The spring and summer a slew of Crosby, Stills and Nash

The media will soon be teasing and then hailing these CS&N-centric 2019 audio and visual retail items as well as David Crosby: Remember My Name, a documentary that will be distributed by Sony Pictures Classics in the North American market. I also suspect a revised 50th anniversary package of the May 1969 released Crosby, Stills & Nash debut LP from the Atlantic/Warner Music Group label. It spawned two top 40 hit singles, “Marrakesh Express” and “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” and subsequently informed the nascent singer/songwriter movement, soft-rock and Americana radio formats will be celebrated and targeted to digital universe consumers.

Also expect a deluxe edition DVD and Blu-Ray of director Michael Wadleigh’s 1970 documentary Woodstock that includes the trio, as well as incorporating a featurette with the never-before-seen Neil Young selections from the CSN&Y set being planned this summer from Warner Bros.

CSN&Y will be heard in the Woodstock documentary and on the revised soundtrack album. It was Atlantic Records executive Jerry Wexler who first secured the rights to the lucrative soundtrack configurations in late July 1969.

“After the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival I later got the rights to Woodstock,” Wexler explained to me in a 2007 interview. “The soundtrack albums came out on Atlantic on our Cotillion label.

“There was a lawyer named Paul Marshall, he used to be our in-house council. But we parted ways. And he was not our lawyer anymore, but, nevertheless, he called me up, ‘Listen. Are you interested in Woodstock?’

“It was going to take place in two weeks. Who the hell knew what Woodstock was going to be? He said I could have the rights for seven thousand dollars. I thought about, and bought it for seven grand. I figured ‘seven grand? Let me take a shot.’ And that was it. I should have grabbed the film rights too but Warners got them,” admitted Jerry. “Thank God that I bought Woodstock.”

Last century I interviewed the philosopher/teacher Ram Dass who instructed me “to honor the incarnation,” so I’m just gonna examine the original CS&N album from spring 1969 that I first heard on an acetate pressing in February ’69 before it shipped to rack jobbers and key FM radio deejays in the United States.

During 1965-1972, my mother Hilda worked for Raybert Productions, Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider’s company, who produced the groundbreaking 1966-1968 The Monkees series for the Columbia Television division at Gower Gulch in Hollywood. She was a stenographer and also typed some of the show’s weekly TV scripts.

Over the years dubbed vinyl acetates, sheet music and reel-to-reel tapes from a slew of music publishers were on display when I made visits to the Raybert office and the Monkees’ sitcom TV set. Actors Rupert Crosse, Jack Nicholson, Dennis Hopper, Godfrey Cambridge, Stan Freberg, and Robert Walker Jr. were around the premises and Robert Forster when he starred in the 1972 show Banyon.

My dear friend, collaborator and neighbor in Southern California, Henry Diltz was the second season photographer for The Monkees and we were around the Gower lot for their landmark counter-culture film, Head.

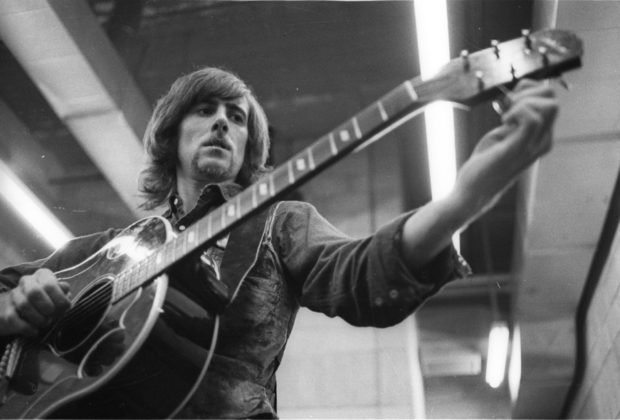

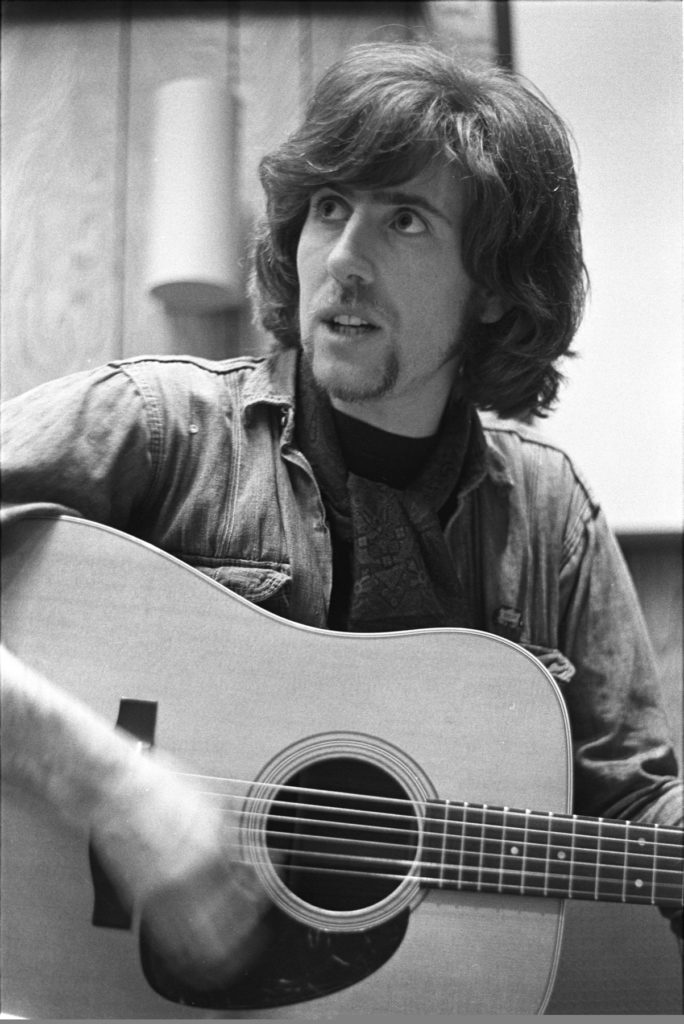

In February 1969 Diltz took photographs at graphic artist Gary Burden’s house in West Hollywood of the CS&N members and Henry snapped their front cover album picture just before they agreed on a name for their group.

The resulting portrait on the front sleeve, left to right, parades Nash, Stills, and Crosby in the reverse lineup of the subsequent LP title. The location was an abandoned house in West Hollywood at 815 Palm Avenue. Following the shoot, the outfit finally settled on their name, Crosby, Stills and Nash. Immediately afterwards, they had some concerns about the selected cover image, and quickly went back to the same house to re-shoot the cover but this time in the correct order. When everyone arrived for the re-scheduled session the house had already been leveled.

In the last week of August 1969, my brother Kenneth and I sat up front at L.A.'s Greek Theater. We’re teenagers but even we recognize that this particular concert has a gravity that distinguishes it from previous rock 'n' roll shows we’ve attended, where little was at stake beyond experiencing a dizzying euphoria. This night's music insisted on our undivided attention, that we sit up and listen, really listen.

A beguiling young singer/songwriter from Canada strolled onstage. Accompanying herself on guitar, Joni Mitchell's unerring command of mood, of tempo, of temperament, her reverence for the deeply personal as a means to explore the universal, showcases a talent of a higher order. The audience was now suitably primed. She was followed by the headliners, fresh off a tumultuous success at Max Yasgar's upstate New York farm - Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. What Ken and I recall most clearly were, of course, those exquisite vocal harmonies; the finely-wrought arrangements, as well-calibrated as an Oyster Rolex; all those gleaming guitars - acoustic and electric - lined up like a phalanx of artillery ready to rumble; Neil, sitting at a Hammond B-3, smearing chords while "Sea of Madness" crackled like thunder.

We’d seen Neil Young and Stephen Stills on April 29, 1967 in the Buffalo Springfield, once with them opening for The Supremes (!) at the Hollywood Bowl.

In June 1966, Nash and the Hollies met the Mamas and the Papas. After a Hollies’ press party event was held at Imperial Records. Rodney Bingenheimer invited Graham Nash to attend a nearby Mamas and Papas recording session of “Dancing Bear” at Western

In February 1968 the Hollies played a special Saint Valentine’s night gig at Hollywood’s Whisky a Go Go. Micky Dolenz introduced the show. Stills and Crosby were in the audience. On April 27, 1968, Crosby subsequently connected Nash to Stephen Stills, and then Crosby, Stills and Nash were formed. By the end of 1968, the Hollies’ co-founder and co-lead vocalist Graham Nash took leave, content to consider his future from the restorative oasis that was Laurel Canyon. With Crosby and Stills they unleashed a musical juggernaut that has, for fifty years, remained an ineffable presence in the cultural firmament. Given the grandiosity of his partners’ personalities and the swirl of melodrama that attends them, Graham Nash’s quiet dignity stands out like a beacon of sanity in a sea of madness. He’s always a gentleman and a candid interview subject. In September 2013, Nash published his autobiography Wild Tales: A Rock & Roll Life by Crown/Archetype. This century I’ve conducted two extensive interviews with Nash and asked him about CS&N and Laurel Canyon.

Some portions of our dialogues were published in 2009 book, Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon.

Graham and I were guests on the National Public Radio series World Café that examined the history of Laurel Canyon and we were also spotlighted on the BBC Radio 4 program California Dreaming, Laurel Canyon. “You know, kid, the truth is there’s a part of me that really believes none of this would have happened without Rodney. Incredible music has been made from that moment,” Graham volunteered in a June 2014 phone call from Hawaii. To demonstrate what kind of mensch Graham is, in his book acknowledgements, Nash listed Rodney Bingenheimer, “who helped the story to unfold,” immediately after the Everly Brothers and the Hollies, and above the names Cass Elliot, David Crosby and Stephen Stills.

Q: In 1966, Rodney told you about a Mamas and Papas recording session after a record label gathering for the Hollies.

A: I only went with Rodney to see Michelle. But Michelle, Denny (Doherty) and John (Phillips) were doing an overdub in the studio, and Cass was outside the studio. I started talking to Cass. She asked me what John Lennon would think of the Mamas and Papas music. “What would he think if us?” And I said, well, knowing John a little, I mean, who did know John, I’d known him since 1959. I told Cass that he would probably put you down at first and keep you at arms’ length until he said something funny or something bright. “OK. I can let my guard down and let these people into my inner circle.”

So I told Cass he’d put them down and not praise them. She started crying…After I had consoled her from crying from my response to her question about John, I didn’t realize that Cass had a big crush on John. Not only did she admire him and love his music, she loved something about him. I didn’t know that. So when I answered her she started crying. And, I’m going “holy fuck. Not the way you want to get off with somebody.” So then in the hallway down there at United Cass said, “What are you doing tomorrow?” “Well, I don’t think we’re doing much.” We were staying in Hollywood at the Knickerbocker Hotel. And she picked me up around noon in her convertible Porsche. I said, “where we going?” “We’ll be there in five minutes. Don’t worry.” And drove me up to Laurel Canyon and I met Crosby. And once again, my life has never been the same.

Q: You always loved Laurel Canyon and Hollywood from your visits with The Hollies 1966-1968.

A: It not lost on me that you can be in the Laurel Canyon from Hollywood in 5 minutes. Not like in England where it’s 90 minutes that’s to get to the nearest bus stop. So I was in heaven. I was free. My first wife and I were getting divorced. I had already separated from Rose. I was a free man. And I must tell you that I took to the Laurel Canyon scene like a duck to water. It was just amazing to me that these bunch of people would be living in this kind of very rural area.

I just felt so free. And more importantly, I felt appreciated. And that goes a long way with me. If you know what it is I can do and you appreciate that, I feel a lot better about things. And it seemed to be the Hollies’ reputation in the Laurel Canyon scene was a big one. I gotta tell you, I spent the first ten years in America kind of trying to separate myself from the Hollies. You know. In all truth, it was a great band. The Hollies were a great band. Unbelievable. Bobby Elliot is a fantastic drummer.

A lot of people used to say to me, “you’re leaving the bloody Hollies? Are you fuckin’ crazy? All those hit records, money and that stuff.” They had not heard what I had heard.

Coming to Los Angeles after leaving the Hollies was a geographic re-birth. I think so. I remember the first time I ever came to Los Angeles. It was paid for by Cass. And it went like this. The Epic Records contract with the Hollies was coming up and completed. Cass knew this and she figured that Lou Adler, through his Ode label would want to meet with us. So, Cass paid for first class tickets for all the Hollies to come to Los Angeles. I get out of the plane, walk down the ramp, leave the United Airlines terminal and climb the nearest palm tree. And I remember thinking to myself, “I’m never going back.”

I just decided for some reason, whatever consciousness is running this planet wanted me to be in Los Angeles. And I was gonna take full advantage. And I wasn’t quite sure what was going on, you know, what my future would entail. But I trusted myself, because my parents always told me and taught me to trust myself. I discovered Henry Diltz through Cass and the Lovin’ Spoonful through Cass. So pursuing this new musical project I was in heaven. I’m a musician, first and foremost. I’m a believer in beauty. I’m a believer in the fact that truth and justice will prevail in the end. I’m a believer in all that. I never expect anything. I had friends whose fathers went away to work and would come home and the fuckin’ house was gone. So, English people probably eat everything on their plate because they never knew when the next meal was gonna come. Years previously food rationing was just a drag. I never starved. I went hungry often, but I never starved. But it was basically bangers and mash. Cheap stuff. A cup of tea would really go a long way to calm you down.

Q: I’ve always heard that the Hollies in 1968 weren’t into your tunes at that time.

A: The music always kept me going. I don’t know what I would have done. And I don’t know where the fuck I would be if it hadn’t been for my love of music. And thank God, my mother and father appreciated my passion. Appreciated the fact that I would give up everything to be able to play music. And they supported me in that. The Hollies passed on “Teach Your Children,” “Lady Of The Island,” “Marrakesh Express” and “The Sleep Song.”

What happened was that I’d written this song “King Midas In Reverse,” probably one of my earliest, real songs. You know, I’m talking about myself. I’m talking about what I think about my life. And how fragile it all is. And although we made a great record of that song, which is the third song in my box set, it kind of failed by their standards. I mean every Hollies song that we made kind of went into the Top Ten. “King Midas” didn’t. And at that point they started to lose their faith in the direction that I personally wanted to take the band. They did an album of Bob Dylan covers, Hollies Sing Dylan. My voice is on “Blowin’ In The Wind.” It’s one of the reasons I knew that my time with the Hollies was up. I mean, totally Las Vegas. When I joined David and Steven I didn’t talk about my time with the Hollies. It’s almost like you don‘t talk to your new lover about your past lover. You just don‘t do it if you’re smart. My relationship with the Hollies was pretty sour after I left, obviously. They felt that I deserted them. I personally felt very bad about leaving my friend Allan Clarke behind. For the first ten or fifteen years I had been with David and Stephen I didn’t listen to any Hollies music. And then I got sent 60 Hollies’ tracks from BBC radio broadcasts we had done. Obviously, radio, one take, live, mixed to live for the radio, no second chances, no overdubs later. And I began to realize that we were a great fuckin’ band. We were really energetic. We were musical. We were accurate. We had written some really good pop songs for want of a better word. And I began to realize that we were indeed a great band.

Q: In 1966 you wrote “Marrakesh Express” intended for the Hollies and they did the first version of it.

A: I’m in England. I’ve been reading about William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg with Peter Orlofsky and they’re having a great time. “Boy, that’s sounds like a great idea. I’m going.” So, I grab my wife, Rose, and a dear friend of ours, Joanne, a friend of Rose’s, and we went to Morocco. And took the train down from Casablanca down to Marrekesh.

All my pores were open. I was just soaking in this atmosphere. Soaking in this train. I was in first class with Rose and Joanne and a couple of older American ladies that had blue hair. I was carrying all these tunes in my pocket just waiting for the right moment. Waiting for the appreciation. Ashley Kosak was Donovan’s manager, and Donovan was the one who taught me to fingerpick. And it was Donovan that first really gave me my first inkling that I could be an independent artist. I was still in the Hollies, of course, and both Ashley and Donovan encouraged me to keep writing and make a record myself. Laurel Canyon informed myself and Donovan psychologically, spiritually and musically. One of the first people, apart from Donovan and Ashley was Crosby. In a way, and I’ve said this before, he saved my ass. He saved my life. When I was in the Hollies and writing “Teach Your Children” and “Marrekesh Express” and they didn’t want to deal with them, you know, it made me question myself, and that’s the worst thing you can do to an artist. And so Crosby is looking at me with that impish smile, “They’re fucked, man. Don’t even listen to what they are saying. They’re totally fucked. I love those songs.”

Q: “Lady of The Island.”

A: OK. (laughs).Three ladies in my life. My first wife Rose, Joni and John Sebastian’s wife Laurie. I had it and wanted to do it very simply. I’d already played it for David and he loved it. We sat down. One take. That’s it.

Q: This was a departure from the songs in the Hollies.

A: I was completely free. And it was an amazing to me. Very often I’ve said I’m one of the luckiest men in the world. I know a lot of people think that way about their life, but it’s really true to me. I’m really an incredibly lucky man. I must have done something right somewhere. I don’t know what the fuck it is kid. But I must have done something. It’s an incredible story, isn’t it?

Q: You also had, a bit of a lifestyle difference with the Hollies. You smoked pot and they didn’t.

A: Yeah. We were drinkers in the north of England. And in all of England. Because of the unavailability. What we would do is drink. You’d go down to the pub and see your friends. It became sort of a comfort thing that would be taken to access. Of course, people would get blind drunk.

Q: When did you first see reefer?

A: Let me see…Reefer is different than hash. In England you couldn’t get good grass. It was too hard and too bulky to smuggle. And we were so much closer to the hash producing countries of the world. So in England it was mainly hash and I would smoke that. I had a friend who was a William Morris agent and we shared an apartment in London and get very high. Never mixed it with tobacco. I never smoked cigarettes so it would kill me to try and put it in tobacco. So I had a bit of a difference in lifestyle. Yes. I think it pushes you in different directions.

Q: The year 1969. How was it for you? Where were you living and hanging out with?

A: I think that my time with the Hollies was done. And I knew that instinctively. That was a little tense. I left them on December 8, 1968. On December 10th I was in Los Angeles with David (Crosby) and Stephen (Stills). I end up at Cass Elliot’s house. Cass’ house was kind of a central point for a huge amount of very bright and very colorful people. Basically, I was hanging out with David and Stephen. And Cass.

I didn’t know many people. I knew Henry Diltz, since he took photos of the Hollies in 1966. In terms of friends, I only really had David, Stephen and Cass and Elliot (Roberts) probably. December 1968 as I said before, I was with the Hollies and by December 10th I was in Los Angeles with David and Stephen. We went to New York to SAG Harbor to our friend’s John Sebastian’s place and John was being recorded and produced by Paul Rothchild at the time. Which is how I come to be on John’s first record.

In fact, John was almost going to be a member. We sang with him. We were in New York and Paul Rothchild was in New York. We had already blown Paul’s mind. Because he was a great record producer and he could really hear a hit. He had heard one after another of great songs. So he says, “Come on. Let’s go into the Record Plant in New York.”

In December of ’68, CS&N and Paul Rothchild went into the studio and recorded two songs. “You Don’t Have To Cry” and “Helplessly Hoping.” And they’re pretty stunning.

Q: It’s quite obvious with all the future rescue work you did with and for David Crosby that it was just as deep for the things he did for you as well.

A: Absolutely. Correct. I will never be able to repay David for what he did when the Hollies were refusing my material and I was incredibly depressed about it. He really saved my life. By supporting me. By appreciating the music that they didn’t want to record. I mean, Crosby has been there for me at the very beginning.

When I first came to America I didn’t bring any money. It was months before my money from my bank account and the Hollies made it through all the financial scenes of being transferred to a different country. I borrowed $80,000 from Crosby and he never batted an eyelid. It was a big ego blow for David to be thrown out of the Byrds. What did he do? He went and bought a boat and started living on it in Florida. His life was pretty cool.

Q: And how did it feel being the only Brit in a group with two Americans?

A: I felt pretty good about it. Because, you know, I have a decent sense of humor and I have a decent understanding of how the universe works. And I was faced by these two, and they really were Americans. Crosby was so fucking American. American attitudes. American ego. And Stephen was the same. I must say, I was completely bold over. I admire Stephen and love him dearly, but Crosby is a different animal on this planet. And I recognized it from the very first moment I ever met him. Which of course was through Cass. I was with two real Yanks. Absolutely. I was with two Americans of doom.

I felt fantastic. I know that because of the British invasion and what British music was doing to the American scene, and how admired British groups were by American groups, I felt pretty confident in myself. You know, I happen to believe, and this is not ego talking, I’m pretty good at what I do.

You gotta understand. David, Stephen and I came from harmony bands. I mean, we were harmony freaks. So although, as I’ve said before, CS&N never had any claim on any of the notes that we sang. It’s just when that sound happened it was instantly recognized by me, David and Stephen as something stunning.

Q: As a manager you initially wanted Larry Kurzon, who was then with the William Morris Agency and a good friend from London. But David Geffen and Elliot Roberts were warming up in bullpen to take over the game.

A: Larry was completely blown out of the water by Geffen and Roberts, because they were sharks. I loved Elliot. He was an incredibly funny man. You know, he should have been a standup comedian. He really should have. With any balls he should have. He loved the music. Don’t forget, he was already managing Neil and he was already managing Joan. So we knew that he had incredible taste.

When David (Crosby) was producing Joni’s first record, obviously he was one of Elliot’s best friends. And so, it made sense that Elliot, who managed Joni, managed Neil, was best friends with David, knew Stephen, it was obvious that he would be our manager. Then we needed business acumen that wasn’t there in Elliot at that point.

So we arrange a meeting with this guy David Geffen. I’m in New York. So we go to this building that is 58 thousand stories tall and go to the 28th thousand floor. When we get out and meet Geffen in his office, well, there’s no desk. And I loved that. I thought, “Wow, this guy is fuckin’ cool. He doesn’t even have a desk.” He’s not sitting behind it two feet above us and looking down on us. This guy is real. It’s only years later I find out that not only did he not have a desk but it wasn’t even his fuckin’ office! Geffen had borrowed it for the meeting. When they both said to us “Listen. Do what you do. Leave the rest to us. We know how to do this. We know what this means. We know how to position this. We know how to promote this. Do what you do and leave the fuckin’ shit to us.” And that was fine with us.

Q: I know you wanted to be on Apple Records and at a late 1968 or early ’69 rehearsal in London played the bulk of the projected first album tunes on acoustic guitars for George Harrison and Peter Asher and they passed.

So give me the run up to actually recording the CS&N debut LP for Atlantic that was done at Wally Heider’s studio on Cahuenga Ave. Bill Halverson did a stellar job engineering it.

A: When I first went in there I thought. It was small, it was funky. I never met Bill Halverson. We got in Crosby’s Volkswagen van and drove up to the studio and brought our guitars and amps out and started to make the records.

We knew that we had fabulous songs. I would never play anybody a song if I didn’t feel two things: One that it got past me. And two and I would hope that it would be interesting for you to hear. So I have those two criteria whenever I’m writing. First of all it has to get past me. I have to figure out whether the song has to resonate, has a reason for existing, and after that, do I want to put this on to somebody else? And the answer to those two questions is yes then you’ll get to hear the song.

Q: What do you recall about the making of the first CS&N album?

A: Everything. Cass sings on “Pre-Road Dawns.” We found a spot for her to join on us a vocal. “Be sure to hide the roaches.”

Q: “Pre-Road Dawns” starts because of a tuning I had just learned from Stephen that the “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” is in from the top strings down. “Four and Twenty” is in that tuning as well. So I was playing around with that tuning one day at Joni’s house and I was beginning to realize two things: First of all, she had her own career and she would have to go on the road at some point.

Even though we were together right then. And, at some point, this record took off like we knew it was going to do, that we would have to go on the road. And that made me kind of sad. Because I know what the road is. And it can be a lonely place. And so “Pre-Road Dawns” was me feeling down about having to go on the road. We recorded it and then Stephen said, “You know, why don’t we put in roaches and midnight coaches?” And this is Stephen, which is really unusual because he was not a smoker at all. Crosby and I were the only smokers. He helped me with that chorus. That’s where Cass came in.

Q: Did you know there was some magic happening?

A: When I first heard “You Don’t Have To Cry,” a Stephen Stills song. That’s the brilliance of Stephen Stills, man. When I first heard the “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” I couldn’t believe it. As a songwriter and as a performer I could not believe this song. It was stunning in its composition. It went this way, and then it went that way, then it sped up, then it slowed down and then it peaked. I couldn’t wait to record it.

As a matter of fact, when we got to the end of the album, and I think we had mixed three quarters of it, Stephen comes into the studio and he goes, “I wanna re-cut it.” I said, “What?” “Yeah. I’m not sure that we got it.” Well, I got it. It gets me. If you want to re-cut it, fantastic. Let’s go to it.” We spent 22 hours re-recording the “Suite” and never used it. It’s not lost on me that I am coming from Laurel Canyon into Hollywood to record. And sometimes I would walk from Joni’s house to the studio. I was in heaven. I was a musician making music with incredible people with a bunch of incredible songs and the freedom to keep everybody out of the studio that would fuck it up. The neighborhood was Mickey and Samantha Dolenz. They were close. David Blue, he was crashing at Elliot Robert’s house, two houses up from Joan. We would go to the little Italian restaurant at the Laurel Canyon Country Store. We’d go to Art’s Delicatessen, to Canter’s Deli, Joni would cook dinner. We’d go to Greenblatt’s Deli. Musso & Frank Grill. Joni loved Crosby, Stills and Nash as much as we did. She was the very first person on this planet to hear that sound. Just me. We did go and sing for Cass but the very first time was in Joni’s living room. We knew that we had these songs to do. That if we got as live as possible, and as immediate as possible the very essence of the song down, and the expression is there and the emotion was there, and the slight retards and the slight speeding ups that you need within a piece of music sometimes, once we had that essence down, and we looked at it, and then added more voices to that, and then maybe added a guitar or something it took on a life of its own. This album kind of made itself. We had the songs. We had the energy. We were happy as fuck. All of us, Stephen was going out with Judy (Collins). I was with Joni, and David was with Christine. (Hinton). How better could life be? And Crosby had a lot to do with the best herb. (laughs).

Q: And not to be lost around the songs is the musical playing, particularly things Stills implemented like backward guitar solos that weave in the words and voices.

A: I must tell you that Stephen Stills was an incredibly impressive musician at that point. He played everything. He was an amazing musician. And generous. And one of the things that we loved was that there were no rules. And there have never been any rules. And there will never be any rules in CS&N. It doesn’t matter who sings, maybe we switch in the chorus, ‘you sing the high part and I’ll sing the low part.’

There were never any rules. And so when Stephen said on “Forty Nine Bye Byes” and putting his guitar backwards. I sat that and watched him and going “How the fuck does he remember the chords backwards?” So that when you then flip the tape back to play the real way that his guitar, not only would be backwards with this incredible sound, but would change with every chord change. It was an amazing thing to see Stephen do that. To see Stephen do the guitars on “Marrekesh Express.” I’d never seen anybody do anything like that. Like, living in Laurel Canyon. There’s no way to describe it. My life was unbelievable on every level. Not only as a musician, but as a lover as a friend, as a songwriter. My life was unbelievable at that point. I would be going and recording “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” with David and Stephen and then bringing tapes home and playing them for Joan. And having her absolutely get it.

I mean we would do normal stuff. But what was happening is that with Joni writing so much and me writing so much, and with Joni recording and me recording we didn’t get a lot of time to socialize a lot. But people would come by the studio like Henry Diltz, who had an open invitation to come by at any point, you know.

Q: You didn’t perform live or work out the material before cutting.

A: No formal rehearsals before we went into the studio. Our rehearsals consisted of private going through the tune, and then saying, “Fuck, let’s go to (Peter) Fonda’s house. Fuck. Let’s go to Paul Rothchild’s house. Let’s go to Alan Parisier’s house. Let’s go and sing them this shit!” Eventually we could sing that entire album on a couple of acoustic guitars and blow people’s fuckin’ minds.

Q: And then it was time to take it on the road. I know Paul Harris a piano player and bassist Harvey Brooks were considered, along with keyboardist Van Dyke Parks, who at the time didn’t want to tour. And then Neil Young joins the team.

A: When we finished the album we realized that we would have to go out and play live. We knew it was going to be a hit when we walked out of the studio and gave the two-track to Ahmet Ertegun. And I have a photograph of David and Stephen outside the studio with Ahmet at that very moment. We knew it was going to be a smash. We just knew. Ahmet got it immediately. He listened to that music and said, ‘Ah fuck…I want.’

So they worked it out between Geffen and Ahmet. I was on Epic, Columbia wanted Poco, and there was a trade and we all ended up with Ahmet, for which we were incredibly glad.

But we realized we would have to go out and play live. OK. So, we’re talking about this. And, Stephen says, “Man, I really need to spark off somebody. You and David are pretty good rhythm guitar players but man, I wish we had another…Somebody, maybe an organ player that I can jam with and solo.” We talked with Stevie Winwood. We talked with Van Dyke Parks. We needed somebody just to keep Stephen on his game and competitive and on fire.

“And I think basically that Stephen and Ahmet came up with the idea of or maybe it was Ahmet to Stephen, was getting Neil on board. I was the only one reluctant to bring Neil into the band. And the reason was that we had spent the last few months making this incredible record and developing this beautiful harmonic sound, right. But Neil wanted to be more than a musician for the road show.

I can’t commit this. I know who Neil is. One of my favorite songs is ‘Expecting To Fly’ from Buffalo Springfield that he did with Jack Nitzsche. Listen to it. So I knew who Neil was and I loved this fucking song. I was a big fan of the Buffalo Springfield. How could you not? I listened to Buffalo Springfield. “On The Way Home.” That’s a great one. “For What It’s Worth.”

But I said I can’t commit to this until I meet Neil. I gotta sit down with this cat. I wanna know who he is. I wanna know if I can go on the road with him. I wanna know if I want him to be a part of my life. And, that made sense to them.

So, at a coffee shop on Bleeker Street in New York I went and had breakfast with Neil. After that breakfast I would have made him the President of Canada. He was incredibly funny. He had an incredibly dry sense of humor. He always had a bunch of songs that I loved, “Expecting To Fly” being the primary example. And at the end of that breakfast and walked down to the Village Gate where we were rehearsing and I said, “OK.” “It was obvious that this man was as serious as a heart attack about his music. It was obvious by hanging out with him that he was destined for great things. And it was obvious by hanging out with him that he could put a fire under Stephen that we needed. “Well, have you ever seen me and Stephen play together?” “We used to start acoustic on the debut tour. We would begin with “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” and blow their minds. What would happen is that the curtains would open and there would be a line of Martins, and the drums and the bass. And then we’d say, “We’d like to introduce you to our friend, Neil Young.” And the place would go fuckin’ bananas, right. We rehearsed for the first tour on the Warner Bros set of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They in Burbank. So, it was pretty obvious from the sounds I was listening and the way that Neil was affecting Stephen that this would be a really great thing. And when we got to the Chicago Theater I think on August 12th1969, and there was a young kid in the audience called Danny Folgelberg, who at that concert decided that he wanted to be a songwriter and a player. And we’re so fucked up we had Joni open for us! The music got better on stage. Because we were actually doing it, and I didn’t know where it was gonna go after they started playing.

Q: Reflections on the Woodstock Festival.

A: The rain, and the mud, and the getting together of a half a million people that thought the same way that we did. Hanging out backstage in John Sebastian’s tent. Landing in the helicopter that had a couple of problems. Getting into the tent and of course John breaking out his best stash. And then realizing that nobody there has ever seen our band. And this is the Grateful Dead, The Band, Ritchie Havens, John Sebastian, Santana. None of them had ever seen us. They loved the record and they were all going, ‘well, you know, fuckin’ show us.’ ‘Shit or get off.’”

In examining the Crosby, Stills and Nash, I asked some folks in 2019 about the impact the CS&N long player had on them in 1969.

“It's funny,” reminisced writer Gary Pig Gold, “but the very first ‘real’ job I ever had in the Summer of ’69, delivering Globe and Mail newspapers at dawn round the neighborhood with my 6 transistors strapped to the handle bars, I distinctly recall ‘Marrakesh Express’ broadcasting direct from CHUM-AM Toronto and thinking ‘Wow! The Hollies have made a GREAT new record!!”

“Marta Kristen, who played ‘Judy Robinson’ on Lost in Space turned me on to the Byrds in 1965,” enthused Laurel Canyon resident, actor, multi-instrumentalist and songwriter Bill Mumy, who has released nearly a dozen solo albums.

“And they quickly became my favorite group. (The Beatles stopped being considered in the ranking as they were always light years beyond anyone else). I had been a devout folkie as a young lad, studying and absorbing the entire Kingston Trio catalogue, so when I heard the harmonies and grooves the Byrds brought to folk music along with some songs I was already familiar with, they really connected with me in a life altering way.

“I bought a Rickenbacker and plugged it in. And then by the time I was in the ninth grade, along came Buffalo Springfield… Their sophomore album, Buffalo Springfield Again, remains almost perfect in my opinion and was a huge leap forward to me and the friends I made and listened to music with. The three guitar lineup of Neil Young, Stephen Stills and Richie Furay worked fabulously and driven by the mighty rhythm section of Bruce Palmer on bass and Dewey Martin on drums, the Springfield really rocked and they certainly upped the ante of what we called ‘folk rock.’ “Things change. Crosby was booted from the Byrds. Neil splitting Buffalo Springfield one time too many caused them to dissolve. Super Session with Stills and then Poco (Pogo) was really great stuff. But Crosby, Stills and Nash??? INSANE. TOO good,” reinforced Mumy, a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, who appeared in eighteen feature films. “That first album remains untouchable. Every song. Every track. Those VOCALS. It blew my mind. I worked hard figuring out all those guitar parts and still, probably never got em right. What were those tunings? David Crosby always makes anything he’s a part of very special and unique and he surely shined with ‘Guinevere’ and ‘Long Time Gone’ and ‘Wooden Ships…’ Stills was at his absolute peak. He truly was the King of the Hill for that album. His musicianship and songwriting and tenacity can be heard on most every bar of every song. But it’s the British gentleman Graham Nash who truly dots all the i’s and crosses all the t’s… “I had heard ‘The Frozen Noses’ demos that Stills and Crosby had produced before Nash came along. They were very cool. But they were not even in the same solar system as those songs occupied after Graham joined. His blend with Crosby is magnificent. The melodic pop sensibilities he contributed with ‘Pre Road Downs’ and ‘Marrakesh Express’ kept the flow and the glow going and ‘Lady of the Island’ is about as good a love song as it gets.

“Graham Nash gave up his entire life in England to be a part of this band and this music. And he deserves a huge thank you for it. Nothing was ever the same for those three talented guys after the first album. For better and for worse,” posed Mumy, who has worked with the pop group America off and on for over thirty years, composing, producing and performing with the band.

“August of 1968. I had bought two albums on that monsoon afternoon at The Groove Company next to Sherry’s on Sunset Boulevard (the site of the 1949 assassination attempt on gangster Mickey Cohen),” remembered musician, writer and producer, Jan Alan Henderson, author of Behind the Crimson Cape: The Cinema of George Reeves and Speeding Bullet: The Life and Bizarre Death of George Reeves. “The Soul Crusade of the Mandala, and Last Time Around, the last long player by one of my favorites, Buffalo Springfield. As I walked along Sunset Boulevard it was hard to come to grips with the demise of the Springfield. It wasn’t so long ago that I remembered members of the band waiting for their then manager, Charlie Greene, on his driveway just west of Laurel Canyon. Seeing them supporting the Rolling Stones at the Hollywood Bowl in 1966, marveling to Buffalo Springfield Again at holiday time in 1967, and now wondering what would happen to the band members after their last time around. We move forward by coming from! “Spring of 1969. The debut single ‘Marrakesh Express’ from the first Crosby, Stills & Nash album was flowing from car radio speakers. Neil Young had gone solo, and Richie Furay was a founding member of Poco. After another viewing of Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda Us and Them anthem Easy Rider, I was cruising a deserted dirt road in the Malibu mountains. It was a hot clear night, illuminated by a summer moon and the FM radio was crisp. Out of the blue and into night came Crosby, Stills and Nash with a track that was new to my friend and me, ‘Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.’ “It wasn’t the usual blues-based boogie workout. It was what would be termed ‘unplugged music’ a dozen years later. With its cascading guitars, tight harmonies, carefree breeziness, and unique equalization, the track was a bright relief in a soon to be dark world. Set against the Vietnam War, students being shot on college campuses, and grisly murders on Cielo Drive, this music gave us hope for the future,” underscored Henderson, a longtime Laurel Canyon fixture. “Stephen Stills and David Crosby were experimenting with their ‘Frozen Noses’ project when Graham Nash, refugee from the popular English invasion band The Hollies, came into the fold thanks to Mama Cass – and magic happened. Naturally! Stephen Stills was the multi-instrumentalist on the first record, and the cover was photographed by Henry Diltz at a soon to be demolished house in West Hollywood, around the corner from my godmother’s house.

“A second album with Buffalo Springfield guitarist Neil Young followed, and a live album was on the horizon.

“Musical magic in a world turned upside down. Those records were the soundtracks of the fading Sixties into the dismal Seventies; the last rays of a cultural sunset.”

“I loved the Buffalo Springfield from their first LP and so was really disappointed when they broke up,” disclosed musician and writer, the Melbourne, Australia-based pop culture historian David N. Pepperell.

“David Crosby leaving the Byrds was a huge blow too. So when I heard Crosby and Stills had got together to form a genuine Supergroup with Graham Nash of the Hollies (!) I couldn't wait to get their first album,” he enthused. “It did not disappoint.

“From the first clanging guitar chords of ‘Suite: Judy Blue Eyes’ I was totally hooked and the joys just kept on coming!

“Not since Highway 61 Revisited and Revolver had an album knocked me out like Crosby, Stills & Nash - it was the Beatles with an American twang, as much the Byrds as the Buffalo Springfield plus a high keening choral note that could only come from the Hollies. Every track a gem - all killer, no filler - and the celestial harmonies filled my eyes with tears.

“I remembered ‘Wooden Ships’ by the Airplane - the ultimate post-apocalyptic nightmare tune - but CSN just gave it much more meaning, a poignancy that tore at your heartstrings.

“Nash's gorgeous ditties – ‘Marrakesh Express’ and ‘Pre-Road Downs’ - brought Manchester to Monterey and ‘Lady Of The Island’ along with Crosby's ‘Guinevere’ are timeless songs to love - both new and lost. Stills songs - all seemingly inspired by his failed romance with Judy Collins - are heartrending, but we all know what he means and that makes the songs so personal to us.

“It's unusual for me to mention all the songs on an album I am talking about but on Crosby Stills & Nash every track is worthy of comment and the LP is an organic whole, not just a collection of tunes.

“Stills plays bass, keyboards, guitar and sings in an amazing feat of musical virtuosity and it's a shame he was never able to equal such brilliance on his solo LP's.

“No matter, Crosby, Stills & Nash will live forever in the lustrous glow of this wonderful record and 1969 will live forever in its grooves,” emphasized Pepperell, a pioneer in bringing independent music to the retail world in Australia.

“Back in the day the first CS&N LP was seen as a badge of honour to own the album,” suggested the Melbourne, Australia writer, author and roots music scholar, Michael Macdonald.

“It generally meant you had discerning ears and were pretty hip. ‘Marrakesh Express’ and ‘Suite: Judy Blue Eyes’ got heavy radio rotation at the time and, in some ways, were ushering in the 70s. I'm sure Henley and Frey listened to the album intently.

“In many ways, Stephen Stills was

“After Manassas, Stills cranked out a number of dull albums that went nowhere. Curiously, the album he did with Judy Collins in 2018 wasn't so bad. At least he sounded interested and involved.”

“In

“I didn’t know anything about where they had come from, but I quickly (like halfway through the first listen to ‘Suite: Judy Blues’) came to worship them for their harmonies, their songwriting, their message

“Ted Krever, a friend in my college dorm (it’s his voice on the Woodstock soundtrack/film going ‘Yeah,’ after the announcer introduces CSN&Y) explained the origin story of the group. I already liked the Byrds and the Hollies and he turned me on to the Buffalo Springfield (I was supposed to see them in November ’67 as an opening act for the Beach Boys, but the night before the show, Bruce Palmer was deported.) I became a big Buffalo Springfield fan too.

“Nearly 50 years later, I’ve seen CSN&Y in just about every combination except the Stills/Young Band. Crazy Horse even played my college auditorium without Neil. Obviously, their musical legacy is secure. They mattered then. They changed the landscape. Their music endures and still can delight us with its melodic/harmonic magic and lyrical meaning.

“If they could have stayed together for ten years and made a dozen albums of their best songs, they would musically have been to the 1970s what the Beatles were to the ‘60s. It really doesn’t get any better,” underlined Leaf who is currently finishing a film on Dion (Born To Cry), and since 2010, has been a professor at the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music where he teaches courses in popular songwriting, rock documentary

HARVEY KUBERNIK is an author of 15 books. His literary and music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018.

Harvey Kubernik’s The Doors: Summer's Gone has been nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections Awards for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research.

During December 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Harvey Kubernik and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz.

This century Harvey penned the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish. Kubernik’s writings have been printed in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats and Drinking with Bukowski. He is the project coordinator of the recording set The Jack Kerouac Collection. In November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.

Photos by Henry Diltz