Bob Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song was just published by Simon & Schuster. The Philosophy of Modern Song is Bob Dylan’s first book of new writing since 2004’s Chronicles: Volume One—and since winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016.

Dylan, who began working on the book in 2010, offers his extraordinary insight into the nature of popular music. He writes over sixty essays focusing on songs by other artists, spanning from Stephen Foster to Elvis Costello, and in between ranging from Hank Williams to Nina Simone.

He analyzes what he calls the trap of easy rhymes, breaks down how the addition of a single syllable can diminish a song, and even explains how bluegrass relates to heavy metal. These essays are written in Dylan’s unique prose. They are mysterious and mercurial, poignant and profound, and often laugh-out-loud funny. And while they are ostensibly about music, they are really meditations and reflections on the human condition. Running throughout the book are nearly 150 carefully curated photos as well as a series of dream-like riffs that, taken together, resemble an epic poem and add to the work’s transcendence.

News from Simon & Schuster further illuminates the title.

“In 2020, with the release of his outstanding album Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan became the first artist to have an album hit the Billboard Top 40 in each decade since the 1960s. The Philosophy of Modern Song contains much of what he has learned about his craft in all those years, and like everything that Dylan does, it is a momentous artistic achievement.”

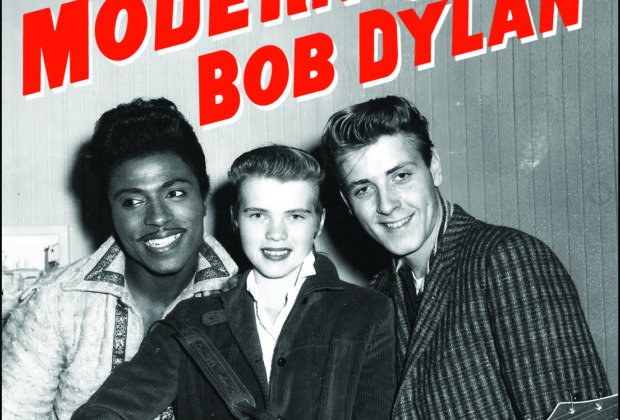

A 1957 photo of American singers Little Richard, Alis Lesley and Eddie Cochran in Australia is the cover image of Bob Dylan’s book The Philosophy of Modern Song. Both Bob Dylan and Eddie Cochran recorded at the landmark Gold Star Recording Studios in Hollywood, California.

Little Richard once visited the same temple of sound, cautioning Love’s co-founder Johnny Echols “not to give your music publishing to a record company.”

Paul McCartney, as a 15-year-old performed a version of Cochran’s record “Twenty Flight Rock” as the first song when he auditioned for John Lennon on July 6, 1957 in Liverpool.

“For Doc Pomus” graces the title page of The Philosophy of Modern Song.

TunesmithPomus, along with collaborator Mort Schuman, were one of the most important and influential songwriting teams from 1958-1965, second only to Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. Pomus supplying the lyrics, Schuman composing the melodies for over 500 songs.

“Mort Schuman was an anomaly when we first arrived in New York in ’64,” reminisced record producer and author, Andrew Loog Oldham, who managed and produced the Rolling Stones during 1963-1967. “The Stones went to The Apollo and Harlem, I went to Mort Schuman, who was dating a late arrival to The Avengers. I witnessed a great songwriter who had assimilated and become so many of the cultures America rejected and turned that metamorphosis into the American art of song, a magic to be embraced forever.

“Lou Adler, Seymour Stein, and Leiber and Stoller had it, so did Paul Simon. To be born into a world that observed and worn, would provide the precious few with a productive future was a wonder to behold. It didn’t happen in England until the Smiths, before that it was merely a case of escaping from the non-future we were offered.”

Personally, and professionally, I have a distinct socio-geographical relationship with a handful of selections Dylan chose for his endeavor.

Over the last half century, I’ve interviewed songwriters, record company executives, arrangers, record producers, music publishers, and artists about some songs Dylan examines and reminds us about in his 2022 expedition.

“All of us, as singers and performers, keep those great songs in the pipeline so they are not forgotten,” emphasized Howard Kaylan, of the legendary pop and rock group, the Turtles in a 2013 interview.

“It doesn’t have to be a great Bob Dylan song or a Tim Hardin song or even a great Leiber and Stoller song. If it’s great and forgotten you kind of feel like you are a missionary as far as getting those things to the public.”

“I thought who would think in their wildest imagination that Tin Pan Alley was a real place,” marveled Robbie Robertson in our 2017 interview. “The Brill Building. And then Donnie Kirshner’s thing. All of it was actually in a place you could go. And the doors were golden when you walked in. And inside there in all these rooms were people who wrote songs and sent them out to the whole wide world.

“I had such a respect and a connection feeling for these people. And I knew Doc and Mort. Doc and Mort remained friends. One of the things that I really took away from the Brill Building were friendships with Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman and Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller.

“Anyway, one of the things I really got from them, because the obvious thing was that they tapped into something that felt good. But it had to feel good. The song could be about anything but it had to feel good. And I was like. ‘Wow…’ It would be one of the guys sitting at the piano playing. ‘Let me think of something. What about this?’ And they would start to play something. I was studying. I didn’t know what the song was about but it feels good. So, I just thought coming in that door, coming in the back door of something, that when you start this thing if it doesn’t feel good then stop right now. ‘Ah ha. That’s something.’

“Then, the other door was Bob Dylan. Who it wasn’t about that. It was about emotion and an energy. But it was really about saying something. It wasn’t about ‘these words could be anything.’ No. No. It was specific. So, to me it was rebelling in a beautiful way against this other thing.”

The songwriting team of Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong wrote two Motown label releases Dylan highlights in his study: “Ball of Confusion” by the Temptations, and Edwin Starr’s “War,” both produced by Whitfield.

“Norman to me was probably the most underrated of all the producers, because he was producing by himself,” suggested Berry Gordy, Jr. one afternoon in 1995 inside his Bel-Air mansion. “And he would deal with different sounds, different beats, change with the times and write his stuff, and also Barrett Strong would work with him as a writer on many of his things. Norman was innovative and he had fire. And he had a different kind of style.

“His beat was different and could go from ‘Cloud Nine,’ ‘Psychedelic Shack,’ ‘Papa Was a Rolling Stone,’ to ‘Just My Imagination.’ He was sensitive and I think he could do so many different types of things. Then he’d come right back with ‘War’ and then ‘Ain’t Too Proud To Beg.’

“He could take one chord, like on ‘Papa Was a Rolling Stone,’ and play the same chord and do all these different beautiful melodies and things that many people could not really imagine this guy doin’. And I would watch him and he did it all by himself as a producer.

“He would work with five guys in the Temps and he would change leads on each one. He would pick the right lead for the right song, ya know, and he’d utilize all five of those leads in a song that was just incredible. When I listen to ‘em today, now that I have time to listen to ‘em, I’m saying, ‘Wow!’ This guy was probably the most underrated producer we had.

“Whatever it is, a great song is a great song. That’s all it is. Let’s make sure we have great songs. I started as a songwriter. I love songs, so you know, that’s a hobby.”

Bob Dylan comments about Elvis Costello’s “Pump It Up” in The Philosophy of Modern Song.

In 1998, I conducted an interview with Costello for the now defunct Musician magazine.

“I think the thing about it is that rock ‘n’ roll had two effects on music. One was one of tremendous liberation, and the other one was a license for a lot of idiots to decry the efforts of more craftsman-like writers, and to suggest that there was a barrier that came up in 1955 like the Iron Curtain going down, and everything after that is justified, and everything before it isn’t. And in recent times, as you see, a lot of kids now are hip to swing music again, and the fact that they may understand it in a kind of cock-eyed fashion or whatever it is they focus on for music, from the richness of musical history, I think it’s a healthy thing that they don’t think just rigidly in terms of like one strain of music to the exclusion of everything else.

“Because the great thing about growing up in England in the sixties is that you could listen to the Beatles synthesizing Chuck Berry, the Everly Brothers, the Miracles, and then on the same radio station there would be actual Tamla-Motown artists; and then Burt Bacharach’s records came out, and all of this stuff is going in my head at the time when I’m just getting my musical ideas. It’s all going in my head like at a million miles an hour. That’s the most exciting thing. It is deeply rooted.”

Another entry in the Dylan volume is “Key to the Highway’ by harmonica player/singer Little Walter, penned by Big Bill Broonzy and Charles Segar.

Dylan writes, “In a lot of people’s opinion a greater singer than anyone on Chess Records…Little Walter could take other people’s ideas and make them his own…He is also known as the electric blues harmonica originator, the master craftsman and the prime mover.”

“Little Walter is the truest genius of all the Chess artists,” underscored Marshall Chess in a 2010 dialogue. “Because he invented and perfected a new way to play the harmonica, and did it with tremendous creativity and talent. Very much like Hendrix with guitar. They’re exactly alike. Miles Davis considered Walter a genius. Hendrix considered Walter a genius.”

The Grateful Dead’s “Truckin’” earned a spot in the Dylan parade. Composed by Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir and Phil Lesh with lyrics by Robert Hunter. Produced by Steve Barncard and the band.

In 1976 I spoke to Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead about the San Francisco music scene and band philosophy.

“We’re serious. One of the things you could say about all the bands that came from San Francisco at that period of time was that none of them were very much alike. I think each of us has dealt with it in various ways. For me, I know what I’m supposed to do, and I’ll do what I’ll have to do to be able to play. I think almost all the people I’ve known around this area, involved around the music scene, have been faithful to that thing. They’re all kinds of things happening, but it really has to do with what you are into.

“Right now, the San Francisco music scene is deeper than it ever was, in the sense of any night you can go to 14 or 15 places in the Bay Area in a radius of 50 miles and see something really good. Not only that a lot of different kinds of music.

“Everybody knows who they are. No matter what you read about you in the paper, you know who you are. You don’t get any special breaks at the gas station. You can either be sucked in by that stuff, in which case it just eats you, or else just realize there’s a difference between what you read and who you are. I always did. It works beneficially. Doing things with other people, you can appreciate the uniqueness of each situation a little better.

“It’s not judgmental. You can’t deal with it in a yes/no kind of fashion. For example, my band is a band that could best be described as consonance and harmony. Conceptually, everybody in the band thinks pretty similarity. In the Grateful Dead it’s a situation in which almost no two people have the same conception musically; which makes it harder. Nobody gets their way. However, what we all respect about that situation is that there is a potential of a larger central viewpoint which none of us, individually, are capable of perceiving, but which we all add to because of the diversity and the conflict.”

Dylan ruminates abut Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night” in chapter 62. This 1966 hit single was arranged by Ernie Freeman and produced by Jimmy Bowen at the famed United Western studios on Sunset Blvd.

In 1998 I met up with radio and television personality Dick Clark and we talked about Frank Sinatra.

“Well, there are certain people who are very influential in music throughout the years. Go back to the days of Rudy Valee, who was the first crooner, Bing Crosby, and people followed. Sinatra learned his style, I’m told, by listening to Tommy Dorsey play a trombone. If you listen to the way he crafted a ong, it’s very ‘trombonish.’ I’m a great admirer, because he influenced so many people. I grew up with him when I was a disc jockey at an AC station in the days when it was ‘middle-of-the-road.’ I played a lot of Sinatra. I was a Nelson Riddle and Billy May fan.”

Drummer Hal Blaine and guitarist Glen Campbell are heard on “Strangers in the Night.”

“There was a song that we did and he wanted to show that he had an operatic type voice,” Blaine told me in a 2007 interview. “Just a big voice. Like Elvis. That’s all there is to it. He was a one of. People who generally become famous are one of. Sinatra was Sinatra and Elvis was Elvis.

“The Wrecking Crew [then known as Local 47 Musicians Union members] could lock in with anybody. When we finished, we had to go out and do another session. I might have had two other gigs that day. Our job was making hit records and we loved it.”

“On the Sinatra session,” volunteered guitarist Campbell in a 2008 interview, “Barney Kessel and Tommy Tedesco were great readers. A lot of the session musicians lived in Laurel Canyon. The Wrecking Crew as they were later known, could play anything. You would cut with the Monkees, Beach Boys, and Sinatra.”

“My father really loved being booked on Frank Sinatra dates,” added Denny Tedesco. “Plus, Frank had the sessions catered by Chasen’s restaurant.”

During 2021, I did an interview with Nancy Sinatra, who besides her own stellar recording career with producer Lee Hazelwood on the Reprise label, would often attend recording sessions of her father Frank at United Western.

“I think we learn from everything as we go along. Just about anyone will tell you that the phrasing is solely dependent on the song and the lyrics. At least it should be. Although I know there are people who just sing on the beat no matter what. It’s a shame they don’t experiment a little bit. I don’t think I copied anybody.

“The musicians were absolutely breathtaking to watch,” beamed Nancy. “You’d come into a studio and sometimes you’d have written charts, most of the time you would have chord sheets and they would create almost everything. The arrangements grew as time went on and of course when they worked with my dad or Dean [Martin], people like that, they had charts to read.

“Glen [Campbell] could never read. He listened to the run-throughs and he was so quick he picked up immediately what he had to do and it was without a hitch, you know.

“The guitar section was phenomenal. They were so great. United or United Western was my second home. Great memories, but they’re all a blur. [laughs]. The room was filled with musicians. It’s a long time ago…The engineers were great and my experience was with Eddie Brackett. Eddie was just brilliant. And he knew my voice quickly and he enhanced things beautifully. Jimmy [Bowen] was the person who suggested I work with Barton [Lee Hazelwood].”

I was delighted that in chapter 25 Dylan raved about Johnnie Taylor’s “Cheaper To Keep Her.” In his text, Dylan tells us “Divorce is a ten-billion-dollar-a-year industry…Or, in this case, Johnnie Taylor saves you a hefty legal consultation fee by telling you that it’s cheaper to keep her.”

I first discovered Johnnie Taylor when he was part of a gospel group with Sam Cooke in the Highway Q.C’s, and eventually hired to replace Cooke in the Soul Stirrers.

In 1962 Taylor inked to Cooke’s Hollywood-based SAR Records label and recorded a regional turntable hit, “Rome Wasn’t Built In A Day.” After Cooke’s death in 1964, Taylor moved to the Stax label, and scored with “Who’s Making Love,” followed by “Cheaper To Keep Her,” written by Mack Rice, and produced by Don Davis.

Singer/songwriter and guitarist Bobby Womack first came to prominence in the 1950s as part of the Womack Brothers, a gospel group. They were signed to Cooke’s SAR label.

“I met Dee Clark when we did tours together with Sam,” Bobby mentioned in a 2008 interview we conducted. “He had a beautiful voice. Johnnie Taylor had star quality and he could sing. Curtis Mayfield was a hell of a talent. Everybody knows that. He was before his time, really. He wrote some great stuff with the Impressions to Jerry Butler and for so many artists.”

In 1972, movie director Mel Stuart lensed Johnnie Taylor inside a funky club near South Central Los Angeles for his epic WattStax documentary. “I had Johnnie singing ‘Jody’s Got Your Girl and Gone.’ The feeling and intimacy of that club, and the heat generated by that guy. Certain people have star quality. And you can’t get it. You either have it or you can’t acquire it. You have it or you don’t have it.”

And this cat had it. I met and interviewed Johnnie decades ago in Hollywood and also got his autograph for drummer/writer Paul Body.

I’ve got to give Bob Dylan kudos for having poet/songwriter and political activist John Trudell’s “Doesn’t Hurt Anymore” in The Philosophy of Modern Song lineup.

Dylan devotes four pages to the saga of John Trudell, who was a Santee Dakota Indian and served as chairman of the American Indian Movement.

Dylan cites “Doesn’t Hurt Anymore” from the album Bone Days.

“The space between it and Hank Snow’s ‘I Don’t Hurt Anymore’ is profound. One is sort of a gaudy statement about teardrops drying, and the other will tear your heart apart…Take a moment-read a little more about John Trudell than what is offered here. He deserves it. And after you do, seek out his music. A good place to start would be AKA Grafitti Man, full of simple direct performances with John accompanied by his Oklahoma soul brother Jesse Ed Davis.”

I met John Trudell on several occasions. I was first introduced to him in 1984 by Jack Nitzsche and Buffy Sainte-Marie at the Comedy Store in Hollywood where Jack put together a band and the musicians performed for a Free Leonard Peltier benefit.

I subsequently arranged a couple of college radio interviews for John when AKA Grafitti Man was issued on cassette. In 1986 I booked him for a reading at McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica with Jello Biafra of the Dead Kennedys. The venue was packed for this inspirational verbal platform of Indian and punk tongue. Later that year I presented a show with Trudell and Kiowa/Comanche guitarist Jesse Ed Davis at Be Bop Records in Reseda.

After the event, I told Jim Keltner how terrific the gig was. Jim had recorded in 1971 with Dylan, Davis, Carl Radle and Leon Russell, and together they participated in the Concert for Bangladesh. Keltner then sighed, “Jesse Ed was the only guitar player who ever made me cry.”

Bob Dylan is our tour guide audio librarian in The Philosophy of Modern Song. His writing about hand-picked copyrights is insightful, highly enjoyable, educational and continues the beatific aspects of his observational skills while reminding us about the impact and durability of 66 songs and the recording artists who did them.

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For November 2021, the duo wrote a multi-narrative volume on Jimi Hendrix for the publisher.

In 2015 Palazzo Editions published Harvey’s Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, and Neil Young, Heart of Gold published in 2016.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Eddie Kramer, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Christopher M. Allport, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

In 2015 the University Press of Mississippi published a Harvey Kubernik interview with Oscar-winning director D.A. Pennebaker in their book series, Conversations with Filmmakers, edited by Dr. Keith Beattie.

This century Kubernik has lectured and conducted courses on the music business and music documentary films in Southern California at UCLA and USC. In 2017 Harvey appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio in their Library & Archives Author Series.

Kubernik’s writings are housed in book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and the Ramones’ End of the Century. and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival).