An inspirational new book, 88 MORE Ways Music Can Change Your Life, by Vincent James & Joann Pierdomenico, features an installment written by Simon Tam, frontman of The Slants, based on his band’s experience performing at a maximum-security prison.

“Assumptions”

“Assumptions”

In the Summer of 2011, I was invited to bring our band The Slants to the Oregon State Penitentiary. The Johnny Cash fan inside me was so excited, I immediately began planning an outfit that would be all black. That excitement overshadowed everything else, not thinking twice about the waivers we were required to sign in order to perform.

The waivers were filled with “hostage disclaimers” to ensure we wouldn’t sue if we got shanked, killed or maimed while there. It never crossed my mind, that the idea of sending an all-Asian American band into a prison with one of the largest populations of white supremacists, could be a dangerous one. I mean, I signed similar forms just to perform at high schools.

Things began to change as we arrived and were handed bright orange vests to wear over our clothes. Our singer, Aron, asked if we could take them off mid-concert since our own suits could get quite warm and it was a very hot day. “Sure,” the guard said, “but, if something happens out there, those vests let us know who not to shoot.” “Yo, can I get two of them vests?,” I asked, “I want a backup in case I lose mine.”

“As they got closer, I could see the words emblazoned across the chest of the man in front: WHITE POWER.”

We continued through security with significant precautions taken at every step. There were bars and armed guards everywhere. The clanging of the doors would echo loudly every time one would open or shut.

Obviously, the place was designed for containment, not comfort. The only thing I knew about prisons, was what I learned from books, TV and movies. But this was before the hit show Orange is the New Black began its run so, at the time, I didn’t see the prison industrial complex as a way to perpetuate white supremacy. I only thought about the kinds of people that were sent to a maximum-security prison: drug dealers, murderers, rapists. Was this a good idea?

Eventually, we stepped onto a large field surrounded by tall concrete walls. They called it “The Big Yard.” I looked up at the sentry towers, placed strategically around us, with searchlights and mounts for weapons. There was a large running track with a grassy field in the center. At the end, was a small stage with a thin line of plastic police tape stretched across the front. I read the words POLICE LINE DO NOT CROSS. This flimsy plastic tape was the only thing that was going to separate us from nearly two thousand convicted criminals.

“Um…I don’t know if they follow those kinds of instructions,” I told the guard. “I mean, that’s kind of why they’re in here, right? They can’t follow instructions.” He told me not to worry. They had a plan. He said if anything happened, we should drop everything and run through the opening in the chain link fence behind the stage. “Our guys will be stationed there, so once you’re through, we can secure the fence.” “Ok, let me get this straight,” I said. “If something happens, run. You’ll be on the safe side and, if we make it through, you’ll lock the fence behind us.” Did they get this plan from The Walking Dead?

As we started our set, a small crowd began to assemble in the front, while the rest continued to walk around the yard––getting the only hour of outdoor time they’d have for the day. As we continued playing, more inmates began gathering closer to the stage. As we launched into our cover of “Paint it Black,” hundreds of prisoners jumped and cheered. It was incredible, watching a sea of orange and blue ripple in front of us. Our little 45-minute set turned into a two-hour marathon of music.

At the end of the concert, I was standing near the edge of the police tape (on the safe side, of course), when a group of shirtless white men began walking towards me. As they got closer, I could see the words emblazoned across the chest of the man in front: WHITE POWER. He and his companions were completely covered in swastikas and white pride tattoos. The man in front walked up to me, blocking out the sun in the process. He seemed nervous as he handed me a piece of paper with a small, sharp pencil.

He asked me for an autograph. I didn’t know what to do. I was completely frozen. But, then, he said four words that cut right through me: “It’s for my daughter.” I turned over the paper. It was a makeshift flyer for our show in the prison. He wanted to tell her that he had met the band. My band. “I know what you must be thinking,” he said. “I’ve made a lot of mistakes in my life and they’re ones that I don’t want my little girl to make.” He wanted to show her that he could learn, that he could change his heart and mind, even if he couldn’t change what was stained into his skin.

This was one of the most powerful moments in my life. I went in with all kinds of assumptions, but that all changed with that one brief conversation. For the rest of our time there, I walked around on the other side of the police tape, listening to the men behind bars tell their stories. The music we shared that day truly helped to open them up. The other band members had similar exchanges as well.

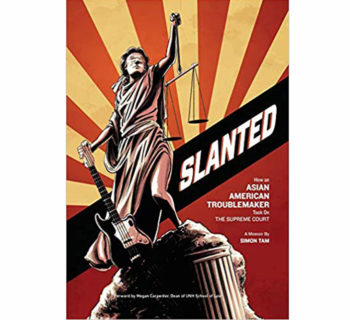

I started The Slants because I wanted to change people’s assumptions about Asian Americans. Assumptions can be powerful. However, this deliberate act of claiming an identity was something the government considered to be disparaging, initially denying us the trademark to our band name - something that I fought and won, at the United States Supreme Court.

The government thought they were protecting the public from harm but, instead, they were erecting walls designed to discourage people from mobilizing for social justice by using language to re-appropriate ideas. They used walls to divide us, both within our own communities, as well as outside of them, pitting us against other marginalized groups. They weren’t protecting us, they were trying to keep us complacent. They didn't stop to think that art, like glass, can provide crucial social mirrors and serve as a window into what is possible.

Against all odds, those walls came down. But, it all began with a name––and music––worth fighting for.

Simon Tam – The Slants

Cincinnati, Ohio – USA

TheSlants.com / SimonTam.org

Photo by Grudnick

“Assumptions” appears in a new book, 88 MORE Ways Music Can Change Your Life by Vincent James & Joann Pierdomenico.