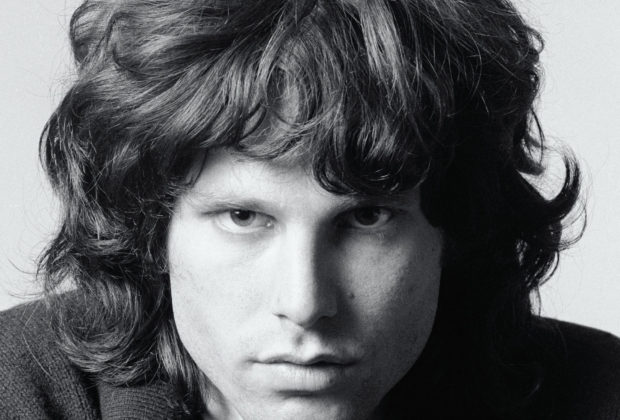

James Douglas Morrison (December 8, 1943 Melbourne, Florida-July 3, 1971 Paris, France)

For nearly half a century I’ve conducted numerous interviews with keyboardist Ray Manzarek, drummer/percussionist John Densmore and guitarist Robby Krieger of the Doors along with intimate associates of the band for published magazine articles since 1974 and in my books this century.

I’ve discussed poet/singer/lyricist Jim Morrison with friends, writers, deejays and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees about the Doors’ enduring catalog, live performances and their legacy.

My focus on the Doors has always been on the recordings and music and the sonic mission of the band, not Morrison’s well-documented legal problems and his 1971 death in Paris coverage.

The below 1974-2021 interviews I’ve done are culled from previously published and never exhibited dialogues coupled with 2021 reflections on the Doors and Jim Morrison.

During June for Record Store Day the Rhino label released the Doors’ Morrison Hotel Sessions, a 2-LP-180-gram black vinyl limited edition of 16,000 numbered copies. Scheduled for fall is a 50th anniversary edition of L.A. Woman.

It’s now 50 years since James Douglas Morrison left the physical world. In June 2021, Harper Design, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, has published The Collected Works Of Jim Morrison-an almost 600-page anthology of his writings.

Executive Editor is Elizabeth Sullivan. Created in collaboration with Morrison’s estate and inspired by a posthumously discovered list entitled “Plan for Book,” this landmark publication is the definitive opus of his creative output—and the book he intended to publish.

An announcement detailed the product.

“A compelling mix of 160 visual components accompanies the text throughout: an abundance of previously unpublished material, including excerpts from his 28privately held notebooks, with numerous examples written in his hand. An array of personal images and commentary on the work by Morrison himself rounds out this highly collectible volume, which includes a foreword by Tom Robbins, introduction and notes by Morrison’s close friend Frank Lisciandro, and a prologue by Morrison’s sister, Anne Morrison Chewning.

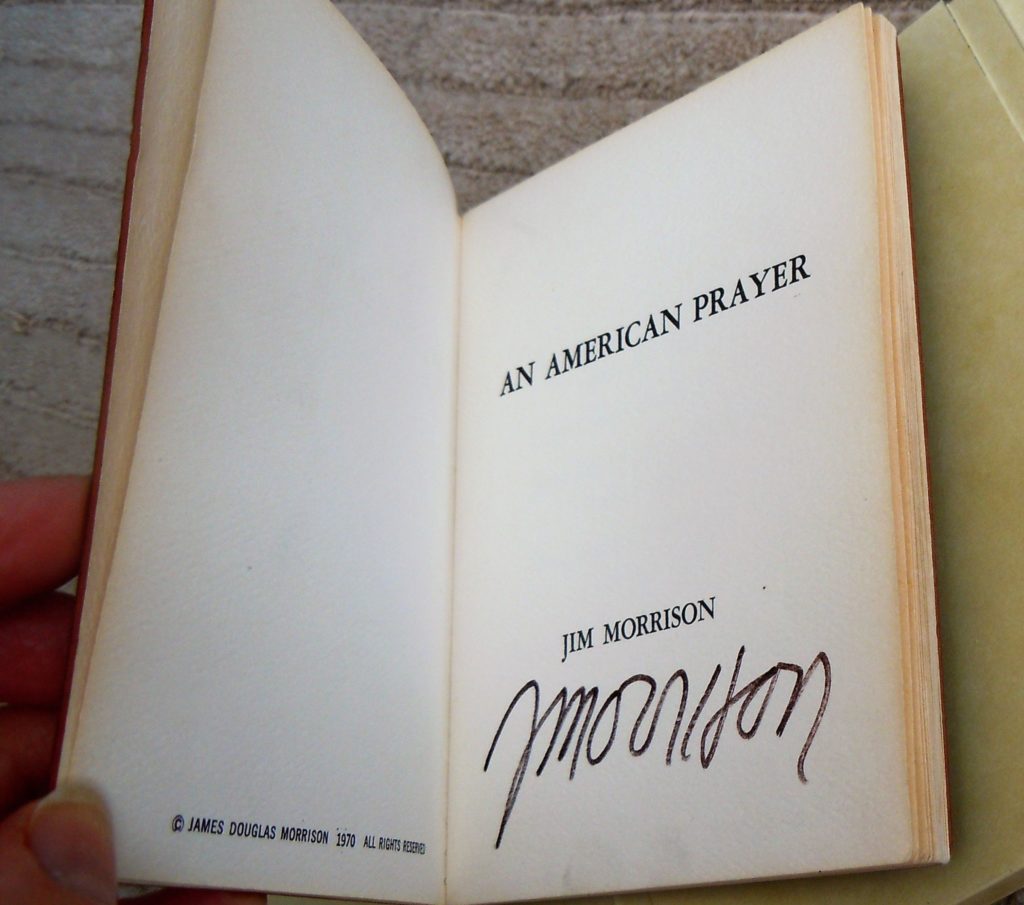

“This collector’s item includes: • Complete self-published poems and writings such as “The New Creatures”; “The Lords: Notes on Vision”; “An American Prayer”; “Ode to LA while thinking of Brian Jones, Deceased” • Published and unpublished song lyrics, with numerous examples in Morrison’s hand• Published and unpublished work and a vast array of notebook writings such as “The Anatomy of Rock,” “The Celebration of the Lizard,” “Dry Water,” “The American Night,” and “Tape Noon” • The Paris notebook, believed to be Morrison’s final journal, reproduced at full reading size, as well as excerpts from the journal he kept during his infamous Miami trial in 1970. “This beautifully produced, oversized hardcover, designed by Michael Bierut and Jonny Sikov of Pentagram, is not only the most comprehensive book of Morrison’s work ever published, it is immersive, giving readers insight to the creative process of and offering access to the musings and observations of an artist whom the poet Michael McClure called ‘one of the finest, clearest spirits of our times.’

“The accompanying audiobook makes available for the first time the full recording of Morrison’s last poetry recording session at the Village Recorder on his twenty-seventh birthday in 1970. A complete transcript of the poems Jim read during the session is in the book as well. ‘This is a historic moment,’ Sullivan says.

“The full digital audio book will not only include Jim’s reading, but readings of his work by other artists, including Patti Smith and Oliver Ray.”

An American Prayer, the ninth and final studio album by the Doors, was initially released November 1978. Seven years after Jim Morrison died, and five years after the rest of the band broke up, Ray Manzarek, Robby Krieger and John Densmore reunited and provided backing tracks over Morrison’s poetry recorded during 1969-1970.”

During early 1966 I was at my friend David Wolfe’s house in Culver City California on Selmarine Drive when Jim Morrison of a new band called the Doors appeared on 90 minute 10:00 pm talk television The Joe Pyne Show on KTTV channel 11. We both remember the confrontational host in a heated argument with Morrison in Pyne’s Beef Box.

I first heard the Doors at Fairfax High School in West Hollywood on Burbank-based AM radio station KBLA during deejay Dave Diamond’s Diamond Mine shift. He constantly spun the acetate of their debut long player in late December 1966 before the official January ’67 album retail release.

The erudite radio broadcaster explained the origin of their name from the title of a book by Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception, derived from a line in William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

I loved Diamond seguing from “Soul Kitchen” to “Twentieth Century Fox.” Some of it sounded like music they had on KGFJ-AM, my R&B channel, and KBCA-FM, the jazz station. “Break on Through (To the Other Side)” reminded me of Ray Charles’ “What’d I Say” from the 1963 Kenny Burrell and Jimmy Smith jazz arrangement recording of his tune on the Verve label.

I purchased The Doors in monaural on the Elektra label that January of 1967 at The Frigate record shop on Crescent Heights and Third Street. I had no idea as a teenager that The Frigate was literally right near the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi-founded Third Street Meditation Center where Ray Manzarek initially met John Densmore and Robby Krieger in 1965, then introducing the duo to his buddy Jim Morrison.

I then saw the Doors in January 1967 on the Casey Kasem-hosted afternoon television show Shebang! In July I caught the Doors on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. I danced occasionally on both Hollywood-based programs 1966-1967.

On April 9, 1967 my cousin Sheila Kubernik telephoned me very late at night. She had just returned from The Cheetah club in Venice and witnessed the Doors in person. Sheila, a Cher-lookalike at the time, was still in a trance, courtesy of Jim Morrison. Shelia later drove my brother Kenny and I to the Valley Music Center for a concert by the Seeds still reminiscing about the Doors.

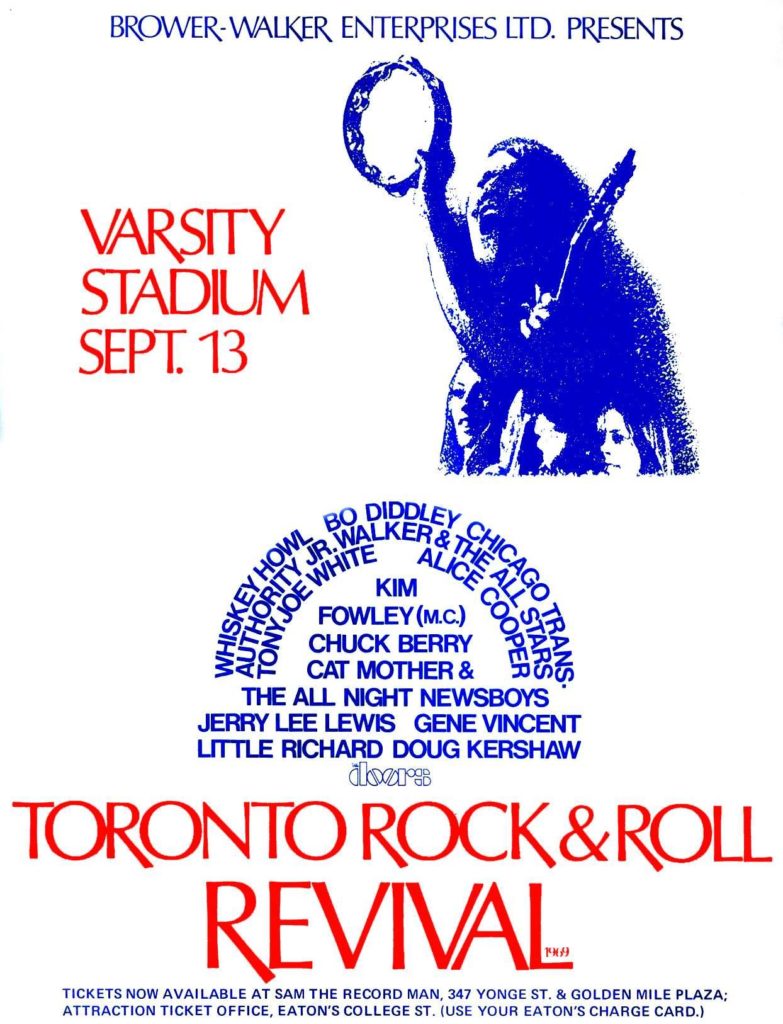

I went to the Doors concert at the Forum in Inglewood, California on December 14, 1968. On the show were Jerry Lee Lewis, Sweetwater, and Tzon Yen Luie, who performed with a Chinese stringed instrument the Pi pa.

I remember as a teenager watching Lewis’ Forum set opening for the Doors where he received a mixed response. I recall The Killer jumping on top of his piano and kissing off the crowd. “For those of you who liked me, God love ya. For the rest of you, I hope you have a heart attack!”

Years later John Densmore told me that the Doors initially wanted Johnny Cash for their Forum booking but the promoter said no because “Cash was a felon.”

In 1972 I coordinated two accredited upper division English and music curriculum courses conducted by Dr. James L. Wheeler, assistant professor in the School of Literature at California State University San Diego. A story in the April 14, 1973 issue of Billboard magazine hailed the department’s academic aim as “the world’s first university level rock studies program.” I placed Jim Morrison’s The Lords & New Creatures on the required book list.

Ray Manzarek heard about our classes and was very complimentary about students seriously studying Jim as a poet, along with the musical works of Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, Jefferson Airplane, the Beatles, Neil Young, and the Doors. Ray and trusted associate Danny Sugerman made arrangements for me to screen the existing print of Morrison’s Feast of Friends movie on campus.

I first met Ray in 1974 and interviewed him at Mercury Records on Hollywood Boulevard. I must have interviewed Manzarek a couple of dozen times over 40 years.

In 1978 Doors advocate Danny Sugerman was a guest on my television program 50/50, broadcast on Z Channel, Public Access and Manhattan Cable promoting his book with Jerry Hopkins No One Here gets Out Alive the first biography of Jim Morrison. Our half hour interview was utilized in the electronic Press Kit by Warner Books advancing Sugerman’s book tour.

Record producer Michael Lloyd, musician/songwriter/producer Todd Rundgren and deejay Murray the K were guests on other episodes. I unearthed from Murray’s archives a video copy of the Doors’ “People Are Strange” from his 1967 Murray The K in New York TV Special and aired it.

All during the eighties, Manzarek played piano and organ on a few albums I produced and spoken word and keyboard collaborations I presented in Santa Monica at McCabe’s Guitar Shop with Michael C Ford, Michael McClure and Allen Ginsberg. Ray lauded my literary work and productions in Westwood on the grounds of UCLA at The Cooperage, Kerckhoff Coffee House and Schoenberg Hall.

In 1990 I served as the project coordinator of The Jack Kerouac Collection box and asked Manzarek, Jerry Garcia and Michael McClure to contribute to the package booklet liner notes.

In July 1995 in East Hollywood at the MET Theatre on Oxford Ave I produced and co-curated with director Darrell Larson a month-long Rock and Roll in Literature series at the venue.

One evening, Manzarek, Densmore and Krieger reunited and played “Peace Frog,” “Love Me Two Times” and “Little Red Rooster” on July 8th. Kirk Silsbee read from Art Pepper’s Straight Life, John Densmore did an entry from his new novel, and Michael Ontkean recited Ode to L.A. by Jim Morrison. Densmore on another night with Paul Lacques, Barbara Williams, Billy Mernit and Andy Kirkun performed the work of Bob Dylan with selections from The Basement Tapes and Tarantula.

Mick Farren, Don Waller, Tim Curry, David Ritz, Roger Steffens, Lewis MacAdams, David Leaf, Bill Pullman, Paul Body, associate producer Daniel Weizmann and I did stage readings on Elvis Presley, the Beatles, Bob Marley, Motown and The Band.

I’m cited in the dedication page of Ray’s autobiography, Light My Fire: My Life with the Doors.

In addition, Manzarek penned the introduction to my 2009 coffee table book, Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon. He graciously joined me for California book event signing events in Oakland and San Francisco.

In 2011, Ray, Doors’ engineer/producer, Bruce Botnick, Elliott Lefko of the AEG/Golden Voice company and I anchored a discussion in the second annual Pollstar Live! Conference, The Doors-An L.A. Legacy, held at the Marriot Hotel at L.A. Live in downtown Los Angeles, California.

In early 2013 Ray emailed me comments for a book my brother Kenneth and I did with photographer Guy Webster, The Photography of Guy Webster Big Shots Rock Legends and Hollywood Icons. Guy took the photos of The Doors LP. John and Robby also provided memories to our Webster text.

My 2014 book Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972 is dedicated to Ray Manzarek who died in 2014.

On January 28, 2018 I attended the memorial tribute and service to Rabbi Isaiah “Shy” Zeldin at the Stephen Wise Temple in the Bel-Air neighborhood of Southern California.

Rabbi Eli Herscher praised Zeldin’s spiritual and visionary leadership in 1964 where he established an open-minded religious and musical community in the region, just a mile from the UCLA campus in Westwood where Manzarek and Morrison were then enrolled as students at the university’s School of Film. From the Bima, Herscher politely encouraged the congregation of mourners “that today, memory is the only agenda.”

I had dinner with Ray Manzarek in 1995 where my only journalistic agenda was specifically asking him about UCLA’s heralded basketball team. Ray mentioned Morrison swam regularly in 1964-65 at a campus pool while he played basketball in the men’s gym around their film studies.

Ray happily confessed that the only down side of being in the Doors during 1966-1971 was when the Bruins’ team were winning NCAA basketball championships he’d miss seeing entire televised games because it conflicted with some of the Doors’ concerts.

“When it was time to perform, I’d only get to see the first half of the basketball game,” Manzarek lamented, “and find out what the score was after the show. ‘What do you mean we have to go on stage? UCLA is on a run…’”

In 1995, Ray and I attended a UCLA basketball game where I introduced him to the legendary UCLA basketball coach John R. Wooden, the icon who helmed 10 titles in 12 years during 1963-1975. I had worked with Wooden in the nineties producing a recording and visited his Encino home on occasion. As we walked back to our seats, Wooden leaned over the guard rail and whispered to me, “Nice to see you music fellows sill tuck in your shirts.”

I watched the UCLA squad on TV win the NCAA crown in 1995 at Lanny Waggoner’s house, along with Ray, Burton Cummings, my brother Ken, and our dad Marshall, who like Manzarek, was born in Chicago. They connected, spending 20 minutes remembering Comiskey Park, and describing Maxwell Street’s tasty hot dogs and polish sandwiches.

Burton shared his remarkable story about encountering Jim Morrison at a party in the Hollywood Hills the first time the Guess Who came to Los Angeles in 1969, later driving tipsy Jim to Ventura Blvd. in Morrison’s Pontiac GTO after they talked about music and writers for hours. Ray grinned, “Hey man, you spent more time with Jim than almost anybody.”

When the basketball match was over, Manzarek exclaimed, “This is like the sixties! The Doors are recording again and the UCLA Bruins won!”

On July 10, 2017 I was at The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s Library & Archives where I was invited to be a guest speaker in their Author Series in Cleveland, Ohio.

Before my appearance, one of the curatorial assistants took me into the private air-conditioned storage locker room not open to the viewing public. “We knew you were coming today and pulled out some specific items we wanted you to see.”

I was handed an envelope containing Jim Morrison’s diploma from UCLA.

Raymond Daniel Manzarek (born Raymond Daniel Manczarek) was born in Chicago, Ill. Ray resided with his family on the South side of Chicago and graduated DePaul University with a B.A. degree in economics. In the early 1960s the Manzarek clan relocated to the South Bay Redondo Beach community in Southern California. It was in Westwood, California in the campus of UCLA in 1964-1965 where Manzarek first met James Douglas Morrison, a transfer student from Florida State University. At the UCLA Film School, Ray earned a master’s degree in Cinematography and Jim a B.S. degree in the Theatre Arts department of the College of Fine Arts. While performing with Ray and the Ravens in the summer of 1965, Manzarek saw Morrison again at Venice Beach and they discussed forming a band together.

In 1965 Ray was introduced to Richard Bock, owner of the monumental World Pacific Records. The label was home to Chet Baker, Les McCann, Barney Kessel, Shelley Manne, Shorty Rogers, Jim Hall, Don Ellis, Joe Pass, Gerry Mulligan, Russ Freeman, Art Pepper and Ravi Shankar. Bock introduced the practice of Transcendental Meditation to Manzarek and gave him two LP’s by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

Rick and the Ravens cut a few promotional singles for World Pacific’s Aura Records, the rock subdivision. On March 26, 1965 the group appeared on the Marvin Miller-hosted Screen Test on KCOP-TV channel 13 at 10 p.m. I tuned in for Eddie Cano, April and Nino, Jackie De Shannon and Cannibal and Head Hunters but faintly recall Rick and the Ravens performing “Henrietta.” Contestants were paired with celebrities to identify old movie clips-a perfect way for a film student to make some extra money.

Bock further touted mantra meditation and spirituality to Ray who then steered him to a 30 person-class inside the Third Street Meditation Center in Los Angeles where he met Densmore and Krieger.

Densmore, a graduate of University High School went to Santa Monica City College and San Fernando Valley State College. Krieger, from Pacific Palisades High School attended U.C. Santa Barbara and then UCLA. Densmore and Krieger had briefly been in a group called the Psychedelic Rangers in 1965.

In early September ’65, Ray Manzarek, his brothers Jim and Rick, Jim Morrison, John Densmore and a bass player named Patricia Sullivan recorded a demo in lieu of another single session date at Bock’s World Pacific studio on Third Street in West Hollywood.

Their acetate results were “Moonlight Drive,” “My Eyes Have Seen You,” “Summer’s Almost Gone,” “Hello, I Love You,” “End of the Night” and “Go Insane.”

In October Ray revamped the Rick and the Ravens lineup, added Robby Krieger and along with Morrison and Densmore, they became the Doors.

Determined band members dropped off the acetate to record labels in town: RCA, Capitol, Liberty, Decca, Dunhill and Warner/Reprise all rejected them.

Eventually it caught the attentive ears of Billy James at Columbia Records, where the Doors had a short-lived stay before finding permanent residence at Elektra Records, the home of the brotherhood 1966 until 1971.

Q: Ray, both Jim Morrison and you went to the UCLA School of Film and students in the motion picture division. You had a class with the French director Jean Renoir.

A: Jim came from Florida, I came from Chicago. We smoked pot together, we talked philosophy together. We had a class with the German director Josef von Sternberg. This was in 1965. Von Sternberg, the great German director of Marlena Dietrich, who did The Blue Angel, Marocco and Shanghi Express.

In my student film Evergreen I used as music the opening strain of ‘The Young Rabbits’ by the Jazz Crusaders. The best 20 UCLA films by students were shown at Royce Hall to the public. And Von Sternberg came up to me after I screened Evergreen and said, ‘Very good Manzarek. Very good.’ One of the greatest moments of my life. So he’s the guy who really kind of gave a real sense of darkness to the Doors, not that we wouldn’t have been there anyway.

But having Von Sternberg seeing the deep psychology of his movies, and the pace at which he paced his films, really influenced Doors’ songs and Doors’ music. The sheer psychological weight of his movies on what we tried to do with our music. The film school is always there. Our song structure was based on the cinema. Loud. Soft. Gentle. Violent. A Doors’ song is again, aural, and aural cinema. We always tried to make pictures in your mind. Your mind ear. You hear pictures with the music itself.

In 1965 we graduated. Jim got his Bachelor’s degree, I got my Master’s degree – and we were hopefully going to do something together. But Jim said he was going to New York City. I thought, ‘Well, that’s it. I’ll never see Jim again.’

Q: The Doors have a song, “Soul Kitchen”, on the soundtrack to Forrest Gump, and piece of five Doors songs appear in that movie. The Doors have always had a relationship with film and movies. I would imagine that the inclusion of “The End” in Apocalypse Now sort of revved up the Doors soundtrack possibilities.

A: The original version of “The End”, with the word “fuck” from the original four-track recording, was mixed in San Francisco for Apocalypse Now. We went to UCLA film school with Francis Ford Coppola. “Break On Through” was in Gardens Of Stone. “Light My Fire” was used in Altered States. “Light My Fire” was used in Taps.

Q: Original Doors recordings were the soundtrack to the film The Doors. “People Are Strange” by Echo and The Bunnymen was in Lost Boys. “Hello, I Love You” was also placed in the Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi movie Neighbors. PBS-TV has utilized a few songs over the years, especially with Vietnam documentaries. “Peace Frog” is heard in The Water Boy. Do you work closely with, or are you involved with, soundtrack or publishing requests to place your songs in films or movies?

A: We are actively involved in saying yes or no is what it amounts to. There is something called a sync license. And it probably started in the 1940’s through the musician’s union or through ASCAP or BMI. But thank God, they have. Because you are not allowed to synchronize picture and sound, picture and song, without an OK from the publisher. And we own our own publishing. Tire companies and gas companies have called for some of our songs, like “Riders On The Storm.” We’ve declined.

Q: Besides the supplemental exposure a movie and subsequent soundtrack collection brings to one of your recordings and the economic gain, what kind of feelings to you get when you hear and see one of your songs taken out of the original context it was written and recorded i

A: Here’s what it is from my prospective. This is my relationship to it. It always becomes the matter of the art. The art is the important thing. What is being communicated to the people who are listening to or watching and listening to the art form. You are taking the Doors songs, and the Doors always tried to make those songs as artistic as they possibly could. It was never a commercial attempt, it was an artistic attempt.

When it works, like in Apocalypse Now, at the beginning, it works like a champ. And it’s absolutely delightful. To sit back in an audience and hear “The End” come on in the beginning of Apocalypse Now, and see the jungle go up in napalm where Jim says, “This is the end,” it’s absolutely thrilling from an artistic standpoint. Film school guys founded The Doors. When he made the music, each song had to have a dramatic structure.

Each song, whether it was two and a half minutes or an epic like “The End” or “When The Music’s Over, you had to have dramatic peaks and valleys., and that’s the sense of drama within the Doors’ songs which comes right from the theatre. The point of art is to blow minds.

Q: Let’s talk about Forrest Gump. Were you aware of the movie being made and that some of your tunes were going to end up on the screen and soundtrack compilation? Excerpts of “Soul Kitchen” are on the soundtrack double-CD. “Break On Through”, “Hello, I Love You”, “People Are Strange”, “Love Her Madly” are in the movie along with “Soul Kitchen”.

A: We got the initial request from the production company that wanted to use five Doors songs in the movie Forrest Gump.. And immediately everyone said, “Time out, what do you mean, five Doors songs? We don’t give five Doors songs to anybody.” Maybe one, or two, if you have a really good movie. Like Francis could have used a couple of more songs if he wanted to. That would have been fine with us, it’s a great film.

Five songs? Forrest Gump? Impossible, man. Then they said, “Look, come down, see the film. We’ll show you a preview of the film, of what we want to do.” We went to see it, and I saw the movie, and I thought the use was so tasty, so tastefully done, and as we used to say in the 60’s, so right on, that we said, “Hey, five songs, man.” It’s just little excerpts and little bits and pieces that are just so skillfully used in the source of the film, we gave them okay to use all five of them.

Robert Zemeckis, the director of the film, did such a wonderful job. And, there’s a sequence where Tom Hanks, Forrest Gump, is playing ping-pong, and becomes a ping-pong expert, and the click-click-click of the Ping-Pong ball against the paddle and the table corresponds with the drumbeats of “Break On Through,” the fast Bossa Nova. So John Densmore is playing the sidestick on his snare and the click-click of the Ping-Pong balls are working counterpuntually to what Densmore is doing. I saw that and said, “Brilliant.” This is good. That’s the use of music and picture. That’s art. So we gave them the okay for all five songs.

Q: I know Jim played tambourine one evening with Rick and the Ravens when you were booked with Sonny & Cher at a high school event, the duo never showed up. Jim said that was “the easiest $25.00 he ever made.” And then he went into a garage rehearsal room with the Doors. Was Jim a natural front man at the Turkey Joint West?

A: No. (laughs). It took a while and later to work it out on stage at The London Fog and Whisky A Go Go. But by God, he sure did scream a lot and sure had a willing injection of energy into rock ‘n’ roll.

Q: Before the Doors inked a record deal in 1966 with Jac Holzman and his Elektra Records, in December of 1965 the Doors had a six month provisional contract with Columbia Records. Billy James, the former publicist for Columbia became the manager of Talent acquisition and Development for Columbia. The label never assigned a producer or even committed to a recording session. Billy James eventually joined Elektra Records in 1966.

A: Without Billy James the Doors would have never made it. On my God! I got my Vox Continental courtesy of Billy James. He heard the original rough Doors’ demo and said, ‘you guys got something. You’re going all the way.’ Jim dropped off the acetate at Columbia. Billy said, ‘Welcome to Columbia Records. Is there anything we can do for you guys?’ And we said, ‘Yeah. You can give us some front money. Do we get paid for signing?’ ‘No, we don’t do that. Do you need any equipment?’ At the time I was playing my brother Jim’s Wurlitzer keyboard. On the demo it was a piano. Columbia had just bought up Vox. Billy offered, ‘You want a Vox Continental Ray?’ ‘Yes!’ Every English group plays one. The Animals, the Dave Clark 5, Manfred Mann. ‘Go out to the Vox Plant in the San Fernando Valley. It’s right across the street from the Budweiser Plant.’ We jump in John’s van and see what we pick up. Robby gets an extra guitar. And we got two amps with 14 inch speakers. We went around to the loading dock and picked up the stuff and got out of there like bandits.

Q: Talk to me about your early encounters with Jim Morrison and his singing voice. I walked with you on Venice Beach recently, you pointed at the sand and said, ‘This is where Jim sang to me in a Chet Baker-like voice. His voice had a softness to it.’ Morrison got better as a singer with the Doors

A: When I first heard Jim sing in Venice I thought he had it. There was no doubt

that he would not have any problems ‘cause the microphone is no problem. Pitch is the problem with a singer. Can you sing in the same key on pitch? And I worked with a lot of singers who can’t do that. Finding the notes. But Morrison had a good sense of pitch. So, if it was in the key of G, he would sing ‘Moonlight Drive’ in the key of G. And he would be there right on pitch. That was the important thing. The rest of it was all acquired expertise in your practice of your instrument.

“Interestingly, on ‘Moonlight Drive’ is that it’s a really a seminal, or a signpost song. It’s the first song Jim Morrison sang to me on the beach. It had been after we graduated UCLA and I ran into him on the beach. ‘What have you been doing?’ ‘I’ve been writing songs.’ ‘Sing me a song.’ ‘I’m shy.’ ‘You’re not shy. Stop it. There’s nobody here, just you and me. I’m not judging your voice. I just want to hear the song.’ Besides, you used to sing with Rick and The Ravens at the Turkey Joint West and did ‘Louie Louie’ until you could not talk.’

Q: Let’s discuss your debut LP The Doors. It was done at Sunset Sound with producer Paul A. Rothchild and engineer Bruce Botnick.

A: Sunset Sound was a very hip recording studio on Sunset Blvd. The Beach Boys had been there. Herb Alpert, Love. It was owned by a trumpet player, (Salvador) Tutti Camarata and he had the Camarata Strings, I believe.

A: It was an excellent recording studio, four tracks. Rothchild and Botnick. Never had met engineer Bruce before. Paul was the producer.

“Rothchild and Botnick are Door number 5 and Door number 6. There’s four Doors in the band and two Doors in the control room. So, they were always there, always twisting the knobs and really on top of it. A couple of high IQ very intelligent guys. We couldn’t have done it without them.

“Paul Rothchild was the guy who had produced The Paul Butterfield Blues Band and also Love, along with Botnick. The two of them did those albums together. So, Robby was a big fan of the Butterfield Blues Band and he was very excited that Paul Rothchild was gonna produce for us. I didn’t know either one of them and not familiar with their work outside of Love. I had heard Paul Butterfield and thought it was good. Chicago blues by Chicago white boys. Being a Chicago white boy myself I could identify with Chicago white boys playing the blues. So it was a great combination of six guys. That first album was basically the four Doors and the two other Doors in the control room making the sound. We made the music. They made the sound. And they did an absolutely brilliant job. And it was a real joy and a great learning experience.

“I had been in a fabulous recording studio before at World Pacific on 3rd Street in L.A. with Rock and The Ravens for Dick Bock. And that’s where we cut The Doors’ demo, along with some Rick and The Ravens songs.

“Rothchild and Botnick were two alchemists with sound. We were the alchemical music makers but they were alchemists with sound-adding a bit of this-a bit of that. Some reverb. Some high end. Let’s hit it at 20k or 10k. Let’s dial in a bit of bass in there. They were making this evil witches brew concoction as we went along. And the sound just got better and better.

Q: And on this album, and subsequent sessions you were joined by a studio bassist who followed and copied your bass lines done on the Fender Rhodes.

A: I was the bass player of the Doors. When it came to recording I played a Fender Rhodes keyboard bass. The instrument was great in person because it had a deep rich sound and moved a lot of air. But in the recording studio it lacked a pluck. It did not have the attack that a bass guitar would have-especially if you played a bass guitar with a pick. You had plenty of attack. So, on some of the songs we brought in an actual bass player, one of the Los Angeles cats, Larry Knechtel. Who played the same bass line that I played on ‘Light My Fire,’ who doubled my bass line. They could then get rid of my bass part and use the nice sound that Larry Knechtel could get. The click and the bottom.

Q: And, in the sound mix the keyboard was treated equally. Not a second thought overdub or hidden below in the collaboration.

A: Well it had to be. We were the Modern Jazz Quartet!

Q: You then start Strange Days LP.

A: Album two is recorded on an eight-track. The first album was four-track. We now had four more tracks. That meant everything that we could do on the first album We would still have four more tracks left over for overdubs. For experimentation. So we experimented in and out of the universe.

I actually played one of the songs backwards. The song was played to me backwards and I had each bar written out with the chord change that went along with it and I started reading the music on the lower right hand side and read right to left across the bottom line. And then jumped to the next line, when I got to the end of the previous line, jumped to the next line up on the right hand side, reading everything backwards, bottom to top, getting closer and closer, finally to the top line and hoping that I end when the song begins. ‘Cause it’s all going along and it’s backwards. I’m following (John) Densmore’s beat on the bass drum not knowing what’s going to happen. And sure enough, I get to the last measure here are four more beats! I stopped and the music stopped. It was a miracle. And everyone went, ‘You did it Ray!’ And I went to the guys and said to them in the control room. And I said, ‘Please, whatever you do, help me here, never let me do his ever again.’ And they collectively said, ‘That’s a deal, Ray.’

Q: You saw the studio becoming a laboratory.

A: Exactly. It was a place where we could really experiment. We could put on our lab tech coats rather than coming in with our ‘Mod’ outfits. It’s almost as if we put on our glasses. I felt like I was in a 1932 German Science Fiction movie, Woman In The Moon, something along that line. Some Fritz Lang. It was like Metropolis and we were wearing those glasses that you wear so you don’t get sparks in your eyes and we had lab coats on. And we were preparing this strange concoction called Strange Days.

Q: You had already had some of the songs for it like ‘Moonlight Drive’ from 1965, ’66, and now in 1967, it’s coming to fruition in the studio. Plus, Jim Morrison’s voice really went further and deeper on the Strange Days expedition.

A: Well, the man had his chops as they say. Jim got his chops together. He had a

thick bull neck resembling a large engorged male organ. (laughs). And by then, he

could sing, man. That throat had opened up and that man was singing.

Q: Water elements are a re-occurring theme in the music of the Doors.

A: Yeah, the water element is always there: the Manzareks living in Redondo Beach, the

Doors in Venice, California.

Always the water. The water is the unconscious, and that’s what the Doors drove into.

That’s where LSD takes you: it takes you into the sun, into the light.

The fire is the sun, our father in the sky. The watery element is our mother, returning

into the womb, diving into the unconscious, swimming around down there to find out

what’s lurking below our regular level of consciousness.

That’s what opening the doors of perception does.

Q: Why do Jim Morrison’s lyrics work so well in recordings and the printed page?

Well, you know, lyrics are poetry. The words were well edited. Jim

was good that way when it came to songs. When you are doing this written poetry you can really stretch out and you can really expand. And, no one so far has done an ‘Ezra Pound’ on Jim Morrison. With his poetry, he’d throw this out, take this line, or two lines, but when it comes to music you gotta be very choosy because you only have a short period of time. Songs in a way, outside of like ‘The End,’ and ‘When The Music’s Over,’ are sort of like haikus. The fit has to be very tight. I saw Jim’s words before he started writing songs. So, when you see his words on the page that’s poetry. I always thought of Jim as a good poet. But when he started writing songs, then everything became verse, chorus, verse chorus. Really tight, and it was a whole other ball game. He put his words into an entirely different context. A musical context. A hit single in a three-minute context. I thought ‘Moonlight Drive’ was brilliant.

Q: As you are hearing Jim’s lyrics to “When The Music’s Over,” late 1967, this is a timeline pre-Earth Day that began in 1970. Those lyrics are detailing ecological concerns and environmental chaos. Psychological territory away from ‘The End’ song. You and the band are a new soundtrack to global warnings and the continual destruction of our planet.

A: I knew Jim was a great poet. There’s no doubt about that. See that’s why we put the band together in the first place. It was going to be poetry together with rock ‘n’ roll. Not like poetry and jazz. Or like it, it was poetry and jazz from the ‘50s, except we were doing poetry and rock ‘n’ roll. And our version of rock ‘n’ roll was whatever you could bring to the table. Robby bring your Flamenco guitar, Robby bring that bottle neck guitar, bring that sitar tuning. John bring your marching drums and your snares and your four on the floor. Ray bring your classical training and your blues training and your jazz training. Jim, bring your Southern gothic poetry, your Arthur Rimbaud poetry. It all works in rock ‘n’ roll. So Jim was a magnificent poet. I loved his poetry and the fact that he was doing ecological poetry. ‘What have they done to the earth?’

Q: Like poet Gary Snyder and his writings and prose on nature.

A: Sure, absolutely man. But don’t forget that’s late 1967, and the potheads were aware. That’s what was so great about marijuana opening the doors of perception along of course with LSD. Marijuana makes you aware that you are on a planet.

“It’s God’s good green earth and you’ve got to take care of God’s good clean earth. The pot heads were the first mass ecological movement. And I hope they continue on and continue it into future because it’s our obligation to save the planet.

“My God, Strange Days, what an album cover. We told the art director from

Elektra Records, Bill Harvey, ‘Make something ‘Fellini-esque.’ And he did that on

his own. That’s all we told him. We saw the photos and said, ‘Bill this is

fabulous. You’ve outdone yourself.’ And Bill said, before he died, ‘That’s the best

album cover I ever did.’

Q: Jim Morrison was the best man at your wedding to Dorothy Fujikawa at Los Angeles City Hall.

A: Jim Morrison and Pamela Courson and the two of us went down to City Hall to get married. And the bridesmaid was Pam and the best man was Jim. And we had our celebratory luncheon on Olvera Street where we had enchiladas and margaritas. And the next night we played the Shrine Auditorium with the Grateful Dead. Psychedelic, man.

Q: Talk to me more about record producer Paul Rothchild.

A: Paul Rothchild was a stone cold intellectual. A fan of Bach. Out of New York City. One of the most intelligent guys I ever met in rock and roll. Great ears.

By the third album, ‘Waiting For The Sun,’ Paul Rothchild was becoming a real Laurel Canyon connoisseur of veteran potent marijuana that was being crossbred by the Northern California growers. All those guys up in Humbolt County. For recording sessions, Rothchild had two types of marijuana: Work dope and also playback dope, which was a little stronger for listening later. One of the benefits of being a known rock ‘n’ roll band

Rothchild had two types of marijuana. Paul had these little vials. One was called ‘work dope’ and the other was ‘playback dope.’ ‘WD’ was not too strong, you could get a little buzz, a little mellow and enter into a proper space and you had your wits about you and had your energy, and could play your instrument. And then after the evening’s recording you could sit back and have something a little bit stronger. This is the listening dope. Light up a joint, have a couple of puffs. Doors weren’t pot heads or dope addicts or anything.

All it took was a couple of tokes and you were stoned. ‘Now let’s hear what we’ve done.’ And we would give it the pot test. The takes that passed the pot test are the ones that stuck around. They are still on the albums. We mixed ‘Your Lost Little Girl’ on some hash.

Jim Morrison rolled the best joints. I rolled one that was flat and crushed, semi-round and loose. It was impossible to smoke a Ray Manzarek joint. That’s why I had to have a pipe I could smoke it on my own.

Morrison had the ability to take a single sheet of rolling paper and he rolled a joint that was absolutely perfect. Like a thin cigarette. ‘How did you do that?’ Ray…It’s one of my God-given talents.’ ‘You are amazing, man.’ The tightest, amazing and cleanest joint, like a half size cigarette. The length of cigarette and the diameter was half the size of a regular cigarette. How he did it I’ll never know but it was always a pleasure to smoke a Jim Morrison joint.

Q: In 1963, you were in the U.S. Army stationed at a Southeast Asia military base in Korat, Thailand. It was there where you tried marijuana for the first time.

A: The first time I smoked pot was back in Thailand. When I was in the Army we lived in these little quanset huts, these little shacks. There was an air base that we were connected with. You would have little house boys from the nearby village in Korat who would shine your shoes, take care of your clothes for you, help clean the barracks. You would pay them a couple a bucks a months and they were more than happy. One day, I asked one of the boys, maybe age 12 or 13, ‘Can you get me ganja?’ And the kid just froze for a second. ‘You smoke ganja?’ ‘Yes. I would like some ganja.’

“What happened was that earlier I had gotten a joint from one of my black brothers. So I said, ‘I will trade you cigarettes for marijuana.’ I exchanged a carton of American cigarettes that cost me around two dollars on the PX base and he brought me some Thai sticks stuffed into a can of Saltine crackers. To him that was like the greatest deal he could have ever imagined. The pot cost him nothing, he cut it off at the bottom of a stalk and put into a foot long can with a lid on it. I swear. You open the can and there is this folded over stalk of marijuana. Now he would normally buy one of those cartons from one of the GI’s for four dollars. I got it for him at two dollars. And he would take that thing and sell it and make like eight to ten dollars on a carton.

“It was a Saturday night, nothing to do, so we decided to smoke this stuff. I had a couple of hits and came on. The first trip was when I realized what the word stoned was. I could not move. I sat there and looked into outer space stoned out of my mind. It wasn’t a giggling thing. It was a profound awakening. ‘Oh my God.’ And every five minutes I would have to stick my tongue back into my mouth. Little by little. Sort of choking and realizing my tongue was all the way out of my mouth and I had to push it back in. I was sitting there like a moron, stoned and just in a complete state of absolute joy. Not giggly or silly, just amazed at the profundity of being alive on planet earth. This went on for four hours while we drank some Cokes and ate pound cake from a nearby snack stand.

Q: The Waiting For The Sun album. Some songs already existed in raw form but

a lot of new material was written for this endeavor.

A: You know it’s time to do a record when you have 10 or 12 songs together. I mean, when we would get together in the rehearsal studio they were polished. They were changed. They were adapted. Somebody, invariably Robby or Jim who would come up with the original idea. But boy, the four of us would get together, change and modify and polish the songs.

Q: “Hello, I Love You” from Waiting For The Sun had been around for

a while.

A: Yes. It was a song Jim wrote on the beach when we used to live down in Venice. Dorothy would go off to work and Jim and I would go off to the beach around the rings on the sand at Muscle Beach and work out around the bars, rings and swings and get ourselves into physical shape. He was gorgeous. Man, he was perfect. He was a guy who had opened the doors of perception and made a blend of the American Indian and the American Cowboy. He was the white Anglo Saxon Protestant. The WASP who had taken on the mantle of the American Indian. He now was no longer a fighter of Indians. He was a lover of American Indians. Like John F. Kennedy, that guy would have been a great President. Pre-alcohol, would have been a great President. The alcohol unfortunately destroyed Jim Morrison.

Q: On The Soft Parade you had Harvey Brooks as well as Doug Lubahn

on bass, saxophonist Curtis Amy and George Bohanan the trombonist.

A: Wasn’t that great. Curtis Amy, who was married to Merry Clayton. Curtis was a

big nationally known jazz horn player who lived in Los Angeles. He takes the solo

on ‘Touch Me.’ It might have been the first time a real jazz saxophone solo went

to number one on pop charts. And, we brought the strings and horn players to

some shows and TV appearances.

It was a great deal of fun for me to bring them on stage.

Q: And by The Soft Parade Jim Morrison started to indulge and really drink.

A: Jimbo came out. They call it the demon rum. There’s a demon in the bottle.

And there’s a demon in that white powder, too. A demon on the blade. You know

what those things do? They open the trap door of the subconscious and allow

some creature to come out. And the alcohol for Jim, a genetic pre-disposition

to alcohol, something came out, man. Some kind of combination.

He went from being the poet to a shooter. Shooter Morrison. I was flabbergasted.

While you can see that Jim Morrison is undergoing a transformation.

Right before our very eyes. And I hoped that this transformation was short

lived. But it wasn’t. ‘This can’t last. This is not Jim.’

“We started experimenting in the studio. I wouldn’t allow anything to get out of

the recording studio without my approval. If I didn’t think it was right it did not go

a record. Nothing happened without my OK. We did some composite vocals. You

do what you have to do. If Jim sings one line great. Fine. Then let’s get the next

line. Let’s get the words, man. Whatever it takes to get the best possible

performance. The Soft Parade’ song is an unusual piece of music. It’s a suite

Q: Then we have Morrison Hotel.

A: Well, we had done out horns and strings experimentation.

We had had a great time. I had a great time.

Critically it was our least acclaimed album. However, it has stood

the test of time and there are many great songs on there. So, you know what?

We’ve done that experimentation. Let’s go back to the blues. Let’s get dark and

funky. Let’s go downtown for the album cover. We went to the Hard Rock Café on

skid row with (photographer) Henry Diltz. And we went to a flophouse called

The Morrison Hotel. Rooms A sign read $2.50 and up. It was definitely supposed o

be a funky album and you can see that on the inside photo and the front and back.

Album covers were always important. We were involved heavily in that process.

You could never just turn it over to the record company. Everything that the Doors

turned out had to be stamped by the Doors. We approve of this.

Q: There’s a song called ‘Waiting For The Sun’ on Morrison Hotel.

A: We loved the title. But the song had not come together earlier. We finally got it

beautiful piece of music. It needed to cook more. Sometimes Doors’ songs came

out of the collective conscious whole. ‘Bam. That’s it.’

Others needed to cook and they needed be worked on.

And ‘Waiting For The Sun’ one of those songs with a great title.

Q: It’s a hard mean album. Morrison’s voice lends itself to this specific material.

A: It was a barrelhouse album and barrelhouse singing. He’s smoking cigarettes.

‘Jesus Christ, Jim. Do you have to smoke cigarettes and drink booze?’ He didn’t

say it but it was like, ‘This is what a blues man does.’ Oh fuck. That’s right.

Q: How could Jim Morrison with his Dionysian demeanor write and suggest instruction or guidance lyrically in that song, “Keep your eyes on the road your hands upon the wheel,” when most of the time he certainly didn’t operate or drive a car like this himself?

A: Well that was the better Angel. That’s Jim Morrison. Not Jimbo. Jimbo was the guy who took Jim to Paris and said, “let’s go and die in Paris.’ We’re going to have a death in Paris. Like Thomas Mann’s novella Death In Paris. That was Jimbo.

Q: In addition, the album brings us as into the water and film noir aspect of

Los Angeles. Water is a principal theme explored.

“Ship of Fools.” The “River of Sadness” cited in “Peace Frog,” and

the salvation of the ocean and the destination charted in “Land Ho!”

A: Water, ships. It clicks big time. The water images and that beach down in

Venice. And that ocean side. ‘Moonlight Drive’ again. And the water

always entered into Morrison’s life. And where does his life expire? In the water

in the bathtub in Paris. From the amniotic fluid of his birth to the bathtub in Paris. .

“The album was definitely blues, ‘Raymond Chandler.’ Downtown

Los Angeles. Dalton Trumbo. ‘John Fante.’ ‘City of Night’ John Rechy.

Q: Then there is the tune “Peace Frog.” In 1995 you told me for Goldmine magazine, “Blood in the streets in the town of Chicago” is obviously about the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. It was written after the young people rioted against the war, in Vietnam.”

A: Those are great lines. Morrison goes further to say, ‘Blood is the rose of mysterious union/blood will be born in the birth of a nation.’ So it’s the idea that blood is the cleansing property, and from blood will come the healing and the enlightenment of the nation. America is what Jim is singing about. ‘Birth of a Nation.’ Another cinematic reference.

Q: In 2007 for Goldmine magazine we talked again about Doors’ catalog utilized in movies and soundtracks. The film school influence is obvious again, especially on ‘L’America’ on Morrison Hotel.

A: It was written for the director Michaelangelo Antonioni for his film Zabreskie Point. And we played it for him at the rehearsal studio and backed him up against the wall with the volume. We played it the way we normally play and too loud for this elderly Italian gentleman. I could see him pressed up against the door trying to get out of the place. We finish the song, he slides the door open and steps outside and it was almost like he was saying, ‘Goodbye boys. Goodbye Hollywood.’ And then he goes with Pink Floyd. It was all too much for him. He just couldn’t do it.

Q: Just before the album L.A. Woman formally began, producer Paul A. Rothchild leaves the project.

A: Yes. He did a great service to us. We played the songs in the studio so Paul could hear what the songs were. First at the rehearsal studio and then over to Elektra. I think we went back to Sunset Sound, too. We were bored. He was bored. We played badly. And Paul said, ‘you know what guys? There’s nothing here I can do. I’m done. You’re are gonna have to do it yourselves.’ And he walked out the door. We looked at each other and said, ‘Shit. Bummer.’ And Bruce (Botnick) said, ‘Hey, I’ll do it! I’ll be the producer.’ John (Densmore) said, ‘We’ll co-produce with you.’ Bruce said, ‘That’s a deal. Let’s all do it together.’ And then Jim said, ‘Can we record at our rehearsal studio?’ And we all said, ‘Hey, we play great at our rehearsal studio. Let’s do it..Can it be done?’ And Bruce said, ‘Of course I can do it there. I’ll set the board up and a studio upstairs. You guys record downstairs. That’s where we make the album and it will be virtually live. ‘Yea!’ And we got excited like that Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland ‘Let’s put on a show!’

Q: Jerry Scheff plays bass on L.A. Woman.

A: Botnick brings in a guy who is going to be playing with Elvis Presley. ‘I got Elvis Preesley’s bass player.’ ‘Shit, man.’ He came in. A very cool guy who is playing with Elvis Presley.

Q: And, you and Jim just earlier had watched the “Elvis Presley ‘68 Comeback Special on television. I wrote the liner notes in 2008 for the CD reissue. Elvis is wearing leather on that program. And I believe Jim had his leather pants made on Sunset Blvd. in 1967 or in ’68.

A: Yes. We watched it. Elvis puts on his Morrison outfit. (laughs). He had seen Morrison. He knew what he was doing. Imitating Jim.

Q: L.A. Woman is a logical step from Morrison Hotel.

A: I think it’s the same Doors but a continual growth, continual evolution of The Doors. Continual revolution of The Doors.

Q: The title track “L.A. Woman” embodies movement, freedom, lust and dust.

A: ‘L.A. Woman’ is just a fast L.A. kick arse freeway driving song in the key of A with barely any chord changes at all. And it just goes. It’s like Neal Cassady, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg heading from L.A. up to Bakersfield on the 5 Freeway. Let’s go, man.

Q: The haunting “Riders On The Storm.” In 1995 you ran down the song to me commenting on that highway and freeway chase depicted. “The storm is an unresolved psyche. We are moving into the Jungian collective unconscious. And those motivations in the collective unconscious are the same in 1976, 1968, 1969 as they are in 1994, 1995. There are needs that we all have on the human planet, and we must satisfy those needs and come to grips with the darkness and the interior of the human psyche.”

A: It’s the final classic, man. Interestingly, Robby and Jim come in and were working on ‘Riders On The Storm.’ And then they start to play it and it sounded like ‘An old cow poke riding out one dark and misty day.’ It was like ‘Ghost Riders in The Sky.’ No. We don’t do anything like ‘Ghost Riders In The Sky’ as much as I like it by Vaughn Monroe. And Jim likes it. What’s next? A version of Frankie Laine’s ‘Mule Train?’ Doors don’t do that. Let’s make this hip. The idea is good. We’re going to go out on the desert. ‘There’s a killer on the road.’ This has got to be dark, strange and moody. Let me see what I can do here. It was like ‘Light My Fire.’ It just came to me. I got it. The bass line. It became this dark, moody Sunset Strip 1948 jazz joint.

Q: And, only Morrison could inject a Hollywood movie studio system reference in the lyric ‘an actor out on loan.’

A: Yeah. How ‘bout that, man.

Q: Jim’s poetry album An American Prayer.

A: I don't think anybody was actually ready for the record. It was the first full-length rock 'n 'roll poetry record and it was 15 years ahead of its time. I think people are going to be surprised, because they think of Jim Morrison as this screaming, hell-bent-for-leather maniac, a wild lizard king. When they hear him read his poetry they're finally gonna know the sensitive Jim Morrison I knew when I first met him. You can hear the vulnerability.”

Q: Every Doors concert was unique. Some specific songs in the set but lots

of improv and no set order.

A: The concerts were an extension of the audio document. It was not yin and yang.

One was an extension of the other. There were improvisations in the recording

studio but within their soloing sections. And quite frankly, I never knew what

I was going to play. I knew the chord changes. I didn’t know how I was going

to structure my A minor 7h chord. That would vary from take to take.

It would always be an A minor 7th and in the groove. So there was improvisation

in the studio but here was major improvisation live.

“The whole Doors’ organ sound, what makes that work, that’s my whole Slavic upbringing. That’s being a ‘Polish Pianist.’ That’s that dark Slavic Stravinsky, Chopin, that great mournful Bartok type thing. Dark, mournful Slavic soul married so perfectly with the Carson McCullers American Florida southern gothic words ‘Tennessee Williams’ poetry, that the two of us went ‘Crunch!’ and the whole thing came right together perfectly. Playing with Jim, Robby and John was falling off a log. Writing those songs and inventing things.

“The Doors…Each song and album has its own place. I still play the albums and

can live the emotion. A lot of beautiful times went down. I think of going to UCLA, meeting Jim, meeting Dorothy Fujikawa who’s now my wife and a lot of great times.

“That was such a fecund time as Jim said, in that year we had a great visitation of energy. That year with the Doors lasted from 1965-1971. We were just composing fools. So that was the easiest thing I’ve ever done.

Q: Who is buying Doors albums these days? It took a long time after his death for the band to become hip again.

A: There was a period right through the '70s when everything was either country rock or glitter rock, and you couldn't hear The Doors anywhere. Then Danny Sugerman and I said, "Wait a minute, we're not going to allow this to disappear..." Little by little, we just started beating the drum for Jim and the band. That culminated in The Best Of The Doors, which we put together for people who knew of The Doors but didn't know what to buy.

Jim was a big influence on Patti Smith. Punk rockers loved the fact that his songs and poetry were so dark and ominous.

John Densmore.

Q: You caught a lot of jazz in Hollywood in the very early sixties

A: I saw Coltrane many times. I noticed with Elvin Jones and John Coltrane there was communication. So, I thought, ‘I’m gonna keep the beat. That’s our job as drummers. But, I’m gonna try and talk to Jim during the music.’ Like, ‘When the Music’s Over.’ “What have they done to the earth….” That’s Elvin [Jones]. I knew I wasn’t playing jazz.

“I saw Sonny Payne with Count Basie at The Crescendo. Chico Hamilton at the Light House club. There was this ride cymbal riff that Chico did on a song. The ride cymbal on ‘The End’ once I get to the kit I’m playing the tambourine. It’s Chico Hamilton. That’s where it came from. Chico was direct, and going into the bridge on ‘Wild Child.’ That’s the press roll from Art Blakeley. That was direct from the records on Pacific Jazz and World Pacific.

Q: Tell me about 1965 and The Transcendental Meditation Center in Los Angeles.

A: Well, Robby and I went because LSD was legal and we were quite interested in our nervous systems, and knew we had to do this TM thing slowly. We go over there and I meet this little guy, Maharishi, and the ‘Love Vibe’ is very palpable. This is 30 people in a room. Then, a year or two later, I read that the Beatles are onto TM and our little secret is being spread worldwide. Great. I still meditate. The whole Eastern Indian thing, Ravi Shankar, via George Harrison and the Beatles saturated everything with paisley bedspreads sound wise. ‘The End’ was a raga tune.

“Ray had a previous relationship with World Pacific Records in 1965 when he was on the label with Rick and the Ravens and recorded for Dick Bock who owned the label, and released Ravi Shankar albums in the US.

“We got a couple hours of free studio time at World Pacific recording studios, and that’s when we got to make a demo in 1965. On the way into the studio Ravi Shankar is leaving with Alla Rakha, my idol, who I didn’t know was going to be my idol yet, was on the way out with these little tabla drums, which I soon find out by studying at the Kinnara School of Indian Music, are the most sophisticated drums in the world. I’m in awe of them. It’s the East! And, I’m just a surfer. Not literally, but from West LA. The very first TM class was with Clint Eastwood and Paul Horn the year before me. Paul later was in India with the Beatles.

“I don’t know if you know this story. Jim didn’t meditate, Robby and I went and Ray was there. That’s where we met. One time Jim came and he wanted to look into Maharishi’s eyes…and Jim later said, ‘Well, he’s got something. I’m not gonna meditate but he’s got something.’ This was the first class in the country. We were two years ahead of the Beatles, thank you (laughs).

I find it interesting that across the pond, the fab four were exploring the same thing as us... and there was no internet back then. Both groups were experimenting with then legal LSD, then drifted towards a less shattering route on the nervous system -- Maharishi and meditation.

“So maybe, 1966, 1967, I was noticing in the traditional Indian ragas you gotta wait for your climax. It’s not a quickie, you know. So that was the influence. Frankly, TM is the reason the Doors are together. TM. You could buy instant nirvana for $35.00 then. Now it’s thousands of dollars. And TM glued together myself, Ray, Robby and Jim.

“Robby and I went to Ravi Shankar’s Kinnara School of Indian Music. When you’re students at the Kinnara School of Music, you get to sit on stage with the master at UCLA’s Royce Hall. Later Robby and I go see Ravi play at the Hollywood Bowl, and George is on stage. Ravi didn’t teach at the school, but he’d drop in and give a little lecture on Sublimating Your Sexual Drive Into Your Instrument. Harrison was doing it in England. Later, George Harrison came to one of our recording sessions for The Soft Parade. You hear the Indian thing in techno stuff now. That came in and it was deep and it’s still around. We need the East.

Q: Laurel Canyon during 1966, ’67.

A: I shared a house with Robby on Lookout. I had cruised Laurel Canyon many times previously over the years looking for a place because it was the coolest spot in Hollywood. We knew that Frank Zappa was there having jam sessions that we went, me and Robby. Frank didn’t get that. That was interesting. He didn’t smoke or drink. He was wild enough to not need it. (laughs). He sort of wanted to produce us. Terry Melcher wanted to produce us. We were the house band at the Whisky A Go Go and everyone was trying to figure out what to do with ‘Light My Fire,’ because it was so long.

Robby and I are in Laurel Canyon in 1965, ’66, and a block from Appian Way at the top where you can see the whole city. Where later I bought a house where Carole King lived and the actor I heard James Coburn was just down the street playing his gongs. Jim and Pamela were in the Canyon later. Well, Jim in 1965 was in Venice and didn’t have a telephone. He was on a rooftop. So, Robby and I thought if we could find a place with him nearby it would help us track him down. So then we moved to Briar, which was a stucco two story and Jim was next door. Ray is not in Laurel Canyon. Arthur Lee was down the road a little off Briar.

When the Doors were at the London Fog. We used to take breaks and I’d walk down and stand next to Mario at the Whisky and listen to Love. And Elmer Valentine the other owner of the Whisky, he was such a great guy. And Elmer loved Jim so much even with all of his antics. Elmer loved music and was very cool. Mario, too. Phil fired us for some of the words in ‘The End,’ but Elmer hung on and never lost faith in us. Sweet guy. So, I’d be standing with Mario, ‘Damn, I can play as good as that drummer.’ ‘Shit…I wish I was in that band…’

Then Ronnie Haran, who was the booker at the Whisky caught us on our last night, when we were fired, there was a fight and they blamed it on us, and so she booked us into the Whisky as the house band. We were good and Jim was attractive. Ronnie and Jim ended up together later for a while. Then, when we were the house band, Arthur told Jac Holzman of Elektra Records to check us out which was very generous. Arthur was very generous but very introverted. Frankly,

smoked so much herb that he was paranoid but very creative and generous. Mamas & Papas’ Denny Doherty was around.

I lived on Utica before I had my own house on Appian Way where I’d see Carole King on walks and was very friendly. She was married to Charlie Larkey. They were working with Lou Adler then and his Ode Records label, and Robby and I produced an album called The Comfortable Chair for Ode Records. I knew John Locke the keyboardist of Spirit, they were on Ode, and John lived in Laurel Canyon. I knew him from 1964, ’65 from a club in Westwood, Ledbetter’s, the Rising Sons would play, David Crosby, John Locke used to jam there. I saw Spirit’s drummer, Ed Cassidy, play there a lot. And all this was before the Doors. I saw John a little bit in Laurel Canyon. I liked Spirit very much. I knew Bob Hite of Canned Heat. The Spirit members later were Topanga Canyon based. Topanga is sort of the western extension of Laurel Canyon. I jammed with Lowell George of Little Feat at his place. Just me and him. It was fun.

When I lived on Utica, 1967, Neil Young was my next door neighbor. The landlord was Keiki. She had this rambling ‘Hobbit’ like place with two or three guest houses and Neil was in one and I was in the other. I can remember when Neil said, ‘come on over. I want to play you something.’ And he plays me ‘Expecting To Fly…’ And so then I remember, ‘I bought a house in Topanga.’ He had just quit the Buffalo Springfield and was moving out. And he said, ‘Well, I got forty grand, that’s what I got out of the Buffalo Springfield and bought this house. I’m out of here,’ and bought this house. And I have very fond memories of those times with him.

Q: Talk to me about 1967.

A: On May 20, 1967 on the same day we played the Whisky A Go-Go in Hollywood, and the next night as well where we played with either the Byrds or Buffalo Springfield. “Break On Through” had got to number 11 when we played the Whisky, partially due to our phone calls. People were coming to the Whisky, like Sonny & Cher’s management. Greene & Stone, the Turtles, Sunshine Company, the White Whale label people.

It was Greene & Stone [managers of Sonny & Cher and Buffalo Springfield] who made the initial suggestion to cut down “Light My Fire” for radio since it was 6:50. Their suggestion was to put one half of the song on one side of a 45 and rest on the flip side. That was cute.

Subsequently, Robby and I went over to a local DJ’s apartment, Dave Diamond from KBLA-AM, and he said it was a hit but mentioned “you have to edit this down (for airplay).” So, we pressed (producer) Paul Rothchild, and he just whacked at it, and all of us felt the cut was kinda brutal. But then, we became the darlings of the FM radio stations who played the long version. And, that jump started the whole FM underground “We’re cooler” scene. Which was very cool.

“Light My Fire” hit number one in July, our album went gold in September, and we did more gigs in Las Vegas, and the Cheetah on the Santa Monica Pier in Venice.

Jim had an astounding baritone. Un-schooled. Never got nodes like Grace Slick and had to have surgery. God, if you don’t have that bottom… It was luck. It was fate. He never sang before I saw him in the garage. It was kinda squeaky in the early days. He just was afraid to open up. How audacious. “OK. I’ve never sung and I’m gonna be the lead singer of a rock band.”

I had to work harder on the tempo because Ray’s left hand was the bass. And when he took a solo he’d get excited and speed up. “Hold it back. Hold it back.” But, without a separate guy doing bass line runs and grooves there are holes. “OK. I’m going in.” Sometimes I didn’t do anything. That was my territory between the beats.

During band rehearsals or just before we recorded, mainly I heard Jim’s words live and by himself in the garage, or Ray would hand me a slip of paper and they were pulsating rhythms of words. Because Jim was a poet they were edited. Like, “Break On Through” was so percussive. When we were recording and locked in, I was in it. We were just so in it. We were lost. Playing live there were big sections on “The End” or “When The Music’s Over” when we would vamp, and Jim would throw in anything. And then, “Oh yeah? I’ll throw that back at you. Check this out.”

“With the Doors I had to work harder on the tempo because Ray’s left hand was the bass. And when he took a solo he’d get excited and speed up. ‘Hold it back. Hold it back.’ But, without a separate guy doing bass line runs and grooves there are holes. ‘OK. I’m going in.’ Sometimes I didn’t do anything. That was my territory between the beats.

“You know, we wrote the first two Doors albums before we made any records. Jim had just written ‘People are Strange’ on a matchbook. He then did ‘Love Street’ about the Laurel Canyon store and living next door to it. I know it’s kind of light to the dark Doors, but melody is paramount to me. I’m a drummer. Jim was great. This was early. Young, energetic, curious, a smart guy who knew nothing about music and was real interested in how it all worked. He was cool.

A: Sunset Sound had a real echo chamber like the famous echo chamber at Capitol and it had a pocket that was fat. Just a warm fat echo chamber. You can’t buy that kind of shit. First of all when I went into Sunset Sound in the very beginning I had no clue what a good drum sound was. And I couldn’t believe you had to change the sound and kind of muffle it. Which Rothchild taught me. I loved Paul Rothchild but he got so perfectionist. He was tough but taught us so much. And mid-period, Waiting For The Son and The Soft Parade, he had me doing a s drum sound to tap on each drum and I’d have to do it for a fuckin’ hour. And I was exhausted. We did a 100 takes for ‘The Unknown Soldier.’

Elektra was a good studio. My thing was that I taped my wallet to my snare drum. And then we’d go to eat and I’d leave my wallet and I didn’t have to pay for drinks. (laughs). Not on purpose. Like in the 1950’s drummers used to do that before mufflers.

By the time we started working with Bruce Botnick at the Doors’ Workshop and in 15-20 minutes, ‘Great. Let’s go. You’ve made a lot of records and you know what a good drum sound is. I don’t have to flog you like Paul used to do.’ We did L.A. Woman there and it was more live. And Jim was in the bathroom which was our vocal booth. We did no more than a couple of takes on everything. Just pure passion and no perfection. Strip it down to the bare raw roots.

“The concept of L.A. Woman was like the first punk album. Just a few takes, go for the feeling, fuck the mistakes. During the sessions I told Ray that Miles's engineer said there was a trumpet mistake on the opening of ‘So What’ on Miles Davis Live at Carnegie Hall, and Miles said, ‘leave it in... It feels good!’"

Robby Krieger:

Q: The Strange Days LP

A: The last song we did on the Strange Days album was ‘When the Music’s Over.’ We had been doing it live a lot, and it was fun because it was different every night, kind of like ‘The End.’ Lots of improvising.

So the night before we were to record, the phone rings about 4 am. I knew who it was. Jim says, ‘Robby, Pam and I took too much acid, man, you gotta come over. You gotta help us.’ I got out of bed and drove over there, fearing the worst. They were like harmless babies, not on a bummer, but more just bored, I immediately knew what to do. When on acid, always seek nature! They wanted me to take some but I refused, I said, ‘Let’s go across the street to Griffith Park. It’ll be great.’ ‘Yeah, yeah,’ they were excited. As they started out the door I said, ‘Shouldn’t you get dressed first?’ They agreed and out we went. They were freaking out, having a great time, so I figured they were okay.

“I said, ‘Jim, remember we’re recording tomorrow.’ ‘I’ll be there.’ “Of course, he wasn’t. Probably asleep we assumed. What to do? Ray said, ‘let’s do the track, and leave spaces where Jim does his thing.’ We decided it was worth a try, so we laid it down, trying to imagine where Jim would come in, and other such improvisations that were different every time we played it. Finally Jim shows up eight hours late, pretending to have forgotten the 2 p.m. start…He got it in one take. Amazing!”

Q: In 1968 the Doors headlined at the Hollywood Bowl.

A: As far as the Hollywood Bowl: It was amazing to be asked to play the bowl. Growing up in Los Angeles and playing the bowl must be like playing baseball in New York and playing Yankee stadium. We were really psyched! So much so that we actually rehearsed! [first time ever just for a gig] and we decided to capture the whole thing on film [and 8 track tape] normally, we would just wing it at gigs...we might discuss what to start with, 2 or three songs and then just go with the flow. Looking back, the rehearsal may have been a mistake. I think it may have made things a bit unspontaneous, not a good thing when the Doors were supposed to be so wild and free, never knowing what might happen next.....also the fact that Jim was peaking on acid was not in line with such a tightly controlled show,,, check out the Granada film, Doors Are Open...that was more of a spontaneous Doors show...luckily, the footage from the Hollywood Bowl looks great and we fixed up the missing songs, so we now have the complete show.

Q: The Doors began recording The Soft Parade in November 1968 and completed it in July 1969.

A: When we started The Soft Parade it was after the Beatles’ Sergeant Peppers.

The Soft Parade was recorded in West Hollywood at Elektra Sound Records on La Cienega Blvd produced by Paul Rothchild who brought in arranger Paul Harris to do the string and horn overdubs on The Soft Parade.

“I never liked the idea myself of strings and horns. It was an experiment. But once we decided to do it we did it. In fact we knew going in that the arrangements were made for the songs were actually tailored to have strings and horns. I would work with Paul Harris ‘cause I knew very little about orchestration. I would give him ideas for a horn line here and there and hope for the best. But he really did most of the work.

Q: Paul A. Rothchild produced albums by The Paul Butterfield Blues Band and Love.

A: Paul Rothchild was great. He was just what we needed, a very strong personality and real smart which Jim looked up to. And he knew a lot about recording, you know, which we knew nothing about. There are very few guys that Jim would look up to actually and the same with us. He would make us do 50 takes. Bruce Botnick our engineer for all the albums and the producer of L.A. Woman is a little bit overlooked. He is a perfectionist. So is Paul. Bruce is the guy who actually turned the knobs and you can’t argue with the sound he got. He was very young but had produced the Supremes and a lot of stuff.

“It was a blast to have Curtis Amy in the studio. That was the most fun part. You got to meet all these great musicians and hang out. They were our heroes. Like on ‘Touch Me,’ Curtis took the solo. That was the first time that happened. It served the song. That was another example of egos not getting in the way for the sake of the song. Leroy Vinegar was on our Waiting For The Son album. In fact he played on ‘Spanish Caravan,’ which was pretty silly ‘cause it wasn’t his type of forte.

The only reason we wanted a stand up bassist was that it was right for the sound and Leroy was a good reader, and it was a written part. Probably any guy could have done it. Doug Lubahn and Harvey Brooks were the bass players on The Soft Parade. Leroy was a bit taken back when he saw what we wanted to do. ‘This isn’t really my thing.’ ‘Come on, Leroy, you can do it.’ (laughs). On stage we didn’t have a bass player just the three musicians. Ray covered it. There were a couple of other groups who did that, the Seeds and Lonnie Mack. I loved Lonnie. He played on ‘Roadhouse Blues.’

Q: How was the material on The Soft Parade developed and constructed?

A: I came in with some songs and it was not like I had not done that before like ‘Love Me, Two Times.’ It was more like coming up with stuff on my own. Jim was getting more and more hard to work with as far as songwriting goes. It wasn’t the Jim who was writing ‘Your Lost Little Girl.’

Q: Let’s discuss the songs on the disc. “Tell All The People.”

A: I had never written anything political and I heard this song by Leadbelly called ‘Fannin Street’ about a street in New Orleans. And he had this line in there, ‘Follow me down.’ I really liked that line.

Q: Then the hit “‘Touch Me.”

A: It was originally called ‘Hit Me, Babe’ and Jim thought people might take it literally on that. (laughs).

Q: “Runnin’ Blue.”

A: I remember seeing Otis at the Whisky. I was standing right in front of the stage for the whole show. I never heard of Otis Redding before and I was amazed at the energy that he created on stage. I would stand right there on the dance floor, stage right.

“I wrote the song 'Runnin' Blue' but when Jim [Morrison] started to sing it, he just came up with that Otis dead gone part right on the spot. Seemed to fit pretty good. So we left it in. I guess the horn parts reminded him of Otis.

Jim and I had a telepathic relationship. It was a perfect combo. That’s how you make a great group. You have three, four or five guys who come together and have that perfect intuitive relationship and stuff comes out.

When we did the first Doors’ album Jim was totally un-experienced in the studio as far as recording his vocals. He had a year with his voice playing live every night. He had never done anything in the studio. And I think by the time The Soft Parade came around his voice had matured a lot as far as low notes and range. Stuff like that. I don’t think he could have sung ‘Touch Me’ nearly as good if that was on our first album.

Q: “Do It.”

A: It started off with a lick that I had and we needed words for it. And I didn’t have anything. And so we would go to Jim’s poetry book. A lot of times that’s what happened. Like with ‘Peace Frog.’

That was different. It was a crazy little song that I had and when I sang it to the guys they really liked how I sang it. ‘You sound a little like Bob Dylan. Maybe you should sing that song. And then Jim added the part about Otis Redding. That’s an example on how Jim would make my songs better. We had an ethic that we wanted to make the song better. Jim was amazing in that way. Possibly the least ego-bound songwriter I have ever worked with, no question. As far as, ‘Hey…That’s my line…’ It wasn’t like that at all. He was always open to discussion and for things I told him to sing. He wasn’t really a musician but usually what would happen is that he would come up with something better.

Q: “Wishful Sinful.”

A: It’s definitely one of my favorites on the album. The orchestration is really good. I love the chords and stuff I came up with on that song. I wish I knew how I did it. (laughs).

Q: “Wild Child.”

A: It’s one of my favorites because it’s live. That one didn’t need strings or horns. The title song ‘The Soft Parade’ was quite a work. It was actually three songs in one.

“We didn’t tour the The Soft Parade album. We only did it twice. It was another step for the Doors to try something different. The reason I didn’t like it was that I felt we were kind of doing the album for somebody else. But I definitely like how it came out, you know. A couple of years later we tried re-mixing some stuff without the strings and horns but it didn’t quite work. We had actually tailored the arrangements to horns and strings and to put that out again would be a lot of work, or alter the arrangements.

Bruce Botnick Engineer/Producer

Los Angeles native Bruce Botnick, is a sound engineer and record producer. At age 18 he talked his way into a job at Liberty Records in Hollywood where he subsequently recorded Bobby Vee, Johnny Burnette, Jackie DeShannon, Leon Russell, David Gates and with arranger Jack Nitzsche.

Botnick then moved to Sunset Sound, hired as a mixer initially to do children’s albums for Disney.

Then the Doors walked in off the street into the fabled Sunset Sound facility with their producer, Paul A. Rothchild, an A&R signing courtesy of Elektra Records’ founder and owner, Jac Holzman.

Botnick is acclaimed for engineering the entire Doors’ recording catalogue as well as engineering Love’s first two albums. He also produced their epic Forever Changes LP. in 1967. He co-produced the Doors’ L.A. Woman.

Bruce was at the dials at several epic rock ‘n’ roll special moments: “Here Today” from Brian Wilson’s Pet Sounds, Buffalo Springfield’s “Blue Bird” and “Expecting To Fly,” and a credit as an assistant engineer to Glyn Johns on the “Gimme Shelter” session on the Rolling Stones’ Let It Bleed.