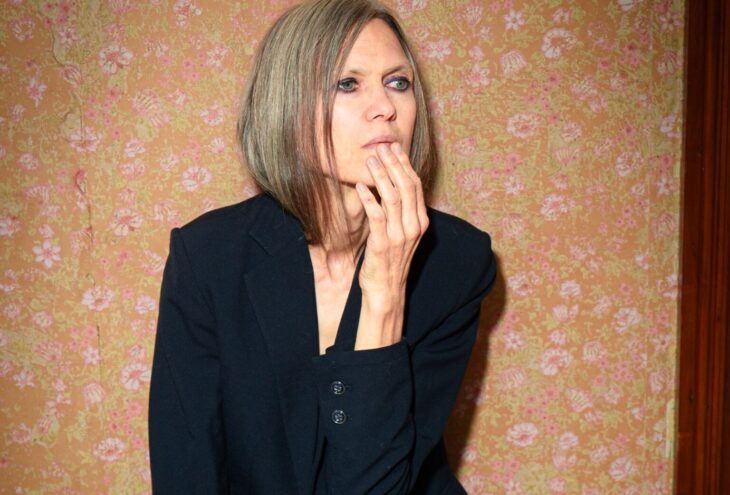

Kickin’ it indie-style since the mid-‘80s, singer-songwriter and all-around artist Juliana Hatfield formed her first band Blake Babies while attending the Berklee College of Music. The trio released four albums before it disbanded in 1992. She then lent her bass talents to the Lemonheads and played on the band’s ’92 hit It’s a Shame About Ray. She went solo later that year, released several records and stockpiled a stash of charted singles including “My Sister,” “Spin the Bottle,” and “Universal Heart-Beat.” Her latest record Lightning Might Strike dropped on December 12 while the third single “Fall Apart” hit shelves—if such things still exist—on November 18.

From the beginning, Hatfield’s creativity has been fueled by myriad challenges including loss, change, and even her own in-built shyness. Lightning Might Strike came heavy on the heels of several: a family illness, the death of her dog, and a city swap. But of all the songs on the record, “Scratchers” was the one that surprised her the most. “I like it because I thought of it as a throwaway,” she recollects. “I remember thinking that it wasn’t very good but I decided to give it a try and see what happened. But it really sprang to life and became a weird little song about scratch tickets, hopes and failures. Often the songs that I think are going to be the most successful turn out to be disappointing and the ones I think are deep-cut nothings turn out to be the best. It’s a reminder that there’s a lot of magic and mysticism in the process; you’re letting in these magical outside forces and it’s a good lesson in humility. You can’t control it all.”

The title Lightning Might Strike was inspired by several things: her mother’s brother being killed by a lightning strike when he was only 16, the idea of fate and perhaps even human fallibility. “That’s a line from ‘Scratchers,’” Hatfield explains. “It’s about buying lottery tickets despite the odds of winning being so unlikely. We need to have hopes, dreams, and fantasies. My mom felt that her brother’s death was his fate so she was able to accept it. I’ve always thought that fate is a powerful force in my life. We can’t control our fates and that’s where the title originates. In the bigger picture, it’s about being grateful for what we have and about finding balance. It’s a reminder to myself not to give up on my dreams but also not to be an idiot and think that I deserve wonderful things. Somewhere in the middle is probably the more realistic thing."

“Most of the best music is inspired by challenging emotions and trying to work through difficulties,” the artist continues. “Making songs is a way of coping. I don’t deal with things well. On an interpersonal level, I’m not a great sharer, I’m not verbal or a communicator so I write about it. That helps me come to terms with things instead of going to a therapist. I also had problems with confidence or shyness when I was younger. I didn’t know how to bond or be myself. Making music was a path to self-expression and to release difficult things. That’s probably true for many artists. It takes a long time to figure out who we are.”

A significant portion of Lightning Might Strike—drums and bass—was recorded remotely, a process that’s a metaphorical roommate that moved in during the COVID lockdown and has never left. “I taught myself to record using my laptop during the pandemic with my ELO covers album [Juliana Hatfield Sings ELO],” Hatfield recalls. “A lot of that was done remotely. Both approaches have their pros and cons. The financial difference is great, given how expensive [pro] studios are. If I record at home, it doesn’t really cost anything. Lately that’s where I’ve done most of my work. I do miss the camaraderie of being in a studio with other people but I also don’t mind being isolated in my house. It’s nice not to have to hear from the peanut gallery when I’m working; I don’t have to have other people’s opinions in my ear. It’s probably good to be in a collaborative situation but I did sit with the drummer [Chris Anzalone] when he did his parts.”

One of her go-to pieces in the studio is the microKORG keyboard with a built-in Mellotron emulator. “I’m addicted to the flute sound and I put it on every album,” Hatfield observes. “There’s a lot of it on Lightning Might Strike. It’s so little, easy to plug in and is transportable. Real Mellotrons are delicate, heavy and big. There’s no way I could get one in my small space but I got to use one at [Cambridge’s] Fort Apache, a studio where I used to work.”

Even authorities don’t know best what’s right for you. I’ve learned to trust my own ideas. But you have to balance that with being open to other people’s ideas and you have to make the decisions.

Her favorite studio memory is of bumping into Lou Reed at N.Y.C.’s The Magic Shop when she recorded 1995’s Only Everything. “It wasn’t like he was LOU REED, the icon,” she reminisces. “He was just this quiet guy who was really nice. It was a cool little interaction.”

Hatfield’s taste for touring has soured in recent years, her tolerance waning with each successive outing. When Music Connection spoke with her the week before Thanksgiving, she had a lone record release show planned at Somerville, MA’s Irish-leaning pub The Burren on December 14, two days after the debut of Lightning Might Strike.

Visit julianahatfield.com