Robert Dwayne Womack was an accomplished musician, singer, guitarist, record producer, stage performer, and a songwriter.

He was born March 4, 1944 in Cleveland, Ohio, and died after suffering from diabetes, cancer and Alzheimer’s in Tarzana, California on June 27, 2014.

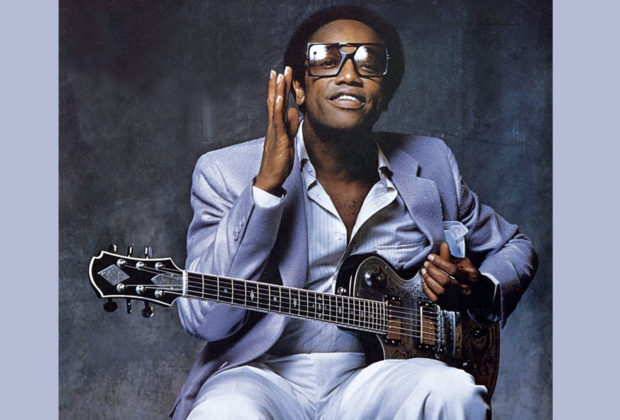

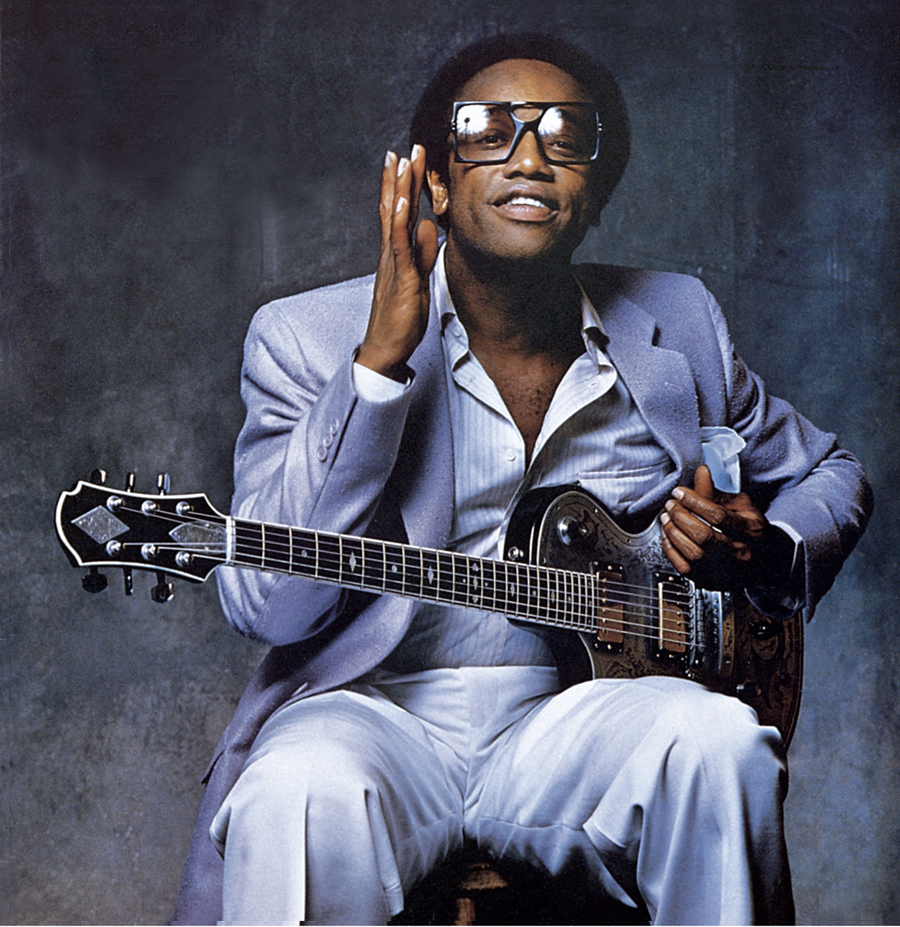

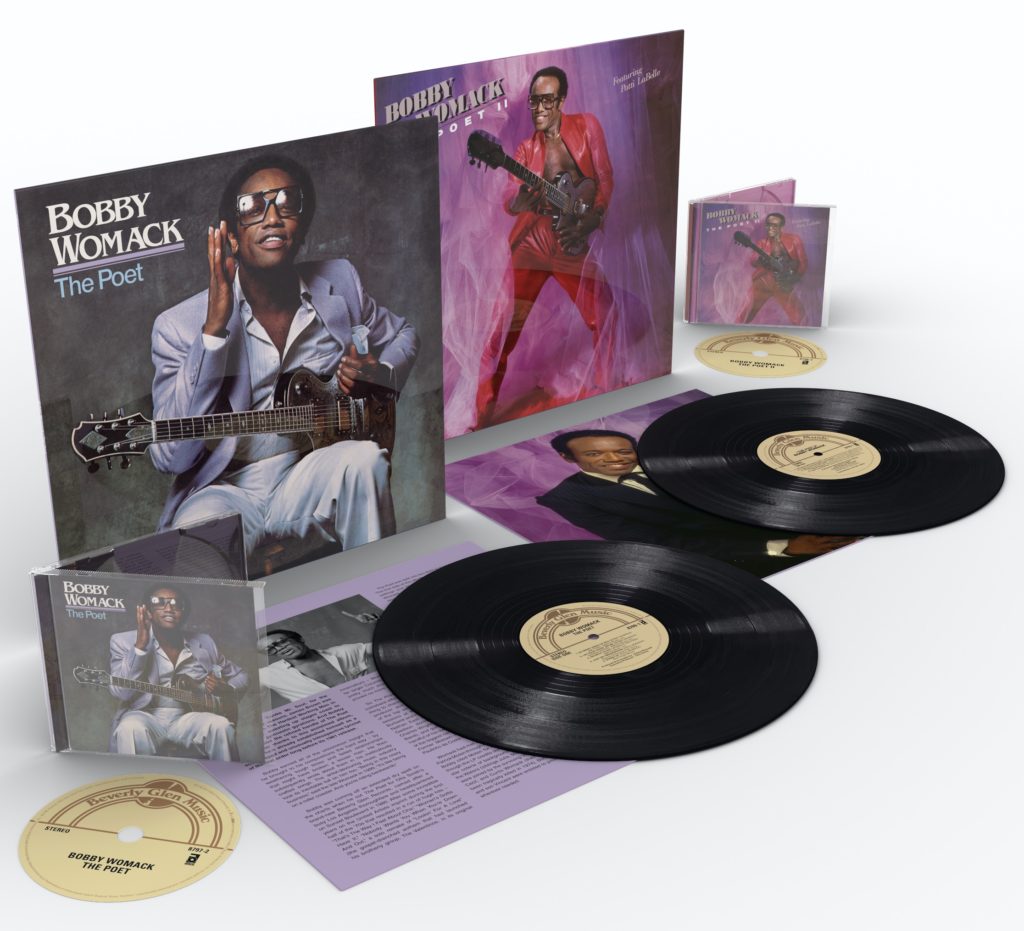

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the initial release of The Poet, the Bobby Womack album that served to relaunch his career and established him as a renewed force to be reckoned with in the urban music field in the 1980s. That album was followed by The Poet II which further solidified Womack’s position as the industry’s leading exponent of traditional soul. Now, for the first time, these influential classic albums have been remastered from the original tapes.

A February 2021 media announcement describes the Poet I and Poet II.

“Long believed to be lost, the original tapes have been recovered and are sourced for the remasters of The Poet and The Poet II. To offer the best possible listening experience, both The Poet and The Poet II will be pressed on heavyweight (180 gram) vinyl, making the albums available in the vinyl marketplace for the first time in decades.

“The historic albums packaged on LP and CD with extensive liner notes by R&B scholar Bill Dahl will be released on March 19 in the US and Canada with concurrent worldwide HD digital availability. The rest of world territories will release CD and LP on April 30th 2021.

“Shortly after its release, The Poet, produced by Womack, rose to the #1 slot on Billboard’s Top R&B Album chart and thus provided commercial validation for his musical posture that was so removed from the disco trend of the era.

"The album’s leading single, “If You Think You’re Lonely Now,” went to #3 on Billboard’s Hot Soul Singles chart and stayed there for four weeks. Decades later, a major sample of “If You Think You’re Lonely Now” provided the basis for Mariah Carey’s #1 hit “We Belong Together.” The album also yielded two additional chart singles, “Secrets” and “Where Do We Go From Here.” It went on to become the biggest selling full-length album of Bobby Womack’s career.”

The massive success of The Poet set the stage for the recording of The Poet II in 1983. As with its predecessor, The Poet II found both commercial and critical success on both sides of the Atlantic with the UK’s New Musical Express naming it Best Album of 1984.

A slew of songs on both discs were co-written by Womack and Jim Ford. His “Harry Hippie” was recorded and released by Womack in 1973.

Among the album’s highlights are three duets with Patti LaBelle including “Love Has Finally Come At Last” which was a presence on Billboard’s Hot Soul Singles chart for 17 weeks, ultimately rising to #3. Jazz guitarist George Benson is also heard on the album; his participation is something of a favor returned. Womack was the composer of “Breezin’,” the instrumental that served as Benson’s major label breakthrough.

The Crusaders’ Wilton Felder was featured on the set as was drummer James Gadson of Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band renown. He along with Andrew Loog Oldham and Womack comprised the album’s production troika.

"Bobby was wonderful,” emailed author, university lecturer and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee Andrew Loog Oldham, the producer of Poet II.

“I learnt a lot. First artist I knew of who had 3 dealers on the project, one in the vocal booth. He had a gun that didn't work to shoot Otis Smith with. Feigning alarm, I called Allen Klein, Bobby's manager (Allen would manage anyone who had known Sam Cooke) and told him about the gun and his intentions. Allen said 'does he have a license?' James Gadson was captain fantastic, the calm in the storm, master of time and delivery. Womack had lost the plot except for the occasions he could not help himself and be as sheer brilliant as he truly was. As I said, I learnt a lot."

“For me, The Poet and The Poet II stand alongside the greatest confessional art of the 20th century--the writings of Henry Miller, Lennon's Plastic Ono Band and Dylan's Blood on the Tracks, the performances of Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor at their personal peaks,” suggests writer, author and book editor, Daniel Weizmann.

“On songs like ‘So Many Sides to You,’ ‘Lay Your Lovin' on Me,’ ‘Tell Me Why,’ and ‘Secrets,’ Bobby Womack lets you right into his painful life transformation, running an inventory on his failures, his fears, and his wounds, totally without the self-pity or melodrama that a lesser artist would get snagged on. It was a funny era, the early '80s, filled with costumed techno-lust and false exuberance. Not for Mr. Womack. He stayed human, and his inner exposure was so raw, his final conclusion so vulnerable, that it's like you grow up alongside him.”

The Poet track listing

- So Many Sides of You

- Lay Your Lovin’ on Me

- Secrets

- Just My Imagination

- Stand Up

- Games

- If You Think You’re Lonely Now

- Where Do We Go From Here

The Poet II track listing

- Love Has Finally Come at Last

- It Takes A Lot of Strength to Say Goodbye

- Through The Eyes of a Child

- Surprise, Surprise

- Tryin’ To Get Over You

- Tell Me Why

- Who’s Foolin’ Who

- I Wish I Had Someone to Go Home To

- American Dream

Bobby Womack first came to prominence in the 1950s as part of the Womack Brothers, a gospel group that was comprised his siblings Cecil, Harry, Curtis and Friendly. Impressed with the group, Sam Cooke encouraged them to come to Los Angeles where he signed them to his SAR label.

They made the transition from gospel to R&B, when they recorded as the Valentinos, scoring with “Lookin’ For A Love” and “It’s All Over Now,” written by Bobby and his sister in law Shirley Womack. The song was covered by the Rolling Stones and produced by Andrew Loog Oldham becoming their first #1 hit. The song was also cut by Patti Drew in 1966 and as a duet between Womack and Bill Withers in 1975.

Womack’s legendary career included stints as the guitarist in Ray Charles’ touring band, studio work in Los Angeles and Memphis and writing for other artists. He played on sessions supporting Elvis Presley, Joe Tex, King Curtis, Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett, for whom he wrote two hits, “I’m A Midnight Mover” and “I’m In Love.” Womack was also involved in creating the landmark soul album by Sly & the Family Stone, There’s a Riot Goin’ On.

Bobby wrote “Breezin’” for jazz great Gabor Szabo, which would be George Benson’s breakthrough recording a few years later. Womack penned tunes for Janis Joplin, “Trust Me,” the J. Geils Band, “Lookin’ for a Love,” Millie Jackson “Put Something Down On It,” and Ronnie Wood, “I Got A Feeling.”

As Bobby’s solo career evolved, he became the standard bearer for contemporary soul music, with such hits as “That’s The Way I Feel About ‘Cha” and “Woman’s Gotta Have It.”

Other artists to record Bobby Womack songs include Kelly Rowland and Travis McCoy of the Gym Class Heroes, O. V. Wright “That’s The Way I Feel About You”, reggae act Dennis Alcapone, who issued a distinctive version of “Harry Hippie” entitled “Sorry Harry” and Triston Palma, who issued “Love Has Finally Come At Last” in 1984.

A new career pinnacle was achieved in the 1980s with the release of the albums The Poet and The Poet II. These evocative records by the romantic balladeer spanned numerous hits including “Where Do We Go From Here,” “Secrets,” “It Takes A Lot of Strength To Say Goodbye,” “Love Has Finally Come At Last,” “Tell Me Why” “If You Think You’re Lonely Now,” and “If You Think You’re Lonely Now”

The 1960s and 1970s were especially prolific years for Womack’s songwriting career, either as a solo writer or in partnership with the likes of Darryl Carter and Jim Ford. Jodeci’s K-Ci Hailey, a notable admirer of Womack’s work, covered “If You Think You’re Lonely Now” in 1994. On the 1994 release 1-800-NEW-FUNK, Nona Gaye did “Woman’s Gotta Have It,” produced by Prince and backed by his band, New Power Generation.

The song is sampled in Mariah Carey’s “We Belong Together”, a #1 hit in June 2005. Carey sings “I can’t sleep at night / When you are on my mind / Bobby Womack’s on the radio / Singing to me: ‘If you think you’re lonely now.'”

Hailey again covered Womack in 2006 with his rendition of “A Woman’s Gotta Have It.” During 2007, R&B singer Jaheim interpolated the song as “Lonely” on his album The Making of a Man. Neo soul singer Calvin Richardson also tapped the Womack’s songbook. “That’s the Way I Feel About Cha” was covered by the R&B musician Gerald Levert and fellow singer Mary J. Blige on Levert’s 1998 album Love & Consequences.

Womack is also heard on a 2010 album Plastic Beach by the Gorillaz as a guest vocalist on the track “Stylo.”

Bobby Womack composed and recorded music for the soundtrack of Across 110th Street in 1972 and film director Quentin Tarantino used the song in the opening and closing sequences of his 1997 film Jackie Brown. Womack’s work has been licensed in several other popular films and commercials, including Ali (2001) and American Gangster (2007). In 2005, “Across 110th Street” appeared in the hit Activision video game True Crime: New York City.

ABKCO Records and Music, Inc., is home to iconic music catalogues that include compositions and recordings by Bobby Womack, Sam Cooke, SAR Records include albums by L.C. Cooke, The Soul Stirrers, Billy Preston, Johnnie Taylor, the Valentinos and the Rolling Stones.

ABKCO, with whom Bobby Womack had an association dating back to the mid-1960s, acquired the Poet I and Poet II albums and re-released them in 2009 who are now preparing in spring 2021 these upcoming 40th anniversary editions.

Bobby Womack was a neighbor of mine for a handful of decades.

Over the last 40 years around Hollywood, at least a few times a year, I would encounter Bobby inevitably at a concert, a recording studio, a band rehearsal room, LP preview listening sessions, a restaurant, usually Thai, and in record company lobbies.

I’d also catch him at a dentist or post office, various supermarkets, sometimes at the midnight hour or even six in the morning, as well as backstage or in dressing rooms at arena and stadium venues, usually headlined by English rock royalty.

In 2009 I bumped into Bobby Womack at Marie Calendar’s bakery on Ventura Boulevard in Sherman Oaks, California. Bobby proudly stated that one of the last business transactions his music publisher Allen Klein did on his behalf in 2009 was to administer and execute the licensing request when Mariah Carey sampled his “If You Think You’re Lonely Now.”

“Now, I’ve been sampled by Mariah Carey,” he merrily told me in 2009, “and I remember telling Allen (Klein) when he was goin’ after it, ‘Man, I heard this song and it gave me life.’ He was real technical about a chorus in the song and I said, ‘Good luck.’ And that was the last major thing he did because that song was so big.”

In May of 2013, I was an on screen interview subject, along with Womack, Damon Albarn of Blur and the Gorillaz, Chuck D. of Public Enemy, Barney Hoskyns, Bill Withers, Regina Womack, actor Antonio Fargas, and the Rolling Stones’ Ronnie Wood in the BBC-TV documentary movie Bobby Womack: Across 110th Street directed by James Maycock.

When Bobby Womack died, Billboard.com on June 29, 2014 asked me to write a tribute to him (Some Kind of Wonderful: Remembering Bobby Womack).

My very first Bobby Womack sighting was in the mid-seventies at the Hollywood Boulevard law offices of Walter E. Hurst, publisher of more than two dozen reference books on music, film and entertainment law.

Hurst represented Sam Cooke, the Valentinos, J.W. Alexander, Bobby Womack, Kim Fowley, Lou Rawls, Johnny and Dorsey Burnette, Eddie Cochran, Sharon Sheely, Brenton Wood, Jack Nitzsche, David Carr and Roger Corman. Regional characters Iron Eyes Cody, Gypsy Boots, Ed Wood, Eden Ahbez and Rodney Bingenheimer were clients. Bobby kept his pit bull dog in one of Hurst’s vacant spaces.

I remember a moment in 1983 at the Chan Dara Thai restaurant in Hollywood immediately after I was unexpectedly “put on waivers” by a woman I was involved with. I medicated myself nursing Thai iced coffees and was definitely in the caffeinated bummer tent when Bobby Womack walked into the room. He had just left United Artists Records up the street on Sunset Boulevard.

Womack pulled up a chair and patiently listened to my sob story. Bobby took a long and deep breath off his lit Kool Menthol cigarette, and behind his signature tinted copter glasses explained to me some real facts of life about the fascinating erotic and neurotic aspects of women, concluding with, “Man, where do you think all my songs come from?

“Love is the principal topic I write about because it’s the most important thing in the world and a woman brought you here. You know what I mean? She had help but she brought you here. And you think about your mom and your grandma and know how important that was in everybody’s life.

“So you got the male and the female that makes the world go ‘round,” Bobby stressed. “And they both need each other. In any case, a man needs a woman or something that takes the place of a woman as far as he’s concerned, and I say vice-versa. And if it falls apart, to put it on a bigger scale, like the world falling apart, over and over again.”

Any discussion with Bobby Womack would always turn to Sam Cooke.

“I came out with Sam Cooke,” he volunteered. “’Bobby, you need to take off them boots and galosches and ear muffs and all that stuff. You don’t need to wear that. It’s 80 and 90 degrees. It’s like this all the time. You can walk where you got to go if you don’t have no car.’

“It’s just inspirational. To me it was more normal to see movie stars and TV stars. Every now and then I would say, ‘I can’t believe it. I just watched Bonanza on TV and saw the big guy who I loved, Dan Blocker.

“I’ll tell you one story, the father on the show, the white dude, Lorne Greene. I’ll tell you how you can be a kid and that’s why this stuff has stuck with me a long time and I never could forget it.

“I was riding one day on Melrose Ave. in Hollywood, and I wished they had a black kid on Bonanza. I thought, ‘There has to be a black kid in the family. They just don’t show him. He’s probably on the back porch.’ I was making all these excuses in my head as a kid. So I just wrote myself into the script. (laughs). I was there. See, I was the kid they never saw. This is no joke. This is serious. I always listened to a lot of country music growing up. I even did an album later called BW Goes C&W.

“So one day as I was riding, just came to Hollywood with Sam Cooke, going to the Hollywood Hills, and Sam said, ‘Look to your right.’ There was Lorne Green in a sports car. Do you know, and it’s the most embarrassing thing…I started saying ‘Dad! Dad! This is Bobby!’ I’m hollering at this guy, and he says, ‘Leave me the fuck alone!’ And he drove off.

“Man that broke my heart. He just didn’t recognize me. Then from that day on I said ‘I will never ever break nobody’s spirit like that if I became famous.’ It’s like medicine you got to spread it. Like today, someone comes up and says, ‘you don’t remember but you let me open up your show.’ Stuff like that. ‘Really?’ And they’d be super artists today.

“Sam was the first guy who introduced me to Nat King Cole at RCA studios on Sunset when Nat was coming down the stairway. Sam was a very likeable guy and he knew everybody. ‘Hey Nat, I want you to meet Bobby Womack. He’s gonna be big one day. This is my new artist, Bobby Womack, who sang with a group called the Valentinos.’ They were talking like they knew each other for a hundred years. ‘Pleasure meeting you, man.’ Then I walked away thinking about it. ‘Man, I just met Nat King Cole…’

“Earl Palmer was always on the Sam Cooke sessions. He was a hell of a drummer. I knew Rene Hall. He was a hell of a soulful arranger. We worked with Sam together.

“Allen Klein was on his case about his repertoire and he would fight Sam but Sam knew Allen was the kind of guy that was always gonna speak his mind. A lot of guys were yes men. ‘Sam you can do anything. Sam you don’t worry ‘bout that. He’s not a musician.’ But Allen would come to the show and then Sam would say, ‘Oh Lord…Let me hear what he’s gonna say.’ And then when Allen would come in and mention ‘you sang the ‘Girl From Ipanema’ for an hour and people go to sleep. It ain’t you, man. People want to hear you.’ Sam seemed to wait on him to come.

“Sam had a big influence on anybody,” underlined Womack. “I mean to me, cancer would be good if Sam gave it out. I’m serious. Damn, I’ve seen artists who have their own styles, but if they hung around Sam a minute they are gonna make some of his runs. Just rubs off on you. Sam was a natural.

“He would always say, ‘Bobby, you could listen to a person talk and know what they sound like. They sound the same way they talk.’ Listen to Louie Armstrong. Listen to Jackie Wilson. Listen to Ray Charles. All these guys have different styles and don’t try and sound like each other. When you are born a certain way you can not even think about tryin’ to sound like somebody else. It would be hard to do.’’

One night at Art’s Delicatessen, I asked Bobby about musicians he heard in the sixties around Hollywood and touring the US.

“I would see a lot of guitar players. I bought a lot of equipment at Wallichs Music City and met a lot of people. Like this guitar player, a white dude, a hell of a player. He cut ‘Moonlight In Vermont.’ Kenny Burrell! I would follow him around. ‘Who is this guy?’ Damn, that cat was so bad. This guy is a one man band and could sit on stage with a drummer and bass and kill them. I liked Barney Kessel but Kenny was my hero.

“The first time I saw and met Jimi Hendrix [then James Marshall Hendrix] to really know him when he was with a guy named Gorgeous George, who was a guy who made clothes and always thought he could be a Sam Cooke or Jackie Wilson. It was on a show when I was playing guitar for Sam, on a bill with Jackie Wilson and James Brown.

“But George never had that kind of talent for me but you couldn’t tell him that. And he had Jimi Hendrix playing for him. George is going crazy and Jimi Hendrix is settin’ his guitar on fire in a routine. And George said, ‘Hey man, you’re trying to steal my gig. If you do this again and start the act I’m gonna fire you.’ ‘Man, I’m just trying to help you’ is what Jimi said, and George replied, ‘I don’t need that kind of help.’

“I met Dee Clark when we did tours together with Sam. He had a beautiful voice. Curtis Mayfield was a hell of a talent. Everybody knows that. He was before his time, really. He wrote some great stuff with the Impressions to Jerry Butler and for so many artists.”

One afternoon in 1998, I was waiting in line at a Sam Woo’s Korean BBQ on Sepulveda Boulevard in Van Nuys. Bobby lived up the street. I looked at the parking lot and arriving was Bobby. He parked his Buick Electra 225 and strolled confidently into the joint. And I knew why he was smiling and ready to nosh.

BW had the title theme and ending credits cue on Quentin Tarentino’s Jackie Brown with his own master recording of “Across 110th Street.” Womack just had a big pay day.

We embraced and he offered to buy me a head of a pig on a split at the take out counter. It sure looked scary but it tasted awfully good. Might have been literally the last time I ate pork...

At the cash register I asked about his song, “Across 110th Street.”

“I used to live in Westwood and wrote ‘Across 110Th Street’ in an apartment there. That was very spiritual to me. Man, it was easy to write those songs. I was born in the ghetto. That’s what this whole story was about.”

Later during a phone 2008 interview, I pressed him for one revealing music business tale. He laughed, “I can’t tell you the wildest crazy shit I saw in a studio because I would need an aspirin,” he confessed.

In one taped conversation Bobby and I did that year, he recalled his longtime residency in Laurel Canyon. Womack is never or rarely cited as a onetime Laurel Canyon based singer/songwriter. R&B legends Larry Williams and Johnny “Guitar” Watson along with Frank Zappa and Mamas Cass Elliot were his neighbors.

“Marshall Brevitz, my manager in the early seventies owned Thee Experience club in Hollywood on Sunset Blvd. He introduced me to so many people, and told me, ‘Man, you’re making money now. Don’t you want to get a house?’ I never thought about that. I knew I had to get my mom one and my dad one. It just made sense to have a house. It could help your credit. Marshall found me this house and I moved in. See, restaurants weren’t a big thing then. Food was just something you had to do. ‘I didn’t eat today.’ (laughs).

“Anthony Perkins lived three doors from me and I did know he was the actor from Psycho, which was a very famous movie. And I would always say this guy looked like he was always ready to take off running like he’s scared.

“You could be anywhere in Laurel Canyon and something would be goin’ on. It was like a nightclub in a sense to me,” he marveled.

“Laurel Canyon was where I lived and decided where I was gonna hang. Yes, there were recording studios on Sunset Blvd. and record labels, but I never looked at it as there’s a lot of musicians up here.

“Like, when I heard Mama Cass passed. I didn’t know she stayed right around the corner from me. I mean, right around the corner and I didn’t know it. And I was shocked but you know I was never riding around lookin’ for Mamas Cass. But I did do ‘California Dreamin’’ because I was just knocked out by the Mamas and Papas. They blew me away with it and it was such a cool song. Plus, everybody was covering a good song. The song reached me because I loved California. I didn’t have to hear it to pack my bags and come to town. I’ve been here years before I heard that tune,” he reinforced.

“I could get motivated in Laurel Canyon but you didn’t know you were getting motivated. It was just like, ‘we’re gonna hang out.’ Who was writing and who had a song. You would just jump in on a song, or the subject and you were then involved. ‘There was a sense of inclusion.

“Laurel Canyon was very secluded and very quiet. You couldn’t be driving around there and just stop by an address to stop by. You had to know somebody. That was a great place to hide out when you weren’t hiding out or just be out. Nobody was gonna call the police and say, ‘They’re makin’ too much noise.’ There were always different musicians with a different lifestyle who worked in the business in some form or fashion. That gave you so much freedom, especially when it was positive.

“See, the music of Laurel Canyon, and I’m really talking about the pop and rock stuff has longevity because it was the beginning of something that something that is a household word today,” he continued. “And these people who created it. It was a guiding post in a sense for other writers. ‘I want to get that same atmosphere.’ You dropped egos and worked together. You enjoyed the fact of creating something together. It was what was happening and we lead the way.

“I was so blown away when Woody (Ron Wood) moved out here. And we would be sitting days and nights just going from one song to another. He and I on guitars and we would do that until we were totally exhausted for hours. And then when Keith (Richards) joined, Ron moved to New York, Keith would come over all the time…

“Laurel Canyon was a hiding place and then so many people started moving in there. Then the drug scene drew a lot of people, including cops and that kind of thing. To me it was more reckless ever than it is now. Everybody thought ‘we’re young and we will pass this stage. We’re just havin’ fun now.’ But with drugs it don’t go away. It makes its own path, ‘I’m gonna be living here for a while…’

“I ran into Arthur Lee a few times in Laurel Canyon. I never will forget when Woody brought Keith Moon the drummer in the Who up to my place. I said, ‘this guy is crazy.’ Because I just got my house with my new furniture and everything, and Woody and them came by with him. And Moon come in, he was so wild, and jumps on top of my couch and start running all over it and the counter. Everywhere. So I said, ‘who in the fuck is this?’ So Woody started laughing and said Keith was OK. ‘Yea, but I just bought these couches and I didn’t nothing.’ But had never seen a guy this wild. He fell on the floor, started pouring water on himself. He was just crazy. But when I saw him play I knew that was a place where he could be himself. He looks normal. (laughs).

“Frank Zappa lived right around the corner from me. The strange thing about Frank is that he didn’t invade my space and I didn’t invade his space. He was always to himself. What happened was that he admired Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson. He was a hero of his and I didn’t know that. Johnny came up to see me one day, ‘Man, I’m going around to Frank Zappa’s house ‘cause he wants to see me and ask me about the business. I never did that thing, ‘Hi I’m Womack. I live around the corner.’ And this was like a couple of years before he passed.

“Johnny had mentioned that Frank wanted to take him on tour. A big thing. ‘Man, go do that.’ Then Johnny Watson went to Japan and he took my horn section ‘cause I wasn’t working and I was in the studio. ‘OK, I need to use your horn section.’ And he goes there and never comes back.”

In the seventies Womack crossed paths with John Lennon one memorable evening.

“I will never forget I was on the stage at the Troubadour in West Hollywood. Donny Hathaway. I walked on the stage and John Lennon grabbed the piano and I grabbed a guitar, the only thing I saw ‘cause I didn’t want to be up there doin’ nothing. And when Lennon grabbed the piano it was out of tune. And he turns around, and at the time I didn’t know who he was. ‘Cause I’m caught up in all these people bein’ on stage. And Lennon asks for me to give him the guitar. ‘The piano is out of tune.’ ‘I don’t play no piano, man. I’m left-handed. It would be out of tune worse than that if I played it.’

“So Lennon got real hot and said ‘give me the fuckin’ guitar.’ And I said something back. Afterwards he came up to me to give me an apology. ‘We were just on the spot.’ ‘Oh man, forget about it.’ And we took a picture together. I still have the picture. It was amazing,” he exclaimed.

A month after celebrating his 65th birthday, Bobby Womack the first Cleveland native to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as an individual performer.

During his 2009 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame by Ron Wood of the Rolling Stones, Wood detailed Womack’s special relationship with the band whose very first #1 record was “It’s All Over Now.” It was a song Womack had written and recorded as a member of the Valentinos, the group composed of the five Womack brothers and produced by Sam Cooke for his own SAR label. Bobby performed a breathtaking “Across 110th Street” with a full orchestra and house band. The event was a true homecoming for Bobby Womack.

“This is just the greatest, I’m extremely happy. My very first thought was — I wish I could call Sam Cooke and share this moment with him. This is just about as exciting to me as being able to see Barack Obama become the first Black President of the United States of America! It proves that, if you’re blessed to be able to wait on what’s important to you, a lot of things will change in life. Being able to work, perform and make people happy is where it’s at. I haven’t been home in almost 30 years, so having this happen in my hometown is really icing on the cake,” Womack remarked after he heard the good news. “I’m looking forward to going home.”

“With the Stones it became a family,” Bobby told me in 2008. “Like, I sing on their version of ‘Harlem Shuffle.’ I knew Bob & Earl who did the original but when I was doing the vocal with the Stones I never thought about them. Never thought ‘why did they pick that song’ I think it was Keith. After that I thought, ‘man, music is a universal language. That song was cut 30 years before.’ What happened to Bob & Earl? Barry White was involved with the original recording. But I had never met him. Then I went over to A&M to put something on a record and Barry came in. ‘Man, I love your music.’ We’d be complimenting each other.

“I can remember when Wilson Pickett told me that I had to go to Memphis. And I moved to Memphis, because I had just gotten married and I had to feel hungry for the music. And I didn’t feel hungry enough livin’ in a big old house and that atmosphere.

“In Memphis I lived in the same hotel Martin Luther King, Jr. got killed in. I enjoyed Memphis every day and a lot of people tellin’ me, ‘You got a hit record. Why don’t you go out on the road?’ I liked the idea of musicians coming in every week just to record. And you had a chance to play on their sessions and you are learning so much. Aretha, Elvis. And you catch the people in their true form. Plus I brought something in. I was at the time in my twenties and full of energy. I’d hear someone talking that blew me away and I’d write a song about it. Today I wish I had that kind of fire, I still do, but it’s an older fire. ‘It will happen tomorrow…’

“Everybody I knew in this business are no longer here…Like Jerry Wexler. I remember working with Jerry on an Aretha Franklin or Wilson Pickett session. He was such a creative guy. Jerry was the guy who knew how to bring musicians together and let them explode. And they felt relaxed around him.”

On October 4, 1970 in room 105 at the Landmark Hotel in Hollywood the performer and singer Janis Joplin died of an accidental heroin overdose.

Bobby Womack was one of the last two people to see Joplin alive after Janis and Full Tilt organist Ken Pearson on October 3rd went to the restaurant and bar Barney’s Beanery in West Hollywood for drinks following a recording session with Paul A. Rothchild at Sunset Sound studio. Janis reviewed the track “Buried Alive in the Blues” and had planned to cut vocals to the recording the following day.

“Paul Rothchild lived in Laurel Canyon. He did The Doors and Pearl, the last Janis Joplin album,” Bobby Womack reminisced in a 2008 interview.

“I loved Paul. Rothchild was at the studio and he said, ‘Man, she loves you. You guys should hang out. She’ll be good.’

“All I know is that Janis Joplin called me. I didn’t know how she got my number. ‘This is Janis.’ ‘What are you calling about?’ I didn’t think it was her. ‘Well, everybody else has recorded your songs and I just want to do one of your songs.’

“She was a person who joked all the time. ‘Why don’t you come to the studio? It’s on Sunset. Come to the studio and bring me some songs.’

“So I brought her every song I had ever written that were recorded and not recorded. And she said, ‘when I push the button that means I like it. If I don’t push the button then you gotta quit and go to another song.’ Janis did my tune ‘Trust Me.’

“So as soon as I hit the first song ‘Trust Me,’ she pushed the button. ‘Shit, this is gonna be easy. I’m gonna have the whole album’ I said to myself. She never pushed the button again…I kept on singing and ran out of songs. And Janis said, ‘Don’t you get it? The first song you gave me I loved it. That’s it. Let’s cut it.’ And I played on it.”

“Trust Me” appeared on Joplin’s album Pearl which peaked at #1 on the Billboard 200, a position it held for nine weeks. Pearl has been certified 4x Platinum by the RIAA. The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland is curating a special exhibit devoted to Janis Joplin, Pearl and more, scheduled to open May 21, 2021.

“In a little short time we became very close,” enthused Bobby in our 2008 conversation. “I remember Janis coming to the studio the next day and she was very upset because she was sayin’ ‘Jimi Hendrix passed.’ She was very upset. ‘Oh baby, I know you feel bad…’ And, I shared my own experiences about meeting him.

“She then joked about ‘Oh, I plan to kill my own self. Now with Jimi just leaving I ain’t gonna get no publicity.’ She was joking like that all the time.

“She liked my car. [“Mercedes Benz,” written by Joplin with Michael McClure and Bob Newirth, was recorded for Joplin’s Pearl sessions after she took a ride in Womack’s vehicle]. It was the last song Joplin ever recorded.

“Later, Janis said to come by the Hollywood Landmark Hotel. I go to the hotel and we were partying…

“She was very respectful. I found out a lot about her in a short time. The thing that blew me away about Janis was when she asked ‘what bothers you the most in this business as far as the black and white thing?’ And I told her, ‘every time I cut a record I try and cut a record so I can cross over to appeal. I just don’t cut the record. I just want to be able to cut a record and that’s it.’

“And I said, ‘What about you?’ ‘Everybody keeps saying I’m trying to be Tina Turner.’ That blew me away. ‘You don’t sound nothin’ like her.’ And jokingly I added, ‘You don’t look anything like Tina. Well, we both got this problem. So why don’t we do something together like a tour? You go out there and let them know.’

“I hadn’t heard this Tina thing and told her it was in her head. She was very serious. Janis loved Tina Turner.

“It’s very hard to put the racial thing in the mix with musicians. It’s deeper than that. It never fazed them. See, everybody looked out for everybody. So that never came up but only to the outside people. And that’s just the way it was. We would joke about it and talk openly about it. Anything.

“And she ran down how she went to high school and blew the school that used to think she was ugly. And she was talking about the problems she had.

“Janis was into brown, [heroin] which I don’t do, and I was into cocaine. The phone rang and she told me to go. Someone was coming to visit her. As I went into the elevator I remember hearing a guy [alleged heroin dealer] coming up the stairs…

“Paul Rothchild then called me early that morning, and he says ‘she OD’d.’ And I said, ‘You got to be joking me…’

“That just broke my heart…In talking about that was something I could never adjust too. Is seeing somebody today and losing them tomorrow.

“Damn, I keep losing people I love and didn’t know I loved them this much until they aren’t around. Maybe it’s the thing where we become messengers for some people who aren’t here. But boy, sometimes I’m telling you I need some help with these messages. Sometimes they go too fast,” sighed Bobby.

In 2014 Womack phoned and profusely thanked me for including him in my books Canyon of Dreams The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop, and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972. “Great books! Great books! Man, ‘Black Santa’ is definitely gonna take care of you this Christmas!”

In our final chat, Bobby gave me advice and hard-earned wisdom about the music and book business encouraging me to stay in both games.

“So, you got to have passion for this business and love it because anything can disappoint you. And the strongest thing can take you out but if you have a passion for the music…

“So when I look at new generations makin’ it I join them. ‘Mr. Womack. I love your music and what you do.’ But what separates everything is the music that reached peoples’ hearts. And the stories that will live on forever and they are bein’ told over and over again.”

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including This Is Rebel Music, Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For September 2021 the duo has written a multi-narrative volume on Jimi Hendrix for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

This century Kubernik wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century). Harvey and Andrew Loog Oldham wrote the liner essays to The Essential Carole King.

In November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey penned a back cover endorsement for Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada published in 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years.

During 2020 Harvey Kubernik served as a Consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood. Kubernik is currently working on a documentary about Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member singer/songwriter Del Shannon.

Kubernik was interviewed last decade by director/producer Neil Norman for his GNP Crescendo documentary, The Seeds: Pushin’ Too Hard. Jan Savage and Daryl Hooper original members of the Seeds participated along with Bruce Johnston of the Beach Boys, Iggy Pop, Kim Fowley, Jim Salzer, the Bangles, photographer Ed Caraeff, Mark Weitz of the Strawberry Alarm Clock and Johnny Echols of Love. Miss Pamela Des Barres supplied the narration. Debut broadcast on television will be in 2021.

This decade Harvey was filmed for the currently in-production documentary about former Hollywood landmark Gold Star Recording Studio and co-owner/engineer Stan Ross produced and directed by Brad Ross and Jonathan Rosenberg. Brian Wilson, Herb Alpert, Richie Furay, Darlene Love, Mike Curb, Chris Montez, Bill Medley, Don Randi, Hal Blaine, Shel Talmy, Richard Sherman, Don Peake, Kim Fowley, Johnny Echols, Gloria Jones, Carol Kaye, Marky Ramone, David Kessel and Steven Van Zandt have been lensed.