billion Dollar Babies’ album. I know Alice and his original band were just nominated in late September to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Denny Bruce | record producer, A&R manager “In early spring ’67, [musician and record producer] Jack Nitzsche and I were living at the Sunset Marquis Hotel in West Hollywood. We were between pads. Jack got an advance copy of ‘Hey Joe’ and it blew his mind. “Jack knew Mo Ostin at Reprise very well and did ‘The Lonely Surfer’ for the label and all sorts of arranging and producing in the early sixties. And then Jack got the advance first Hendrix album in mono. It sounded better, with more punch to it, than what Warner/Reprise put out later in stereo.”

Joe Smith | former president, Warner Bros. Records “Hendrix became an acquisition for us in North America. I took out the first Hendrix album to our independent distributors during summer ’67, and I would make the pitch. And I’m in Chicago with all our distributors from the Midwest and the South. And I said, ‘This is the music that will change the world. Now, you’ve been listening to Frank Sinatra and Sammy Davis Jr. records here. This is what we’re going to be dealing with for many years.’

“And our deal used to be with our distributors that they bought seven and they got one free. And then I looked at the order from Minneapolis and they ordered seven records. I called them in. ‘This is the future!’ And I added three zeroes. ‘You just bought seven thousand of this fuckin’ album and you’ll get a thousand free.’ You had to convince these older guys who grew up with Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra records.”