The name of Todd Rundgren’s upcoming tour––whether it happens on schedule or not, given the current Coronavirus pandemic––fits him perfectly. The Individualist, A True Star Tour combines the title of his 1995 album (also the partial title of his 2018 autobiography), and his mythical 1973 album, which he is reviving again for the occasion.

The Philly soul boy started his career fronting America’s psychedelic garage rock answer to The Beatles and other British Invasion bands, The Who, The Yardbirds, and The Move. Their single “Open My Eyes” is considered Nuggets gold, but was the B-side of that single, “Hello It’s Me,” that became AM gold when re-recorded for his ambitious, double-album, Something/Anything? That landmark release, aside from providing power-pop disciples one of their sonic commandments in “Couldn’t I Just Tell You,” proved that he was capable of pulling a Beatles White Album, showcasing a perfect balance between Brill Building-caliber hits and Stockhausen/Zappa-esque sound-collage. It also delivered avant garde experiments that had him breaking the fourth wall like Bugs Bunny to the audience (going meta, if you will) with reflexive commentary on how he not only employs record making techniques (such as “punching in” and “white noise”) but describes them while challenging the listener to notice them as if they were Easter eggs in a video game.

Photo by Richard Kerris.

It was this command of songcraft and studio wizardry that would earn Rundgren the reputation as the highest-paid producer at one point, having helmed and/or contributed to albums by Grand Funk Railroad, New York Dolls, Badfinger, Meatloaf, Patti Smith, Daryl Hall & John Oates, Cheap Trick, The Psychedelic Furs, and we’ve hardly scratched the surface of his staggering and illustrious resume. But even while on the precipice of stardom, he went out of his way to sabotage it by choosing art over commerce. Shortly after refusing to release more singles and halting the hype machine behind Something/Anything?, Rundgren took listeners to Never Neverland with a magical, mysterious, mind-blowing, mescaline-fueled adventure into his vision of Utopia, the pseudo-concept album A Wizard, A True Star. Reaching for the stars instead of stardom, he quickly approached the outer limits of the recording medium, cramming songs and sound to the very edge of the vinyl LP. Eschewing singles, the record was largely dismissed, though they “got it” in England where the NME’s Nick Kent praised it.

To be fair, Stateside, Patti Smith wrote a prescient review for Creem musing that “Todd Rundgren is preparing us for a generation of frenzied children who will dream of animation.” The quote can give you the chills, when you think of how Rundgren would not only go on to pitch his graphics software to the founders of Pixar and ILM, but also how as the years passed a veritable cult of musicians from Prince to Trent Reznor to Tame Impala and others have incorporated A Wizard’s lessons or copped to its influence. More to Patti’s point, new generations of artists, from Gen X to Gen Z (multiple genres and several electronic subgenres alone, from Daft Punk to Com Truise), have not only attested to the record’s legacy but have given it a whole new life through their music.

Which is to say that as much as these plague times call for a nostalgic diversion, and we do indulge to be sure, this interview isn’t just flashback with a legend, it’s a testament to how one artist couldn’t be pinned down to one style or genre of music and ended up putting his imprint on a myriad of them, becoming one of the most prolific around. But if you want to about his impact on rock and pop, you’ll only scratch your head wondering why he’s not already in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. This interview, however, isn’t meant to only appeal to Rock and Roll Hall of Fame-geared geezers, Todd knows, he’s made plenty of music (still does) to drive this fan base crazy; having always had a penchant for the cutting edge and no interest whatsoever in just being a “classic” rocker, he’s tried his hands at pop, punk, new age, lounge, even cyber- techno-grunge-rap––It was the 90s, kids, and for No World Order, he beat Prince to the name-change punch (he also played a symbol guitar before the Purple One) going by TR-i, the “i” for interactive, since it was the first interactive music release on a Phillips CD-i.

And Rundgren hasn’t confined himself to creating music: he’s also a video artist, music video producer, software developer, author, professor and philanthropist, to name a few of his side-gigs. And yes, while this tour and this interview does look back at his now celebrated 1973 album (and other career highlights), Rundgren isn’t content to just collect royalty checks from the artists who have sampled him (like Frank Ocean, Neon Indian, J Dilla, Fetty Wap, Slum Village, Charlie XCX, Simian Mobile Disco, and about 10 more pages of examples on whosampled.com), he’s out there collaborating with them or covering them (like Post Malone, for instance). And when he’s not fronting his own bands, he still finds time to play in other people’s bands, such as The New Cars (which was actually an amalgam of The Cars and Utopia), Ringo Starr’s All-Starr Band, and his recent participation in A Tribute to The Beatles’ White Album, with Mickey Dolenz, Christopher Cross, and more. And now, without further delay, here’s our spirited chat with the wizard and true star.

Music Connection: What can you tell us about the new tour?

Todd Rundgren: In many ways it’s similar to the tour I did a year ago last May. The only difference is on this particular tour instead of doing a random selection of material for the second set we will be doing either side A or side B of A Wizard, A True Star. It’s going to be a bit more work than last time. The last time I came up with a list of maybe ten or eleven tunes and A Wizard, A True Star. I did twelve costume changes in an hour. Since we’re only doing one side each night, but I’ll still average out to about a half a dozen costume changes during the course of it.

MC: Twelve costume changes, that’s a lot of showmanship.

Rundgren: There used to be an expectation of showmanship, and I’m going back to the Beatles, even. If you were Frank Sinatra, at least you wore a suit. When the Beatles first came out, of course, they were all wearing tailored suits and stuff like that. They evolved and their wardrobe changed over the years, from Indian clothes to Nehru jackets, that kind of piqued everyone’s interest in what could be done in terms of other ways to dress. But it wasn’t street clothes. When grunge became a popular format, it was considered arty to wear anything but the normal street clothes, like baggy shorts and a lumberjack shirt. I can see how that worked, but in the end it sort of annoyed me that it was essentially fashionable to make no effort. And there’s always the sort of middle thing, like Wayne Coyne from the Flaming Lips, where he gets inside a big ball and rolls around. Essentially, they put on a big spectacle, which is unpredictable. It’s just like craziness for the sake of craziness and that’s, to me, maybe some sort of ideal. Because it’s not slick in the way a Vegas show is and it isn’t blasé like walking on in your street clothes is, it’s kind of spectacle but with spontaneity and fun to it.

MC: About the “spectacle,” in the 70s Utopia had productions that rivaled ELP, ELO, Earth Wind & Fire, and P-Funk.

Rundgren: You’ve seen the videos of the Beatles (again we use them as a reference point of almost everything) playing in Washington, DC, when they didn’t even have roadies. They had to rotate the drum kit around themselves. And all they had was a couple of amps and people screaming. No fancy lighting, no special effects, nothing like that.

Then as time went on, and live performance became so much larger and more popular, to the point where you are filling Masonic centers, basketball arenas, and eventually stadiums, you had to do something, because otherwise you’re just like this little tiny speck off in the distance. So, in order to engage a larger and larger crowd you started doing larger and larger sorts of effects. Utopia certainly went through that phase when we had a pyramid and a sphinx on stage. And that style of thing was a precursor to the hip-hop thing now, which is lots of special effects and dancers and essentially something like a Vegas show. Something very highly choreographed, exactly the same every night.

MC: Talking about Vegas, on that Ra Tour (1977) you scaled a pyramid that seemed as high as the Luxor, and the drum solo even featured waterworks that predated the fountain show at the Bellagio! We’re talking big!

Rundgren: It was the sheer sizes of the audiences as well. In rock it used to be that if you could fill a high school auditorium you knew you were a serious act. And nobody thought about it, until the hysterical sort of fame and demand for the Beatles that eventually led them to Shea Stadium. People didn’t think in those terms, people didn’t think they could even sell out such a venue, but that was because we didn’t know how popular that kind of music could become. And they were essentially going through the public address system, which [game announcers] would call the balls and strikes on. The Beatles realized that was no fun at all, so they quit playing. The senseless thing is that they missed the opportunity to be able to drown out the audiences so that they could hear themselves, and who knows? They might have gone back to playing live, and stayed together as a group, but unfortunately they broke up before technology evolved.

MC: How do you explain being part of this group of rock stars, such as Alice Cooper, David Bowie, and Peter Gabriel, who all put on a show and experimented with make-up and theatrics?

Rundgren: Perhaps the kids today are not as familiar with Cab Calloway, so to cite a more familiar example, the Beatles were known for shaking their hair and going “woo” in, “She Loves You.” George would do a little two-step, but that was it for the most part. I think the first time I became aware of showmanship in rock was seeing The Who live. It was their first performances in the United States, it was a Murray the K show that also included the premiere American performances of Cream. It was the first time you saw a band and said, “I don’t know who to look at.” Because everybody is a show onto themselves; Keith Moon is back there flailing away like an octopus, you’ve never seen anybody wail on the drums like that before, and mugging the audience, and clowning around with the rest of the band. Pete Townsend is windmilling away, jumping, and jamming his guitar into the amplifier. And Roger is swinging the microphone like twenty feet out and over the top of the audience, and you’re wondering whether he’s going to hit somebody, and he never does. And even John Entwistle is over there with his completely deadpan expression, while his fingers are flying a mile a minute! And the way they dressed, like turn of the century foppery. I’d never seen anyone put so much energy into a performance up until that point, and I thought “Wow! I want my band to be able to do that.” To be able to spellbind in that way, you don’t know who to look at. It was the first time I thought about the showmanship, the showbizzy aspects of the presentation.

Then later came the more theatrical aspects: I remember seeing Genesis for the first time, I think it was Avery Fisher Hall, the first dates they did in the US. Peter Gabriel had this little podium in the middle of the stage, and he would duck down behind it and come up as a different character. Then he’d duck down and come up again as a new character. And it wasn’t elaborate, but giving us a different character to each song influenced me, I guess. The idea that you get into character, you don’t just sing. It’s more like musical theater. And I really sort of appreciated that because growing up my dad was very much into the musical theater and we used to go to summer stock and see Kismet and The Music Man, and stuff like that, where you’re in character for the whole thing.

MC: I found Intersection, the 1972 short film you’re featured in, on YouTube, and it captures the time perfectly. It even has Wolfman Jack in make-up and costume that has him looking as if a future Gene Simmons joined the cast of Cats.

Rundgren: Well, that was one of the high points of my experience around that time. I moved to LA for the year that I recorded Something/Anything? The record made a big splash, and I had a song about Wolfman Jack on it and so I got to meet him, and that was great. And we became really good friends. I would visit him at his home where he had his studio, and I got to watch him actually do a couple of shows. Of course, it got sent down to a transmitter in Tijuana, it wasn’t broadcast from Bel-Air or where he lived. Then Brian Wilson heard the record and I was contacted by his people who told me he wanted to meet, so I met Brian at the height of his craziness. [Laughs] It’s all in my book. [Individualist: Digressions, Dreams & Dissertations]

MC: You’ve been compared to Brian Wilson. Both of you described as musical geniuses, studio wizards, and Wall of Sound-man wunderkinds a la Phil Spector. Something/Anything? and A Wizard, A True Star are reminiscent of Pet Sounds and Smiley Smile or Smile [Rundgren covered “Good Vibrations” in 1976. He’d almost repay the favor in 1995, when his New World Order disc––the first interactive CD release––would inspire its producer, Don Was, to pitch Wilson the idea of releasing a three-disc interactive version of the ambitious, yet scrapped, Smile]. What’s your take on the similarities?

Rundgren: I imagine it had to do with a lot to do with the same things that were affecting Brian.

MC: You mean LSD?

Rundgren: [Chuckles]. Yeah. Maybe. Brian also had other psychological issues that fortunately I have not experienced. Apparently, the drugs exacerbated that, and the result was when I met Brian he had no attention span. First thing he said when I got to his house was, “I have the new Roy Wood single!” And he would put it on and play 15 seconds of it. Then he took it off, ran over to the piano and started tinkling out something, and then 20 seconds after that he was off doing another thing. Whatever the diagnosis, one symptom of it was a really short attention span. And I always had that issue. It was one of the reasons why I always did so poorly in school. But the realization that I had as a result of my mental experiments and stuff was that I was doing things according to a perceived formula. I was doing it the way I thought everybody did it, and likely the way everybody usually did do it.

You always write songs about relationships, and the form is verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, chorus, chorus, chorus. A lot of my influences up to that point were professional songwriters, like Carole King, and on Something/Anything? I wrote “I Saw the Light” in like 30-minutes flat. At the time, I hadn’t intended for Something/Anything? to be a double album, it’s just that once I started writing I fell into this formula and the songs started coming out. People were literally comparing me to Carole King, and I just didn’t want to be compared to other people. I said, “What’s the point of me doing something so familiar that it’s like duplicating someone else? I want to do something nobody else would or could do. It has to be unique to me somehow.” And that’s when I realized that there were all these other kinds of musical ideas floating around in my head and I hadn’t necessarily figured out how to express them, but I wasn’t going to worry about that, I was just going to start getting stuff out of my head.

I was about to start my next record, and that’s how the stream of consciousness-effect of A Wizard, A True Star came about. My attitude was, “If I don’t have a bridge for this song, then the hell with it I’ll just use what I have, and then I’ll just hop into another musical idea until I’ve exhausted that one.” And so, there were songs that were less than a minute and some went on for seven minutes, I just kind of threw out all of the formula aspects, the verse chorus verse chorus bullshit, and that became more of the character of how I would write after that. I would try and find something that other people were less likely to do and try and figure out a way that I could and try and express something that was not just a typical insincere “I love you, you broke my heart,” especially if I wasn’t in a relationship where I wasn’t getting my heart broken. That was part of my inspiration for all these songs was the one relationship that I had in high school. Here I was five years out of high school and I’m still writing about it.

MC: Daft Punk used Wizard’s “International Feel” for their 2006 film, Electroma. Do you remember that?

Photo by Rich Levine.

Rundgren: I do. I have a weird Daft Punk-related story: A couple of years ago, “Get Lucky” was the Number One song of the year, and I got invited to the Grammys by a Japanese satellite TV company. Ringo [Starr] was getting an honorary lifetime Grammy, and since I had been touring with him they wanted me to do some color commentary on the whole thing, especially the Ringo part. I was on site, and got to watch some of the live performances, then I got invited by Daft Punk to go to their afterparty, and that was also the evening that I realized what a terrible person Paul McCartney is. I had my suspicions before. I was there with my wife and youngest son, and after a while we realized that this is going to be one of those celebrity hangs and I don’t really fit in to that stuff very well, so I decided, okay, it’s time to leave.

Then I see one of the guys from Daft Punk, and he’s talking to Paul McCartney. Paul is facing me, the guy from Daft Punk has his back to me, and I just wanna go over and say goodbye and thank him for inviting us to the party, but there’s a security guard standing next to Paul off to the side, while he and the guy from Daft Punk were talking. I’m just waiting for them to take a break so I could say goodbye, and the security guy starts giving me a real hard time. He doesn’t’ know who I am. Paul knows who I am, because his wife [Linda] took pictures of me, and I saw his wife and him at the gallery show, plus I’ve also spent time with them; I’ve hung around with them at the Plaza Hotel one time for a couple of hours, and oddly he seemed like he had no sense of humor. Like he doesn’t understand irony or anything or sarcasm. But in any case, he just stood there watching the guy hassle me the whole time and did nothing, just did nothing. And after they were done with their conversation, I told the security guy, “I don’t want to talk to THAT guy [Paul], I know who that guy is, and I don’t want to talk to him.” And after they ended their conversation, I got to say goodbye to the Daft Punk guy. But I realized that night that Paul was going to let the guy kick me out, when he knew who I was. All I’m saying is, I’ve known this about him. It was just an interesting anecdote, I guess.

MC: It sure is. I bring up Daft Punk, because you are as influential to the electronic world as you are to the rock world. Something/Anything? and A Wizard, A True Star are seen as blueprints for auteur producers.

Rundgren: I do know that there is a connection with Daft Punk and also some younger artists. There’s a Norwegian DJ named Hans-Peter Lindstrøm [producer known for his space disco track “I Feel Space”] who asked me to do a remix for him a couple of years ago, and then a few years ago we did a whole collaborative project [Runddans, from 2015, recalls elements of Rundgren’s 1975, album Initiation] with another guy, Emil Nikolaisen, and it was a three-year project of us just sending stuff around to each other. When it came out, it created something of a stir because it was a big long sort of chunk of

music that is spread over four sides of a double LP, with no breaks, other than the sides.

I went into the studio with them and they had acquired a piece of equipment [and EMS Synthi Hi-Fli] that I had back when I was doing A Wizard, A True Star and the album after that. It was a thing you plugged the guitar into, and it was a pitch-to-voltage converter that made synth sounds come out. And they actually found one, and they said “We want you to reproduce the sounds you made on that record,” which I actually attempted to do. We recorded a couple of sessions: One session they told me all the things they wanted me to do, and a lot of it was things that I’ve done before, and the next session I told them what to do. I said “Here I want you to go out there and just play the piano, but I want you to play in key around this and then I’m going to double the speed up real fast.” And so we were just trading tricks and stuff and messing around and it tuned into a three-year international collaborative project.

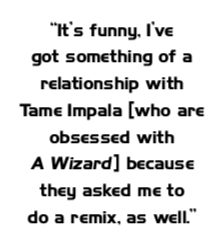

It’s funny, I’ve also got something of a relationship with Tame Impala [who are obsessed with A Wizard] because they asked me to do a remix as well. And I’m trying to talk [band leader] Kevin Parker into doing a collab for my new record, if I could just get him to open up a little time.

MC: To what do you attribute all these electronic, pop, and hip-hop artists diving into your

old records and either emulating or directly sampling you?

Rundgren: I think a lot of it also is when you get to the point, kind of, where I got to, which is you realize you’re making the music that other people are making and you know a lot of it is sort of imitative and formulaic, and you want to do something different. So you go out looking for influences. And since you can’t look into the future you start looking into the past. And that’s the great thing about YouTube and the internet, all that stuff is archived somewhere in there, you just have to have the motivation to go out looking for it. I think a lot of these younger artists get to a crossroads for themselves and they say “I need new influences and I’m not getting it from my contemporaries, because everybody’s trying to do the same thing.” So they go back and look for unusual artifacts of the past to find new influences, and I think that’s the phenomenon, because I have experienced that myself.

MC: What did you find yourself going back and “rediscovering?”

Rundgren: When we transitioned from vinyl to CD, the Japanese really jumped on that whole thing, they would go back and find any obscure record they could possibly find and turn it into a limited run CD. There used to be a record store in Tokyo and it was essentially seven stories of CDs, and you would find music there that you wouldn’t find anywhere else in the world. I remember getting really interested not only in all the obscure records that you would never find in a record store anymore, but getting into what became known as bossa nova again, and that’s what inspired me to do the With a Twist record. I started buying all this cocktail music. All of Frank Sinatra’s records from the Capitol years, Esquivel, Martin Denny [the “Father of Exotica”], and Arthur Lyman. All of this exotica music and Space Age bachelor pad stuff.

Esquivel was really great because he would also do technological things that no one else would attempt. When he was in the midst of his recording career, stereo came about and he said “I’m going to make the most stereophonic records anyone has ever heard,” and instead of putting the orchestra all in one room and miking them up and trying to get separation, he put them in separate studios. I don’t know how he got them to sync-up, because he wouldn’t even have the musicians playing in the same room, but he would get the most ridiculous stereo separations. Some of his records, when you listen to them on headphones, are just mind-bending. And that’s what influenced me to take all my old material and do it in a bossa nova and exotica style for With a Twist.

MC: You’re also an inventor and software developer. What is the synergy between being an inventor and a musician?

Rundgren: I got involved in the computer community, as it were, in mid ‘80s. I was living in Woodstock and I taught myself how to program the computer. I was very much into video, and the first thing I did with my computer when I learned how to program was make a Paintbox program. I have seen one at a place called the New York Institute of Technology. The professors there were spearheading computer graphic development with people like Alby Ray Smith, who went on to found Pixar, and Ed Catmull, and names that went on to found ILM. All of these people went on to essentially develop the computer graphics industry that we know today.

I met all these people really early on, and after I finished making my own Paintbox program for the Apple II Plus I was out in California and I thought why don’t I show it to them to see if there’s any interest? It was one single-story building in Cupertino that took up a half a block. I was in the room full of their head engineers; Andy Hartsfield was from Philadelphia and knew who I was and knew I was a musician. I started my demo for him, and Steve Jobs came in and looked at it for a while, and he said, “We’ve got this software distribution program we're thinking of starting for third-party software developers called Special Delivery Software. And we’re going to come out with a graphics tablet of our own (essentially a big square thing with a pen and you draw on the surface of the pad and it comes up on the screen).” And so Apple distributed the program that I wrote. Unfortunately, their hardware device that it ran on failed its FCC emissions test and, essentially, they never sold a device that the software ran for. [chuckles]

That’s how I first got involved with computers. And I became something of a personality in Silicon Valley and started getting invited to hackers conferences and things like that. And through this I discovered that almost every computer programmer was either a music fan or played a musical instrument. And that a lot of them had bands of their own that they would do in their spare time when they weren’t computer programming. I had a band, and when I wasn’t playing with the band I would program for the computer, and they would program computers, and when they didn’t have to do that they would play in a band, so there’s something about that. There’s a connection. The mathematical mind drifts toward solving numerical problems and listening to music while writing programs is a way to draw on the same part of the brain in a way, over time. We learned a lot more about how the brain works and how music affects it.

MC: On the topic of how music affects the brain, maybe this is a good segue to talk about your passion as a philanthropist?

Rundgren: I started a foundation called the Spirit of Harmony. Essentially my fans goaded me into it, but I decided that the purpose of the foundation should be to bring a formal musical education back into elementary schools. When I was growing up, they actually had musical instrument programs. You could rent an instrument and then once a week someone would come to the school and give the kids lessons. But, over time, as funding has dried up for extracurricular programs, usually music programs were the first to go.

In doing the research while establishing the foundation, I learned of a professor at Northwestern University outside of Chicago named Nina Kraus, and she took it upon herself to start doing empirical research on the effect of music education on plastic minds––in other words, brains that are still developing. And she generated a lot of empirical evidence that musical training while the brain in still developing actually changes the way you process sounds. You hear sounds differently than other people do. And it’s something that comes naturally to musicians and possibly people who are into numbers and math and computer programming concepts.

When a normal person, let’s say a musically uneducated person, listens to a record of a band playing they hear the whole thing. It all comes at them at once. And they may be able to say, “That’s a drum” or “That’s a piano,” but they can’t pick out what the separate things are doing musically. What happens when you get formal musical education is that you learn how to focus on those individual components that go into the sound, and that essentially gives you the ability to process sound differently than the average person does in a beneficial way and in a permanent way and so that it will affect you for the rest of your life.

For instance, if you are in a crowded room full of people and you are trying to listen to one person in a room full of people who are all talking at once, the change in the way that you process sound enables you to process that person’s voice and separate it out from the background noise. There’s something that goes on in the brain that understands music and potentially the person that understands the mathematics underlining and it could be trained. You can learn to do that. For me, and probably for some other people (and some of them will go into music and some will go into mathematics), it’s already there. It’s already built-in. Because that was something that my parents noticed about me in the very beginning, I could pick out melodies by ear.

MC: This connection between music and math and science reminds me how Boston’s Tom Scholz went to MIT, Gary Numan is into aviation, and Jeff “Skunk” Baxter worked on ballistic missiles. . .

Rundgren: Now he’s CIA. Also, there’s Brian May, who is an astronomer.

MC: Your upcoming tour also has a technology angle, too––you’re going to let fans decide the setlist via an app?

Rundgren: We’ll play mostly two nights in each city, so obviously we’ll do one side one night and the other side the next night. But in some cities, we play three nights and there’s cities where we only play only night, so we are developing an app so that the audience can vote on which side they want to hear on that particular evening. And then it will also allow them to chat with each other about the question of what they what to hear or anything else they want to chat about and also be able to do some shopping or something like that for some limited-edition items. So it’ll be an app that works only within the confines of the gig, because we will be running the network that you have to connect to in order to vote or to chat or any of that stuff. Right now I’m developing the app, and we’ll get somebody to do the porting of it and ideally everyone will have enough lead-time so they can download the app.

MC: Can you talk about some of the great records you did as a producer and for Bearsville Records at Bearsville Studios near Woodstock, New York?

Rundgren: I did some recording in Bearsville Studios, but most of the acts I would do in my own studio, which was up in nearby Lake Hill, in a small barn on my property. One significant exception to that was Bat Out of Hell for Meatloaf. We did that in Bearsville Studios, and it was recorded all live.

MC: Sparks are a unique and eclectic band that you produced. Did you find a kinship with them or what did you see in them?

Rundgren: They were just different from what everyone else was doing, and if you go back and listen to that first record, it’s very quirky. [Chuckles] It’s just a very quirky record. The first Sparks album, which was actually Half Nelson, we recorded at I.D. Sound in LA, where I did my first three records and both Nazz records. But a happy postscript to that is that I’m doing another collab record and I’ve got a Sparks song on it. So there will be new Sparks featuring me.

MC: What about Steve Hillage, a name that might be a bit obscure to some? Hillage, you, and Utopia were really pushing the envelope of synthesizers, technology, proto-electronica/EDM, and new age concepts. And some members of Utopia appear on L, the 1976 Hillage album you produced.

Rundgren: Well, we did that up at the studio at my house. He actually slept in the studio, because there was a bed in the control room, and he rearranged all the furniture in the studio, because he was into this “the head of the bed had to face north” or something like that. So, he was moving the furniture around so the bed would face the right way. That made things a little less convenient in terms of working. But he had to record things on certain days, like when there was a full moon. It was a very mystical experience. In fact, I don’t think he’s that mystical anymore, but that was back when he was aligned with Hawkwind, Gong and other sorts of hippie musical collectives. The record was really successful and critically well received, and the funny thing is that Steve eventually evolved into an EDM producer.

MC: A personal favorite The Tubes’ Remote Control, 1979. There you not only produced but wrote. Can you talk about that bleed-over where you sometimes go from producer to co-artist?

Rundgren: My style as a producer was not to Svengali somebody into a sound that I had, you know? A lot of producers were more noteworthy for the sound they got. My style is generally to just provide what’s missing. If the band has great songs and lyrics and everything like that, fine, I’ll just worry about the performance, and keeping an ear on the performance and the sound. But if they’ve got issues with the material, like they don’t have enough of it, or they haven’t finished the words to it, and we’re already in the studio, then I would essentially step in and start writing and things like that. And the problem with that is more of my fingerprints would appear on the final product then were supposed to be there.

It’s really supposed to be about the act themselves and not about me. So it was actually after that record that I changed the way that I work and

said, “I have to stop writing for the artist,” and so instead of doing that, I always insisted that the artist demo all of the material that they intended on having on the record. And that I hear it first before we schedule time in the studio. So that essentially got me out of writing too much on behalf of the act that I was working on and therefore making a record sound like their own.

MC: You don’t hear a distinct Rundgren sound on the New York Dolls’ debut record you produced. It’s a masterpiece of proto-punk/glitter rock, and yet, it’s much maligned, with the band and critics saying that they only got it right on the second release. So, what happened there? [Todd would be vindicated as he was asked to produce their 2009 comeback album Cause I Said So]

Rundgren: You know, it’s only what you could make. That experience was like herding cats. You were just trying to catch moments when everyone was focused long enough to get through a whole take, because the studio was always like a circus. There was always groupies, people bringing drugs in. Rock critics saw the band as the saviors of old fashioned rock & roll, but it was more or less chaos all the time, and just trying to get a take where everyone was focused was the most difficult part about it.

What you’re hearing in terms of the record is fleeting moments, it wasn’t like we would do, like, eight takes of a song, we’d be lucky to get through a whole take. When they got to the second record they were very much influenced by the milieu that they grew up in and that’s why they wanted Shadow Morton to do the second record because he had done the Shangri-Las and they wanted the record to sound like the Shangri-Las, but apparently he was in the throes of some sort of addiction and they would often find him passed out on the console, so I’m not even sure how they finished the second record. And then after the second record, of course, they all started dropping like flies.

MC: You talked about trying to enlist Tame Impala’s Kevin Parker for a new collaboration, but I read an interview with you where you said something to the effect that you wouldn’t be making anymore records because of the state of the music business today. Did you change your mind?

Rundgren: By “records” I was referring to LPs. Listening habits have evolved past the long-form. It’s like going back to when most artists focused on singles and then compiled them into “albums.”

MC: The first time you graced the cover of Music Connection was in November ’85. Obviously so much changed in the industry since then, so what would tell a new artist today?

Rundgren: For a musician, things haven’t changed too much in 20 years: Make music on your laptop and distribute it on the net, and build up and audience that will show up live or pay for a stream. It’s hard to monetize the recordings themselves, unless you land a commercial, which is why you have to design your own shoes or smell.

Contact Paul Maloney, [email protected]

Cover photo by Hiroki Nishioka.