When I was just back from my first year in college, I was staying in the house in Lexington on Hunt Road, and I was just getting things together and rehearsing and playing at the house. We had a big open basement and I had a great little set-up there with guitars, a turntable, and a collection of records I was trying to practice off of—and lift licks from—Paul Butterfield Blues Band and Al Kooperand Mike Bloomfield solos.

So, guitars were a big thing for me, and I had a Fender acoustic and had just bought a beautiful Fender Stratocaster, white and in perfect condition.

My parents had gone away for the weekend and my younger brother invited all his slacker and stoner friends over to drink beer and hang out. They were a real bunch of thugs and dopers and the party got started and I was downstairs when the police showed up at the front door and created quite a mad dash for the doors and exits. Kids came running down the back stairs for the garage door exits, and I got hit from behind with a table leg and was out like a light.

When I came to, the police were everywhere, quite a few items had been stolen from the house… and when I looked over at my little studio, my beautiful 1971 white Strat was gone. I was heartbroken. How could my brother have friends like this and what in the world had he done to these people?

My younger brother vanished, turns out he didn’t know any of these people, and I spent two days cleaning the place up and trying to track down my Strat and the person who had taken it from me.

I tried for years to ask people for leads—try to find the people who were there that night—but I was met with a dead-end at every turn. It was really sad because, as the years wore on, that 1969 Jimi Hendrix Strat had become pretty valuable. But time moves on and as the decades went by, it became a smaller burr under my saddle, but still a pain in my heart, and I learned to live with the sadness and the disappointments of life and various circumstances beyond my control.

“I am sorry for what I did 40 years ago. Please understand that my few years as a lost teenager do not represent the person I am and try to be. I’ve thought about trying to find you and make amends for many years. I’m glad I finally did.

I wish you well. I’m guessing your music career brings you much happiness and I hope that continues for many more years.”

One afternoon as I was driving west through Dallas, heading to Marfa, when I got a text on my phone—nothing new there, but the message was a bit odd: it said, “are you Eric Sommer? Are you Stevie’s older brother?” That was interesting, so when I got it again the next day, I responded and said, “yes, that’s me… what can I do for you?”

“I am the guy who stole your guitar from your basement 40 years ago. I am in a much better place now, and what I did that night has haunted me for all this time. I would like to try and give you your guitar back and ask forgiveness for what I had done so long ago.”

It was a haunting message, and I was pretty taken aback. I said that would be fine, I am glad he called, and it showed his true character. I gave him my address and he said he was a lost, messed-up kid, high on drugs that night… and sold it the next day. He had no idea what happened to it, but he had something that I would like, that was the same brand, and model but a little different year and he will have it re-fretted, set-up, and sent as soon as possible.

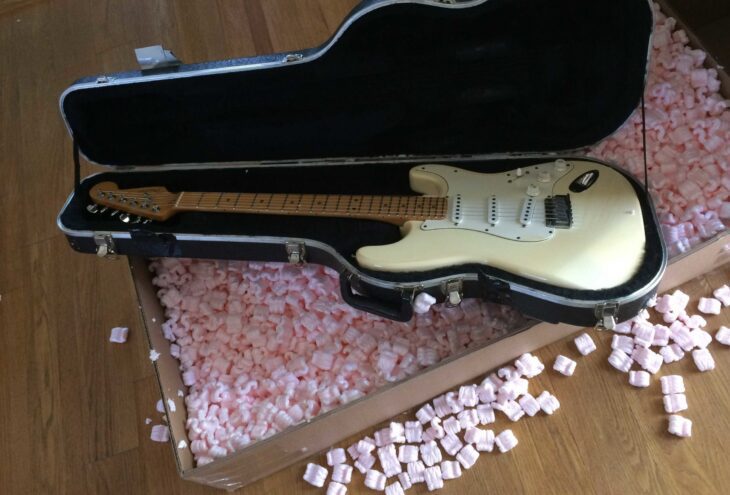

The box arrived a few weeks later, along with the letter enclosed here.

“Here’s my American Standard Strat. I think its model year is 1995. I bought it brand new at Ray Hennig’s store in Austin in 1996. I bought it off Ray himself and he regaled me with stories about how Stevie Ray Vaughan used to hang out in his store every day. Check him out on YouTube.”

I’ve spent most of my life on the road believing guitars are vessels. They carry songs, sweat, rooms, and years. But sometimes they also carry memory—unfinished business vibrating quietly inside the wood. That white Strat didn’t just come back as an instrument; it came back as proof that time doesn’t only take things away. Occasionally, if you’re lucky, it gives something back in a different key.

We don’t get many chances to resolve the long echoes of our younger selves. Fewer still arrive unexpectedly, wrapped in cardboard, with an apology inside. When I play that guitar now, I don’t hear the loss anymore. I hear distance traveled—by both of us. And that feels like music doing what it’s always promised to do: turn noise into meaning, and history into something you can finally lay down.