Motown’s 60th Anniversary celebration is in full swing, with a host of special commemorative initiatives taking place throughout the year.

'Motown: The Complete No. 1’s' box set

Motown: The Complete No. 1’s box set. - Courtesy photo

Over the last 60 years the label garnered 180 No. 1 hit songs worldwide.

Motown/UMe is planning a newly-expanded edition of the collectible Motown: The Complete No. 1’s box set. The special 11-CD and digital anniversary edition will be released worldwide on June 28.

Motown: The Complete No. 1’s features 208 chart-topping Motown hits in one must-have 11-CD boxset and digital compilation. Showcasing the iconic American label’s universal cultural significance, Motown: The Complete No. 1’s includes U.S. and international charts chart-topping entries: The Four Tops’ "I Can’t Help Myself," Marvin Gaye’s "What’s Going On," the Jackson 5’s "ABC," Martha & the Vandellas’ "Dancing In The Street," the Marvelettes’ "Please Mr. Postman," Diana Ross’ "Ain’t No Mountain High Enough," Smokey Robinson & the Miracles’ "I Second That Emotion," the Supremes’ "Where Did Our Love Go," the Temptations’ "Ain’t Too Proud To Beg" and Stevie Wonder’s "Signed, Sealed, Delivered (I’m Yours)" are assembled in the collection.

“I learned how to play bass from Motown for Christ sakes! I learned how to play different type of roots on certain chords,” admitted Brian Wilson in an interview with me for his 2007 Pet Sounds tour program.

A Universal Music media announcement further details the upcoming retail product.

“Motown: The Complete No. 1’s includes: 10 bonus tracks across its first 10 discs – all Motown hits that had cover versions by other artists that went to No. 1, from David Bowie and Mick Jagger’s chart-topping turn on Martha & the Vandellas’ "Dancing In The Street" to Coolio feat. L.V.’s re-working of Stevie Wonder’s original "Pastime Paradise" for the smash hit "Gangsta’s Paradise." The package’s newly-added Disc 11 contains six more Motown No. 1’s, including two that were not included in the set’s original release and two Diana Ross remixes that have more recently topped the Billboard Dance/Club chart: "Ain't No Mountain High Enough (2017 Remix)" and "I'm Coming Out/Upside Down (2018 Mix)."

“Motown: The Complete No. 1’s is housed in a lovely replica of Motown’s original Hitsville U.S.A. headquarters in Detroit, Michigan (now home to the Motown Museum), the box set also includes an exclusive 100-page book with rare and vintage photos, detailed track annotations, and an introduction by Smokey Robinson, who is himself responsible for 20 Motown No. 1’s, both with his group The Miracles and as a solo artist.”

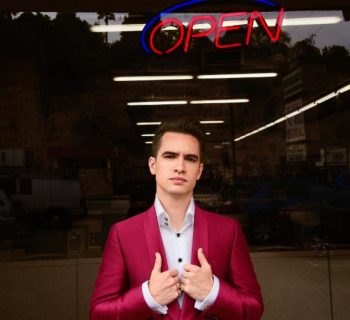

'Motown: The Sound of Young America' Exhibition

The Temptations. - Courtesy photo

On April 13, the LBJ Presidential Library in Austin, Texas opened a new exhibition, "Motown: The Sound of Young America." Curated by the Grammy Museum, the exhibition traces the evolution of the label, focusing on its legendary artists and musical achievements, and explores how the sound of Motown continues to influence some of pop music’s most important artists today.

This is the first time many of the exhibition’s artifacts have been seen in in a museum setting.

Performances of the acclaimed new musical Ain’t Too Proud – The Life and Times of The Temptations began in February at Broadway’s Imperial Theatre.

UMe and the show’s producers are preparing the Ain’t Too Proud Original Broadway Cast Recording that UMe will issue this spring.

Ain’t Too Proud will play Broadway’s legendary Imperial Theatre (249 West 45th Street). This new musical that follows the Temptations' journey from the streets of Detroit to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

With their signature dance moves and unmistakable harmonies, the outfit rose to the top of the charts, creating an amazing 42 Top Ten hits with 14 reaching Number One. This revealing story of brotherhood, family, loyalty and betrayal is set to the beat of the group's treasured hits, including "My Girl," "Just My Imagination," "Get Ready," "Papa Was a Rolling Stone" and so many more.

After breaking house records at Berkeley Rep, The Kennedy Center, CTG’s Ahmanson Theatre, and Toronto’s Princess of Wales Theatre, Ain't Too Proud, written by three-time Obie Award winner and MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant recipient Dominique Morisseau (Pipeline, Skeleton Crew), directed by two-time Tony Award winner Des McAnuff (Jersey Boys), and featuring choreography by Tony nominee Sergio Trujillo (Jersey Boys, On Your Feet), now brings the untold story of this legendary quintet to irresistible life on Broadway.

Fifty-five years ago, the Temptations released their first Motown album, 1964’s Meet The Temptations. For nearly 60 years, The Temptations have reigned as one of popular music’s most beloved and successful groups worldwide, lauded by Billboard in 2017 as the Number One R&B Artist of All Time.

Multi-instrumentalist Al Kooper’s 2005 solo album Black Coffee has a remake of "Get Ready," a song Smokey Robinson first composed for the Temptations.

“I’ve cut probably three other Smokey Robinson tunes over my career. He’s special,” Kooper offered in a 2010 interview.

I asked Al if he saw the influence of Robinson’s songwriting on Bob Dylan. I did.

“One of my favorite things is when I called Dylan one day and said, ‘Hey…What are you doing?’ ‘Eating a piece of toast and listening to Smokey Robinson...’ So, that makes a lot of sense.”

I had witnessed some of the mid-1960s Motown Revue live road shows in Los Angeles and Hollywood and danced on a couple of music TV shows when the Motown acts would be booked on the Sam Riddle-hosted 9th Street Weston Melrose Avenue and Dick Clark’s American Bandstand Vine Street location.

My brother Kenny and I went to the KHJ Second Annual Appreciation Concert at the Hollywood Bowl on April 29, 1967, for the United Negro College Fund and the UCLA School of Music, headlined by the Supremes with Buffalo Springfield, the Seeds, Brenda Holloway, Johnny Rivers and the Fifth Dimension.

In 1966, I saw the Temptations on Shindig! at the ABC-TV studios on Prospect Avenue. They sang a live vocal on "My Girl," mixed with a pre-recorded music track. They were clad in matching powder blue outfits in front of me.

That was living color even though the series was broadcast in black and white.

In February of 1976, I interviewed Temptation David Ruffin in Hollywood for a profile in the now defunct Melody Maker.

“The Temptations were individuals who happened to sing together,” Ruffin explained to me. “I never regretted any of the songs we did and even the choreography on stage has been widely copied. I liked the dancin’ part of that group. Then you couldn’t just stand there and sing. The audience was moving and you just reflected what was goin’ on. If anything, I’d like my association with the Temptations to be remembered as that we gave something. We helped young artists get in a position.”

Ruffin then pointed out to me, even during the chart success of "My Girl," only 10 years earlier, he and the Temptations were subjected to unfair restaurant incidents during tours and many situations that at times were shocking.

“We went through a few mindbenders. Some cats had to buy us food ‘cos restaurants wouldn’t serve us, mostly in the south. Things are much better today but I can think of the times when I was driving independently of the group in my Cadillac and the police didn’t like black people with money or any fame, made me get out of town. They wouldn’t even let me stay overnight.

“I was visiting my mother once time. Parked the car outside and the cop said, ‘you can’t park it here.’ I knew why he didn’t allow me to stay with mama.

“Yet the musicians and later on all kinds of kids went to our shows. We would rap and sing on the bus ride between concerts and it was a lot of fun.”

Soul music legend Bobby Womack knew Ruffin from when they were teenagers.

During a 2009 dinner interview I had with Bobby, he passionately acknowledged David’s performance with the Temptations at The Trip nightclub on Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood in 1966 as well as Ruffin’s role on his own musical journey.

“David Ruffin of the Temptations and I were very close, from years ago when we were singing Gospel as teenagers, and they had this big talent show in Detroit with the Staple Singers and the Womack Brothers. And David was singing with a group Ollie and the Nightingales out of Memphis. He was only 13. But he had so much charisma. When he walked on stage…30 years later we talked about it, ‘Man, you took that trophy from me.’

“I would follow Ruffin around. To make a long story short, he became the Temptations and the Temptations became David Ruffin. He would always treat me the same way but he’d add, ‘these guys don’t understand our relationship. They don’t know how long we’ve known each other.’ Then I became friends with all of them.”

“David blew minds in Hollywood at The Trip nightclub, and he was a guy I said, ‘I’m gonna learn something if I can. What is it?’”

Their legendary 1966 Trip stint was also attended by music producer and artist manager, Denny Bruce who, in 1965 and ’66 played drums with Frank Zappa as the Mothers of Invention were being formed.

“The Rising Sons with Taj Mahal opened the show,” reminisced Bruce. “There was an intermission and then David Ruffin makes his way through the crowd, gets in his place with the group, which had a hydra-headed microphone stand with 4 or 5 mics.

“The next song is one he where he doesn't sing lead until maybe the second verse. "It’s Growing" or maybe "You’re My Everything." Ruffin does a spin move and grabs a mike and is singing, all in the one move. Women screamed! The group gets a lift from this and really shows their strength in harmonies, and showmanship.

“The Temptations did carry their own master of ceremonies. And he now has a microphone and is preaching about ‘the love shown by David, who was too ill only hours ago to even hold down food. But his love for his brothers, and the audience he loves here, to let anybody down! Ladies and gentlemen, show this young man some love with a big round of applause!”

In November of 1974 for Melody Maker, I interviewed Bobby Rogers, a member of the marvelous Miracles, since their inception in 1958, when he joined up with his sister Claudette, Ronnie White, Pete Moore, and William Smokey Robinson.

Rogers, who shared the exact Feb. 19, 1940 date of birth as Smokey Robinson in the same Detroit hospital, co-wrote a number of compositions with Robinson: "The Way You Do the Things You Do" for the Temptations, "First I Look at the Purse" cut by the Contours and the Miracles’ "Going to a Go-Go."

“The Miracles have always to this point been a singles-orientated group. Smokey was writing for the group and everybody else. Smokey never really had the opportunity to do a concept thing. The best thing that ever happened to music has got to be the What's Going On album by Marvin Gaye. Marvin was listening to everything that was around. Beatles, Stones, pop, and jazz.

“You know that Sgt. Pepper LP? It was always on Marvin's turntable. Marvin took some time off and really looked at what was happening. Society has changed. A long time ago black people were smoking dope and if they got caught they would go to jail. Now, white people are doing it and they bring the penalty down. Also, we had some racial hassles years ago in the South, and it's getting better now,” praised Bobby.

“I really loved touring with the English groups, back in 1963 and 1964. We used to tour with the Rolling Stones and people like Georgie Fame. During the breaks from touring, a lot of the groups would ask questions about certain songs on our albums. I remember when we filmed The TAMI Show Mick Jagger asked me about what I'd thought of the album James Brown Live At The Apollo, which was his favorite LP.

“One time on a tour he mentioned that he'd like to record a Marvin Gaye song for the next Stones album. A month later, Hitch Hike was being played all over Detroit radio.

"Man, those early tours were a trip. Endless hours of bus rides and all these skinny English dudes asking us about the Tamla Motown sound. I never realized how important or influential we were on groups like the Beatles and Stones. He said his name was George and he was in a group named the Beatles. We used to party with all the groups, and have become good friends. You know, music travels in sort of a cycle. The early days were beautiful. We dug all the people we played with. Back in 1965 my favorite song was 'Get Off My Cloud.'"

The visionary record executive Russ Regan, who signed Neil Diamond and Elton John to UNI/MCA Records, and Barry White to the 20thCentury record label, once worked for Berry Gordy at Motown and later for their Jobete Music publishing division on the West Coast.

“The first record I promoted was 'Please Mr. Postman' by the Marvelettes in 1961,” recalled Regan in a 2016 interview.

“I also worked with the Supremes, the Miracles, and Marvin Gaye. Believe it or not, Marvin Gaye had moments of greatness on stage or he could be lousy. And I’ll tell you why. He really didn’t like performing. It was a job to him. It can’t be a job for a performer. People don’t realize this. You can’t be up there thinking you are working,” Russ suggested.

“Barry Gordy, Jr. used to come to town. He taught me about hooks in songs. And that people buy records because they have to love them, not like them. There used to be record hops at high schools. One time at Jefferson High school I took Marvin Gaye in Watts. He had never been out there before. The girls attacked him. He lost one shoe of his penny loafers. We went to Fairfax High School. Groups played in the auditorium. I was taught a lot about the record business by Berry Gordy, Jr.

“I became a promotion man during 1961-1964. I learned the value of a song and the hooks of a song. Every Motown hit has hooks in it. It starts with the opening. You can always smell the opening of a Motown record.”

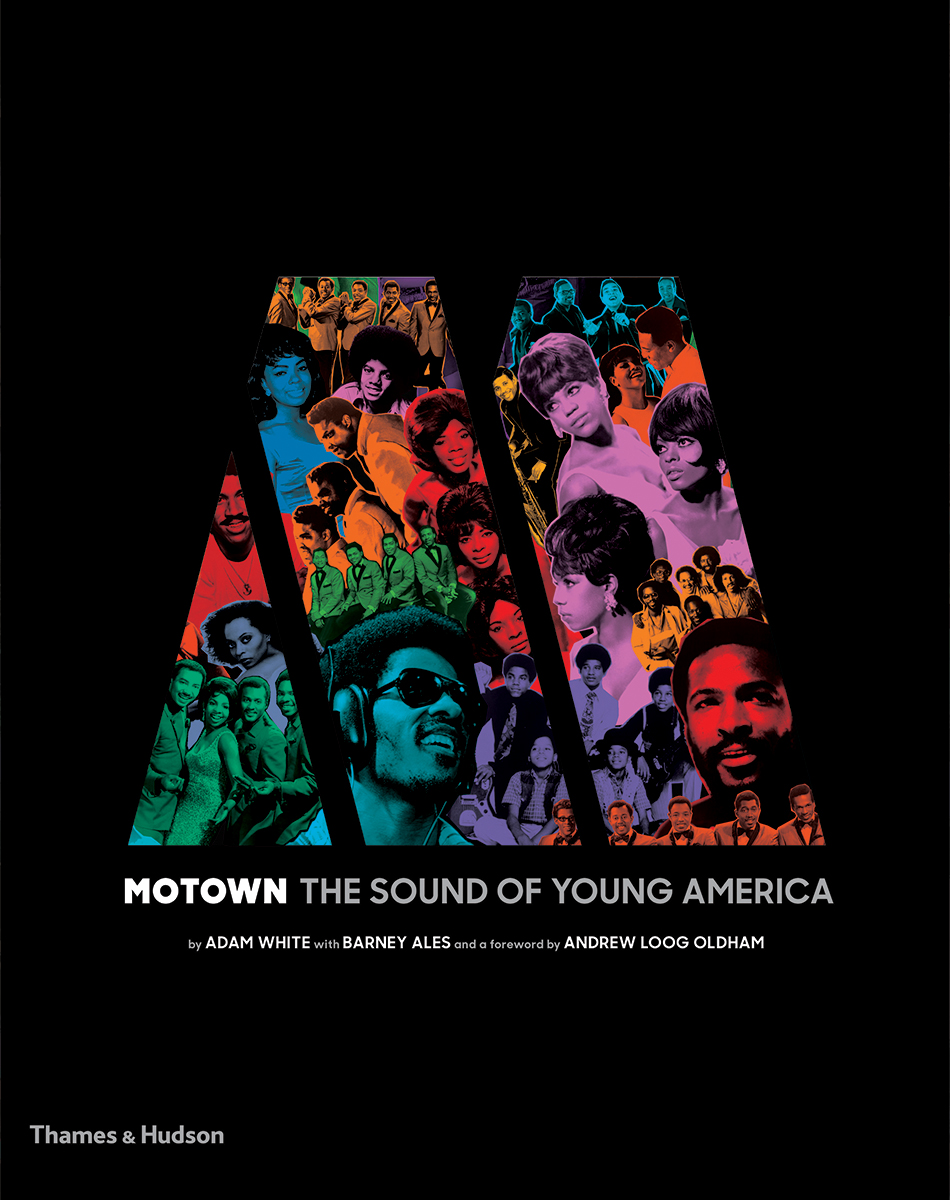

Hardback Publication of 'Motown The Sound of Young America'

With the 2016 hardback publication of Motown The Sound of Young America, (Thames & Hudson) by Adam White with Barney Ales, including a marvelous foreword by Andrew Loog Oldham, we finally now have the ultimate visual history of the pioneering record label.

In February 2019 a new paperback edition was published in the U.S. and U.K. by Thames & Hudson.

Most notably, guided by a very telling point of view that finally captures the record company’s fiscal reality along with the strength of a dream legacy, now told and illustrated against a background of momentous social and cultural changes in America.

Motown: The Sound of Young America, is the definitive print collection and history of the Detroit-based independent record company that became a style unto itself, a prolific and hugely successful production line of suave, sassy, and sophisticated music through the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

Contained in the 400-page volume are extensive specially commissioned photography of treasures, over 1,000 of them in gorgeous color and black and white, gathered from the archives, this deep-dive exploration also displays the graphic and design iconography that underpinned Motown’s extraordinary creativity.

The Supremes at the Hollywood Bowl. - Courtesy photo

It is one compelling and enjoyable read, parading the vision, hustle, muscle and sonic achievements of Berry Gordy, Jr. on behalf of Stevie Wonder, Smokey Robinson & the Miracles, Diana Ross & the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, Tammi Terrell, Brenda Holloway, the Jackson 5, the Temptations, Valerie Simpson, Nick Ashford, Kim Weston, the Holland-Dozier-Holland songwriting/producer team, arrangers Mickey Stevenson and Hal Davis along with numerous Motown veterans are also examined.

After the international success of "Shout," the Isley Brothers inked to Motown, scored a few R&B hits and a 1966 Top Twelve Billboard position with "This Old Heart of Mine," written by Holland-Dozier-Holland and Sylvia Moy. It was also recorded by Tammi Terrell.

In the Oct. 11, 1975 issue of Melody Maker, I interviewed Ernie and O’Kelly Isley of the Isley Brothers. We talked about R&B life and strife of the early sixties and their tenure at Motown.

“My older brothers can tell you a lot of stories about the way it used to be,” ventured guitarist Ernie Isley. “Things are different now for the black musician. Some people have been knockin’ at the door even longer. You can’t keep good music down. Eventually it will get heard.”

“Motown was like a school for us,” declared singer O’Kelly Isley. “Those guys knew everything there is to know about the business. We learned about production and songwriting.”

Motown: The Sound of Young America is packed with fresh insights gleaned from scores of interviews with key players, this terrific and awe-inspiring book delves into the workings and machinations of the Motown machine and details how a dedicated team of backroom believers, white and black, turned a small family business into a popular music powerhouse as America underwent momentous social and cultural changes.

Adam Whitehas written about music and the industry for more than forty years. He was editor-in-chief of Billboard, co-authored The Billboard Book of No. 1 R&B Hits and was Grammy-nominated for The Motown Story (1983) and Heaven Must Have Sent You: The Holland/Dozier/Holland Story (2005). White was vice-president of communications at Universal Music Group International from 2002 to 2012.

“Barney Ales and his crew – Phil Jones, Irv Biegel, Gordon Prince, Al Klein, Mel DaKroob, Miller London and more – got the records played and the company paid,” emailed Adam White to me in 2016. “We know the music matters most of all, but without that team’s nitty-gritty of promotion, sales and distribution, Motown might never have soared.”

Barney Ales was Berry Gordy’s indispensable right-hand man and Motown’s ultimate insider, whose job was to get the records played and the company paid. He rose to become executive VP and general manager, but stayed in Detroit in 1972 when Gordy moved Motown to Calif. Ales became its president in Los Angeles during his return to the firm from 1975 to 1978.

Andrew Loog Oldham discovered, managed and produced the Rolling Stones from 1963 to 1967. He worked as a producer for Motown’s Rare Earth label during the very early 1970s and produced the Connecticut group Repairs and Detroit band the Sunday Funnies.

“Barney Ales - the jewel in the crown,” described Andrew to me over dinner in 2016. “His efforts on behalf of Mr. Gordy and the artists were the primary reason the sound of young America graduated all over the world.”

Andrew and his lads covered Motown/Jobete Music assets "Money (That’s What I Want)," "Can I Get a Witness," "Hitch Hike" and "My Girl."

“'Can I Get a Witness' is a great young version by the Stones,” Andrew stated to me in a 2004 email interview.

“Mick (Jagger) was out of breath on this one as he’d run across Soho to UK’s Motown publisher’s Freddy Bienstock to get the lyrics. 'Hitch Hike' is a bit mindless and even though the track of 'My Girl' is a bit naff Mick nailed the vocal.

“But it’s the spirit that counts and Motown made you feel everything was possible. Its rhythms were often unusual for Top 20 fare and the lyrics and delivery spoke to young moments.”

***

During 2016, Andrew sent me his foreword to Motown The Sound of Young America.

In an email he wrote,” Long before a cartoon tongue came to be known worldwide as the essence of excess, Tamla Motown, as the label was called in the U.K., was a Brand, a 360-degree, vertically integrated, celebration of sound, style, and success. The Motown imprimatur on an unknown artist or an unheard new record was a guarantee of quality no other record company could equal. For us beat boomers, The Sound of Young America was as inspiring as the March on Washington was for Motown’s native speakers.

“Meanwhile, in a slightly shabby office located upstairs at Hitsville U.S.A. in Detroit, a young white man directed the distribution and monetization of Motown’s vast recording and publishing catalog. Berry Gordy, Jr may have been the Diaghilev to multiple African-American Nijinskys, but it was Barney Ales who dealt with the white rack jobbers and one-stop operators who were perhaps only a half-step removed from the jukebox racketeers.

“Ales had the vision to take the business international at a time when the likes of Epstein and myself were fumbling our way in the New World. Berry realized he’d found a partner who could help make the white-dominated music industry dance to his tune. Ales remained vice president of sales at Motown until 1972 and, after a time running his own Prodigal Records, returned in 1975 to become president.

“There is no one more qualified than Adam White to take you behind the scenes, into the halls of Hitsville and onto the factory floor where Berry Gordy and Barney Ales staged a revolution. I feel blessed to have known music man Barney Ales. Now it’s your turn.”

Musical history now illustrates how vital television exposure was for Motown and the label’s recording artists. None were more essential as a booking on The Ed Sullivan Show.

“The relationship between Berry Gordy’s Motown label and The Ed Sullivan Show made music and television history,” stressed filmmaker Andrew Solt of SOFA Entertainment, owners of The Ed Sullivan Show library.

“Soon after the Supremes’ debut on Sullivan (December 1964), it was clear that showcasing the latest Motown releases on CBS on Sunday nights (35 million viewers was average) until 1971 was a way to expose the record company’s newest hits and boost the show’s ratings. Sullivan introduced nearly all the Motown acts, including the Supremes, the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, the Four Tops, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Marvin Gaye, Gladys Knight and the Pips, and the Jackson 5.”

“It was really a battle in those days to get black artists on network television in prime time,” emphasized Barney Ales.

“Sammy Davis Jr. and Nat Cole were about the only ones—anyone else, they just weren’t accepted. But when the Supremes broke through, we knew we had an opportunity. They looked so great, as well as sounding great. And Harvey Fuqua and Maxine Powell did a wonderful job, grooming the girls, getting them ready for prime time.

“The Ed Sullivan Show was the real breakthrough. Sunday nights, millions of people watching. Once Sullivan took to the Supremes, we knew we were on the right track. And album sales picked up like crazy whenever they were on, so we always made sure to tell the distributors they needed to check their inventory. After the Supremes, we got everyone on Sullivan’s show: Stevie, Gladys, the Temptations. We had a good relationship with the producer, Bob Precht. He liked Motown, and Esther, Berry’s sister, used to take the dressing room keys afterwards as souvenirs. They’re probably somewhere in the Motown Museum to this day.”

“For us, being on The Ed Sullivan Show was so much more than record sales,” underscored Mary Wilson of the Supremes during 2003 and 2016 interviews.

“It wasn’t about promoting us. It was about that we had grown up watching The Ed Sullivan Show. We had grown up watching shows where you didn’t see a lot of black people starring on those shows. For us, we were like every other family in America who spent hours watching Ed Sullivan. So for us, being on the show was such a great honor. Because we were there to see the world changing. To see America changing. We were excited! We’re on The Ed Sullivan Show.

“We came from a time when a whole family of all different colors didn’t sit around ‘watching black people on television.’ The Dick Clark tours where before us there were segregated hotels.

“For us, that is what it was all about. We were part of that change. We were part of helping America to see black people, black women, being proud, beautiful and successful. It wasn’t just us, many people before us. But they didn’t have the television to expose them to that wide range of people as we did at the time when we came. We were lucky. And we stood on a lot of shoulders. But we were there when the doors opened.

“The other thing was that we were seen in color after our initial appearances were in black and white. Recently, my granddaughter was watching a DVD collection of the Supremes. And she said to me. ‘Grandma! What happened to the color?’ ‘Cause she has never seen a black and white TV!

“Our songs from 1964, ’65 and ’66 were heard in 1967. Berry Gordy and the A&R department knew what was happening,” reinforced Ms. Wilson.

“And we didn’t have to think about that. But we were happy for it. And as a group, it took us into areas we wanted to go, which is great. I loved to tour. I went to the Whisky a Go Go in the sixties. I always went out to see everybody, loved seeing other acts.

“I’ve toured with Bill Wyman in England. And he and I always talk about The TAMI Show. We all thought James Brown was gonna close the show. And all of a sudden we heard this rumor back stage that the Rolling Stones were closing. Bill said they were all scared. And they became great friends, which was really cool.

“I’m just so fortunate to have known so many brilliant people. However, just to talk about Holland-Dozier-Holland was such a wonderful experience for our growth and journey. They took us through the times that were going on in the world. Each time they would bring us to another level. The records show this. We did 'You Can’t Hurry Love' and 'You Keep Me Hanging On.' That’s why we had wanted them in the beginning. We had to grow into that. After we no longer had H-D-H there was a period where we didn’t have anyone. That to me was the worst period musically.

“So we got with Frank Wilson who was just brilliant,” enthused Wilson. “What was great about him is that now it was more a West Coast. It wasn’t Detroit. We did everything pretty much on the West Coast, even though we still recorded in Detroit.

“Frank brought a different feel. There’s a wah-wah pedal on 'Up The Ladder To The Roof.' A more seventies soulful kind of feel. And after we no longer had Diane. Berry Gordy was very helpful in bringing Jean Terrell, who I just adored. And she was the best replacement for Diane, not that anyone could ever replace Diane.

“For me, the only group was the three of us. Me, Flo and Diane. The seventies was a seventies group. And Frank was able to capture who we were at that point with Jean Terrell. He was just a brilliant producer.

“We had a whole other concept when we moved out to the West Coast. We did our sessions in Los Angeles. Hollywood. The Motown studio,” Mary remembered.

“In the earlier days we actually recorded with the musicians, do the vocals a couple of times. For years we recorded right there with the musicians. The magic for me was lost after we became really famous because then the tracks were laid down and we would come in and do it without seeing the musicians. The magic was when we recorded with the musicians. That was the beauty.

“Now, everyone is asking me about the musicians” Wilson volunteered.

“From my perspective we always knew and felt that. The public now can appreciate them as individuals. We always appreciated them that way. We as artists had to look out for ourselves, and we had our PR pushing us. The musicians didn’t have PR companies pushing them then. See the difference? Thank God now they can get their final due which they totally deserve.

“I want to be really clear about this: No one really intentionally didn’t talk about the guys. It wasn’t that, it’s just the way the business was. The artists out front,” she underlined.

The core foundation Motown session musicians aka the Funk Brothers, the relatively anonymous studio cats on the instrumental tracks, were: Joe Hunter, Johnny Griffith, and Earl Van Dyke on keyboards, Robert White, Joe Messina, and Eddie Willis on guitar, James Jamerson and Bob Babbitt on bass, Jack Ashford on percussion and vibraphone, Eddie “Bongo” Brown on congas and Benny Benjamin, Richard “Pistol” Allen, and Uriel Jones on drums.

Paul Riser, a Motown trombonist/arranger/producer, who has worked with Lauryn Hill, Quincy Jones, Aretha Franklin and Stevie Wonder complimented them. As individuals they were great musicians, as a unit they were the best.” Riser co-wrote Jimmy Ruffin’s poignant recording "What Becomes of the Brokenhearted."

***

During a press junket for 2002’s Paul Justman-directed documentary, Standing in the Shadows of Motown, that chronicled the Funk Brothers, I talked to drummer Uriel Jones.

His hard-hitting back beat enhanced the Temptations’ "Ain’t Too Proud to Beg" and "Cloud Nine," "Ain’t That Peculiar" from Marvin Gaye, and both versions of "Ain’t No Mountain High Enough," courtesy of Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell and Diana Ross.

“If you’re playin’ with a bass player and he’s all over his bass all through the tune you can’t grab no pocket,” stated Jones. “Whatever [bassist] James Jamerson played with his fingers I could play with my foot the same syncopation. That’s why we locked in so good on all those tunes.

“What I learned from [drummers] Benny Benjamin and [Richard] ‘Pistol’ Allen was self-discipline. You’ve got to have that, you know, to get into the pocket. Because if you’re playin’ too much you can’t get no pocket.”

I mentioned to Uriel that on Motown records the drummer wasn’t buried in the mix. “No they weren’t,” agreed Jones. “Sometimes they let us start the tunes off. You know one reason why we weren’t mixed down low because we were the elders, and most of us were grown musicians and most of the producers and writers would always look up to us. They were younger. See, they would come into the studio sometimes with a lead sheet and the Funk Brothers would be the arranger

“We recorded in a small studio as you know. There was never a bandleader in the studio. If it was larger we wouldn’t have got the sound we got. And in the small room everybody had eye contact with one another. And we would say we wish we could sit up on stage like that,” exclaimed Jones.

“Norman Whitfield at the time was a number one producer, so at that time he could afford to branch out into new stuff, where other producers couldn’t afford to take a chance. When we started with Motown, they didn’t begin with the psychedelics, and we gradually got into it. We really primed ourselves so when it did get into the psychedelic pocket and it was about the same from going from jazz to rhythm and blues. Like on 'Can’t Get Next To You.'

“Norman would do the tracks and then dub in the singers and he would call us back sometimes to overdub.

“And if there was an advantage about us cutting without the singers, it was that they then had a choice of who would sing that song. They’d try an artist. If it didn’t work, they’d try another. They were looking for the right combination. The one who got the record was the one who could fit the format.

“Like I’ve said before, we put the tracks down and built the basement on the first floor. And what you do with the rest of your house is up to you. What you put on the top and the bottom.

“Jack Ashford is on a lot of those tunes and would be playing beats usually done on your hi-hat or something. Jack had that goin’ always through the tune. That way if you wanted to veer off for a couple licks to do something you never did lose that groove. Jack and I would feed off one another. He is a clock man.

“A lot of times if you ain’t right in the groove for one day or somethin’ I look at Jack and listen to Jack. I may be pullin’ down or pullin’ up and I’d catch Jack’s eye and I could tell by the way he looked he was trying to keep me in the pocket. And we never played any differently if the track was going to be for a male or female group ‘cause we were on a job.”

I had an audience with percussionist and vibraphonist Jack Ashford, who first came to Motown at the request of Marvin Gaye in 1963. Ashford is the author of Motown: The View From the Bottom.

Jack’s tambourine is evident on Edwin Starr’s War, Marvin Gaye’s "What’s Goin’ On," the Miracles’ "Ooh Baby Baby" and "Where Did Our Love" Go by the Supremes.

“With the tambourine on the sessions, I didn’t know the lyrics, or the melody. There was none. So like with Norman Whitfield, he was a frustrated tambourine player, anyhow. He gave me a little more leverage to be more creative spontaneously. Maybe a little more than some of the other producers because he depended on a lot of rhythm, as you can tell from his music. I had complete freedom to do what I wanted to do. But I played off my comrades and listened to what they did and the reason I did some of the things on "War," was because of something that was happening in the rhythm section. I had no idea it would have such an impact,” Jack confessed.

“My process…Well, number one and this is the one that I’ve used ever since I first started doing these things. OK. I personally don’t think about what I’m getting ready to play. I really don’t. On sessions the first thing I would listen to is what Jamerson was doing and what the drummers were doing. Because it was important that I locked into them and what Eddie ‘Bongo’ Brown was doing on congas or bongos. It was important not to get in the way because I could do what I wanted to do. There’s plenty of room to move around rhythmically with a tambourine.

“The whole thing with a tambourine period is to control the cymbals. This is the sticking point for everybody because when they slap it the cymbals are going for themselves. And if you don’t control them then you’re in the way!

“So my approach is to control the cymbals and make them do what I want them to do. Because they’re gonna get heard and if you make them do what you want them to do now you’re adding and enhancing what’s being laid down by everyone else.”

Joe Messina was the guitarist on "I Can’t Help Myself," "Your Precious Love" and "Dancing in the Street."

A jazz musician in his teens and by his mid-20s he was playing on the nationally televised The Soupy Sales Show, alongside such guests as Miles Davis and Charlie Parker. Messina was with the Motown label until operations were moved to Los Angeles in 1972.

Did Joe know he was playing on a hit when he cut “Dancing in the Street?”

“No, never expected it. That’s one of the nice things. The beat was a little different and everybody automatically started to dance to it.

“Paul Riser was my favorite arranger at the label. His arrangements were very interesting, and at the end, our charts were like little scores. Paul was very detail-oriented. He could write whatever he said, whereas in the earlier days they would hum the stuff to you and you would have to remember what was hummed to you.

“My favorite vocalist was Marvin Gaye. We never associated. We did our tracks and then he’d overdub. Marvin was a drummer and it made it a little bit different. Levi Stubbs of the Four Tops was my guy as well.”

“It's really important to bear in mind that the Funk Brothers were primarily jazz musicians reinterpreting R&B...that makes them way different from the Hodges Brothers or Booker T. Jones and Cropper or the guys in Muscle Shoals,” emailed multi-instrumentalist and record producer Don Was, a Detroit native.

“They were sophisticated cats who brought a deep understanding of harmony and lyricism to these pop songs...They were used to wailing on, say, Duke Ellington's songbook - which was way more complex than the early Motown music. One of the beautiful things about The Funks is that they never condescended to the audience or the material.....they used their musical knowledge to mine the emotional gold buried in the songwriting and lifted up every track that they played on.

“Remember, also that these guys were local Detroit jazz musicians - the basic geography of the situation meant that they were a little bit cut- off from the mainstream cultural centers of New York and L.A....the insular, provincial nature of the scene resulted in a quirky reinterpretation / misinterpretation of then-current national R&B trends...oftentimes, reinvention outshines the original source from which it draws inspiration.

“A good case in point is the otherworldly bass playing of James Jamerson. If Berry Gordy had simply imported guys like Richard Davis or Milt Hinton or whomever was in fashion for New York sessions, these records might have ended up sounding like everything else out there at the time.

“Instead he entrusted the sessions to an unknown bass player who had invented a whole new way to approach the instrument. Somehow, Jamerson somehow managed to play these melodic figures on the upbeats while still implying a relentless downbeat-based groove....he was like a guitar player, Latin percussionist, funky bass drum and bass player all rolled-up in one! He's such a charismatic musician! In fact, every one of the Funk brothers had really strong, unique musical identities. You couldn't have made those records with different cats...and God knows that everybody tried!

“In the seventies I was in a band with Richard ‘Pistol’ Allen....he wasn't a big guy....played really light....but he could swing like crazy and he had an enormous musical personality that belied his small physical stature...you could tell that he was the guy who drummed on those records even when you were playing songs that had nothing to do with Motown!

“One cat who I think has not been given his due as a Funk Brother is Dennis Coffey.....maybe that's because he came along later like Bob Babbitt. His first session was 'Cloud Nine' - Dennis introduced the wah-wah pedal into the Motown vocabulary.

“I used to go hear him play in a trio with a wonderful organist named Lyman Woodard....he could play all the Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell stuff but he'd add all these funky rhythmic figures....it was a previously unheard style of guitar playing - very original. He still gigs in Detroit.....you could take me into a club blindfolded and, even today, I could identify him as the guitar player in ten seconds. Gordy and his minions had a keen talent for potting these characters and weaving them into the Motown fabric.”

“I’m on a lot of the Jackson 5 records cut in Hollywood: 'I Want You Back,' 'ABC,' 'The Love You Save,' specified guitarist Don Peake in a 2014 interview. “I was in a core session group that, in a sense, replaced the Funk Brothers, who did the Motown sessions in Detroit. We didn’t want to replace them, but Berry Gordy moved out here.

“Benjamin Barrett was a very powerful contractor. He worked with Gene Page a lot, and that’s how he knew me, ’cause Gene always used me on Phil Spector dates. Benjamin called me on the telephone. ‘Hey Don, Motown is moving to Los Angeles. I’m forming a staff band and want you to be one of the guitarists in the orchestra.’

“I went into the room, and there was David T. Walker playing guitar, Louie Shelton on guitar, and drummer Gene Pellow. Some of the records have Paul Humphrey. He wasn’t like Hal Blaine or Earl Palmer. He was very understated. He was chill. The pianist was Joe Sample, and the bass player was Wilton Felder, sax player for the Crusaders, but he played the bass for Motown.

“Ben Barrett told me to go over to the mom-and-pop studio on Ventura and Colfax—Freddie Perren’s studio. These were different sessions than with Spector and Brian Wilson. Freddie had us in a compact core group. It wasn’t the five guitars, two pianos, two drummers, two bassists. This was more like Detroit combos, where the bass was featured. It was a whole different kind of music.

“Playing with the Jackson 5 was just exciting. I had played with the Everly Brothers from 1962 to 1964, so I was into the harmony thing.”

“I have picked up as many hints on guitar playing as I can from Don Peake, who is the Everly Brothers guitarist,” Keith Richards once proudly proclaimed in a 1963 issue of New Musical Express. “He really is a fantastic guitarist, and the great thing about him is that he is always ready to show me a few tricks.”

“I made all those Monkees records, like Mary, Mary. I did the chart. I played on some, and arranged some. So, I was on Monkees, Jackson 5, and then the Partridge Family,” summarized Peake.

“The kids were all there. I watched them do their vocals. Michael was magic. All of us looked at Michael and said, ‘Oh my God. This guy is amazing.’ We knew, like with 'ABC,' we were making a great record. Sometimes you can just tell.

“When I played on the Righteous Brothers’ 'You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin,’ everybody in the room knew it was going to be monster. I played on so many songs by the Jackson 5, including a wonderful record, 'Maybe Tomorrow,' which has an electric sitar. That’s me on the Danelectro.

“We started recording down on Romaine Street, just south of Santa Monica Boulevard, near La Brea. The Motown studio, the Sunset Room. We also worked at the Crystal studio. It was a big room. The Motown studio was a little smaller. We did some Supremes records there with producer Frank Wilson.

“Then Marvin Gaye walked in. On his session for 'Let’s Get It On,' it was me and Arthur Wright on guitars. I do the lead intro lick. I hit an open G string and I made a mistake and you can hear it on the record.

“Freddie Perrin was very methodical. He was much more specific, like with arranger Jack Nitzsche on 'River Deep,' 'Mountain High' and 'I Got You Babe' with arranger Harold Battiste. They were written out but with Freddie, he was a wonderful string arranger and a genius.”

***

During a 2003 interview I wondered if Mary Wilson had any observations or theories about the durability of the Motown catalog and performers.

“I think all of the things we are recognizing now, the Motown label, the Funk Brothers, musicians, Berry Gordy, here we are 40, 45 years later and people are still re-recording those songs. Berry Gordy was an innovator, and he knew talent when he saw it. He only accepted the best.

“He allowed people to create on their own. He allowed the producers to really inspire each other. There’s no real answer to your question other than I know when I was recording those songs, it was the people. It was the music…Who knows. Any bass player out there listened to Motown records to learn how James Jamerson played.

“Any new female group coming up will definitely try and take something from The Supremes. It was like we were the model for music. The Motown sound was the model. And the music is universal.”

Ms. Wilson has seen the inclusion of her Supremes’ songs and many Motown master recordings utilized in TV and film soundtracks. What did she think about hearing the original studio sessions and cover versions on the airwaves?

“Then, we didn’t think in those times the songs would be in TV or film. Like on 'China Beach' they use 'Reflections.' Later, seeing that these songs were such great hits, and the years showed that they were really fantastic, other people recording them, you began to realize that what you know all along everybody else knew as well. We knew it at the beginning that they were great recording then. But when everyone else got it, what we knew was true. That’s the great part about it.

“When a Motown song is played on the radio, or a tune on TV, in a film…I always get that…When I hear them…For us, we were a family, so for us, the loss is greater than it is for you guys, for the fans…Because it’s like losing our brothers and sisters. There’s a huge sadness.

“Their contribution continues…I saw Eddie Kendricks’ face flash across the screen recently when I was watching TV, which I don’t do too often, and I almost cried. I felt the tears well up in my eyes. It’s always there. Every one of us at Motown feels the same way,” she sighed.

Berry Gordy Jr. was born Nov. 28, 1929, in Detroit, Michigan. A former boxer and assembly line worker, and veteran of the Korean War, Gordy, in 1955, ran a jazz record store, his first foray into the music business. Although the shop failed, he didn’t give up. He wrote songs, and got his first break when Jackie Wilson cut some of his compositions, including 'Reet Petite,' 'That’s Why (I Love You So)' and 'Lonely Teardrops.'

Gordy’s sisters Anna and Gwen, along with Billy Davis, started the Anna label, which scored a major success with Barrett Strong’s "Money (That’s What I Want)" in early 1959. Gordy, who was involved with the Anna label, then launched the Tamla label. Motown itself, with Berry Gordy at the helm, soon followed.

The Motown Records label in Detroit, Michigan was founded on January 21, 1959 and incorporated as Motown Recording Corporation on April 14, 1960 by Berry Gordy, Jr., who merged his two associated imprints, Tamla (whose initial release was Marv Johnson's "Come to Me" on January 21, 1959) and Motown (debut pressing was the Miracles' "Bad Girl”).

At the end of the 1968, and by 1972, having outgrown its Hitsville USA origins in Detroit, Gordy moved the Motown operation, now a true entertainment complex and the largest black-owned corporation in the country, to Southern Calif.

Gordy eventually withdrew from the day-to-day operations, and finally, in 1988, he sold his brainchild to a major corporation, MCA.

***

More recently Motown shifted ownership to the PolyGram group of companies, now called Universal Music.

He’s still involved with Jobete Music, the publishing company that houses the widely utilized and still influential copyrights.

Berry Gordy is very active in the production of a 2019 documentary Hitsville: The Making of Motown, which will utilize his personal archive and behind-the-scenes footage from the Motown vaults.

In 1994, Warner Books published Gordy’s autobiography, To Be Loved. The book’s title is taken from a song Gordy penned for “Mr. Excitement,” Jackie Wilson.

During 1994, I interviewed Gordy inside his Bel-Air, California mansion. Our meeting was arranged by Ewart Abner, a former president of the Vee-Jay and Motown labels. I chatted with Ewart about two of my favorite singers: Dee Clark and Nolan Strong of the Diablos.

I had first met Abner in 1974 at a Stevie Wonder show in San Diego where I and a gal pal sang warm-ups with Stevie’s band at a backstage rehearsal at the San Diego Sports Arena. Stevie’s percussionist at the time, Ollie E. Brown, was a neighbor of mine in West Hollywood.

***

Portions of my Berry Gordy interview were published during 1994 in HITS, BAM, MOJOplus rocksbackpages.com this decade and displayed in my 2017 book Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and Interviews Collection Vol. 1.

Ewart Abner instructed me to set up my tape recorder. We were also being videotaped for Gordy’s own archives.

Q: Why did you write To Be Loved?

A: Several reasons. The history, the legacy. As a general thing I wrote it to, of course, set the record straight, which had long been misunderstood. I wrote it because there were many unsung heroes in my company that were part of this operation, you know, who were not known and who taught the artists how to walk, sing, dance, talk and even eat, and stuff like that. And they’ve been with me 25, 30 years, these people. The chaperones that went on the road so much of their time and their life, really being very strict on these artists, and working with these artists.

And then, I wanted to tell my own story in my own words. Because so often, I have wanted to read about my heroes: Dr. King, Jackie Robinson, JFK, Sugar Ray Robinson, Joe Louis. I would have loved to have read their story in their own words. Because when others write about you, the write about what you did or what they think you did, and how they think you did it. And it’s nothing like writing your own story about not only what you did but how you felt doing it and, more importantly, why you did what you did at that particular time. And that’s what I tried to do.

Then, in setting the record straight I wanted to set the young minds at ease, put the young minds at ease. Not only the young minds but the old minds, the people who have been following me for 35 years, who believed in me and Motown no matter what they had heard or read in the papers. I felt I owed it to them to do that.

And, whether I like it or not, I’m a role model, you know? So I wanted young people to know that a company like Motown could never have been built as beautiful, and as big and as strong as it has become, and the music created like it was, through devious means. Being in the Mafia, cheating artists and all that garbage, you know? And, that’s why I wrote it.

Q: I now that a lot of people reading this interview might not be aware that you had a life from age 18-29 before Motown began. You talk about it in To Be Loved: Working at an automobile plant and the 3D Record Mart. Writing songs. A ten year period where being in the real world probably paid advantages later.

A: The real world. I learned a lot. If I hadn’t worked in the factory at Lincoln-Mercury I wouldn’t have had the assembly line idea. I wouldn’t have written a lot of songs. I wouldn’t have been locked into a place where I had to write a lot of thoughts I had. I saw what the real world was like and I saw what I wanted and what I didn’t want.

Q: I wanted to discuss Jackie Wilson. People are rediscovering Jackie partially due to some of the repackages.

A:The most natural artist I’ve ever seen in terms of dancing, vocals. His voice was the strongest. He could do opera, he could do rock, he could do blues and he created the most creative singer that I’d known.

“As I said in the book, he never sang a bad note. Maybe a bad song, but never a bad note…One of the most talented artists I’ve ever seen. ‘Cause I’m talking about all great people here. So when I say talented in another way, I mean he was the most natural.

Q: Was he more dynamic live than on record?

A: Yes, of course! He was more dynamic live than on record. And he could dance, and could do flips and splits. Different than Michael.

Michael studied a lot of people who did a lot of things. Jackie did not study anybody but Jackie. Jackie was Jackie, the most natural, innate performer, probably, that I’ve ever seen. He had nobody to study that I know of. Jackie was an original, probably the most original artist that I’ve ever seen.

And he should be rediscovered. Because he created stuff and he could wink on cue. I said it in the book. He could do things, do a spin, and then wink at the girls.

Q: What was your first impression of Smokey Robinson?

A: Well, Smokey Robinson, my first impression was he was great, a great poet, but he didn’t know how to really write songs, or put songs together. When he learned how to put stuff together and he really understood, Smokey was incredible. When I turned down his first 100 songs, he got more excited with every song. I said, “This guy has to be either crazy or one of the most special people I’ll ever meet.” He was incredible. He turned out to be one of the most special people I ever met.

Q: And with an angelic voice

A: Oh, yes. Pure. And then, he got it and understood it. So now Smokey has succeeded at the cycle of success. It takes a lot of character, because you are tempted along the way. The cycle of success is a vicious cycle. It takes you into places. People offer you things never offered before. To succeed and be successful is tough so it takes a lot of character. You got to keep your same values. So Smokey has done that. The Four Tops have done that. And most of the Motown artists have it drilled into them and they were all very tight.

Q: The Four Tops?

A: The epitome of loyalty, integrity, class. They’ve been together for 40 years, the same four members. That is unheard of, impossible, and I just admire them so much. I admire them the most of any of the artists.

Q: The Temptations?

A: Legends. They’ve managed to keep their look and their style all these years and they’ve changed members constantly, but Otis and Melvin have done just an amazing job of finding one major talent after another. Because they are legends, people want to be with the Temptations, and they have proven that the group is stronger than any of its parts. I don’t care how great that part was, the Temptations are an institution.

Q: Diana Ross?

A: Diana…Special, magic, sensitive. When she does a song like “Somewhere” in front of an audience she still cries, I mean, I’ve never seen her do "Somewhere" without crying. In fact, we used to stop her from doing it every night in the week. The Bernstein song from West Side Story. She was so dramatic and then she did the second ending and it was too much emotionally. She’s so emotional and she gives all to her audience and she is sincere about it and serious about it.

Q: Marvin Gaye?

A: The truest artist I’ve ever known. Whatever he was going through in his life he put on records. So if you want to know Marvin just listen to one of his records.

Q: Stevie Wonder?

A: Innovative. The most innovative person that I’ve ever known. But also unique with his tones and his voice quality and all that. He was as close to genius, and I don’t like to use the word genius, you know. Marvin could have been a genius. I don’t like to throw it around, but Stevie is one of those kind of special, special, special people that had a sound, and he’s quick. He’s creative and he can make up something very quick.

Q: And he is involved in technological developments.

A: That’s what I’m saying. Contraptions. He would take technology. He was the first in technology. He’s an innovator.

Q: Michael Jackson?

A: Greatest entertainer in the world and one of the smartest people and businessmen in the world. He conducted his own career, basically. He knew what he wanted. And from nine years old he was a thinker. And I called him “Little Spongy,” because he was like a sponge and he learned from everybody.

He not only studied me, but he studied James Brown, Jackie Wilson, Marcel Marceau, Fred Astaire…Walt Disney. And he bought the Beatles’ catalog. Michael is nobody’s fool. Very bright. Very smart.

Q: The Holland, Dozier and Holland production and songwriting team?

A: H-D-H was phenomenal. They came up with hit after hit. They started a thing. They had a lock on the Supremes and they took them, and did stuff on Marvin. H-D-H was absolutely brilliant. The three of them were different and they all complemented each other.

Eddie (Holland) did mostly vocals, Brian (Holland), I thought was the most talented, creative person. He was my protégé for many years. I thought Lamont (Dozier) was also a good writer, and he was good on backgrounds and this and that and so forth. But Brian would do something like he would play and sing and create something and all he would give ‘em was, like, “sugar pie honey bunch,” and pass it on. So they had their own assembly line. And they were tremendous.

Q: The terrific producer and versatile songwriter Norman Whitfield?

A: Norman to me was probably the most underrated of all the producers, because he was producing by himself. And he would deal with different sounds, different beats, change with the times and write his stuff, and also Barrett Strong would work with him as a writer on many of his things. Norman was innovative and he had fire. And he had a different kind of style.

His beat was different and could go from "Cloud Nine," "Psychedelic Shack," "Papa Was a Rolling Stone," to "Just My Imagination." He was sensitive and I think he could do so many different types of things. Then he’d come right back with “War” and then “Ain’t to Proud to Beg.”

He could take one chord, like on "Papa Was a Rolling Stone," and play the same chord and do all these different beautiful melodies and things that many people could not really imagine this guy doin’. And I would watch him and he did it all by himself as a producer. He would work with five guys in the Temps and he would change leads on each one. He would pick the right lead for the right song, ya know, and he’d utilize all five of those leads in a song that was just incredible.

When I listen to ‘em today, now that I have time to listen to ‘em, I’m saying, “Wow! This guy was probably the most underrated producer we had.

Q: Motown began with 45RPM singles. Then the album format, eventually 8-track tapes, cassettes and now compact discs. Were you personally impacted by the growth of the LP market?

A: Now very much. We were about producing songs that were great. And so a lot of the producers who would be coming to our Friday morning meetings, they would say when the song wasn’t that great. “Oh, that’s an album tune. That’s just going on the album.”

I’d say, “No. No. There are no album tunes. Every tune has to stand on its own.” We didn’t look at album tunes as such. We would pick tunes that were hits and that’s why they would go on albums and pull out a hit here, a hit there, you know? So it didn’t impact us that there were albums and we had departments and all that stuff. But as far as recording, unless there was a concept album and things like that, we would say there are no album tunes. We’d say that all the time.

‘Cause there’s great songs that were great but they were produced wrong, or maybe the wrong singer, or maybe this or maybe that. But the quality is still there. So let’s look at all that. I started as a songwriter. I love songs, so you know, that’s a hobby.

Q: What about compact discs?

A: They were cleaner. When we were first told about them we couldn’t get them. I mean, no one was manufacturing them, you’d have to wait, and it was a problem. And the cost was just incredible and you had to order so many before you even got them. We were just a small company and the CD manufacturers, and all these new things, were things that confused us more than anything else. Because we were about hit records and one record at a time and different producers were doing different things, so I don’t know a lot about how they affected me emotionally or stuff like that.

Actually, we made money on every new format that came out because it was a new configuration. So they’d buy all over again, whatever it was. Then you have software, that’s what it is now.

That’s why Jobete is so important to us, because of the songs and its software. Whatever it is, a great song is a great song. That’s all it is. And whatever configuration comes, we don’t worry about the configuration. We worry about if we have the product. And that’s what we’re doing going into Jobete saying, “Hey, before we do anything else, let’s make sure we have great songs. Make sure these songs are still great. Let’s look at all the other 95% of our songs.”

Q: I was always impressed that you later had a spoken word label at Motown, the Black Forum, where the voices of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Stokely Carmichael, Elaine Brown and Imamu Amiri Baraka, among others, were recorded.

A: I put out several things by Dr. King, including The Great March To Freedom in Washington, probably the biggest, I Have A Dream. One of the things in those days, in the ‘60’s, there was a civil unrest and the various people who had things to say.

***

I was very closely connected to Dr. King and liked his philosophy and he taught me the wisdom of non-violence. As I said in To Be Loved, I was never like a “turn the other cheek kind of guy,” you know? I wasn’t brought up that way. In the inner city you don’t do that.

But he taught me the wisdom of non-violence. While we were victims, others were victims, too. White people were victims when they let their prejudices hold them back. He was more with my philosophy of communicating with people around the world. Understanding. I think we all want the same kind of thing. We all want peace, we all want love. We all want togetherness. And I think one thing that music has done is brought people together with the same ideas. Forgetting what color of their skin is and all that.

Are you hip or square? There are black people that are not hip, and there are white people that are hip and it’s like, “Are you hip or are you square?” Are you this, or are you that? And then you forget about whether you are white or black, or this or that. And so, we had a family of people that were dealing with that fundamental thing about communicating love.

Life is not nearly as complicated as people make it. See, it’s basic. We got to get back to basic values and basic communication. Two and two is four. And all people want the same things, I constantly say. Each one of us is different though, and I tell artists to bring out their own uniqueness. That’s why you’ll get a Stevie Wonder, a Marvin Gaye, a Smokey Robinson. You’ve got to nurture that. That’s what we try to do. Nurture their difference.

“And so it wasn’t me that was the genius. If I was a genius of anything, it was bringing out the genius of others, because if they reach their potential then I had felt that maybe I could reach mine. So in bringing out the genius in others and finding it, sure, it was hard and tough, but your clues will tell you. And then, stopping them from focusing on other things other than what they’re doing.

And there are still 99% of the people, in my opinion, running around there now with this great talent, great art, great ideas like that, but they will never make it through.

“The idea is that when you make it through the fame, fortune and riches and power, and you are not the same person you are when you started out then you have been a failure. I don’t care how much money you got, fame or fortune you got. You got to be the same person that you started out with. And when you are then you can consider yourself a success.

HARVEY KUBERNIK is an award winning author of 15 books. His literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and Interviews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018.

Harvey’s The Doors: Summer's Gone has been nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections Awards for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research.

During November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz.

Harvey Kubernik’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown, that initially was published in 1995 in Goldmineand HITS magazines has been licensed for inclusion inThe Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett to be published in 2019 by Oxford University Press.

This century Harvey penned the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry,Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special andThe Ramones’ End of the Century.

In November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California).