“If it were not for Dylan and his manager Albert Grossman I might not be here. I worked for them for 10 days in January of 1963. I met the Rolling Stones in late April of the same year. The first 20 minutes in their hotel room and I wanted in. The magic between them, it was a working marriage that informed me and let me know what might be possible.”

--Andrew Loog Oldham, record producer, author, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductee.

There are aspects about Bob Dylan’s journey, and career machinations that I’ve found intriguing, informative, daring, educational, and inspirational, as well as his business acumen, probably necessary for him to survive and thrive in “the music business,” benefitting all of us who have heard him or read his words on a page.

On his 80th birthday I’m thankful for this confident, charismatic, consummate wordsmith, this multi-faceted Shakespearean genius, a musical equivalent of “Sammy Glick" on occasion, who, plying his trade at the Columbia lot instead of the Paramount studio, wrote about our joint transformative incidents, human drama, location and destination. Dylan is a natural successor to navigation guides and location scouts Sinatra and Elvis.

Over the last 50 years while conducting nearly 2,000 interviews, I asked a yearly question to them about Bob Dylan.

Acknowledging both Dylan’s 80th birthday May 24th, and examining his vast influential body of work, I culled my 1972-2021 archives for reflections and observations from interviewees and their email correspondence the last half century.

Johnny Cash: I became aware of Bob Dylan when the Freewheelin’ album came out in 1963. I thought he was one of the best country singers I had ever heard. I always felt a lot in common with him. I knew a lot about him before we had ever met. I knew he had heard and listened to country music.

I heard a lot of inflections from country artists I was familiar with. I was in Las Vegas in ‘63 and ‘64 and wrote him a letter telling him how much I liked his work. I got a letter back and we developed a correspondence.

We finally met at Newport in 1964. It was like we were two old friends. There was none of this standing back, trying to figure each other out. He’s unique and original.

I keep lookin’ around as we pass the middle of the ’70s and I don’t see anybody come close to Bob Dylan. I respect him. Dylan is a few years younger than I am but we share a bond that hasn’t diminished. I get inspiration from him.

Richard Williams: In 2009 Bob Dylan released his 33rd studio album. It was called Together Through Life. I love that title because it describes how I feel about him. We’re not related, so he’s not my brother. I’ve never met him, so he’s not my friend. I wouldn’t burden him with the role of prophet, priest, shaman or griot. But he’s been with me since the summer of 1963, when I first heard The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, his second album, then hot off the presses. I was 16 and he was 22. That’s a long time ago. Sometimes it feels like it (time passes slowly up here in the daylight) and sometimes it doesn’t (time is a jet plane, it moves too fast). So I’m me, and he’s Bob Dylan. Together through life.

Jackson Browne: What Bob Dylan did for me, everybody and our generation it will never have to be done again, you know. The way he opened up our thinking and our feeling and our view of the world only has to be done once. Maybe it’s done in other fields like film and painting and other art. As a people we’re constantly growing, expanding but the changes that Bob Dylan brought to rock ‘n’ roll and songwriting are permanent. They’re part of us. People who are just being born into it now are being born into a world that wasn’t that way until Bob Dylan made it that way.

It’s a particular skill to write something in a few words that speaks volumes. It is very difficult to say how I feel and how I think about Bob Dylan in a few words.

Daniel Weizmann Ya know, there's so much to love about Dylan from the kaleidoscopic verse to the heart's melodies, the humor, the romantic feeling, the gallantry, and beyond...but other people have those things too. What makes him stand alone in that unfathomable way is something else, his keen sense of gravity.

Dylan's gravity is Biblical, and obviously, I don't just mean, "he's a believer," lots of people are that. What I mean is, his gravity is the gravity that was there before the modern world--the ancient wisdom of consequence.

When the dude was a young man this gravity of his was jarring and it rocked the world. When he was middle aged, as the world around him reached for new heights of weightless superficiality, his gravity sometimes made him seem a little lost, like a wise man at the opening of a mall. But now that he's golden--and we're living in the land of consequence--we can finally see the burden he carried all along.

Anthony Scaduto: If you are going to get into a superstar level, you have to be hard. In the beginning, Dylan had the bodyguards, the Albert Grossmans. You’re an idol, and it’s the kind of thing they put you on the crucifix for. You have to be protected, or it’s going to destroy you.

Ian Hunter: It’s no secret that I’ve always acknowledged Bob Dylan as one of my heroes. Michael (Mick Ronson) always liked to go to Reno Sweeney’s (a club in New York). One night I said to Mick, “why don’t we go down to the village?”

I took him down to the village. He’d never been there before. We went an all hell broke loose. Dylan was playing next door in a little café. Forty people in the room, and he performed what was to be the Desire album. It was great. There he was. What an electric night!

We were introduced, and Dylan started jumping up and down saying “Mott the Hoople! Mott the Hoople!” Here I was talking to Dylan, and I thought he didn’t like Mott the Hoople by the way he was acting. I didn’t need this shit mocking me. But then he turned round and said, “No. man, I dig Mott the Hoople! “Half Moon Bay” and “Laugh At Me.”

The first thing he did was go to the bar because he couldn’t handle it. The Band was there. Everybody in there I respected. Then the company people came, he went to the bar and proceeded to get pissed. I can’t remember what I said to him that night...

But the two artists I grew up with, Bob Dylan and the Stones (Mick Jagger) were both limited singers. But Jagger was the sexiest singer in the world, and Dylan would make your hair stand on the back of your head, because his voice was so lousy. That’s the truth. I’ve got a lousy voice, and so have Randy Newman and Leonard Cohen. But it doesn’t really matter. I’m conscious of not being a good singer, but that’s just in your throat. I think we all get the message across.

When he got ill a few years back, I was in England, and it hit me like a ton of bricks. I couldn’t believe it. I hardly know this bloke, you know what I mean? ‘Cause at first they didn’t know what it was. They thought he was seriously ill. I’m like, “Oh my God!” I’ve had people die on me. A lot of people died. That really shook me up. I seem to have very strong feelings in another way, a deeper way with that guy. A lot of people do, you know.

Time Out Of Mind I thought it was a great record, but the more I heard it, the better it got. I love the sound of his vocals on it. I wish he always had sounded that way. Oh Mercy was a great record. When I was doing Artful Dodger, I was playing Oh Mercy. He has a great facility for walkin’ in and makin’ it sound like “an evening with Bob.” Most albums sound like from here, there and everywhere. But it’s a mood. You know what I mean? And Oh Mercy is one of them albums. It’s a mood and you can stay in it all the way through.

Michael Simmons: It takes unequalled artistic courage for Bob Dylan to fuel his trips past the exosphere. Most people are sheep following herds into walls, doing what the bosses tell 'em. Dylan listens only to his muse. Happy birthday Bob.

Jim Keltner: At the August 1971 Concert for Bangladesh when George [Harrison] introduced Bob. I stood backstage and Dylan walked on. Jean jacket, kind of quiet the way Bob always is. Bob walked by me on his way to the stage. I had already recorded with him a couple of months earlier, and I sort of knew him.

He walks out there on the stage and puts the harp up to his mouth and starts singing and playing and chills up and down my arms. His voice and the command, it was awesome. And Leon [Russell] decides to go up with his bass for “Just Like a Woman,” and play with him. It was a tremendous moment. It was real dark on stage with a little light for them. Dylan was incredible. Standing in the back in the dark, it was great to see Leon have the guts to get up there.

Kenny Buttrey, who is on the original “All Along The Watchtower” has always been one of my favorite drummers. Every song that I ever heard that Kenny Buttrey played on – which are numerous Bob Dylan, Neil Young and even Linda Ronsdadt records – any song from any era that I heard Kenny play on was complete and perfect. He just had honesty in his playing. Complex but simple.

“All Along The Watchtower” was always one of my favorite songs to play with Neil [Young]. Amazing song. Jimi Hendrix, Neil. Playing it with Neil was always a huge amount of fun because of the way he plays. His sound. The song just allowed him to soar, completely fly. And it allows for a big, massive wide beat. It has so many powerful elements. Playing it with Bob Dylan was the ultimate, of course.

Howard Kaylan: All of us, as singers and performers, keep those great songs in the pipeline so they are not forgotten. It doesn’t have to be a great Bob Dylan song or a Tim Hardin song or even a great Leiber and Stoller song. If it’s great and forgotten you kind of feel like you are a missionary as far as getting those things to the public.

Heather Harris: It's as impossible to envision the 1960s without Bob Dylan as it would be without the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. These artists redefined their respective art forms purposefully, flamboyantly and ingeniously, but only Dylan redefined his fans' lives. Dont Look Back and all Dylan's subversive but eventually universal approaches in his music and lifestyle alerted the 1960s demographic to his fulltime nonconformity, his creativity, his snarkiness, his meaningful protest, his sense of unmet justice and his fun with pop culture, that could also be doable human by human. He created something new, he stood for something new, and you could too.

And, as always, the geniuses make it look easy, which it never is. Dylan's extreme open-mindedness (A Fender Strat versus folkies in '65! Johnny Cash duets in the equally divisive as now late 1960s!) scorched the sensibilities of those hellbent for purity, hence the tales of mixed receptions to his public sea changes like acoustic to electric, folk rock to countrified roots, etc. etc. and, well, everything since.

Subjective asides: 1) as much as I adored and wore out his vinyl albums of Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited, I am equally impressed with his writing, recording and releasing all sixteen utterly engrossing minutes of his "Murder Most Foul" in our otherwise grim and ghastly year of 2020. This emotional epic delivered with clinched-teeth subtlety and all new untamed imagery was just what one expects from our lifetime laureate who turns 80 years old this very May.; 2) Award-winning television comedy writer Merrill Markoe annually reviewed Dylan's outdoor Christmas decorations up until the horrifically destructive 2018 Malibu fire; 3) Word has it that Dylan buys Malibu property and deliberately leaves it fallow (undeveloped,) making him a secret, anonymous, major conservationist. 4) Sirius XM satellite radio's broadcast of Dylan as DJ for consecutive shows was an eye-opener to his wit and expansive music knowledge. Little did I expect The Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band's tunes also to resonate with the mighty author of the Mighty Quinn! 5) He certainly didn't need the money. A true musician's musician, he just must have loved touring his wondrous catalog of songs all these years....

Robby Krieger: I saw Dylan perform I think in 1963. I was in high school in Menlo Park, near San Francisco. There were some guys there from Boston and New York in the dorm with me and they were into Bob Dylan. I had never heard him before. They had his debut LP. So they played the first album and I got totally into him.

On Dylan’s first album I really liked his guitar playing. I thought he was a great fuckin’ acoustic player. He did some stuff that was pretty damn good. And his harmonica work. I had never heard anyone play harmonica like that. Not a blues harmonica player sucking in the notes. I was amazed he could do all that stuff and sing at the same time.

Then, what do you know. He came to Berkeley for the first time and we saw him at the Community Theater. We just got tickets. I wasn’t hooked up then. (laughs). It was a good experience. He had the buckskin jacket. I bought into the whole thing, basically. I later bought a harmonica rack holder. When I saw him live I sort of realized at the time there were some interesting and unique tunings on stage. I thought he was pretty cool at that first concert. And then the week after that we saw Joan Baez play at Stanford University.

I loved his Bringing It All Back Home LP. That was my favorite. It all made sense. The lyrics fit exactly what I was thinking when I was acid. It registered, you know. ‘Wow. I’m listening to this guy.’

My favorite song was “Mr. Tambourine Man.” I might have been in my band then called the Psychedelic Rangers. I had been playing guitar for a couple of years and started at age 15. At the Long Beach concert at first I didn’t know what to think. Because I was expecting it to be how it was before. But then I realized this

I didn’t really get into Dylan until I saw him the next time in Long Beach in 1964, or ’65. An auditorium. That’s when he first came out with the electric set. Not only that, but I was on my first acid trip. It actually was not even acid but Morning Glory seeds. I think I schlepped down from Menlo Park.

I went by myself. I had two tickets, and I had taken these seeds with my girlfriend and she didn’t want to go. So I went by myself and my mind was blown. I expected him to be the same as he was earlier in Berkeley and here he comes out with an electric band and wearing a Hollywood Zoot suit. I didn’t know what to think. In Long Beach he was totally different. And that was one thing about Dylan that was always great. He always changed.

I loved Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited album. I loved Michael Bloomfield’s guitar playing on that album and loved Bloomfield on the first Paul Butterfield Blues Band album.

I never saw Bob Dylan again except when the Doors were being inducted into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame when the ceremony was held locally in Los Angeles at the Century Plaza Hotel. We then walked backstage to get ready to go on and there was Dylan. We all hung out for a few minutes. I would love to play with him sometime.

Al Kooper No one talks about Bob’s piano playing because they don’t know. Bob had a very unusual way of playing in that he didn’t use his pinkies. So both his pinkies were up in the air when he played the piano and that’s very interesting to me. It was very interesting looking to watch that. I used to really get a kick out of that.”

I played organ on “Like a Rolling Stone.” (Pianist) Paul Griffin was a big influence on me as well. Paul came from the Baptist church. On Highway 61 Revisited we did the tracks to “Tombstone Blues” and “Queen Jane Approximately” in one day.

The best thing I can say about Paul Griffin is take five minutes out of your busy day and get a time where you have nothing to bother you at all. Find a real nice stereo system and sit back and put on “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” ” from Blonde on Blonde. And just listen to the piano…And tell me if you can find on a rock ‘n’ roll record anybody playing better than that. And I would really like to hear what your decision is. To me it is the greatest piano achievement in the history of rock ‘n’ roll.

I don’t hear anything than him playing the piano when I hear that record. And I’m thrilled that I’m playing organ but I’m embarrassed. And I think that Dylan should be embarrassed to. ‘Cause he just steals that fuckin’ record. It’s the most incredible piano playing I’ve heard in my life. If you’re a piano player try playing that note for note. It’s just incredible. Griffin also played on those Chuck Jackson records like “Any Day Now.”

There’s a few reasons why Blonde on Blonde holds up so well. The main reason is the chemistry of the participants. That’s the main reason. And the other reason would be the songwriting. I think the combination of those two things could make if they were as wonderful as those two were on that record it could make any record last a long time. The credit has to go to (producer) Bob Johnston. It was his idea. He had tried to get Dylan to record in Nashville in late 1965. He knew about the chemistry. And I also think he felt more comfortable there because he lived there. And he knew all the musicians intimately.

I’ve cut probably three other Smokey Robinson tunes over my career. He’s special. One of my favorite things is when I called (Bob) Dylan one day and said, “Hey…What are you doing?” “Eating a piece of toast and listening to Smokey Robinson.”

Murray Lerner My Newport 1963-1965 film footage over the years with Dylan depends on music in a way that Leonard Cohen doesn’t, I think. It stands on its own more than Dylan does, I think. Dylan is brilliant. I trust in a sense whatever he says. He actually likes to tour and he likes the involvement with the crowd. You never know what he really thinks. He loves teasing people. All performers have a common thread of some kind or they wouldn’t perform. And Leonard Cohen on stage and in film is different than Dylan.

Dylan, Newport ’65, I think there was more than just the electric. You have the peer pressure if someone boos, it’s nice and campy to boo. I think that had an effect on it. ‘Cause there were a lot of people who weren’t booing. And I was there. But I didn’t really hear the audience I was so intense on the photography.

But it’s interesting, when I’ve had screenings of it, like at the New York Film Festival, always lots of applause. And later there is a question and answer session. I always get up and say, “I’m really disappointed I had hoped you would have booed me.” That gets a good laugh. But then, there was a thing at the New York Film Festival. Three people got up. Each said I was there. One said the booing only came from behind the stage. Another person said, “I was there and the booing came from the press pit and the first few rows.” And then the third person said something totally different. There were three different variations from people who were there with witnesses. And it was quite a moment. It’s hard to know.

The other part to me which is fascinating is the message of those songs. “Maggie’s Farm” and “Like a Rolling Stone,” is very much in tune with what the kids really felt. They expressed their feelings. But they didn’t understand that. They were reacting to something else. “Maggie’s Farm” was about work and drudgery. “Rolling Stone” the feeling of alienation was very common in those days.

Paul Body: Every now and then the whole earth shifts on something. In ’65, it was when “LIKE A ROLLING STONE” hit the AM airwaves. Zephyr like it took over the airwaves. It was something that you really hadn’t heard before. Of course, if you took the thing apart, you would hear that groove came from a bunch of songs like “My Girl Sloopy,” “Twist and Shout” and “La Bamba.” There was a Latino feel about it. You put that with words and it was wild ride into the devil’s punchbowl. It was sheer perfection. It sounded like the Sunset Strip with the tambourines in the background. Yeah, the world shifted. BOB DYLAN was the new king. Brillo pad hair, Spanish boots, so thin that almost disappeared when he turned sideways. He was a kid then, now he’s reaching 80. Bob Dylan 80???????. Glad that I was on the planet that Summer and I was glad that Al Kooper didn’t listen when Tom Wilson said…"Al, you don’t play no organ.” Damn, that song was perfection. Still giving me goose bumps. How does it FEEL? It feels like………..”

Jan Henderson: Unbeknownst to my ears, I had heard Bob Dylan’s work before knowing who he was. In the mid-60s my neighbor in Laurel Canyon Dennis Hopper, played me Highway 61 Revisited. To say the least, it was an eye-opener, somewhere between rock and folk. A stellar piece of work.

Jerry Schatzberg: I think any photographer that photographs another person tries to capture that person as best he can. By this time I knew Dylan quite well. I’d been photographing him for about a year. We’d hang out together and go places. When you’re in that kind of a relationship you are getting into somebody’s soul.

The first set of photographs I took of him was in 1965 in the recording studio with a Nikon. I had asked Al Aronowitz who was in my studio who was talking to a disc jockey that I knew and I was probably photographing somebody. My ear heard them say, “Dylan, I saw him yesterday. I’m quite friendly with him.” I said, “Hey, the next time you see him tell him I’d like to photograph him.” The next day I got a call from his wife Sara. Who I knew before she even knew him. She was the one who kept telling me about Bob Dylan. Sara said to Bobby that I would like to photograph you’ and he said OK. And I replied, “I’d love too.” She gave me the address where they were recording Highway 61 Revisited. Next day I went over and was welcomed. He even let me hear some of the sides they were doing and comment on it. I must say I was a little intimidated at first but they really made me quite at home.

The first shoot was during the Highway 61 Revisited recording studio and, of course, that’s his kingdom. He could do anything he wants because he’s comfortable there. He was also comfortable around me because of Sara and Al. I got the photographs in and wanted them to like them and they did. And that’s when I wanted to get him into my studio where I had more control. And once he came to my studio, there was nothing he’d say no to, basically. I’d find a prop that I might have used in a previous photograph, I’d give it to him and he’d do something with it. He was just very cooperative and he felt at home too.

But, you know, when you come across a talent like Dylan…I didn’t catch on to him at the beginning. I was listening to him and it was Sara and Nico from the Velvet Underground they kept yelling, “Genius.” I was very impressed what I heard and what he was doing. He was funny.

Everybody over the years was trying to figure out what kind of drug trip we were trying to portray since the cover of Blonde on Blonde was out of focus. Nothing to do with that. It was January. Dylan had on a light jacket and I just had on a light jacket and a number of the images while we were moving around were moving, you know. So they were blurred a little bit. I must say Dylan chose that one and I was delighted. I knew there are a number of other good images from that shoot that were quite good which I use now. But people thought we were trying to say something more than what we were.

We used to go to my club, Ondine’s. I was a stock holder, sit at the bar and hang out. At Ondine’s we put on west coast bands like the Doors and Buffalo Springfield. I loved the Doors on stage. Jim Morrison off stage was quite different than Dylan. Bob, although he was quite into himself when he was on stage, when he was off stage he had fun with his friends. He was open. Jim Morrison was really introverted. The rest of the band was quite open. It wasn’t that he didn’t talk to us. Maybe he was shy

Re-visiting Dylan for my book Thin Wild Mercury: Touching Dylan’s Edge was quite good. I photographed Bob’s first son with Sara. I photographed a lot of things that were very personal. I think what struck me most was when I put the book together I put all my Dylan stuff at the beginning and the interview what I did at the end. I went into my childhood, getting into photography. It worked beautifully.

D.A. Pennebaker. Originally when I made the film Dont Look Back I wanted to be sure it wasn’t about music that it was about Dylan. What you see now that maybe it should have been more about music. But in a way, Dylan was what everybody wanted to know about. And the music they could get on the records.

You had to see the music performed. The film took possession of me. I was in the zone for Dont Look Back. Maybe Dylan was in the zone. I knew that once I got started I just had to roll and not plan anything. I didn’t try and be smart about anything. I never asked him a question. I didn’t want to know anything. The whole thing was a walking tour, like walking up a mountain. Your feet take you there and when you get off the train you made sure you had a new roll of film there.”

When I did Dont Look Back I was sure I knew what I was doing. I edited it in 2 or 3 weeks. It was like walking across the Peruvian Andes on a rope and I had to move fast and not take time to think about it. With a viewer. No Avids then. You move faster and it’s closer to what the Avid will do. It’s much faster than a Steenbeck [flatbed editing system].

There was no myth or legend yet. It was so incredible. Dylan had such an amazing kind of mercurial sense that translated to people. It kind of makes you feel like you did something right once. (Laughs) It doesn’t make me feel bad at all. It interests me that people have the same fascination with Dylan that a lot of people had without being able to quite understand it. I know how I feel about Byron. I think he’s an important person in our culture and why everything is derived from what Byron set forth. Dylan, I think in a hundred years, will have some kind of same quality that people will look back and say, ‘oh that’s where that came from.’ So it interests me now that people see it in the movie that when it was made it was all a guess.

I caught that in the audience. I think that it will take 50 or 100 years to really digest Dylan. He’s like John Brown. He’s out there singing a song and he’s gonna sing it until he drops. And it’s like he doesn’t have to understand it completely. That’s what he’s going to do. The concerts now are like transfigurations but they’re interesting because you can’t sit on a talent like that whatever you do is going to be interesting.

Marianne Faithfull: I had never seen a person like Bob Dylan Never in my wildest dreams could have imagined anyone like Bob in 1965. His brain, but I was frightened. I didn’t know they were probably more scared of me. I don’t know. They were all on methedrine. He played me the album Bringing It All Back Home himself on his own. It was just amazing. And I worshipped him anyway. That was where I got very close to Allen (Ginsberg) ‘cause Allen was the only sort of person I could recognize as being somewhat like me. I spent some time with Allen and Bob during Dont Look Back.

Allen Ginsberg: I don't think I would have been singing if it wasn't for younger Dylan. Ginsberg. I mean he turned me on to actually singing. I remember the moment it was. It was a concert with Happy Traum that I went to and saw in Greenwich Village. I suddenly started to write my own lyrics, instead of Blake. Dylan's words were so beautiful. The first time I heard them, I wept. I had come back from India, and Charlie Plymell, a poet I liked a lot in Bolinas, at a welcome home party played me Dylan singing “Masters of War” from The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, and I actually burst into tears. It was a sense that the torch had been passed to another generation. And somebody had the self-empowerment of saying, 'But I'll know my song well before I start singin’.” So then in the 1970s, I began turning to Dylan. I knew him in the '60s. He taught me the three-chord blues pattern. So he was my instructor.

The renewed interest in the beat generation stems from the fact that we were being more candid and truthful than most other public figures or writers at the time. We were switched over to writing a spoken idiomatic vernacular, actual American English, which turned on many generations later. Dylan said that Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues had inspired him to be a poet. That was his poetic inspiration. So, I think what happened is that we followed an older tradition, a lineage, of the modernists of the turn of the century and continued their work into idiomatic talk and musical cadences and returned poetry back to its original sources and actual communication between people. We were built for it.

I visited John Hammond, Sr. in the hospital, on his deathbed, years ago, and our final conversation was about Robert Johnson and Bob Dylan. Wouldn’t it be interesting if you went to a concert by Dylan and he dated each piece…

Robbie Robertson: Who would think in their wildest imagination that Tin Pan Alley was a real place and the Brill Building and Donnie Kirshner’s thing. All of it was actually in a place you could go. And the doors were golden when you walked in. And inside there in all these rooms were people who wrote songs and sent them out to the whole wide world. Then, the other door was Bob Dylan who it wasn’t about that. It was about emotion, and energy, but it was really about saying something. It wasn’t about “these words could be anything.” No. No. It was specific. So to me it was rebelling in a beautiful way against this other thing.

There was a thing that happened between Bob and The Band on stage that when we played together that we would just go into a certain gear automatically. It was like instinctual, like you smelled something in the air, you know, and it made you hungry. (Laughs). It was that instinctual. And the way we played music together was very much that way. And whether, we were playing in 1966, or 1976, or when we did the tour together in 1974, we would go to a certain place where we just pulled the trigger. It was like “just burn down the doors ‘cause we’re coming through.” And it was a whole other place that we played when we weren’t playing with him. So it was like putting a flame and oil together, or something.

Bob Johnston: In 1965 I was working with Dylan in New York and standing by the sound board and I said to Dylan “Listen man, you ought to come to Nashville sometime. I got a fix up down there with no clocks and the musicians are fuckin' great.” He'd never answer you, just go “hmmm” like Jack Benny... So I finished Highway 61 Revisited and then Dylan called me about six months later and he said, “Man, I got a bunch of songs. What do you think about going to Nashville?” “That's what I was talkin' about!”

In 1966 we went down there for Blonde on Blonde and the first thing was beautiful. He said, “Well, I got an idea...” He stayed out in the studio 10 or 12 hours. He never left it. He'd eat candy bars and drink milk shakes and all, and nobody does that much. I sent the musicians away and told them to do anything you want to and be in phone contact. Don't go home... you can be in the studio down here if you need some beds or something. About 2:00 in the morning Dylan came out of the studio and said, “I got a song I think. Is anybody left here?” First thing we did was “Sad Eyed Lady Of the Lowlands.” And that was the first thing that we did for Blonde On Blonde. And from then on it just went up and up and couldn't go up any higher and higher. I think that's one of the best tracks ever cut, along with “Desolation Row.”

Dylan and I were notorious for using first takes. He liked to get it out of his head. I don't see any sense in doing it over and over. They knew what I wanted them to play not what I gave them. That's why they were there. When I started with Dylan he said, “my voice is too loud.” Good enough. So I turned it down. Then I'd turn it up. “Man, I can't hear myself” and had that voice out there. Finally, we got to the place where he said “I can't hear myself.” ‘cause I'd brought it so low. So I told him I'd take care of it and never asked him about it anymore and turned everything up and had that voice out there.

Dylan played me some songs at a Ramada Inn in Nashville, Tennessee before working on John Wesley Harding. I would place glass around Dylan for recording. He had a different vocal sound. I didn't make his different vocal sound. He always had different sounds on. I never wanted to be (Phil) Spector... and while the rest of the world was doing an album as big as Blonde On Blonde, which everybody was – the more musicians they could get, the better it was. (But) we went in with four people...in the middle of a psychedelic world!

I always had 4 or 8 speakers all over the room and I had 'em going. The louder I played it the better it sounded to me. This is the way I really did it. As a songwriter, I wrote songs, too, (but) Dylan changed the world. Every song he did I loved. I was a Dylan freak and I knew he was changing the world. I knew he was changing the society as we knew it. And I knew Paul (Simon) was too.

Charlie Daniels: When Bob Johnston moved to Nashville in 1966 he called me and said, “Why don‘t you come to Nashville?” And I always wanted to live there and packed up in 1967. He had just done Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde. All the good things that happened to me in the early days were because he was a cog in the wheel.

In ‘67 and ’68 Bob produced the albums John Wesley Harding and Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison. Bob had gained credibility. He was also at the same time, bringing Dylan and Leonard Cohen into town who had never lived here.

The first thing Bob did when he came to town was to do a number one song with Marty Robbins. And in ‘68 produced the albums John Wesley Harding, Flatt & Scrugg’s The Story of Bonnie and Clyde, and of course, Johnny Cash’s live album at Folsom Prison.

He had gained credibility. He was also at the same time, bringing Al Kooper, Dylan and Leonard Cohen into town who had never lived here. Dylan recorded in Nashville in 1966 for a while, but it was he’d come to town, do his stuff, and leave. Dylan happened to record in a studio in Nashville and worked in it.

With people like Cohen and Dylan…Most of the Nashville sessions, the country artists they would bring a demo in, they’d play the demo, you play it like the demo, you may change a key on it, but basically it’s gonna be the same thing, how they want the demo. So you’re playin’ pretty much inbounds.

With Dylan, Charlie McCoy was the band leader. “And how much do you want him to play? How many bars? How much do you want him to do?” And Dylan replied, “All he can.” Well that really describes what this is all about.

Cohen and Dylan were singers and songwriters. They write their songs, they weren’t coming in from a music publishing company. It was a lot different because there is no hurry. We went into the studio. Like with Nashville Skyline we had about fifteen sessions booked to do it and probably only used half of them and it was over. Everybody got so in to what they were doing. If you listen to Dylan, the stuff before and after, Nashville Skyline stands out. It’s a different kind of record. The material was a little different and dealt with different themes.

Nashville Skyline and John Wesley Harding are two different records to me. The Nashville Skyline record was a departure for Dylan. It was just so different than anything I had heard him do. “What else you got Bob? We got this one done.” And of course, Dylan is a big first take guy, if you can get it on the first take that’s how he wants it. And I like that about him. I’m the same way.

Clive Davis: In June 1967 I really came to the Monterey International Pop Festival not knowing what to expect, but seeing a revolution before my eyes. I was very aware that contemporary music was changing. I was in the business side of it for a year. I was working with Andy Williams, the young Barbra Streisand and the young Bob Dylan. I was observing. I was seeing the business change. I was seeing music change.

Peter Lewis: There was a new frontier at the Monterey International Pop Festival and a tremendous hope. I was in Moby Grape. It’s like some of the music you heard was the sense that the people who made it to that stage kind of knew something. Whatever they knew was like part of their music, whether they were expressing everything, literally or not. Only Bob Dylan was really doing that.

Chris Hillman: At Monterey the Byrds did Bob Dylan’s “Chimes of Freedom.” I didn’t realize how beautiful that lyric was until years later. And (manager) Jim Dickson instilled in us the concept of depth and substance. He said “Do you think you’re gonna be able to listen to this 40 years later?” He brought “Mr. Tambourine Man” to us. “Chimes of Freedom” we did on that first album we all knew it. “Chimes of Freedom” is a killer. It’s just one of Dylan’s beautiful songs. And he was just peaking then.

Harry E. Northup: Every morning I would sit in my rockin' chair and read The New York Times. I saw a paragraph advertising the Woody Guthrie benefit with Bob Dylan and others. Immediately I got dressed, took the bus down Central Park West, and got two tickets for myself and my (then) wife Rita Solomon at Carnegie Hall. 4th row. She was a nice Jewish girl from Brooklyn that I met through Harvey Keitel. He came to a party I had. Bette Midler performed 'A Hard Rain Is Gonna Fall' at my party. Late 1967 or early '68.

On January 20, 1968 two Woody Guthrie benefit concerts were held at Carnegie Hall in New York. Dylan, Jack Elliot, Richie Havens, Odetta, Pete Seeger, Tom Paxton and Arlo Guthrie shared the bill. Actors Will Geer and Robert Ryan served as narrators. The thing I remember most about the show was that each folk performer would do a tune, like Judy Collins would be on stage right, she would sing, and Pete Seeger would be on the opposite side of the stage and he would sing. And they would alternate. In the back of the stage I saw these old guys who all had beards, sitting. “Who are they?” Toward the end of the first half of the show all of a sudden Bob Dylan came on and these guys got up and played with him. Instead of doing one tune in a folk way, Dylan did like 12 or 13 minutes of Woody Guthrie material and really socked it to you.

It was like a rock concert. It was rockabilly with Dylan's voice on top of it. I remember Dylan looked at me and I looked at him and I felt he was looking right at me. It was one of the two best concerts I ever went to. I went to the Elvis Presley show in 1960 at the Pearl Harbor Auditorium in Hawaii. I was in the Navy. I was sitting in the balcony. And remember looking at a guy walking around with an attaché case and it was Col. Parker. Elvis would make a little move with his finger and the whole crowd would go nuts. He was the king.

Bob Dylan was just beautiful and electrifying when he came on. He transcended the folk genre, lifted it up and really hit me square between the eyes with a force of nature. I didn't know who the hell the people behind him were. Dylan on stage was so beautiful it was like Elizabeth Taylor. Dylan hit the audience with that force of power like a rock performer.

Steven Van Zandt On my Outlaw Country channel [SiriusXM] I program a lot of Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. I've programmed Rod Stewart and the Faces covering 'The Wicked Messenger' from John Wesley Harding and Jimi Hendrix doing “All Along The Watchtower” from the same album.

Jimi Hendrix did more to promote John Wesley Harding than anybody. It was one of the most remarkable records ever made of course. And the fact that Jimi picked up on that from that unusual, and not very popular Bob Dylan album and made everybody go back to it. And, I'm telling you, that's how powerful that record was. Everybody went back to John Wesley Harding after hearing Hendrix thinking, 'you know, maybe I missed something? Look what Jimi Hendrix did with it. Look what the Faces did with it. It worked. It's a terrific album but sort of subtle, compared to Blonde On Blonde that most people consider Bob's peak. Blonde On Blonde which I think is the greatest record anyone ever heard.

Then it got a little bit more electric on Bringing It All Back Home, and then when I heard “Like A Rolling Stone” as a kid was the first time he meant something to me all of a sudden Wow! This was something different, new and interesting.

As a guitar player, I've played his songs with Bruce [Springsteen] and in top 40 bands earlier. He was an extremely good folk guitarist as far as the folk style he played on his first few albums extremely adept at that. Then he went electric and started having some fun. His first solo might have been the intro on “Leopard Skin Pill Box Hat.” It's a funny solo and expresses that part of him. And when he wasn't playing the guitar himself, he brought in Michael Bloomfield for Highway 61 Revisited and Robbie Robertson for Blonde on Blonde.

Athough the Byrds introducing him to the world, really, with “Mr. Tambourine Man” was a major factor. I can't give them enough credit for that. I don't know if Bob Dylan would have been accepted at Top 40 radio if it hadn't been for “Mr. Tambourine Man.” I mean that, Harvey. That gang has been a great service to the world. I was a huge Byrds' freak. Still am. As you know they lead you to Bob.

Jim Dickson: I was working with the Byrds. I knew Jack Mass, the local representative of Witmark Music, who at the time published Dylan’s copyrights. Mass along with publisher Artie Mogull was instrumental in getting me the acetate of Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

The lyrics blew my mind in Bob Dylan’s songs. Victor Maymudes, who was Dylan’s road manager for a while, earlier was doing folk music. I had known him for quite a while. Victor arrived with the first copy of a Dylan album to the West Coast. And he played it for me and I wasn’t that impressed.

But when Dylan came to the Monterey Folk Festival, 1963 or ’64, I went over to a room with Victor and some other people and Dylan had a whole bunch of new songs and he sat there and played them all. Him and the guitar. And that’s what blew my mind. He had one great song after another. He was playing them live.

It was the first time I met Dylan. The songs became alive in front of me and they were all new songs that weren’t on his first album. He sang about 20 songs and I was just glued to them. I never heard anybody write like that. He was just playing one song right after another. And they were amazing. When I heard “Mr. Tambourine Man” I said, “that’s the best. That could be a hit song.” Artie Mogull just gave me the song. And I put my head down and went after that one with the Byrds

Dylan came to the Dick Bock World Pacific recording studio on 8715 W. 3rd Street in Los Angeles more than once. One time with Bob Neuwirth, who played a key role. Dylan also sat there and played the piano with them, got to know them a little bit. Michael Clarke was still playing on cardboard boxes with a tambourine on top. He didn’t have his drums. McGuinn took it over and had a 12 string acoustic guitar with a pick up and Dylan walked around listening to what each person was playing. They were right and he thought they were really charming.

Then I sent the record to Dylan, we had to get his OK. That’s where Bobby Neuwirth comes in. Dylan and Neuwirth sat on the floor and they wore out the first acetate I sent ‘em. And they listened to it over and over and that’s when Neuwirth said, “you can dance to it.” And Albert was trying to talk him out of it.

Dylan and Grossman had the finished product but Neuwirth was able to persuade Dylan, “Hey man, it’s a rock ‘n’ roll band playing one of your songs.” And going up against Albert was not comfortable for him, but he OK’d it and we were able to release it.

The Byrds first heard it all together on the local Hollywood radio station KFWB when they were in a car, a station wagon they bought from Odetta. They had to pull over. At Ciros’s nightclub on Sunset Blvd. Dylan got up on stage with the Byrds and played the harmonica. And he gave me permission to use a photo I took of him and the Byrds on the back of their first LP. I wasn’t really surprised with what he came up with after that.

Roger McGuinn: Our producer Jim Dickson loved “Mr. Tambourine Man.” We didn't get it. He had to bring Bob Dylan around to the studio for us to do the song at all. Dylan came over with Bobby Neuwirth and we played “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “All I Really Want To Do”for Dylan and Bobby, and Neuwirth said, 'Wow. You can dance to it.” After “All I Really Want To Do,” Dylan responded, “what was that?” And we responded, “That was one of your songs, man.” “I didn't recognize it” he said.

After “Mr. Tambourine Man” we just loved Bob Dylan's writing. I had a real heart for his lyrics and really sang them from the heart. I remember one time he took me aside, I went over to the hotel he was staying at and said, “You know, I used to think of you as just an imitator but I heard 'Lay Down Your Weary Tune', and listened to that and you're doing something that wasn't there before. That's really good.”

He said all your life when you're a kid you're trying to get older. And then he realized he had gotten to a place where the kind of older thing wasn't desirable encumbering his freedom and liberty. We became his “unofficial, official” band for his stuff. Dylan’s “Chimes Of Freedom,” that we did at Ciro’s, and to this day it’s still in my own repertoire. I think it’s a great song. I love the poetry and imagery of it, you know, and it has some political feeling but it is ambiguous. You can read whatever you want into it.

The Byrds’ 1967 cover of 'My Back Pages” was Jim Dickson's suggestion and I hadn't thought of it as a song for the Byrds repertoire. I couldn't believe we had done it. It sounded so creamy, rich, big and full.

I also liked the wisdom of “My Back Pages.” It's a very insightful song on the thing that happens when you think you're so knowledgeable and wise when you're real young. And then when you get a little older you realize what you didn't know. Dylan's stuff is brilliant. I coined the term that he was the “Shakespeare Of Our Time.” It was like knowing Shakespeare here. Dylan was carrying on Kerouac and Ginsberg. The baton had been passed. I remember Ginsberg said “I think we're in good hands.”

David Leaf: Bob Dylan plays a significant role in all three of my UCLA courses: “Docs That Rock, Docs That Matter,” “Songwriters on Songwriting” and “The Reel Beatles.” I introduce the students to Mr. Dylan through a curated playlist, pop covers (Byrds, Turtles, etc.), “Rubber Soul,” and two documentaries (“Dont Look Back” and “No Direction Home”). They hear the music, meet the iconoclast. No preaching from me. Then, it’s up to them to go down the rabbit hole and listen and watch forever. Happy Birthday!

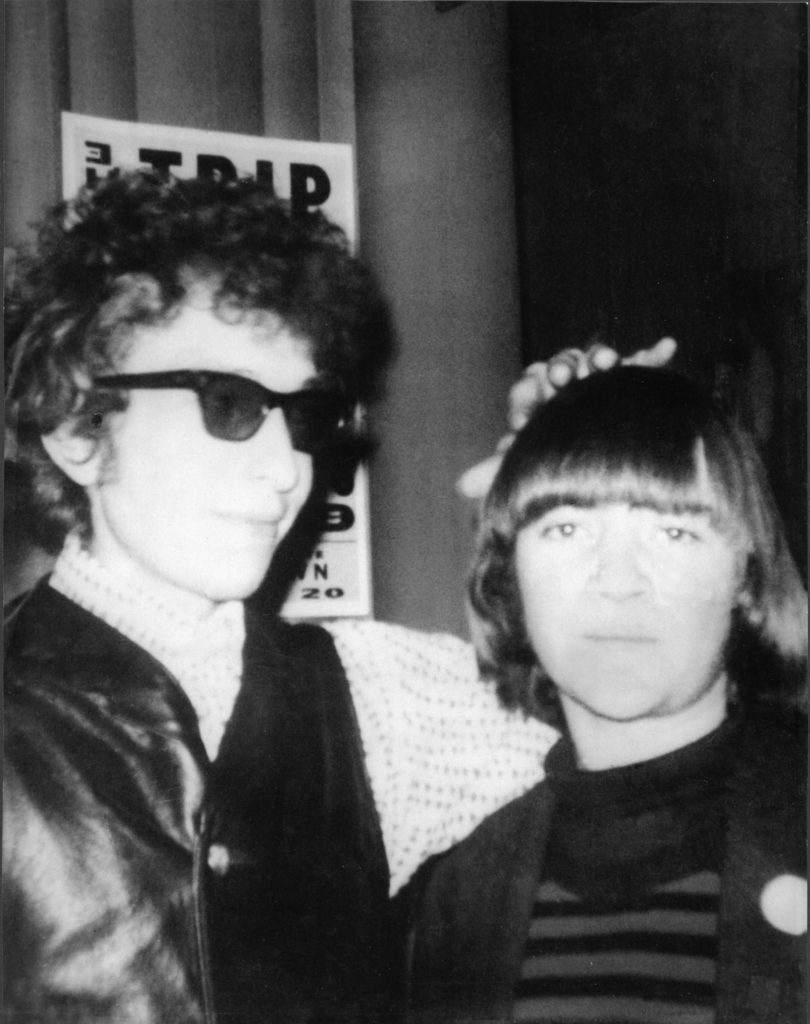

Rodney Bingenheimer: I met Bob Dylan in 1965 at The Trip nightclub on the Sunset Strip. At the club I was with Billy Hinsche of Dino, Desi and Billy, who took a photo of Bob Dylan and I holding my camera.

I went to the amazing December 1965 Dylan concert at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. Marlon Brando sat in front of me. After the show, which was on my birthday, we got up from our seats and went backstage. It was all happening! I love Cher singing his tune “All I Really Want to Do.” Many years later on an airplane Bob saw me and said hello. I was on my way to Brooke Shield’s 21st birthday party in New York.

Al Schmitt: I did the Dylan album Shadows in the Night with the Frank Sinatra repertoire. It’s the same room Sinatra used for his Capitol albums. You’re standing in the Capitol studio B where Bob Dylan and I cut it.

That was quick one. The nice thing about recording everything at one time was that you knew exactly what it was going to sound like. When you started layering things you were never sure. Then a lot of experimenting came in and it took longer and longer to make records and the expenses went up and up.

In the sixties when I was doing Jefferson Airplane we block booked time at RCA studios and we were there for five months doing After Bathing At Baxter’s.

Dr. James Cushing Bob Dylan is twelve years older than I am, and a twelve year age difference is about right to establish a mentor role, which Dylan has filled for me and so many others my age for most of my life — the trusted older guide, not a father but an older guy who had done some hard traveling, taken what he had gathered from coincidence, and could help us live an authentic life. Dylan’s authority was based in his authenticity, and we felt it instinctively. Now, having won the Nobel Prize and sold his publishing catalogue for who knows how many millions, Dylan turns 80 on May 24, 2021. My father, a stern ex-Marine who hated all things countercultural, was 80 when he died on May 25, 2001. But Dylan inhabits that age not as a patriarch but in the same way he wears his Nobel medal: ambivalently, as a perpetual outsider, a chameleon poet who contains multitudes, remains in a state of becoming, retains the spirits of Woody and Cisco and Leadbelly too. He will not be pinned down. He is the most important living American cultural figure.

Kenneth Kubernik: I'm writing this on May 8th, V E Day, and the birthday of another American original, a musician whose body of work, scope of influence, and inscrutable personality mirrors so many of Dylan's most singular attributes. Pianist Keith Jarrett is not a name that leaps to mind when talkin' 'bout Bob's imperishable impact, that litany of artists long identified with his idiosyncratic approach to song craft, interpretive wanderlust, and rousing conviction.

There is nary a one that reeks of jazz. But Jarrett - revered by players and serious students of improvisation, reviled by the jazz constabulary for his irascible nature - has, since the '60s, spun closely within Dylan's musical orbit. When jazz was moving uncomfortably towards rock and funk, Jarrett had his trio perform "My Back "Pages," and "Lay Lady Lay," coping a Floyd Cramer groove more redolent of Nashville's skyline than Manhattan's hot house revelries.

In an interview with England's Melody Maker, Jarrett cited Dylan's insight that artists "walk a razor's edge," when asked to describe the opaque process behind his mesmeric solo piano recitals. More than Monk and Miles, Trane and Bird, Jarrett found common cause with Dylan's redoubtable independence of thought and action. It is amusingly apt that Dylan, in recent years, has turned to performing the American songbook - "standards" - that provide the beating heart of every educated jazz musician. He's on Jarrett's turf here and one can only imagine that aching croak nestled inside the pianist's ineffable accompaniment. Wonder boys...

Michael Hacker: We are blessed to breathe the same air that Bob Dylan does as he enters his 81st year. In lieu of tribute, I would just point to Dylan’s most recent recording, which was released in his 80th year on the planet. Rough and Rowdy Ways stands shoulder to shoulder with the strongest of Dylan’s other works. It’s a phenomenally alive record, and as such, stands as a shining exemplar of what we can all aspire to as we age. Happy birthday, Captain.

Chrissie Hynde Bob Dylan's "Forever Young” has got such a beautiful lyric. I just love it. He's the pride of our generation. The song is genius. I'll tell you another great Dylan album, that was not one of his most popular ones, was Shot Of Love. The song, "Lenny Bruce.”

Time Out Of Mind. It’s one of his best albums. He just sings magnificently, for a start. They're just great songs. Bob always writes impeccable songs, but my suspicion is that he's a little impatient in the studio. On this one, he really stuck it out and got gorgeous vocals. The singing is fantastic. The songs are so well crafted and they just got the great sound for each song. You don't feel like he just got a band in, wheeled them in and played all the songs and left. Each song is very carefully thought out. Obviously that's a lot in the production and I'm sure that's Danny Lanois who masterminded that. Jim Keltner is the perfect drummer for any band if you ask me. He's great with Bob Dylan. Keltner is a genius drummer. I love that guy.

Curtis Hanson I’ve had a decades-long dream of working with Bob Dylan. I saw him in 1963 at the Hollywood Bowl where he played with Joan Baez. Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid is one of my favorites.

I vividly remember seeing the movie the first time right here in Westwood. I then saw it several more times. It was butchered but it was still great. And Dylan’s music was such a knockout. That score cue when Pat Garrett is walking toward that house where he will eventually shoot Billy The Kid is just beautiful. It’s a stunning piece of music, and of course, “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” and “Billy’s Theme.”

It’s funny, each movie that I’ve made when I’ve gone on location, I’ve always taken that soundtrack album with me. I’ll take a dozen things I enjoy listening to but I always include that album because to play it in my car driving toward location at certain times, is like tonic. “They don’t want you to be so free” expresses the feeling that you get when you fight and lose, and yet persevere and try to win the more important battles yet to come. It brings back Peckinpah’s struggles. I’ve always carried that with me. It’s an important part of my musical identity.

Dylan’s involvement in Wonder Boys came together this way. Carol Fenelon [music supervisor] had lunch with Jeff Rosen, Dylan’s (music) manager in New York, and talked about the possibility of using one or two of Bob’s songs in the movie.

I learned from that meeting that Bob had been a fan of L.A. Confidential. This was very early on. I was already in Pittsburgh. And then months went by, and Carol nurtured the relationship and began discussing the possibility of a new main title song. Not long after I started editing, she arranged for Bob to come by my editing room in Santa Monica.

I had never met him before. We skipped through the movie. I showed him about an hour and a half of rough cut footage and he responded immediately to the visuals of the movie, the performances, the way it felt. We talked about the themes and visual metaphors in the film. I went over bits of the plot with him so it made more sense, because there were a lot of characters to follow. He asked questions about the tempo and feel of the music I wanted.

He then went away and went on tour with Paul Simon, and he called me from the road a couple of times, and we talked a little more. Then we eventually heard he was actually putting some words down on paper.

A few weeks later I get a little FedEx package with a CD in it. Carol came over, I knew it was coming, and we closed the door and popped it into my CD player and played this song. The themes and metaphors of the film, the nuances of the character, were all there, restated with Bob Dylan’s unique imagery and poetry. And we looked at each other and played it again and again.

“Things Have Changed” is a compelling song that brilliantly captures the spirit of the movie’s central character, writer Grady Tripp. [Michael Douglas]. It’s been a long wait since Pat Garrett, but it was definitely worth it. “Things Have Changed,” “Buckets Of Rain,” “Shooting Star” from Oh Mercy! and “Not Dark Yet” were licensed for Wonder Boys.

Harvey, it’s the payoff. Unlike Grady, who was paralyzed by the success of his first novel, by the time I got some success, it liberated me. The commercial success of The Hand That Rocks The Cradle and The River Wild allowed me to make L.A. Confidential, and to make it the way I wanted to make it. And then it was the success that movie was fortunate to enjoy that gave me the leverage to do Wonder Boys the way I wanted to do it. It’s as simple as that.

Ram Dass: I came from classical and jazz. I really liked Dylan. He was close to Allen Ginsberg, and I was close to Allen. I loved Dylan’s music and took many acid trips listening to his music.

Greg Franco: Free Trade Hall, Manchester England 1966.

An audience member shouts “Judas,” as Bob Dylan picks up and plays an electric guitar. Not only did Bob say, “I don’t believe you. You're a liar,” but off microphone he said, “Play Fucking Loud.”

The drums came pounding hard, perhaps the hardest we ever heard them with Dylan. They were provided by Hawks member Mickey Jones, a real hulk of a man, a biker, and founding member of The First Edition with Kenny Rodgers.

As musicians we all know the drummer rules. If we can’t be as loud as he is, we are unheard. So hey! When Dylan said "play loud," the band launched into “Like A Rolling Stone” and created one of the legendary moments in rock and roll history.

Dylan turns 80 this month.

In 1966 he shocked the folk music world to the point where he was called Judas. How biblical, how backwards. It all makes sense. Bob Dylan’s contribution to music is that he came from folk music but defied it, although he never really completely turned his back on it. When he rebelled, the era of pristine folk music was wounded perhaps beyond repair.

Dylan was smart to kick sand in his critics’ faces. They wanted to tell him how to be an artist. He essentially said I’m not your folk music robot. He drew a middle finger, not a thumb’s up.

That spirit needed to happen, not to negate what came before it, but to be freed from its lofty expectations. It ranks among one of the most significant events in the history of popular music, rock and roll, and yes, everything that ever really mattered.

What matters anymore?

We need that again in another paradigm shift. Who will provide it? At 80, maybe we need Dylan to do it again!

Now that would be insane.

He showed us something really important about life, not only his craftsmanship, but his longevity and attitude.

Bob Dylan IS the man, he always will be. Leonard Cohen, Brian Wilson, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, John Lennon, and Bob from Hibbing, Minnesota. That’s the Mt. Olympus of Music.

Happy 80th Bob Dylan.

Gary Pig Gold has 80 GOOD REASONS TO CELEBRATE

BOB DYLAN’S BIRTHDAY THIS YEAR

- His previous 79 years.

- Most notably, between the hours of 8 and 9pm on the evening of May 17, 1966 in the Manchester Free Trade Hall.

- Chronicles: Volume One.

- Blonde on Blonde …in MONO, of course.

- Not to mention Columbia single # 4-43683.

- “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” …Before the Flood version especially.

- He recorded no less than Elvis’ “That’s Alright, Mama” at his very first “electric” session.

- He recorded his first – and so far only – # 1 song at the age of 78.

- He totally gets Smokey Robinson.

- He wrote the best-ever Picnic song.

- Introduced the Fab Four to jazz cigarettes (…Is it any wonder then that he later…)

- Portrayed the coolest-ever Wilbury.

- His Theme Time Radio Hour.

- The band he used when he performed at Newport in 1965.

- The wig he used when he performed at Newport in 2002.

- “I’m looking for a place that will collect, clip, bath and return my dog. I want a dog that’s gonna collect and clean my bath, return my cigarette, and give tobacco to my animals, and give my birds a commission. I’m looking for somebody to sell my dog, collect my clip, buy my animal and straighten out my bird. I’m looking for a place to bathe my bird, buy my dog, collect my clip, sell me cigarettes and commission my bath. I’m looking for a place that’s gonna collect my commission, sell my dog, burn my bird, and sell me to the cigarette. Gonna bird my buy, collect my will, and bathe my commission. I’m looking for a place that’s going to animal my soul, knit my return, bathe my foot and collect my dog. Commission me to sell my animal to the bird to clip and buy my bath and return me back to the cigarettes.”

- In fact, the entire Eat the Document film.

- His performance at the 1991 Grammys.

- His Lifetime Achievement Award acceptance speech at the 1991 Grammys!

- His 1963 Tom Paine Award acceptance speech …possibly.

- “If Dogs Run Free.”

- “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” …listen to the melody, too.

- Invited Brian Jones over during the Great Northeastern Blackout of 1965.

- Asked Frank Zappa (!) to produce Infidels.

- His canned goods inventory scene in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.

- His Live Aid, um, performance.

- His $4 million, twelve-acre, ranch(es)-style six bedroom, seven bathroom, recording-studio-equipped onion-shaped copper-domed Point Dume “Malibu Taj Mahal” complete with 20-foot whale-tiled fireplace and vintage full-sized automobile suspended from the living room ceiling.

- Has more unauthorized bootleg recordings out there than the Beach Boys have Greatest Hits albums.

- That rap number he recorded with Brian Wilson.

- That limo ride he took – and filmed – with John Lennon in ’66 (see # 17).

- Always carries a large light bulb.

- Always remembers to remember Buddy Holly.

- Masked and Anonymous.

- “I’ll let you be in my dreams if I can be in yours,” he said that.

- His harmonica playing.

- His lead guitar playing …on the first 12 bars of “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” especially.

- Jimi Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower.”

- Suze’s “Cough Song.”

- Race Marbles’ “Like a Dribbling Fram” even!

- He walked out on Ed Sullivan (unlike Jim Morrison and Mick Jagger).

- But, he had breakfast with then-governor Jimmy Carter in 1974.

- He recorded the definitive version of “The Boxer.”

- He recorded the definitive version of “Froggie Went a-Courtin’.”

- He even recorded the definitive “Yesterday” …with George Harrison on guitar!

- His masterful telephone etiquette with A. J. Weberman.

- His Victoria’s Secret commercial.

- Those long, pretty damn dirty fingernails on the cover of Nashville Skyline.

- That long, damn funny promotional video for The Original Mono Recordings box set.

- His long-time friendship, and mutual admiration society, with Johnny Cash (also see # 17) (again).

- His Chopped Liver band.

- His “Must Be Santa” video!

- “Lenny Bruce.”

- Elston Gunn(n).

- Renaldo and Clara …yes, all FOUR hours of it.

- He hung out – a LOT – in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada (with Grizzly the Wrestler) during the making of Hearts of Fire.

- He not only hung out, but motorpsycho’d around New Orleans with Eric Burdon during the making of Oh Mercy.

- Tarantula (especially page 10).

- Wrote “Lay Lady Lay” for the Everly Brothers and/or Midnight Cowboy.

- Recorded “Buckets of Rain” with Bette Midler.

- Auditioned Dharma Montgomery for his band.

- …Revisited.

- Got the non-evil eye from Gorgeous George.

- Got Milton Glaser to paint his idol’s name into the hair on his Greatest Hits album poster (see # 7).

- He (inadvertently) wrote the theme song for “Absolutely Fabulous.”

- He showed up on “Pawn Stars”

- …to autograph his Self Portrait, no less !!

- Performed for the Pope.

- “Judas!”

- Soy Bomb !!

- Granted an interview to the American Association of Retired Persons magazine to promote his Sinatra album.

- Was once almost – almost – the new King of Comedy on HBO via Larry Charles.

- Rode in a Chrysler 200 (and an old elevator) in a Super Bowl commercial.

- Talked back to Watson in an IBM commercial.

- Managed to once rhyme “Delacroix” with “employed.”

- Managed to mix Allen Ginsberg with Bill Haley’s Comets on The Basement Tapes.

- Put John F. Kennedy, among many others, at the top of the Billboard charts in 2020 with “Murder Most Foul.”

- Shortly thereafter, Bob sold his entire song catalog of over 600 titles to the Universal Music Publishing Group.

- …and it only earned him $400,000,000.00

- Remember, ’way back in 1967, the man realized “I’m Your Teenage Prayer” (also on those Basement Tapes), but…

- He’s younger than that now.

Other Dylan-themed 80th birthday events for 2021-2022 include The Year of Dylan, year-long northern Minnesota-county based tributes to the Duluth Minnesota born and Hibbing raised artist. On May 22nd there will be a groundbreaking of a Bob Dylan monument at Hibbing High School, as well as music at Dylan’s boyhood home in Hibbing. These Dylan-esque activities come after the Duluth Dylan Fest and the Hibbing Dylan Project.

Chrissie Hynde’s new album of original Bob Dylan covers, Standing in the Doorway: Chrissie Hynde Sings Bob Dylan will be available via BMG at all streaming services on May 21, 2021. A CD and vinyl release ships to retail on Aug. 20th. Standing in the Doorway: Chrissie Hynde Sings Bob Dylan includes new interpretations of such Dylan songs as “You’re a Big Girl Now,” “Love Minus Zero / No Limit,” “Don’t Fall Apart on Me Tonight,” and “Every Grain of Sand,” recorded last year during lockdown by Hynde and her Pretenders bandmate, James Walbourne.

The largest collection of Bob Dylan's artwork ever seen will go on display later this year in the US. Retrospectrum spans six decades of Dylan's art, exhibiting more than 120 of Dylan’s paintings, drawings and sculptures. It debuts in Miami, Florida at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum on November 30, 2021. Retrospectrum will run through April 17, 2022. The Retrospectrum exhibition premiered in Shanghai, China, during 2019. This curated version will include new, never-before-seen pieces and additional artworks from a brand-new series called American Pastoral.

The Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma is scheduled to open on May 10, 2022, with more than 100,000 items from the Bob Dylan Archive. Artifacts include handwritten lyric manuscripts to several of Dylan’s songs, previously unreleased recordings, never-before-seen film performances, rare and unseen photographs, visual art and other pieces spanning his career. The Bob Dylan Center is located in Tulsa’s arts district near the city’s Woody Guthrie Center. The venue is being designed by the architectural and exhibit design firm Olson Kundig, led by design principal Alan Maskin. A Bob Dylan Center news announcement described the BDC: “will feature cutting-edge and immersive technology in a multimedia environment that is designed to be as impressive and revealing to visitors new to Dylan’s work as it will be to long-time fans and aficionados.”

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For October 2021 the duo has written a multi-narrative volume on Jimi Hendrix for the publisher.

In 2015 Palazzo Editions published Harvey’s Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, and Neil Young, Heart of Gold published in 2016.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Eddie Kramer, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Christopher M. Allport, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

The Rock’s Backpages website (http://www.rocksbackpages.com), which currently archives over 18,000 contributions to the literature of rock music journalism, published its first digital-only anthology The Bob Dylan Electric Omnibus, e-book, a collection consisting of 100 individual contributions, including Kubernik’s 2007 feature on Bob Dylan's John Wesley Harding.

In 2015 the University Press of Mississippi published a Harvey Kubernik Dylan-centric interview with Oscar-winning director and photographer D.A. Pennebaker in their book series, Conversations with Filmmakers, edited by Dr. Keith Beattie.

This century Kubernik has lectured and conducted courses on the music business and music documentary films in Southern California at UCLA and USC. In 2017 Harvey appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio in their Library & Archives Author Series.

Kubernik’s writings are housed in book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and the Ramones’ End of the Century.

During 2020 Harvey Kubernik served as a Consultant on the 2-part documentary television series Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood that premiered on the EPIX/M-G-M channel on May 31, 2020 and June 7, 2020.

Harvey is working on a documentary about Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member singer/songwriter Del Shannon. Kubernik was filmed for the documentary in production about Hollywood landmark Gold Star Recording Studio. Brian Wilson, Herb Alpert, Richie Furay, Darlene Love, Mike Curb, Chris Montez, Bill Medley, Hal Blaine, Slim Jim Phantom, Shel Talmy, Don Peake, Johnny Echols, Gloria Jones, Carol Kaye, Marky Ramone, David Kessel and Steven Van Zandt have been lensed.