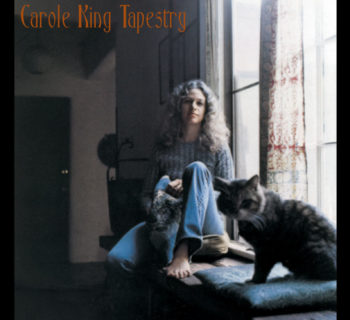

March 2020 is the 50th anniversary of Carole King’s Laurel Canyon-based solo debut album Writer, setting the foundation for the nascent singer/songwriter genre of the seventies. It paved the way for King’s 1971 follow up, the landmark Tapestry that has sold over 24 million copies.

Tapestry, from singer/songwriter and pianist King, produced by Ode Records label owner Lou Adler, with engineer Hank Cicalo at A&M Studios in Hollywood, spent 15 weeks at #1. At the 14th annual Grammy Awards ceremonies it garnered Album of the Year, Best Pop Vocal Performance (Female) Record of the Year, “It’s Too Late;” and Song of the Year, “You’ve Got a Friend” by James Taylor, the first female to win the “grand slam.”

In 2008, Tapestry was re-issued with a second CD of live performances on the Epic/Ode/Legacy record label, a division of Sony BMG Music Entertainment.

The Tapestry long player arrived in early spring 1971 on A&M/Ode Records with little fanfare and modest expectations. It now holds an exalted place this century in the pantheon of pop music; a triumph of master craftsmanship married to a feminine sensibility that transformed both its audience and the marketplace. If Jane Austen came back as a gutsy, guileful, Brooklyn girl, with a knack for a lyrical and musical hook, she’d be Carole King.

In 1995 musical artists re-recorded the original tracks for Tapestry Revisited: A Tribute to Carole King,” and in 2003 a second salute, A New Tapestry-Carole King Tribute was minted.

In 2003, as yet another milestone of its importance, Tapestry was one of 50 recordings selected by the Library of Congress and placed in the National Recording review.

In a 2008 Epic/Ode/Legacy Records communication Carole King commented about Tapestry.

"I feel honored that Tapestry has made a difference in small ways and large ways in people's lives around the world. It's been a major part of my life, too," she adds. "As a songwriter, I'm so happy that the songs have held up for all of these years.”

Tunes from Tapestry were spotlighted in the award-winning Beautiful The Carole King Musical, based on the book by Douglas McGrath which debuted in 2013 at the Curran Theater in San Francisco, Ca. A 2020 UK stage show tour opened February 3rd and continues to August 20th.

By 1969 King had evolved from the Brill Building cubicle world of New York City writing on demand to writing for herself not the charts. And that played neatly into the current unfolding singer-songwriter community.

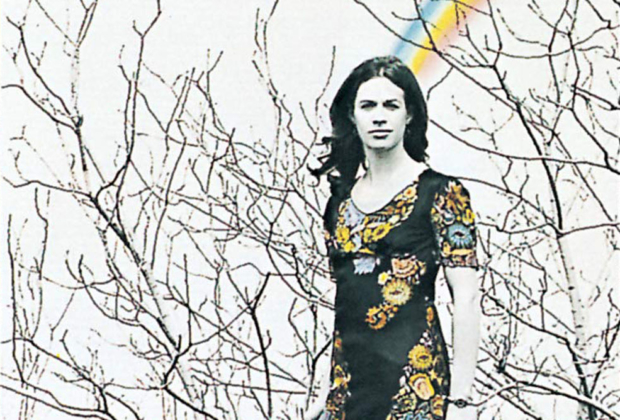

Carole in front of her home on Appian Way, taken 2/13/71. Photos by Jim McCrary, courtesy of Lou Adler Archives.

Long before Writer and Tapestry shipped to retail outlets, King had an earlier New York City journey at the Brill Building, located in Manhattan 1619 Broadway on 49th Street, the songwriting community near Tin Pan Alley. It housed music publishers and record label offices where hit records songs were conceived and written.

Some of these tunesmiths were staff writers at Aldon Music, a publishing company founded in 1958 by industry veteran Al Nevins, and aspiring music entrepreneur Don Kirshner, based at 1650 Broadway at 51st Street.

During 2020 the Netflix streaming service is producing a documentary on the Brill Building’s songwriters and composers of the last century.

This historic melodic world was lensed at length in 2001 by director Morgan Neville in his stellar Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music,” which examined the songwriting teams of Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller, Carole King, Gerry Goffin, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil.

Director Neville in 2014 won an Oscar for Best Documentary for his 20 Feet From Stardom.

If Mike Stoller and Jerry Leiber had only written “Hound Dog” for Big Mama Thornton, along with “Kansas City” and “Stand by Me,” they would already deserve their place in The Songwriters’ Hall Of Fame and The Rock and Roll Hall Of Fame, both of which have inducted them. Leiber penned the lyrics and Stoller composed the music.

The dynamic duo also gave us “Jailhouse Rock”, “(You’re So Square) Baby, I Don’t Care,” “Trouble,” “Treat Me Nice,” “Little Egypt,” “Love Me” and “Loving You” by Elvis Presley, “Ruby Baby,” “Dance With Me, “ “There Goes My Baby,” and “On Broadway” for The Drifters, “Only In America” (Jay And The Americans), “Saved” (LaVern Baker), “Drip Drop” by Dion, “I (Who Have Nothing) (Ben E. King), “Love Potion #9” by The Clovers, “I’m A Woman” and “Is That All There Is?” that Peggy Lee hit the charts with.

“We had probably the first independent production and record company,” Stoller told me in a 1999 interview. “We were the first I’m told, by guys at Atlantic Records. We learned from watching Johnny Otis. Johnny was a major talent scout. We learned a lot from watching guys like Maxwell Davis, who was wonderful, an unsung hero.”

“After a while we learned styles of songs that led to styles of arrangements,” disclosed Leiber in the same ’99 conversation. “And it was shorthand. Like with the Robins’ ‘Framed,’ the multiple narrative voice. I had heard before. Jimmy Ricks and the Ravens. He’d come in with a bass line…I must say, I really didn’t think about the songs I was writing. They were natural sort of evolution of a state of mind. I’d be walking down the street and start singing a line. I didn’t think of it. It would happen. The only time I started actively thinking was when I started to edit the work and make it fit better. We formed Spark Records later with Lester Sill and put out The Robins.”

“Back in the early 50’s, like ’52 or ’53 or whatever, those disc jockeys were banning records and saying rock ‘n’ roll is over,” recollected Mike.

“In fact, around ’53, or maybe 1954, Billboard magazine, which was on newsprint at the time, came out in the year-end issue saying, ‘rock & roll is over.’ And I remember Lester Sill saying, ‘No way, man. This music is here. This is going to last. This is going to be here for a long, long time.’ He was right.

“Jerry and I moved to New York later in the 1950’s so we kind of separated our partnership with Lester. In terms of the music business, Lester was our dad. The business now is a different game. The business became a different game. Lester was such a sweet man, such a human being. And he kept up with all the changes in the business. “

Leiber and Stoller were later partners in Red Bird Records, started in 1964 with George Goldner but by 1966 had sold out their interests.

“Here’s what happened,” summarized Mike. “After a while at Red Bird, numerous things led us to just give it up and turn it over to George Goldner, who had helped to build it because he knew how to sell records. We knew nothing about that. We only knew how to make ‘em. And one of the things was that we were bored. And around this time I said to Jerry, ‘If we get one more hit act, we’re gonna be stuck here for another ten years.’ We had The Ad Libs, Shangri-La’s, Dixie Cups, and Alvin Robinson. What happened around that time, a few acts came to see us who were waiting outside and never got to see us. One of those acts was the Young Rascals.”

The influence of the Brill Building-based Leiber and Stoller informed songs and recordings of the seventies and eighties.

“Jerry Lieber was a great inspiration and was vital to the start of my songwriting career,” acknowledged Leon Huff, half of the songwriting and production team of Gamble and Huff.

“I also had the fortunate opportunity to play piano on many Leiber and Stoller recording sessions as a musician in the early days,” Huff stated. “When I had dreams of being a producer, I met Leiber and Stoller in the Brill Building when they called me to play on ‘Boy From New York City.’ I was so nervous, but when I started grooving, that's when I really settled down, because Jerry and Mike cut some really groovy records. That was a great time for me as a studio musician. I’ll never forget Leiber and Stoller because they helped me get the knack of the studios.”

“I have been a fan of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller for years,” praised Chris Darrow.

“Their ability to be white and write for the black sensibility was phenomenal. Only a handful of writers have had as much luck with that approach. Johnny Mercer, Hoagy Carmichael, Goffin and King and Mann and Weil were all able to bridge that gap but it was Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller who really changed the heat of rock ‘n’ roll. Goffin and King knew how to write for black people. That was one of the many things I can give them credit for. They understood the black mentality more than just about anybody at the time. That was one of the things Phil Spector had, too.

“When Leiber and Stoller entered into the writing world of early rock and roll, the singing group was one of the most popular ways that a song was presented on record. It was mostly coming from the Ink Spots model. Usually there was a lead singer, with other singers who basically sang back-up harmonies. Jerry Leiber wrote lyrics for the whole group. Thus, his ensembles like the Robins and the Coasters created characters within the group structure and gave the group a dialogue, as well as a song to sing. There was a call and response consciousness that certainly came from early Negro gospel singing. But there was also a more sophisticated, storytelling interaction, where the various characters took on the roles of actors within the story.

“It became more like a musical on Broadway, than a song from the rock and roll idiom. That’s what set their partnership apart from other songwriters and producers. Like Duke Ellington, who wrote for a set of musical personalities, so did Leiber and Stoller. The Coasters were a cast of singing actors playing little vignettes of everyday life.

“Part of the bond that musician Chester Crill and I have had over the years is our affection for Leiber and Stoller. Kaleidoscope recorded ‘I’m A Hog for You Baby’ for Beacon From Mars, but it wasn’t used at the last minute. On each of our two reunion records we covered a Leiber and Stoller tune. We did ‘Little Egypt’ on When Scopes Collide and Down in Mexico on Greetings from Kartoonistan (We Aint Dead Yet).”

It was in 1957 when pianist Burt Bacharach and lyricist Hal David met at the Brill Building which led to a songwriting partnership. Marty Robbins recorded “The Story of My Life,” which hit number on the US Country Chart in 1957. Perry Como subsequently did “Magic Moments.”

It was Jerry Butler in 1962, after leaving the Impressions, who not only waxed B&D’s "Make It Easy on Yourself” but requested Bacharach to arrange and supervise the session.

The Bacharach/David duo wrote over a hundred songs for vocalist Dionne Warwick. By 1965 her Scepter Records label had moved to 254 West 54th Street.

“On Dionne’s first record, I had her on take four,” Burt Bacharach enthused to me in our 2000 interview. “Maybe the difference now from what it used to be is that I know I’m going to be O.K. at 95 percent. You can make yourself crazy going for 100 percent. It’s not about what you get, but what you’re gonna get as a result. Something is gonna be at fault in the record. The guitar player played great but you don’t do it all at the same time. Played great on the one take, but the drummer made a mistake, or didn’t play as good, or didn’t go to the ride cymbal when you hoped he would. Then the balance shifts and you didn’t get the performance on the next take. It’s about compromising. Get as close to...

“I learned something from Don Was. He said, ‘It’s not so important that somebody makes a mistake, if the track is there and the song feels good. If the song is there and the vocal performance is there, that’s it.’

“I started making my own records out of self-defense, to protect myself. Because I think (years ago) I ruined some good songs, because I trusted some of the A&R people. I thought they really had to be good, or they wouldn’t have that job. If I had a three bar phrase, then that really worked as a three bar phrase. It’s like let’s take a song like ‘Wives and Lovers.’ Thank God nobody suggested it in the A&R department, but if somebody had said, ‘We’ll get so-and-so to record it, it will be a single, it’ll go in the movie... but you’ve got to put it in 4/4...’”

I asked Burt about his philosophy of arrangements, especially his use of orchestration on those irresistible sides Warwick did for Sceptor Records.

“I’m very conscious of too much strings on records. It’s an invasion of some territory that I’m very allergic to now. But then our intent was not to be crowded in the composition, or crowded in what was gonna be jammed in on the color, the orchestration, things that would be too busy behind.

“First of all, you’ve got to have a lead going in. So, when you know you have a situation that plays, then you can take the strings - and I overwrote the strings a little bit, I didn’t realize I overwrote until I heard ‘em and then I realized, ‘...hey, let them play five bars and let’s bail. Let’s bring ‘em out for that sweep down, and then, right on the modulation...’ And, you know... It’s like you have a great smile but you can’t use it all the time. Drop it in.”

It wasn’t until 2017 that I fully understood the effect the Brill Building had on The Band’s Robbie Robertson. It’s chronicled in his autobiography Testimony.

In a 2017 interview I asked Robbie about his time at the Brill Building with Ronnie Hawkins and meeting Morris Levy of Roulette Records as well as encountering the songwriting teams Leiber and Stoller, Pomus and Shuman, music publisher Aaron Schroeder and Henry Glover.

“One of the things that I really took away from that was Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman or Leiber and Stoller, or Otis Blackwell, and a thing I had to cut out [from Testimony] with Titus Turner, who was an incredible character,” recalled Robertson.

“Anyway, one of the things I really got from them, because the obvious thing was that they tapped into something that felt good. But it had to feel good. The song could be about anything but it had to feel good. And I was like. ‘Wow…’ It would be one of the guys sitting at the piano playing. ‘Let me think of something. What about this?’ And they would start to play something. I was studying. I didn’t know what the song was about but it feels good. So I just thought coming in that door, coming in the back door of something, that when you start this thing if it doesn’t feel good then stop right now. ‘Ah-ha. That’s something.’

“I thought who would think in their wildest imagination that Tin Pan Alley was a real place. The Brill Building, and then Donnie Kirshner’s thing. All of it was actually in a place you could go. And the doors were golden when you walked in. And inside there in all these rooms were people who wrote songs and sent them out to the whole wide world,” marveled Robertson.

“I had such a respect and a connection feeling for these people. And I knew Doc and Mort all of their lives. Doc and Mort remained friends. And I recorded with John Hammond, Jr. on an album that Leiber and Stoller produced. I was friends with Jerry and Mike so to say none of that rubbed off on me just wouldn’t be true.

“I wasn’t the lead singer in The Band. I don’t know if the Brill Building influence was that specific on arrangements and voices but I did try and soak up as much as I possibly could from the guys, so to say none of that rubbed off on me just wouldn’t be true. And it was stuff that I don’t know that if you grasp it on the surface but in a way of seeing the way these guys could adapt to these different artists. And they could write something and then cast it. Or, someone could say, ‘we need this. We’re coming to you.’ And they could write for that. And I thought that was a special gift. And I was doing that in The Band.

“I thought my job was in this was what they were doing too. My job was to say, ‘I’m going to write a song that Richard Manuel could sing the hell out of. I know what to do with his instrument.’ And so the answer is, in some subliminal way, absolutely yes.

“Then, the other door was Bob Dylan who it wasn’t about that. It was about emotion and and energy, but it was really about saying something. It wasn’t about ‘these words could be anything.’ No. No. It was specific. So to me it was rebelling in a beautiful way against this other thing.”

In a 2000 interview with Al Kooper, keyboardist/singer/songwriter/producer and founder of Blood, Sweat & Tears, I asked Al about the Brill Building.

Kooper started his illustrious career in 1957 playing guitar as a member of the Royal Teens who charted with “Short Shorts.” Kooper at the time was teaching at the Berklee College of Music in Boston, Massachusetts.

“One thing I fight is the major revision of my life: Which is that they call it the Brill Building Sound and it never took place in the Brill Building,” explained educator Kooper.

“The Brill Building was always the Brill Building at 1619 Broadway. And it died about 1957. It was huge before that, the Frank Sinatra crowd. It had frosted glass doors, a beautiful, well-constructed building. And then, around 1958, ’59, 1650 Broadway got refinished, and they had black doors and cheaper rents. And everybody went there. There was another building, too, at 1697 Broadway, the building where the Ed Sullivan Theater is. And there were people in there too, but mostly R&B people. And 98 per cent of what they call the Brill Building Sound was done at 1650 Broadway,” Kooper underscored.

“You ask any person that writes about the Brill Building Sound, with the exception of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Burt Bacharach, Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, who were actually in the Brill Building. But here is who wasn’t in the Brill Building: Gerry Goffin and Carole King, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, Neil Sedaka and Howie Greenfield, Tony Orlando, Chuck Jackson, and Dionne Warwick. Bell Tone Records was there, Bobby Lewis and the Jive Five. All this music came out of 1650 Broadway and it was the young people’s place. The Brill Building was for old people.

“Music publisher Lee Silvers [who discovered Herb Alpert and Bobby Hart] was in 1650 Broadway. That’s where I got started. In his office! I became the guitarist for the Royal Teens. He signed me. Bob Gaudio (Four Seasons) and I were all underage. When I met Bob Gaudio he was 16 and I was 14.

“But I’m telling you this specific Brill Building history because it’s the bane of my existence. None of that music, with the exception of the people I mentioned, came from the Brill Building,” stressed Al.

And then there is Carole King.

Born Carole Klein, on February 9, 1942, in Brooklyn, New York, she started learning piano at the age of four, and formed her first band, the vocal quartet the Co-Sines, while in high school at New York’s High School Of Performing Arts, and graduated in 1958.

An avid devotee of Leiber and Stoller, she became a fixture at exciting DJ Alan Freed's local rock 'n' roll shows. While attending Queens College, she met budding songwriters Paul Simon and Neil Sedaka as well as Gerry Goffin, with whom she forged a writing partnership and became her future husband.

King and Goffin inked with music publishers Al Nevins and Don Kirshner's Aldon Music. Her debut single, "The Right Girl" was released on ABC-Paramount Records label in May 1958.

Lou Adler first met Carole King in 1961, when he helmed the Sunset Blvd. West Coast office for Aldon Music (later Screen Gems-Columbia Music) when King and Gerry Goffin were staff writers.

From 1960-1963 Aldon had 36 Top 10 records. Adler was responsible for a Top Ten single in 1960, "Crying In The Rain" (a Goffin-King song) by the Everly Brothers, for whom he produced several sides. He also participated in the release of unretouched demos on Aldon’s Dimension label that became hits, including Carole King’s "It Might As Well Rain Until September," "The Locomotion" by Little Eva, "Chains" by The Cookies, and Freddy Scott’s "Hey Girl."

While he was at Aldon, Adler also supervised the production of a string of hits by Jan and Dean that included "Surf City," "Honolulu Lulu" (which he co-wrote), "Drag City," "Dead Man’ Curve," and "The Little Old Lady From Pasadena."

When Aldon sold out to Columbia Pictures Music, Adler became VP of Columbia Pictures Music. He then left to form his own company, Dunhill Productions, which came to be distributed by Liberty Records.

Born in 1933 and hailing from the Boyle Heights section of East Los Angeles, Adler wasn’t planning to enter show business when he started writing songs with friend Herb Alpert. The first four songs they did together were recorded by artists, Sam Cooke, Cowboy Copas, and Sam Buetra from Louie Primas band. Adler and Alpert did a demo of a tune and took it to Bob Keane at Keane Records who offered the duo A&R jobs working with producer Bumps Blackwell.

Adler lived for a while in 1957 with Cooke in Hollywood at the Knickerbocker Hotel. He also resided with Sam in an apartment on Saint Andrews Place in Los Angeles where George McCurn, Lou Rawls and Bumps Blackwell hung out.

In 1959 Sam, Adler and Herb Alpert wrote “(What a) Wonderful World,” a big hit single for Cooke in 1960, later covered by Herman’s Hermits. Adler toured with Cooke as a road manager and attended Sam’s sessions at RCA studios.

“Sam taught me a language on how to speak with musicians, not only verbal but sign language as far as where to go musically,” Adler told me in a 2008 interview for my book Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon. He penned the Afterword, too. From 1958-1960 Adler lived in Laurel Canyon on Lookout Mountain Drive.

“Sam taught me where the drummer would go and when to layout. That was a language I had to learn and also the communication between producer and engineer. I had no musical or recording experience, so between Bumps and Sam is where I learned.”

Adler saw Cooke every Christmas and on their birthdays. Sam, along with the Everly Brothers played at Adler’s June, 1964 wedding to actress/singer Shelley Fabares.

On December 11, 1964, Sam Cooke was shot to death at a motel in downtown Los Angeles.

“Sam is never talked about as a human being,” Adler emphasized. “He’s mentioned as the great soul singer that he was and the instrument that he had, and the fact that everybody from Otis Redding to Jackie Wilson emulated him, followed him. He was just a great human being, a great guy, a great buddy with a wonderful sense of humor…”

Adler’s business acumen would then give us Johnny Rivers, the Mamas and Papas, Spirit, Merry Clayton, and Carole King, as well as the comedy of Cheech and Chong.

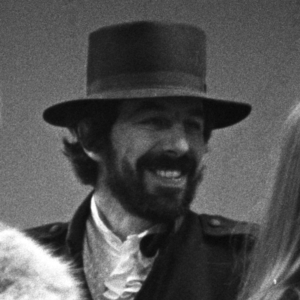

Lou Adler. Photo by Henry Diltz.

Adler, along with John Phillips of the Mamas and Papas forever altered world culture and music in 1967 with the Monterey International Pop Festival. It not only helped bring prominence to Jimi Hendrix, the Who, Janis Joplin and Otis Redding, but popularized a whole new generation of rock ‘n’ roll recording artists who were now here to play and stay.

On April 9, 1967 Paul McCartney flew in from Denver, Colorado, to Los Angeles in a Lear Jet owned by Frank Sinatra. On arrival Paul visits the Bel-Air mansion of John and Michelle Phillips of the Mamas and Papas, a pad above Sunset Blvd. formerly owned by actress Jeanette MacDonald. An aristocracy has paired the hymnists from the international pop underground along with Mama Cass Elliot and record producer Lou Adler. Paul plays guitar and strums and sings “On Top Of Old Smokey”.

That night McCartney is quickly invited to join the advisory Board of Directors, which is planning the Monterey International Pop Festival. Adler and Phillips had just formally taken over the planning of the non-profit event, now scheduled in just two months.

“The motivation came that night at John and Michelle’s with Cass, Paul McCartney, myself and a couple of others; our conversation went to rock 'n' roll as an art form, like jazz. John and I were both aware of the Jazz at the Philharmonic recordings. Someone said, ‘They aren't taking rock 'n' roll musicians seriously.’ Rock 'n' roll was always viewed as a fad that would be over by the summer…but now it was more than just music, it was a lifestyle.

“McCartney’s first recommendation simultaneously along with Andrew Loog Oldham that same day was to book the Jimi Hendrix Experience since they were tearing up England at the time. We looked at Paul beyond an act. Beyond somebody that was singing on stage, as a composer. He was somebody not writing just hits, but great songs. Like ‘Michelle.’

“At John and Michelle’s home McCartney watched cartoons on the television set, improvising a score for what was on the screen.

“Paul never came to one of our recording sessions, but (George) Harrison came by a couple of times. You’re fans of everybody’s records. And once again getting back to Monterey, that’s what brought those people together…that they had been fans of everyone in the other groups. And got a chance to cross and ask those questions like ‘How did you get that sound on that record’?”

“I’d met Lou Adler in Santa Monica California at The TAMI Show in late ' 64,” ruminated Andrew Loog Oldham in a 2007 dinner interview we had. Author and now university lecturer Oldham managed and produced the Rolling Stones’ during 1963-1967.

“He was managing the hosts, Jan & Dean and I was there with the Rolling Stones. We became fast friends. About a year later I was in LA recording the Stones at RCA; Lou asked me to come down to his Dunhill records office on South Beverly Drive. In his office were four quite ordinary, very special folk. John Phillips, Michelle Gilliam, Denny Doherty and Cass Elliot.

“They sang about a dozen songs to the accompaniment of John's acoustic guitar. They sang their whole career ‘California Dreamin',’ ‘Monday, Monday,’ ‘I Call Your Name,’ ‘Creeque Alley.’ I heard ' em all. Lou smiled. ‘Whadja think?’ I thought a lot.

“I knew my mate had his Mick and Keith in one and that was what was important. The group was almost a backdrop to what Lou and John were about, changing the name of the game and keeping it interesting.

“The Monterey International Festival production office was on Sunset Strip in Hollywood I was in self-imposed exile from the UK. In late '66 the Rolling Stones had returned to England for a rest after four years on the road. The drugs were working for and against us. I started getting calls from the fuzz warning me about Brian Jones and the condition he was in driving his Rolls-Royce up and down the Kings Road. The party was starting to be over. It was definitely over when I got warnings that I was about to be busted. So I let my bottle go and fled England for Los Angeles.

“These white kids in the audience were in school. We all grew from the diversity presented in those three days. Monterey Pop gave service; it still does. I remain oh, so proud I was there and was a small part of it. Otis; the Who; Jimi Hendrix... every time I think of the music I remember the sea of faces and the rhythm of one of the crowd.

“On so many levels the Monterey International Pop Festival began what is still with us today.”

The Monterey International Pop Festival Foundation (MIPFF) is a non-profit charitable and educational foundation empowering music-related personal development, creativity, and mental and physical health.

“I can’t separate myself from the festival, the event, the experience, and the products generated from Monterey, even as a fan, because I’m still in it,” observed Adler.

“It’s not like something that I can look back on ‘Oh, 40 years ago I was involved.’ I’m involved in a daily basis. And dealing with the ancillaries, and I’m always dealing with somebody who wants a film clip, so I have to review it. We did this festival, Otis Redding did this performance, is this clip the way they want to use it? I’m managing the act in a sense.”

In fact, by popularizing Southern California pop culture, as much as anyone, Adler caused the music industry to shift its base in the 1960’s from New York to Los Angeles.

Adler is identified inextricably with Los Angeles’ musical culture. With an uncanny feel for the public mood, he has been at the forefront of launching national and international trends as surf music, independent production, live recording, protest rock, progressive rock, rock festivals, charities, public service, films and soundtracks, "boutique" record labels, rock comedy, multicultural rock, solo songwriter-singers, rock theater, and night clubs.

In 2007 I conducted a series of interviews with Adler.

“Jerry Leiber is why I went into the record business in the 1950s,” Adler gladly confessed. “I was at a place called Ben Pollack’s Pick-A--Rib on Sunset Blvd. that later became the Body Shop strip club. Ben hosted these music jams-mostly jazz and Dixieland. And Jerry came in right off the street as he was on the charts with his partner Mike Stoller with ‘Black Denim Trousers and Motorcycle Boots’ by the Cheers. He was like a super star, a celebrity and the amount of girls who sat down at his table. Herbie Alpert and I exchanged looks. I said ‘this could be an occupation…’

“Herbie, being a horn player, wanted to make a life in music. We started fooling around writing songs and this was going to be our job.

“Going back to my early days with Sam Cooke and Bumps Blackwell I was always a song man. The first thing that Bumps, Sam’s producer, a man who came out of Seattle with Quincy Jones when he was 16 or 17, Bumps took us to school. He made us go through stacks of demos, made us break them down. ‘What was good about the first verse?’ ‘The second verse?’ ‘The bridge, and how do you come out of the bridge?’

“So, from the beginning part of my career in the music business I was a song man. That was very important to me. When I’m working with Carole and she is playing me these songs, she is playing songs that are the best. From track to track, you don’t get a bad song. You might get one song that had a problem with sequencing, but for the most part they hold up piano and voice.

“At Aldon Music Lenny Waronker brought Randy Newman to meet me and I gave Randy a stack of Carole King demos. I thought that was the best education that anybody that wanted to be a songwriter could have. I mean, at one point I said to Snuff Garrett, who was producing Bobby Vee, ‘I’ll let you hear this, but you’ve got to give me the demo back,’ because they were keeping the demos.

“Well, the thing that she did in singing and playing -- and she also sang all the parts that eventually would show up on the follow up records, the hits. Once a producer got a hold of her record, she pretty much laid out the arrangement, both instrumentally and the vocal parts that would end up on the record.

“Her demos when I first started working for Aldon Music, the way that we worked, Donnie Kirshner, myself and Al Nevins, and the staff would find out what particular artist that had a hit and was looking for follow ups.

“That assignment was then given to all the writers to go to their cubicles and knock out some songs. They were there from the beginning. And actually wrote the song. I mean, she -- History shows most of her hits, until she became a recording artist and wrote ‘You’ve Got a Friend’ and ‘So Far Away,’ were with Gerry Goffin. They didn’t just write records, like in ’58 and ’59, for Fabian and Avalon. But they wrote songs first, and then wrote the record and showed how the song should be interpreted.

“Gerry Goffin is one of the best lyricists in the last 50 years. He’s a storyteller, and his lyrics are emotional. ‘Natural Woman,’ ‘Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow’ both on Tapestry.

“These are perfect examples of situations, very romantic, almost a moral statement. Coming out of the 1950s, with the type of bubble gum music, and then in 1961, Gerry is writing about a girl who just might let a guy sleep with her and she wants to know, ‘is it just tonight or will you still love me tomorrow. Goffin could write a female lyric. If he could write the words to ‘Natural Woman,’ that’s a woman speaking. Gerry put those words into Carole’s mouth. He was a chemist before he was a full time lyricist. He’s very intelligent and obviously emotional.”

Goffin-King penned a slew of terrific US and UK hits: "Will You Love Me Tomorrow" (Shirelles), "Some Kind Of Wonderful" Drifters), "Halfway To Paradise" (Tony Orlando), "Every Breath I Take" (Gene Pitney), "Take Good Care Of My Baby" (Bobby Vee), "), "The Loco-Motion" (Little Eva), "Up On the Roof" (Drifters), “Go Away Little Girl" (Steve Lawrence), "Don't Say Nothin' (Bad About My Baby)" (Cookies), and "One Fine Day" (Chiffons). In fact, it is widely reported that Carole King played the opening piano riff on the recording.

Another monumental Goffin/King pairing is "Hey, Girl" (Freddie Scott). King also collaborated with Howie Greenfield on “Crying in the Rain," a session that Adler produced for the Everly Brothers while they were on a tour in Omaha, Nebraska.

King’s own record on the Aldon Music-initiated Dimension label, “It Might As Well Rain Until September” reached number 3 in the UK charts in 1962 and Top 30 in the US.

John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and George Harrison were Goffin and King fans. Harrison sang the lead vocal on G&K’s “Chains.” Carole and Gerry’s “Don’t Ever Change,” initially attempted by the Beatles in their Decca Records audition recording, was cut by the Crickets, and discovered via bootleg, and covered years later by Brinsley Schwarz and Byran Ferry. Mickie Most produced "I'm Into Something Good" for Herman's Hermits as well as “Don’t Bring Me Down” by the Animals.

Phil Spector recognized the Goffin and King songbook as well. He produced two Carole and Gerry gems for the Righteous Brothers, "For Once in My Life" and "Hung on You.”

“But you see, they were like gold dust, these demos,” admitted Andrew Loog Oldham, about those Goffin and King “demonstration records.”

“Those demos, I remember -- To start with, the weight of the acetate and the weight of the playing, the suggestion of the playing. It was just the space that -- The amazing ability, still, to leave space that suggested what someone should -- I mean, Dusty Springfield should know.

“Lou and I were part of the new breed of producers who participated in a different way with the artists we record. But what Carole, the songs of Carole and Gerry Goffin and with whomever she was writing served was that old -- in England, the Mitch Miller -- Well, not Mitch Miller, because he was an accomplished musician. But the model of where the producer, be it Johnny Franz with Dusty Springfield, they would give it to the arranger and see what he came up with.

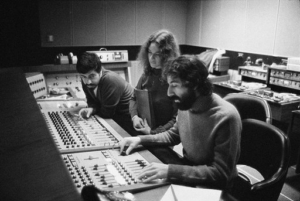

Engineer Hank Cicalo, Carole King, and Producer Lou Adler, at the mixing board during the "Tapestry" recording sessions in January 1971. Photos by Jim McCrary, courtesy of Lou Adler Archives.

“And so from the demo, the arranger did the parts, and the parts were there. I mean, when you heard -- It’s like the ability -- It’s actually the ability to sell. And we go back to like Tin Pan Alley and the people on the back of trucks, of flatbed trucks, playing -- selling the sheet music. This is the gift that then permeated its way through people like Jerry Herman and Alan Jay Lerner and the writers of those times. And because it was the same streets as ‘The Sweet Smell of Success,’ there it was, on Broadway, in 1650 in Aldon --And that great gift, and the -- I mean, Mitch Murray with ‘How Do You Do It?’ didn’t quite have it. Yeah. I mean, John Lennon at a piano, that’s a different story.”

It was Andrew Loog Oldham who brought to the Stones “Down Home Girl,” a Leiber and Artie Butler song, originally sung by Alvin Robinson.

One afternoon on the first Stones tour of the US, Andrew and Keith Richards visited the Leiber and Stoller Red Bird Records office, where employee Seymour Stein handed ALO “Down Home Girl.”

“Of course, everything goes in cycle and one of the cycles that somewhat ended with the 1967 Summer of Love,” volunteered Andrew Loog Oldham. “The LP replacing the single as the sales chip, and the public desire for a more real intimacy with and from its artists, was the life of the svengali producer, the writing teams, the puppet artists and that whole syndrome. I say puppet for the most part, I would not include the Righteous Brothers in that department, for if they had not been the artists on "Lovin’ Feeling" it would not have been the most played record of the last century. That record, "You've Lost That Lovin’ Feeling" was the zenith of collaborative perfection between dreamer, writer, production and performance. When I first heard it in Phil Spector's office I seriously thought I might be listening to three records at the same time. I looked at the turntable for some trick, a triple turntable or something, and I was not high.

“Anyway, ' 67 took care of that for a while, at least until the homogenized polished version of the same that crept back in at the end of the 70's and 80's. But, what had started with Mitch Miller and was taken over by Atlantic; Jerry Wexler; Bob Crewe; Pomus and Shuman and Leiber and Stoller, then uprouted and seized by Spector; Goffin & King, Mann & Weil and Sedaka & Greenfield, that day was done.

“Actually, Bacharach & David was probably the most real but that went out the window as well. All that was regarded suddenly as unreal and Canned Heat had replaced the Osmonds. A new reality in various shades of ability, but recognized as ‘ours’ was with us. Of course, a lot of it faked up after the first cheque...”

“We know that the Goffin and King songs are timeless classics,” states writer Kirk Silsbee. “We all know about the demos. Jimmy Jones’ ‘Handy Man’ was a demo turned master like ‘The Locomotion.’ Carole always had something as a vocalist whereby she made up for her lack of studied vocal quality with feeling. And I think you hear that in her version of ‘Natural Woman.’ Again, there’s this feeling that overrode any musical shortcomings. When she did it I don’t recall anyone saying ‘that’s nowhere as good as Aretha.’ It’s another flavor of soulful. Her piano playing, sense of timing, and phrasing, were all very important to her vocals.

“It was good for Carole to work with Gerry in the Aldon Music/Brill Building environment. It was extraordinary, working on demand. You can’t beat it. If you’ve got something as a songwriter and you are forced to produce. which is true of any artistic discipline where you are forced to produce. You either rise to the occasion or you don’t. Those people rose to the occasion. When Kirshner sold the Aldon Music catalogue to Screen Gems and the songs went to the Monkees, the world changed. Obviously, Harry Warren and the Tin Pan Alley writers were under the gun, too.

“With her own version of ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ on Tapestry she’s a woman now. Like on, ‘Natural Woman,’ something about that plaintive, emotional voice. That’s a pretty right from the heart solitary statement. You don’t get the slick arrangements or the voices of the Drifters. She’s taking it back to the root.

“The Goffin and King songs were very musical. They don’t need to apologize for those songs on any level. You get a few like ‘Up On The Roof” that outlive their time. Same with ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow.’

“The Brill Building people were in artistic competition as a very healthy thing. The couples there were the same age, all under the gun. some better than others. Leiber and Stoller showed the way for those people, not only as writers, but with an eye toward production. The role model was Leiber and Stoller who were always two or three jumps ahead of Goffin and King, Mann and Weil, Barry and Greenwich, Sedaka and Greenfield.

“Until Shadow Morton came along, even though he had not been at the Brill Building, he was there to reap what Leiber and Stoller had sown. His songs and productions are teen dramas where the he takes the concept of the playlet and extends it.”

“Maybe the first sign that Carole King was set to make a definitive break with her successful but semi-anonymous identity as a Brill Building hit-machine came with ‘The Road to Nowhere,’ underlines author and journalist, Richard Williams, “a 1966 single full of drones, bells and angst which, despite being widely ignored, seemed to predict the coming sounds of both the Jefferson Airplane and the Velvet Underground.

“Three years later came Writer, an album that prefaced the era-defining Tapestry. As well as new compositions, Writer included songs already familiar from earlier versions by other artists: ‘No Easy Way Down’ (Dusty Springfield), ‘Goin’ Back’ (the Byrds) and ‘I Can’t Hear You No More’ (Betty Everett). King was letting us know that she was now ready to repossess her own material and step out into the world.

“Listen — and marvel. 1966! On the Dimension label in America and released in the UK on London American. I reviewed it for the Nottingham Guardian Journal. Blew me away. Somehow it seemed closer to ‘A Love Supreme’ than to ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8uCGjTWlXzc

In 1967 the Byrds released “Goin’ Back.”

“[Producer] Gary Usher got the tune and brought it to us in the studio and played it for us as a demo,” Byrds’ bandleader Roger McGuinn reminisced in a 2007 phone interview with me. “I didn’t know of Carole King, even though I had worked in the Brill Building earlier on with Bobby Darin. And, I had never heard of the Goffin/King songwriting team. But I loved the tune and thought it was really good.

“Gary explained that these were Tin Pan Alley writers who had just kind of taken a sabbatical and come back and revamped their style to be more contemporary, like we were doing. So it really fit well I thought. We learned it and put a kind of dreamy quality into it.”

“Goin’ Back” was subsequently recorded by Nils Lofgren for a live radio broadcast for KSAN-FM from the Record Plant in Sausalito, Ca with Al Kooper sitting in on piano.

“I was getting ready to do my first solo album with producer David Briggs,” Nils mentioned to me in a 2019 conversation. “I was vaguely aware of the Brill Building, a songwriting edifice if you will. There was Motown with Holland-Dozier-Holland. Thanks to my piano work, my first professional session was on Neil Young’s After The Gold Rush, which was very fish out of water. Neil and David Briggs felt I could handle some simple parts, so David Briggs encouraged me to write more on piano.

“I was aware of Goffin and King’s ‘Goin’ Back’ from the Byrds. So I started messing around with the ‘Goin’ Back’ song as a possible cover and staying at Art Linson’s old cabana at the Malibu Colony, I was freeloading at the time, on the beach. A funky room with an upright piano, I was writing. And I was looking for an arrangement to explore of that great song. And I found myself more on the piano than the guitar that felt right, and came up with that piano riff and groove.”

Shelia Weller, author of the 2008 book “Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon -- And the Journey of a Generation (Atria) offers her insights into King’s collaborator poet and lyricist Toni Stern.

“Carole found her complement in lyricist Toni Stern. Toni, who’d grown up on the Sunset Strip (where her mother managed a nightclub); was a strikingly pretty, willowy bohemian; who wrote irony-tinged lyrics that reflected the slightly battle-hardened insouciance of the new hip, single woman. They played off each other.

‘There was a practicality in Carole that was comforting -- I would hand her a whole lyric, neatly written out, and she would sit down and we’d have a song within hours,’ Toni told me, during interviews for my book. ‘Working with her made me feel validated, like I wasn’t a wild child.’ Similarly, ‘I’m sure there was a California quality in me that appealed to Carole. She was moving from a familial, middle class lifestyle to Laurel Canyon, where she started to let her hair down, literally and figuratively. We worked off our contrasts.’”

Toni Stern and Carole King supplied songs for the Monkees including their seminal feature-length movie, Head. Goffin and King crafted "Take a Giant Step" and "Pleasant Valley Sunday” for the group. King, in fact, played guitar on the Monkees’ “As We Go Along.” Percussionist Denny Bruce remembers Carol was the piano player on the session date for the Goffin/King “Porpoise Song” that his pal Jack Nitzsche arranged.

The Goffin and King songwriting partnership ended in 1968, after their divorce, as Carole King began to pursue a solo recording career again.

In that decade, she, Goffin, and entertainment and music columnist Al Aronowitz founded their own short-lived New Jersey-based record label, Tomorrow Records; Charles Larkey, the bassist for the Tomorrow act, the Myddle Class, would become King's second husband after her marriage to Goffin dissolved.

King and Larkey then relocated to Southern California, Hollywood’s rustic Laurel Canyon area. This former Brooklynite was feeling emancipated…and newly Laurel Canyon-ized.

In 1968 they founded The City, a trio rounded out by New York musician Danny “Kootch” Kortchmar. Jim Gordon served as guest drummer on The City’s sessions that yielded one LP, Now That Everything's Been Said which Adler produced. King chose not to tour at the time, partially due to stage fright; which hampered the album’s commercial success. However, it did contain songs later popularized by the Byrds ("Wasn't Born to Follow"), and Blood, Sweat & Tears ("Hi-De-Ho")

“I had a friendship with Carole,” said Adler. “That came from working as her publisher in a sense from having the West Coast office of Aldon Music. So, that when she moved out her in 1968, and I had known her since 1961. I was one of the people in California of a small group that she knew, so her coming to record with me was sort of natural. If she was going to record it was a person that she knew from the Aldon days. It was that sort of relationship. I was involved with her kids, somebody that was around her family and really cared about her daughters.

“After The City album and Writer Carole began writing for herself. Watching her writing her own lyrics as the principal lyricist I saw her develop as a lyric writer, ‘You’ve Got a Friend,’ a famous Carole King song. She was not confident as you can imagine then in writing lyrics, having worked with Gerry, as I’ve said, arguably one of the best lyricists over the last 50 years.”

“We did rehearse in somebody's office. Maybe a Screen Gems office with Eddie Ho playing drums...nothing ever came of it,” Danny Kortchmar wrote to me in a 2016 email. “I played on Carole's demos and we did them all over town. So that's what we were doing on Sunset Blvd. at [Art Laboe’s] Original Sound in Hollywood.”

King’s recordings utilized two drummers Joel O’Brien and Russ Kunkel. “They were very different drummers. Joel was jazz trained and had a lighter touch, but Russ was more solid of a rock musician,” suggested Danny.

Kortchmar was always a fan of Lou Adler’s studio productions.

“I thought Lou was the coolest cat there was...great laid-back attitude in the studio, always got across what he wanted to hear with minimal speech…had already made history, had the foxiest chicks, the best taste....I was in awe. After I started doing more and more sessions for different producers it was re-affirmed for me how great he was.”

Toni Stern and Gerry Goffin contributed to The City group, and the following album, Writer was “a Carole King vehicle,” but Carole could lose herself in a band identity and not be viewed as “Carole King’s new thing.”

Adler was producing the movie Brewster McCloud and couldn’t be the producer on King’s solo disc, Writer, which John Fishbach engineered and Gerry Goffin mixed. Tracks on Writer implement “Up on the Roof” that was a number 4 hit for the Drifters in 1962, and "Child of Mine", which Billy Joe Royal. All the songs were by Goffin and King, while Stern’s lyrics informed "Raspberry Jam" and "What Have You Got to Lose.” Toni would eventually co-write “It’s Too Late” on Tapestry.

In May ‘70 King’s Writer with a Guy Webster-shot cover photograph was released and serviced to distributors, rack jobbers, radio stations and music periodicals.

During November 24-29 ’70, King was James Taylor’s pianist when he debuted at Doug Weston’s Troubadour club in West Hollywood. King played ‘You’ve Got a Friend’ at their sound check and it was included in the engagement’s repertoire.

Heather Harris is the former UCLA Daily Bruin Entertainment Editor, now a well-respected music photographer who assigned the first ever review of King’s Writer LP.

From 1968-1972 Harris oversaw the Icon and Index section of the trend-setting college daily published in Westwood, California.

“At The Troubadour before Tapestry was out I saw James Taylor introduce Carole when she performed with him on piano with something to the effect as ‘very talented and not so well known.’ I loved the Guy Webster album cover of Writer. That is what got my attention at the school paper. I was later primed for Tapestry.

“During my tenure at the UCLA Daily Bruin I first saw the Writer promo photo with the maxidress, sold at Contempo Casuals, then the Tapestry album cover. It was a new style of early ‘70s, very different from what came across the desk in Westwood California. Natural light and not an album cover short in a photography studio. It looked like it was actually shot in her home, sidelight coming in from the right.

“The whole package and especially the cover made a big impression. The power now is diminished in the CD format. The LP covers then were vital for exposure and made impact. Now if you’re not on YouTube you’re not gonna know what they look like.

“It was obvious Carole King really was going to be a successful singer/songwriter in that era of the business, in a way that Carole Kaye was a successful bass player in the music business. Both are strong female figures. Even if they are not loud people, they succeeded.

“Carole had cross appeal because she sounded like her audience. The initial core people in the throng who believed they could have written it. It’s deceptive like the way actresses like Jennifer Aniston of Friends has a huge female base. They think they can sort of look like her if they gave the effort. In the same way a lot of her audience thought they sort of sort of thought they could write really nice songs like ‘So Far Away’ if they realty gave the effort. Forgetting of course, that people who are really good at something make it look easy. I really give her credit what she was doing at the time what she did. She made chill out music. Everyone else was tossing the words and music in our face at a louder level. Laura Nyro was first,” reinforced Heather.

“On Tapestry here is someone who looked like she was similar to our age but even if she was older. And a lifestyle of a rich hippie, and she does these nice songs. Carole looked like the audience. Laura Nyro didn’t. I liked Laura Nyro a lot. But I was also chilling out to UK folk rock like Fairport Convention and Pentangle.”

Chris Darrow was a co-founding member of the Kaleidoscope and a pivotal session musician on the debut Songs of Leonard Cohen, John Stewart's Willard, James Taylor, Sweet Baby James, and recording dates with Larry Williams, Johnny “Guitar” Watson, Hoyt Axton, John Fahey, Gene Vincent, Nik Venet, Kim Fowley, Jack Nitzsche and Denny Bruce.

Fiddle player Darrow suggested Sunset Sound studio in Hollywood, engineer Bill Lazarus, and drummer Russ Kunkel to the producer of Sweet Baby James, and recommended two bassists, John London, and the Poor’s Randy Meisner, the future founding Eagles’ member. Darrow also called pedal steel wizard Red Rhodes for a session.

Multi-instrumentalist Chris Darrow set the blueprint for the emerging Southern California singer/songwriter genre. Darrow was a true insider and attended the wedding of Carole King to Charles Larkey at her Laurel Canyon home.

“I went to the Troubadour when Tapestry was out,” Darrow remembered in a 1998 interview we once did at 3:00 am.

“I saw the early show. It was crowded and almost all the people in the room were women, mostly high school and college age. Almost all of them were with their mothers. I knew Carole King because she played on the Sweet Baby James album. James’ album changed the entire visibility.

“In a way it also symbolizes New York coming to L.A., with Kootch and Charlie. Ralph Schukett was in Clear Light. But JT was the penis for the whole thing and made it happen.

“It went back to The City album. Abagail Hannis had sung in The City and she was one of the leads in the Los Angeles production of HAIR at the Aquarius Theater in Hollywood. I caught HAIR when Abagail sang the night Jennifer Warren (Warnes), the main lead star, had her night off. Hannis and Delores Hall sang on Writer.

“At the Troubadour Carole just played by herself and was really good. One of the things that most people don't understand is that she is a consummate songwriter. She knows form. As a person who played piano for songwriting demos, she had to play the essential song and play everything right down the middle. She was not playing solos, she was playing the song. Consequently, as a songwriter and a person playing piano on demos, her great ability was to center in on the song.

“That's why Carole was so good with James Taylor. She played the song. She played big chords. She played something that was hook-oriented that fit the song. So for her as a piano player it wasn't about chops, it was about style all the way. So, Carole wasn't somebody who was gonna play big solos. She was going to accompany the song and play the song. Playing the song is different than playing lead or rhythm. That's why she is so good. Underneath it all, she is still one of the consummate songwriters of our time. She and Gerry Goffin wrote some great songs together and she also wrote alone, as a solo artist. She's very talented.

“I don't think that Carole King is a fabulous singer, but I think that she really knows how to interpret her own stuff. When she was first doing her demos with Gerry, people would always sing the songs the way she sang them, which means that she had great phrasing. She is not a bad singer by any means. It’s like Johnny Mercer, who was a great singer but didn't have a great voice. But he was still a great singer, because he knew how to sing his songs as good as anybody.

“Carole King is a songwriter foremost, and it is deeper into that arena than anything else she does as a singer or piano player. Her ability to understand and present a piece of material so that its stripped down to its basic elements is what I think her major contribution to the singer/songwriter thing was.

“One of the things about James Taylor was that his singing, his songs and guitar playing all went together. The singer/songwriters were generally people who played with one instrument, mostly guitar and sometimes piano,” declared Darrow. “They would have bands, but basically it was based around them and their instrument like James, John Stewart or Jackson Browne. And so the idea of having a style that backs up what you are trying to say is a really hard thing to accomplish, but also very elemental at the same time.

“She was from New York, and already had major hits as a songwriter. Carole had an understanding of the world of music in a whole other way than most of the songwriters. She was very fortunate to come out of the Brill Building experience on a Teddy Randazzo level. She spoke to women. She wasn't a babe, like Linda Ronstadt. I played with Linda 1969 -1972 and was her road manager for a while as well.

“In Carole's photos, cover art, and such, she wasn't selling sex,” added Darrow. “She wasn't selling that romantic thing. That's why I think women took to her. She was like every woman. She had this way of speaking to the women of the time in a way in a way Joni Mitchell and Linda Ronsdadt didn't.

“When Carole sang ‘Natural Woman,’ a song she co-wrote with Goffin and Jerry Wexler, who suggested the title, she sings it in a whole different way. And she doesn't mean it like Aretha means it. She means it on a Laurel Canyon and a Topanga Canyon level. She came from New York and was now wearing Levis and letting her hair go natural. She could be a Jewish girl with no makeup. That was cool,” exclaimed Chris.

“I played on an album of a Japanese composer/keyboardist and vocalist Myumi Itsuwa that Carole played on. It was recorded at Crystal Studios with John Fishbach producing, who also produced King’s Writer. He would later on engineer my first album, Artist Proof, on Fantasy records in 1971.”

Sirius XM deejay and veteran music tastemaker, citizen of Hollywood, Rodney Bingenheimer proudly owned Writer.

At King’s famed 1971 Troubadour club opening, Rodney, then a weekly columnist for GO magazine, totally dug King’s live set but left with some reservations.

“I knew her name and loved the songs she wrote over the years, especially the things for the Monkees. I went to see Laura Nyro at the Troubadour earlier and wrote about it for GO magazine. I loved it! Not what I saw her do at the Monterey International Pop Festival in ’67.

“Carole King at the Troubadour was a hippie girl on the piano bench, but like a soul singer, and I knew she wrote the songs. But…I thought it was going to be like a big soul and pop music gig. Loud, pop. ‘Lou Adler-type’ music: Jan & Dean, Mamas and Papas, ‘United Western’ (recording studio) music. Tambourines and hand claps. I was shocked. I liked it a lot. It wasn’t boring but I was hoping it would be like Monkees’ songs, Spector covers, and the things Carole King did with Gerry Goffin. Like ‘The Porpoise Song.’

“It was now a change in the music coming from Laurel Canyon. It was music that was from Micky Dolenz’s refrigerator that had organic apple juice and lots of hippie food. The audience was over age 21! I wasn’t used to that coming out of the sixties and the Sunset Strip clubs. I was sort of hoping some of the Shirelles would walk off Santa Monica Blvd. and join her on stage for ‘Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow’ Bingenheimer comically lamented.

Just prior to Tapestry was the deregulation of the FM bandwidth, which resulted in a mini-explosion of so-called new 'progressive' or 'underground' or 'free-form' radio stations eager to spotlight their own artists and playlists separate from the mainstream Top 40.

Arriving in late-March 1971, Tapestry, struck a universal chord at an opportune time in pop and rock music history - the intersection of folk-rock's introspective and a socially conscious sense of disturbing forensic romanticism in a planet-gone- wild.

With the escalating rise of West Coast naturalism centered in the saturated Los Angeles music sector known as Laurel Canyon. Jim McCrary’ took the cover photo in King’s Laurel Canyon home living room.

In April 1971, King’s close pal James Taylor - who played on five Tapestry tracks – released "You’ve Got a Friend" as the first single from his new album, Mud Slide Slim and the Blue Horizon.

“Having left the restrictions of the Brill Building songwriting world, the late ‘60s and very early ‘70s brought some artists who brought a new sensibility, writers who reacted against writing for others and chose to go out and ‘do your own thing,” posed author and keyboardist Kenneth Kubernik.

“At obviously at a certain point Carole made the transition of being the artist and product herself, She makes the transformation doing her own thing, finds the strength and character to get over her fear of performing and works herself, as her fellow artists are going through the same arc. Neil Diamond left the staff writing songwriting world. Carole and others all start making this move, going from the impersonal, the large product placements to the very intimate and personal. It’s a narcissistic act on one level because going from the impersonal to deploying ways that were very subtle.

“She caught the zeitgeist. She got the wave. The right place at the right time. She was just edgy enough, not so far out, she wasn’t in her ‘Blue Period’ which is so impenetrable that even to this day half the people don’t know what Joni Mitchell was singing about. OK. And, the industry was really comfortable. A sense of her willingness to come out and sing in post-Dylan world you didn’t have to have a perfect voice.

“You had to have an individualistic sound. This emerged from Writer, developed as singer and tunesmith from her work in The City’s album, and teaming with Adler as focal point. Rhythm section and principal musicians had recorded with Carole and Lou.

“The strength of Writer and evidenced more on the Tapestry material was that they were structurally sound. The melodies and lyrics were there. The mix finessed a lot of deeper feelings. Collectively there is a suggestive quality in all the songs that connote something much deeper. There is an inherent strength in the way the best verses and choruses flow into each other, which allow them to stand the test of time.

“Tapestry is a sea change in the record industry for this golden period.

“When it’s just her singing the songs you get the sense that this is an individual who had a voice that needed to be heard. Whether she was on the piano or not, it was her willingness to make herself emotionally available to her public and to not be afraid. You could deny the emotional potency of these songs, and where or not she was playing the piano which was irrelevant. She’s not Nina Simone or Aretha Franklin, both brilliant piano players. Nina went to Julliard to be a classical pianist.

“Hearing them a half a century on the radio, you don’t reach for the button the way you might have in 1970 or ’71.

“She has been climbing a road from being invisible from 1961, employed, but no possibility of her being at artist, she did have a hit ‘It Might As Well Rain Until September,’ but ten years later, her first move, like some sexual awakening, ‘I Feel The Earth Move’ was an opportunity for her to launch her arrival. She had a real shot of taking it to the next level that was the real earthquake. The song had had an unbelievable hook, a piano hook, not a guitar hook. Very fresh, a woman speaking forthrightly. Its many social changes weren’t just sexual but informational.”

“On Tapestry Lou and I did quite a few things,” detailed engineer Hank Cicalo. “There was a thing about the middle of Carole’s voice where it’s almost warmth with a little edge. I always wanted to capture that. I thought her piano playing was great, she would sing, and she was such a writer and performer, she knew when to layout and when to hit it. So that was always great.

“You got to remember whole period everything was moving from two track tapes. I met Carole when she wrote songs for the Monkees, whom I did 4 or 5 albums with. The writer becoming the recording artist or star seemed to be a natural path for people performing as side people. And then they made an album suddenly becoming a star or an artist or performer. And see them grow, but we were all growing the producers, the record companies. The progression was natural.

“A&M studio B had a Howard Holzer special made console. His board you could really punch it. The only thing I had to worry about was tape there was no noise reduction in those days, so much easier now. Everything was supporting that voice and that piano. That’s where the nucleus of the whole album was. Then, when her vocals came, when you mixed them, the spaces were always in the right places.

“My thing with drums, in a record I did, Russ Kunkel on this, I always wanted to get the cymbals. Years ago it was one microphone over the top, that kind of thing. But because of the brushes and light cymbal work, and if you listen to those records you will hear it. It’s there. The hi-hat was very important top these records or any of these records, that’s how you sub-divide the bar. Musicians don’t listen to that but they feel it. So to me it was always important people could hear what was in the phones.”

Merry Clayton is heard on Tapestry and in 2020 currently recording a gospel album with Adler.

“I remember I was about to take a girlfriend out to dinner because it was her birthday,” recounted Clayton to me in a 2008 interview. “I told her I had to go by the A&M studio to go say hi to my husband (Curtis Amy) and Lou.

“I walk into that big main hallway and here comes Carole King. ‘Merry! Come in. You gotta do this song with me. You gotta do this one little part on this song for me.’

“I walked in the studio and I will never forget her hanging over the piano writing musical notes. And she played me the track for ‘Way Over Yonder.’ ‘Wow! I want that song.’ But she told me it was for her album. And I did my part.

“The song was so fabulous and so churchy to me. So what I love and so what I love doing. And I walked in and nailed it. And Lou and Hank Cicalo the engineer were in the vocal studio C. I was walking down the hallway to leave and I heard it and came all the way back. Oh honey. I was standing next to Carole holding her arm and said, ‘Oh Carole, this is just so good.’ I was on a few other songs. ‘You’ve Got a Friend,’ ‘Smackwater Jack,’ and ‘Where You Lead,’ that I did background vocals on with Carole and Julia Tillman.

“Carole King had church in her vocals. You know why? Because she was around church, honey. Carole was around soulful beautiful people. When you surround yourself with soulful beautiful people can nothing come out of you but soulfulness and beauty, and she surrounded herself with that.

“Honey, Tapestry was an anointed project,” hailed Clayton. “It had God all over it as far as I was concerned, because I could feel it. You know, when you feel stuff. You can feel that music and you can get a little tingle from the back of your neck and up my back. It had magic. It was absolutely magic.”

It was KMET-FM in Los Angeles who would debut the platter. Deejay B. Mitchel Reed had several selections in heavy rotation at the popular radio station. Adler and Herb Alpert went back to the very early sixties with BMR. They managed him when the jock was at KFWB on the AM dial.

In 1972, the still influential R&B deejay the Magnificent Montague, on his XPRS AM radio shift in his inviting tones would shout and tout “It’s Too Late.”

“Listen to the sister sing, and listen to Lou baby swing!” Adler knew Magnificent Montague from his Sam Cooke years.

Tracks from Tapestry blared worldwide and were spun on various radio formats nationwide.

King’s 1970 and ’71 LP’s inspired consumers, non-performers, and music business veterans. Carol Schofield named her record label MsMusic Productions, and also owns High Desert Records in Yucca Valley, Ca.

“When I worked at Wherehouse Records in San Francisco in the very early seventies I have fond memories of customers regularly buying Writer and then Tapestry. It was very different foot traffic than from a year earlier when a lot of LP purchases were the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, the Rolling Stones, Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead and Doors.

“Writer and Tapestry are still revered. It’s timeless. Classic...Carol King is definitely a ground breaking female songwriter artist pioneer who rose above a traditional male dominated arena.”

Dr. James Cushing of the English and Literature department at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo is a deejay on KEBF-FM in Morro Bay, Ca. He hosts the weekly Friday music show Miles Ahead. Prof. Cushing has programmed King’s catalog for decades.

“Part of what she was bringing into Writer and further with Tapestry was that Brill Building enthusiasm combined with an early ‘70s melancholy. During her Brill Building days, she wrote songs of innocence -- teenage dreams coming true. But after 1968, we knew that not all of our dreams were going to come true. Some of them get shot to death in the kitchens of hotels. Tapestry has a secret political message: it's too late, baby. .

“Writer and Tapestry also reiterate the regional impact of Laurel Canyon on not only King’s music but her vocal prowess. These are songs written in the fabled 90046 hip zip code. These audio statements were not crafted in cramped cubicle in an office New York or a home in New Jersey.

“The climate and weather of Southern California informs the songs and surely the vocal performances. Your freedom of movement and physical comfort is limited in East Coast. The parallel of the limitations of the East Coast weather puts on a person and a creative force and the limitations of the Brill Building. I would offer the natural and organic lifting of those limitations that you get in Southern California. OK. Earthquakes, rain storms, fires but these mother nature acts do not happen every year.

“To live in New York and her early compositions and pairings with Gerry Goffin you are aware that you are always obeying and dealing with the things the city deals you out, Laurel Canyon, Appian Way, they give you that sense of protection from the world simultaneously with easy access to it. What happens with her songwriting, singing and lifestyle is that they all open to reveal what had already been there. A kind of winsome yearning that contains adult experience, i.e. New York, but that exudes youthful exuberance, i.e. Los Angeles.

“The bulk of the songs were written in Hollywood, and the vocals were done in Hollywood. Every one of her vocal reflections and nuances are pre-measured and deliberate, almost story boarded like directors Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick, still feel it is fresh, authentic, feel that it comes from an adult sensibility. You still feel it has depth. You still feel these things often associated with the New York style. But yet, you also feel and hear the things we associate with the light, space and airyness of Southern California.

“Tapestry was recorded on the corner of Sunset Blvd. and La Brea Ave, not 42nd street! The songs are not about the urban theater of human passion. Carole King had the craft of fitting the words to the tune marvelously.

“One does not come away from Tapestry feeling that a literary-dramatic sensibility has been successfully harnessed to music, which is what one tends to feel with Dylan or Joni Mitchell. Part of this Brill Building craftsmanship she developed involved a simplification of poetic imagery. The songs emphasize statements over images, and if the song uses metaphor, it sticks to one metaphor: ‘I feel the earth move.’ And that one metaphor will be developed all the way through. The Motown songwriters did that too.

“Upon the initial LP release you purchased Tapestry because you had an idea of who Carole King was because you had seen her name on many of the albums and singles in your record collection or you owned Writer,” instructs Cushing.

“After playing Tapestry you discover producer Lou Adler. His Ode label issued Spirit albums before Writer and Tapestry. Isn’t that enough? John Locke of the group lived in Laurel Canyon in the mid-60s before he relocated to Topanga Canyon with the rest of that band. Ode is a label that gave us Spirit’s ‘Nature’s Way’ first and then King’s ‘I Feel the Earth Move.’”

Carole King discussed the evolution of her songs to Lou Adler in a 1972 A&M studio promotional interview.

In a recorded conversation between King and Lou Adler inside A&M Studio B on October 18, 1972, in Hollywood, Ca. King shed light on her songwriting aspect of Tapestry.

“The music is always again inspiration but I have more control of the musical inspiration. In other words, if I get a musical idea, if I just get a glimmer of a musical idea, I can make that go much more how I want it to go. If I get a lyrical inspiration I really have to work hard at controlling it. I really can’t control it. And most of the good lyrics that I have written have just sort of come to me without any control. The only control that I excerpt is in editing which I’ve always done to Gerry’s lyrics and Toni’s lyrics. I’m a very good editor and that’s the craft.

“Once I got to the stage of recording I have feelings of wondering about whether it going to make it or not for a time, but the big questions about, you know, whether it’s going to make it or will people like it, all the big insecurities really happen when I’m writing the song. Once the song is being written and once it’s finished and I play it for you, and a few people whose opinions I respect, I begin to get a feeling. Sometimes I already have the right feelings. Sometimes I don’t know. Sometimes I don’t know.

“When I write my own lyrics I’m conscious of trying to polish it off but all the inspiration is really inspiration, really comes from somewhere else.”

King spoke to Adler about her composition “You’ve Got a Friend.”

“Once I got to the stage of recording, I have feelings of wondering about whether it’s going to make it or not for a time, but the big questions about, you know, whether it’s going to make it or will people like it, all the big insecurities really happen when I’m writing the song. Once the song is being written and once it’s finished and I play it for you, and a few people whose opinions I respect, I begin to get a feeling. Sometimes I already have the right feelings. Sometimes I don’t know. I didn’t write it with James or anybody really specifically in mind. But when James heard it he really liked it and wanted to record it. At that point when I actually saw James hear it, I watched James hear the song, and his reaction to it. It then became special to me because of him, you know, and the relationship to him. And it is very meaningful in that way but at the time that I wrote it. Again, I almost didn’t write it. When I write my own lyrics I’m conscious of trying to polish it off but all the inspiration is really inspiration, really comes from somewhere else.

“That was because his album Sweet Baby James was recorded the month before Tapestry was recorded I think, or even possibly simultaneously. Parts of it were simultaneous. And it was like Sweet Baby James flowed over to Tapestry and it was like one continuous album in my head, you know. We were all just sitting around playing together and some of them were his songs and some of them were mine.”

In the 1972 recording studio conversation with Adler, King reflected on Tapestry.

“It was just another bunch of records, you know. Another bunch of songs that were being recorded. Now I’m much more conscious of the fact that people are kind of watching what I’m doing and waiting to hear what it is. And possibly some people are waiting hostility (giggles) and other people are waiting lovingly. At that time I didn’t feel like anybody was waiting. But even now, the fact that people are watching once we get into doing it doesn’t seem to be that big a problem. Because I’ve just been doing it for so long, as you have, that the only way to do it is to get in there and make music and get it the way you like it and don’t worry about anything.

“It is typical of the magic that seems to surround that album, a magic for which I feel no personal responsibility, but just sort of happened, that I had started a needlepoint tapestry, I don’t know, a few months before we did the album, and I happened to write a song called ‘Tapestry,’ not even connecting, you know, the two up in my mind. I was just thinking about some other kind of tapestry, the kind that hangs and is all woven, or something and I wrote that song. And, you being the sharp fellow you are, (giggles), put the two together and came up with an excellent title, a whole concept for the album.”

In one of my dialogues with Adler, I inquired about King’s growth as a songwriter since splitting New York and firing on all cylinders from her perch in Laurel Canyon.

“The climate of the late ‘60s had no women in the Top Ten charts, except Julie Andrews on The Sound Of Music soundtrack. Before the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967 I flew to New York and tried to sign Laura Nyro. I invited her to perform at the festival.

“Carole was in a group The City, who I produced for Ode in 1968. The LP was called Now That Everything’s Been Said. The City album was supposed to be a group, even though it sounds a little like Tapestry, not so much in the subtleties, but in the way that group plays off of each other. At the time Carole did not want to be a solo artist. She wanted to be in a group and she was more comfortable in a group. She didn’t want to tour that much or do any interviews. And we started to get those kinds of songs that would then lead us to Tapestry.

Toni Stern was a writer for Screen Gems, who collaborated with Carole earlier on the Monkees’ Head soundtrack and Carole’s City album, and her debut album Writer. I knew her a little bit. She was introduced to Carole by Bert Schneider of Raybert Productions, producers of The Monkees.

“I saw Toni when the songs were presented with Carole to me for Tapestry. Danny Kootch and Charlie Larkey were on The City album, they are the core certainly of Tapestry. Larkey on both electric and acoustic stand up bass and his relationship with Carole at the time, husband and babies to be. And father of babies to be. His bass was very important to the sound and feel of Tapestry.

“As music often does, it becomes the soundtrack of the particular time. What I think happened in ’70 or late ’70, ’71, James Taylor, Joni Mitchell and Carole, is that the listening public and the record-buying public bought into the honesty and the vulnerability of the singer-songwriter, naked in the sense -- You know, what James was singing about, ‘Fire and Rain.’ Their emotions that they were laying out there allowed the people to be okay with theirs. And I think the honesty of the records, there was a certain simplicity to the singer-songwriter’s record, because they either start with vocal-guitar or piano-voice.

“But she gained her confidence within this Tapestry album and I think she had been writing a little bit, but really once we started on Tapestry she felt confident enough to complete those songs. We went by songs. The only thing we reached back for, which was calculated in a way, which of the old Goffin and King songs that was hit should we put on this album? And, that’s how we came up with ‘Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow’ I thought that song fit what the other songs were saying in Tapestry. A very personal lyric.

“(‘You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman.’ Once again it’s a Goffin and King song but written with Jerry Wexler. Of all the songs on Tapestry Carole had more trepidation about doing it because of the Aretha Franklin record, but I think in the way that we did it was very much like Tapestry.