Al Kooper and Harvey Kubernik Conversations on Bob Dylan, Blood, Sweat & Tears, The Band, The Rolling Stones, Michael Bloomfield, Super Session and…Timi Yuro

Al Kooper was born Alan Peter Kuperschmidt, February 5, 1944 in Brooklyn, NY, and raised in Queens, NY.

His piano and organ work has informed the soundtrack of our lives, whether you want to admit it or not.

Al Kooper was selected for a “musical excellence award” at the 2023 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony on November 3rd at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn.

In 2001, 2004, 2013 and 2018 I interviewed Al Kooper for a handful of hours about his 1965-1970 recording endeavors with Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones and other topics.

The 60th anniversary of Bob Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited was in 2025. July 2026, marks 60 years since Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde was initially shipped to AM radio stations, rack jobbers and retailers.

Months before you’ll see and read countless articles and cover stories by writers this summer, I jumped the route reminding readers now about this landmark endeavor.

Al Kooper’s songs were covered by Pat Boone, Bobby Vee, Keely Smith, Roger McGuinn, Rufus, Gene Pitney, Tommy Sands, Freddie Cannon, the Modern Folk Quartet, Eddie Hodges, Donny Hathaway, Betty Wright, the Staple Singers, Ten Years After, Carmen MacRae, and crafting “I Must be Seeing Things” for Gene Pitney. Al is one of the co-writers of Gary Lewis and the Playboys’ “This Diamond Ring.”

Jay-Z, The Beastie Boys and Pharcyde have sampled his compositions.

Kooper founded the Blues Project, started (and quit) Blood, Sweat & Tears after one LP. He worked as a Columbia A&R staff producer, dreaming up the Super Session and Live Adventures concepts.

Al’s name can be found on tracks and album credits by everyone from Judy Collins and Joan Baez, to Phil Ochs and Peter, Paul & Mary, Tom Rush, Paul Butterfield, and Eric Andersen.

His keyboard work graces Simon & Garfunkel’s Parsley, Sage, Rosemary And Thyme, Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde, The Who Sell Out, the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Electric Ladyland, the Rolling Stones’ Let It Bleed, Taj Mahal’s Natch’l Blues, and B.B. King’s Live And Well.

In 1998, Kooper also published his revealing and educational autobiography Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards: Memoirs of a Rock ‘N’ Roll Survivor. Mandatory reading.

In the late 1990’s Kooper schlepped his massive record collection (and himself) to Boston, Massachusetts and realized another longtime dream by joining the teaching staff at the acclaimed Berklee College of Music. For four years Al taught courses at the school in the areas of vocal recording, songwriting and the history of record production. In 1999 he started the Berklee Charity “It Can Happen” Fund for Handicapped Students.

There is Kooper’s documented relationship with Bob Dylan. A Kooper hologram appeared on the Bob Dylan CD-ROM, Highway 61 Interactive, explaining how the two met and recorded "Like A Rolling Stone." Kooper wrote the segment on Bob Dylan for the Encyclopedia Britannica and a few years ago and penned one of the essays on the soundtrack album to Dylan’s No Direction Home documentary.

Kooper, the former Blues Project leader during 2003 toured Japan, and in 2007, he was inducted into the Rock ‘N’ Roll Walk of Fame in Hollywood on Sunset Boulevard. Later in the year he was named as recipient of the Les Paul Award for his life's work and was presented with the award in New York City by Les Paul, himself.

Last decade, Kooper released a solo album, Black Coffee with some wonderful liner notes by author/record producer Andrew Loog Oldham.

Q: Before we talk about working with Bob Dylan, what’s the most recent reissue you’ve acquired?

A: I just got an English Timi Yuro twofer.

Q: I like “Hurt.”

A: How ‘bout “Insult to Injury?” I love that tune. One of the things on the twofer, and as a matter of fact the only thing worthwhile owning is an album I didn’t know existed which is Live At PJ’s. It was a pretty good band. I don’t think it was a house band situation.

Q: She went to Fairfax High School where I graduated from. Phil Spector was in the choir with her there and helped bring Timi to Liberty Records after he was in the Teddy Bears. Phil helped mix the first recording of “What’s A Matter Baby” that Clyde Otis produced.

A: She was produced primarily by Ed Silvers. I knew Ed because at the time I was making a living as a songwriter. We had a song that he liked and he showed up one day with her at our office and I played the piano and she sang the song. I’m sure I popped my shorts…Oh my God…

Having her sing right behind me was like one of the most exciting things of my life. She didn’t record the song though but it was still great. The Timi Yuro event was when she came looking for material and me and the guys I wrote with at the time had an appointment with her and producer. Ed Silvers. This took place at 1650 Broadway in NYC where we used to compose our songs. She liked one and asked if I could play it on the piano in a key she could try it.

I did that but HATED that my back was to her as I was playing and I missed watching her sing my song. The song was "I'm Over You" which later was covered by Lorraine Ellison (thanks to Jerry Ragavoy). Timi sang the shit out of it but never recorded it.

Q: Bob Dylan time.

A: When I recorded with Dylan on Highway 61 Revisited it used to be on 799 7th Avenue. And that was Columbia Records and they had the studio in the same place as the offices. So, when moved to Black Rock they then moved the studio further east. So, it was on 49 E. 52nd

They had the same monitors and the same gear at every place. In those days they had rotary pots instead of faders that slid up and down. It was very archaic. It was also a union shop. With required breaks every three hours. If you were signed to Columbia, you couldn’t record at any outside studio.

Q. The record producer Tom Wilson.

A. Wonderful guy.

Q. I heard you used to steal Dylan acetates out of his office.

A. I did. I was a bad boy.

Q. He gets overlooked in history.

A. So does John Simon, by the way. Tom earlier worked for Savoy Records. He was a very bright guy. He was a very high-class guy.

He was like ‘what’s happening man?’ That kind of guy. But you knew he was bright and he talked about very erudite things, and he really saved my life that day on that Dylan ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ session.

Because, he could have…I went to him and said, ‘Man, let me play the organ.’ They had just moved Paul Griffin from the organ to the piano. And I went over to Tom Wilson, and I was invited just to watch, you know. And I said, ‘Man, why don’t you let me play the organ? I got a great part for this.’ Which was bull shit. I had nothing. And he said, ‘Man…You’re not an organ player…’

And then they came to him and said, ‘phone call for you Tom.’ And he just went and got the phone. And I went in to the studio and sat down at the organ. He didn’t say no. He just said I wasn’t an organ player. OK.

That was the moment he could have just thrown me out and rightfully so. And you know what? He didn’t. And that was it. That was the beginning of my career. Right then and there. That studio dialog is documented. Wilson is the guy who invited me to the session first of all, which is really nice. You didn’t get invited to Bob Dylan sessions, you know, especially if you were a nobody like I was. And there it was. There was the chance he had to toss me, and it would have reflected back on him because he had invited me to the session.

Q. On that “Like A Rolling Stone” date, was there a reason why you “played behind the runner” on the track? The organ slightly follows Dylan and the other musicians.

A. No I did that because I was waiting to see what chord they were going to do. There was no music or lead sheet, or anything. I was just playing by ear and I didn’t want to be the one making a mistake because I was doin’ like a rebel run there. But anyway, we played together on that session, and the rest of the album.

Then, I joined The Blues Project, he was in Paul Butterfield’s band. Two blues bands. And we both left the blues bands to start horn bands, which we were both kicked out of again. The horn bands that we started. Very amazing parallel in our careers. Starting from the day that we met. So, it seemed to me, in hindsight, looking at that, when I started producing at CBS, that we should make a record together. We were like destined to do something together. Now this whole time we had been friends since we met. I’d go visit him when I was in his town.

Well, Michael Bloomfield and I met on the ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ session. I had read about him in Sing Out Magazine, So, on that session he and I really hit it off. So, we played together on that date.

I was supposed to play guitar on that record. I packed up my guitar when I heard him warming up. It never occurred to me that somebody my age, and my religion could play the guitar like that. That was only reserved for other people. It never even occurred to me that that was an option for someone my age and my color. I had never seen that, or heard that up to that day.

Q: I think the star, or maybe the secret sauce of the Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde sessions was Paul Griffin. I know he was on some records by Garnet Mimms and on Chuck Jackson’s “Any Day Now.”

A: Oh...man…A big influence on me as well! Paul Griffin came from the Baptist church. On Highway 61 Revisited we did the tracks to ‘Tombstone Blues’ and ‘Queen Jane Approximately’ in one day.

The best thing I can say about Paul Griffin is take five minutes out of your busy day and get a time where you have nothing to bother you at all. Find a real nice stereo system and sit back and put on ‘One of Us Must Know’ from Blonde On Blonde. And just listen to the piano…And tell me if you can find on a rock ‘n’ roll record anybody playing better than that. And I would really like to hear what your decision is. To me it is the greatest piano achievement in the history of rock ‘n’ roll. I don’t hear anything than him playing the piano when I hear that record. And I’m thrilled that I’m playing organ but I’m embarrassed. And I think that Dylan should be embarrassed too. ‘Cause Paul just steals that fuckin’ record. It’s the most incredible piano playing I’ve heard in my life. If you’re a piano player try playing that note for note. It’s just incredible.

I played the organ on ‘Like A Rolling Stone.’ Paul Griffin on piano was so brilliant. He plays amazing things. And the thing that is really eye-opening about it, are the drums. Bobby Gregg, who had a hit record with ‘The Jam.’ Besides Michael’s playing, you can really hear the drums of Bobby.

Q: Bob Dylan has a unique approach to playing the piano.

A: No one talks about his piano playing because they don’t know. Bob had a very unusual way of playing in that he didn’t use his pinkies. So, both his pinkies were up in the air when he played the piano. And very interesting to me. It was very interesting looking to watch that. I used to really kick a kick of that.

Q: Why does the Blonde On Blonde album hold up so well and why am I still asking you questions about it?

A: There are a few reasons. The main reason is the chemistry of the participants. That’s the main reason. And the other reason would be the songwriting. I think the combination of those two things could make if they were as wonderful as those two were on that record it could make any record last a long time. The credit has to go to (producer) Bob Johnston. It was his idea. He had tried to get Dylan to record in Nashville in late 1965. He knew about the chemistry. And I also think he felt more comfortable there because he lived there. And he knew all the musicians intimately.

Q: Let’s talk more about Blonde On Blonde. Had your own organ work changed or gotten better from the time of Highway 61 Revisited to Blonde On Blonde?

A: Because in New York, where I was raised, all the sessions I played on and everything, it was three songs in three hours. I had never seen what they did in Nashville. They just hired the musicians and they were booked until we were done that day, or night, or whenever it was. They didn’t have any other distractions. There were no breaks, just whatever it was and I had never worked like that in the studio, but it was a big eye opener for me. During the day, Bob had a piano in his room and I would go up to his room and he would teach me the song and because there were no cassette machines in those days. I would play the song over and over for him and he would write the lyrics.

Yes. I was blown away by the whole thing. Just the concept of ‘hey, we can spend more than one hour on a song.’ This is great. This is gonna sound so much better than Highway 61 Revisited.

Q: What was really astounding about this gig?

A: (Laughs). I was astounded by everything. (laughs). I was astounded by the musicians. I mean, astounded by the musicians. Do you know at one point in ‘Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine,’ Dylan refused to overdub things. He just wanted to play it live right there, and forget about the fact that you could overdub. OK. I said to Bob, ‘horns would be really nice on this.’ (imitates marching horn line). And he said, ‘well…There’s no horns here.’ So, Charlie McCoy says, ‘I play trumpet.’ So, Bob said, ‘I don’t want to overdub anything.’ So, Charlie said. ‘I can play the bass and the trumpet at the same time.’ And Bob and I looked at each other, and Bob was laughing, and Charlie said, ‘no really, I can.’ He played the bass and the trumpet at the same time. Bob stopped singing, and I stopped playing, our jaws hit the floor. We were so floored by it. Bob was so floored by it he let it go.

Q. Did you know you were recording songs with a long shelf life? Did you feel his material would make impact and travel to another century?

A. I learned it after I did Highway 61 Revisited. So that one time during Blonde On Blonde I started thinking, ‘You know, where ever my hands move next it’s gonna be around for all time.’ I started thinking like that and I said to myself ‘Will you please shut up and just do what you do.’

It can completely freak you out if you thought like that. And I had that thought for one second, and then I said, ‘I really can’t think like this and do this job.’

So, yeah, but not on Highway 61 Revisited but on Blonde On Blonde I did have that thought.

The other thing was, by then, we were friends. We had spent a lot of time together. Off hour time together. Just sitting around bars and shit like that. Going to the movies and all this kind of stuff, so it was a much more comfortable situation and Robbie Robertson came to. Robbie and I split a room together at Roger Miller’s King of The Road Motel. So, Bob brought Robbie and I for his comfort level, rather than just go in there cold. You know what I mean?

Q: You recorded a song Smokey Robinson wrote and produced for the Temptations, “Get Ready.”

A: I’ve cut probably three other Smokey tunes over my career. He’s special.

One of my favorite things is that when I telephoned Dylan one day, and said, “Hey…What are you doing?” He immediately replied, “Eating a piece of toast and listening to Smokey Robinson...”

Q: How did you get the idea or concept of putting brass instruments in to rock and roll that gave us Blood, Sweat & Tears? Was it during the Maynard Ferguson on Roulette Records period that blew your mind?

A: Yeah. That was an immediate transference. I just said, ‘man, would I love to have a band that could, and I remember the exact words, that could put dents in your shirt from 15 yards.’

They just blew…It was just the most amazing thing I ever saw. It wasn’t like Count Basie or Duke Ellington. It was like modern…almost rock ‘n’ roll. It was fantastic. It was an incredible experience. I was sort of like a groupie. I knew some of the guys in the band and they treated me nicely. I was only about 15 and it was just fantastic. I turned 20 when it was over and Maynard left the country. So, I spent from 1959 to 1964 really every time they were in the area of New York I went to the gig. I hung out. I was friends with the drummer. People were nice to me.

In New York in those years Birdland was a big deal and one of the great things about Birdland was the best seats in the place were for underage people. They were just to the left side of the stage. And they were the best seats in the house. So, you had to be 18 to drink, but somehow, probably because the mob owned it, you could go in anytime. They let underage people in which was fantastic anyway, just in principal, but not only could you come in but you had the best seats in the place. So, that was not wasted on me.

Q. You met bass player Jim Fielder at the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival, who was playing with Buffalo Springfield at that event and invited him to be in Blood, Sweat & Tears. You appear in a solo performance on the Monterey International Pop Festival DVD set. You were at the festival as assistant stage manager.

A: It’s a terrible performance but my friends told me I looked so good that I let them use it. (laughs). It was a jam session with no rehearsal that they let me have on a Saturday afternoon. I was the assistant stage manager, and I asked if I could have a little set on Saturday and they said OK. So, I got friends of mine from other bands and said “Let’s just play this,” and we talked about it backstage. 3 songs. It was keeping in the spirit of the festival.

When I was setting up (Jimi) Hendrix for sound check I knew who he was. Before even reading the English music magazines about him, he played in New York with John Hammond Jr’s backing band at the Café Wha! It was the first time I heard him live. And you could tell then he was pretty special. Then, the guy who I was signed to as a writer, Aaron Shroeder, he signed Randy Newman, Gene Pitney, myself, Barry White and Jimi Hendrix for publishing before there was a record out on him.

So, when Are You Experienced? came out in England I got a copy way before anybody. Aaron had the United States publishing for his company. At Monterey ’67 I was totally conversant with that album which was just coming out in America then. And Jimi knew who I was so when we met it was quite nice. So, he said “I’m gonna play ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ tonight, do you want to play with me?” I said I would love to play with you and in the future I will. But I think it’s inappropriate to do it here because I’m working. Another of my great career moves…(laughs).

I was the assistant stage manager at the festival. Two things came out of Monterey. Jim Fielder. I knew him because of Tim Buckley and Mothers of Invention. These are things that first took place in New York. When I went out to L.A., I was looking for musicians for my new band. I bumped into him and ran it by him. He procured a drummer, Sandy Konikoff, and we played together.

Directly after Monterey, I went to the Big Sur Folk Festival on the grounds of the Esalen Institute and played with Sandy and Jim. We performed some of my new songs—“I Can’t Quit Her” and “My Days Are Numbered.” Then, the Blood, Sweat and Tears album, Child Is the Father to the Man.I came to Columbia Records in 1967, after the June Monterey International Pop Festival. I assembled BS&T and joined the label as a staff producer. I single-handedly brought BS&T to Columbia.

I knew what was happening in 1968 with John Simon producing the debut Band album and should have had an early glimpse of what was going on. But at the time I was staying home and not going out. And John would call me over and over again and say, ‘You gotta come hear Robbie’s record.’ That’s what he called it. And I didn’t know what it was. And then I heard it when it was done at Albert Grossman’s office. I went, ‘Holy shit! This is ridiculous. I didn’t think it was gonna be like that.’

I had no idea what that was gonna be like. Up at Albert’s office they just played it. Side one and side two. And I kicked myself for not going to the sessions since I was invited to those sessions. John Simon went from doing the Blood, Sweat & Tears album to doing that record. One after the other.

John did a lot of engineering at Columbia before he became a producer. I watched him like a hawk. I put him right up there with George Martin. Jerry Ragovoy and Phil Spector. I didn’t see him do much engineering. Fred Catero was the engineer on the BS&T album. And he was pretty fuckin’ amazing. I had never been in a situation like that where it was a project I was involved with. The engineer was great and the producer was great. And all the problems that I brought into the project he solved. I had alienated the rest of the band.

I had known Robbie, worked with him on Blonde on Blonde, we got close together, but lost him for a while. At the Brill Building where I was at a lot, Robbie was up there but in the shadow of Ronnie Hawkins. Aaron Schroeder was my music publisher. I worked for him. Robbie did some things with him.

The Band Big Pink album was done in New York at Bell Sound. As a session guy I worked there. I would go there with Jerry Ragovoy. I was not entranced by the room it was usually who was in it that killed me. I thought Mira Sound was great. A great room. I did a lot of session work there.

Q: After you heard the Music From Big Pink album, did you have any concerns that they couldn’t pull it off live?

A: I already knew what I was going to see. I had played live in 1965 with Robbie and Dylan. The Hollywood Bowl and Forrest Hills in New York.

The Hollywood Bowl show was the only place where Bob played where he wasn’t booed. How ‘bout that?

I never knew anyone like Garth Hudson as a person. I never knew anybody like that as a musician. We didn’t really jell like the other guys.

In 1966 I got the itinerary for the Dylan tour and I said to myself ‘I can’t do this.’ They were playing Dallas, Texas. 2 years after JFK. I said to anybody who would listen, except Bob, of course, ‘You’re going to fuckin’ Dallas. I don’t want to be the John Connely of rock.’ That was my line (laughs). I thought I’d be sitting in the fuckin’ front seat and I’ll get killed.

I saw The Band play live very early.

Q: In 1969 you did the musical score for director Hal Ashby’s first film, The Landlord. I love “Brand New Day” sung in the movie by the Staple Singers. (Ashby directed other films with folk, rock and pop songs in them: Bound for Glory, Harold & Maude, Shampoo, Coming Home, and the Rolling Stones’ Let’s Spend The Night Together concert film.)

A: He was an interesting guy. The thing that I loved about Hal is that I never met anyone like him. He was one of a kind person. One night when we were doing the film The Landlord, I got front row tickets for a Band concert at the Long Beach (Ca.) Arena. I couldn’t get there or didn’t know how to get there. So, I said ‘Hal I have two tickets to see The Band tonight and if you drive. You are the other ticket.’ And he said, ‘Oh yeah. I’m there. What time? Let’s go!’ So, he had an Italian sports car, a Ferrari, convertible; top down, smoking joints, he smoked pot incessantly, and we got there. We saw the show, enjoyed the concert, and went backstage. Said hello to everybody.

At the show I met Mac Rebennack (Doctor John) who sat next to me. And Hal parked the car illegally. ‘Are you OK with that?’ ‘Not a problem.’ So, when we came out, I hoped the car would be there. He starts to smoke a joint as we are walking to the car. Cops are all over the place and we’re parked illegally. ‘Hal, there’s a lot of cops around us with the show breakin’ and everything.’

I pointed to one on the street in front of us. Do you think it’s smart to smoke a joint? This is back in 1969. And he said, with a lungful of smoke exhaling, ‘Well, what’s the worst that can happen? They’ll arrest us and beat the shit out of us.’ And he kept smoking a joint. We got home. I loved that attitude. Of course I can’t be there. I’m the antithesis of that. I’m the opposite of that and somehow, we got along.

Q: In 1968, Super Session revealed the collective musical talents of you, Michael Bloomfield, after his Electric Flag endeavor, and Stephen Stills, immediately after Buffalo Springfield played its final gig. Before it was reissued, the album had sold 450,000 copies from a $13,000.00 recording budget. Super Session reached number 11 in Billboard, and I know a lot of musicians learned plenty from that epic album.

Q: Michael Bloomfield ended my guitar playing I’m tellin’ ya. Both of us had just played on that Grape Jam’ album. So that sort of gave me the inspiration to say, ‘why don’t we make a record.’ I wanted to make a record with Bloomfield, and I wanted to make a record that was a very simple, basic record, not a ‘weighty’ record. So inspired by the Grape Jam thing, I said ‘let’s make a rock ‘n’ roll record based on the way jazz records are made. You pick a leader, or two leaders, and then you just go in, you pick some songs, you pick sidemen, and you just blow. No rehearsing or anything. You just go in and blow.’ So, I said ‘I don’t want to make a jazz record.’ And I was very dissatisfied with the way he was recorded up to that point.

I mean that his live playing was like 300 times better than performance on a record to that point. In my opinion. So, what I wanted to do was put him in a situation where he was uncluttered by his career, and uncluttered by his situation in the recording studio, which must have inhibited him. So, I made it as uncomplicated as possible for him. Because that was the goal of the sessions for me, was to get amazing playing out of him like I heard him do on stage. And I felt really vindicated that I had done that. And that’s what I wanted. I did what I set out to do. And, the other thing was, we both had been kicked out of the bands, and then Stills, too. He was out of his band Buffalo Springfield.

So, Stills fit in, in a really weird way. Because none of us had anything at stake, and that was the whole point of that record. There was no career thing goin’ on. We just did it because we played music. That’s what’s so wonderful about that. Super Session wasn’t made to sell records. It was just made like those jazz records were made for Blue Note, except it wasn’t ‘Blue Note’ kind of music. It was more music that we were in to. ‘Albert’s Shuffle’ is sort of the hit of that side, as time has passed. Although, the song was used twice in the film Sneakers, by Robert Redford. That floored me.

Q: Did Super Session creep on to FM radio or explode on the dial in the late ‘60s?

A: Well, see, I had no expectations for that record. I mean just none whatsoever. I just did it because I had a job as a producer and I had no one to produce, and I went in because I thought Michael and I should make a record together, because how our careers were parallel. And also, because we were friends, and it would be fun to work together.

Michael brought Eddie Hoh (drummer) in, and I brought Harvey in (bass). I said, ‘you pick the drummer, I’ll pick the bass player.’ Again, sort of like a Blue Note concept.

The most important thing is the playing of the two principals, Bloomfield and Stills. It’s timeless. Bloomfield’ stuff is some of the greatest blues playing that there ever was. And it was a non-vocal Stephen Stills, owing to contractual limitations and restrictions. Which was a very strong thing in that decision. I regretted that a lot that night. But I said if he sings, we’ll never be able to put this out.

I knew Stephen was a great guitar player and that was the key thing. But I had to take a lot of shit from David Crosby when that came out. ‘Why the fuck didn’t you let him sing?’ And I told him and he didn’t even listen to me.

Because it was a great period of time and there were great minds working geographically located in the same place. There was a lot of freedom out on the west Coast, but frankly, Super Session could have been recorded anywhere.

Q: In 1997, The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper came outon CD, it was a late ‘68 live date taped at the Fillmore West on the heels your Super Session studio outing. Skip Prokop and bassist John Kahn. Carlos Santana and Elvin Bishop also appear on the recording.

Digital downloading music pioneer and guitar player David Kessel, a son of master guitarist and jazz icon, Barney Kessel, first discovered the Super Session LP in early summer 1968. David also plays harmonica and flute. We recently listened to live Super Session recording. We both dig your covers of Albert King’s “Don’t Throw Your Love on Me So Strong” and “Mary Ann” that Ray Charles cut.

A: The Blues Project song I wrote ‘Flute Thing’ was basically a cadenza Barney Kessel played at the end of a song in the 50's on the Contemporary label that I learned as a fledgling guitarist. I NEVER forgot where it came from.

Well, you know, that was a weird record. We sort of did that because people gave us some shit about the confines of the studio, and it was slick, this kind of thing. So, I said, ‘let’s go down and dirty and play a gig and record it live. Nobody is gonna yell studio at us for that.’ So that’s what we did. And it actually was a little too down and dirty.”

Q: You recorded tracks with the Rolling Stones in 1969.

A: I saw the Rolling Stones American debut in June of 1964 at Carnegie Hall. It was hard to hear them because of the fuckin’ women going berserk. Different from the Beatles. And I caught them on The Ed Sullivan Show. I later knew Brian Jones from the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival where I was the assistant stage manager.

After I completed The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield & Al Kooper, I went to London and I was picked up at the airport by my good friend Denny Cordell. He then said, ‘the Stones’ office called me and asked if I felt like playing on a few recording sessions with them. They want you to play on some sessions.’

I said, ‘How did they know I was gonna be in England?’ And Denny replied, ‘I didn’t say a fuckin’ word. And I don’t even know how they figured out I was involved. But they called me for Tuesday and Wednesday night at Olympic studios.’

The next day we left the hotel and went shopping on Kings Road and ran into Brian Jones in a shirt store who asked, ‘Are you gonna play the session, Al?’ I could never say no to these people. So, I went. The main reason they wanted me was that Nicky Hopkins, their regular keyboardist was in the United States.

I went to the studio. Bill and Charlie were there. I met them before with Bob Dylan. I sat at the organ and met Jimmy Miller, the producer. Mick and Keith bolted through the door. Mick wore a gorilla coat and Keith a hat with a long feather. Everyone sat around and they passed out acoustic guitars to anyone who could play acoustic guitar. Then Mick and Keith played acoustic guitar ran down the tune for everybody with the chord changes and the rhythm accents. There was a conga player in the room who rolled hash joints. It was decided that I would play piano on the basic track and later do an organ overdub.

I got a groove going which I heard on an Etta James cover version of ‘I Got You Babe’ that worked. It had nothing to do with Sonny & Cher. I could not believe the Etta version. I heard it on the radio and thought it was unbelievable. I wanted to own it and bought it. They played the song in the studio to learn

Keith picked up on it with a guitar part that meshed with my organ part. Jimmy Miller showed Charlie an accent and he just couldn’t get the part. Jimmy sat down at the drums and stayed there and played on the take. Charlie was unhappy but he hid it completely. Very graceful. He didn’t throw a temper tantrum but said ‘why don’t you just play the drums?’ He said it sincerely. He didn’t say it like I would have. (laughs). Bill played bass, I played piano. Mick and Keith played acoustic guitars. Keith then did a lead electric guitar part and I overdubbed the Hammond organ. We were out there together. Brian Jones was in the corner on the floor reading a magazine.

The recording went on for about four hours. Then all sorts of food arrived later in the night: Racks of lamb, salads, wines. Not a cheeseburger break, like back in the States.

I told Mick that if he ever wanted to have horns on the record to call me. Over a half a year later an eight-track master tape showed up at my office at CBS Records. The note said ‘Dear Al, you once mentioned you could put some great horn parts on this. Well, go ahead and do it and send us the tape back. Love, Mick.’

They were working on an album, and the record had an intro on it that we didn’t do. That was a separate piece that they tacked on to the front. I wrote a horn chart and hired a horn section and left a spot in the intro for a French horn solo. I was coached by Ray Alonge. I sent the tape back to Mick. Around a year later it came out without all the horn parts except the French horn at the intro. I think they really liked what I did and gave me credit. But I failed at what I set out to do which was putting horns on it like the Etta James record. I thought it was really great and I was able to play, what I think is some of my best playing I ever did in retrospect.

The next night Mick and Keith picked me up at the hotel, they were in the lobby, and we cut a track for Performance, the film Jagger was working on. It’s not the version in the movie or soundtrack. I played guitar.

A little later, 1971, when they were working on Sticky Fingers, there was a birthday party for Keith at Olympic and I was invited and went. They cleared the room and set up to record. George Harrison was there and he declined to play. Eric Clapton, myself and Bobby Keys joined. I thought the song was great. They might already have cut it on the ’69 U.S. tour. This was a completely different take.

That was the night I met George. He was very nice. Over a period of time, I spent a lot of time with him. at 11:00 pm one night the doorbell rings and I wondered who the fuck this is? And I look at the curtain and it’s George. I never gave him my address. And I opened the door and said ‘there’s a Beatle at my door!”

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015's Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016's Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017's 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 they wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll TV Scenes) will be published in mid-February 2026 by BearManor Media.

Harvey spoke at the special hearings in 2006 initiated by the Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation.

In 2017, he appeared at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in its Distinguished Speakers Series and as a panelist discussing the forty-fifth anniversary of The Last Waltz at the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles in 2023).

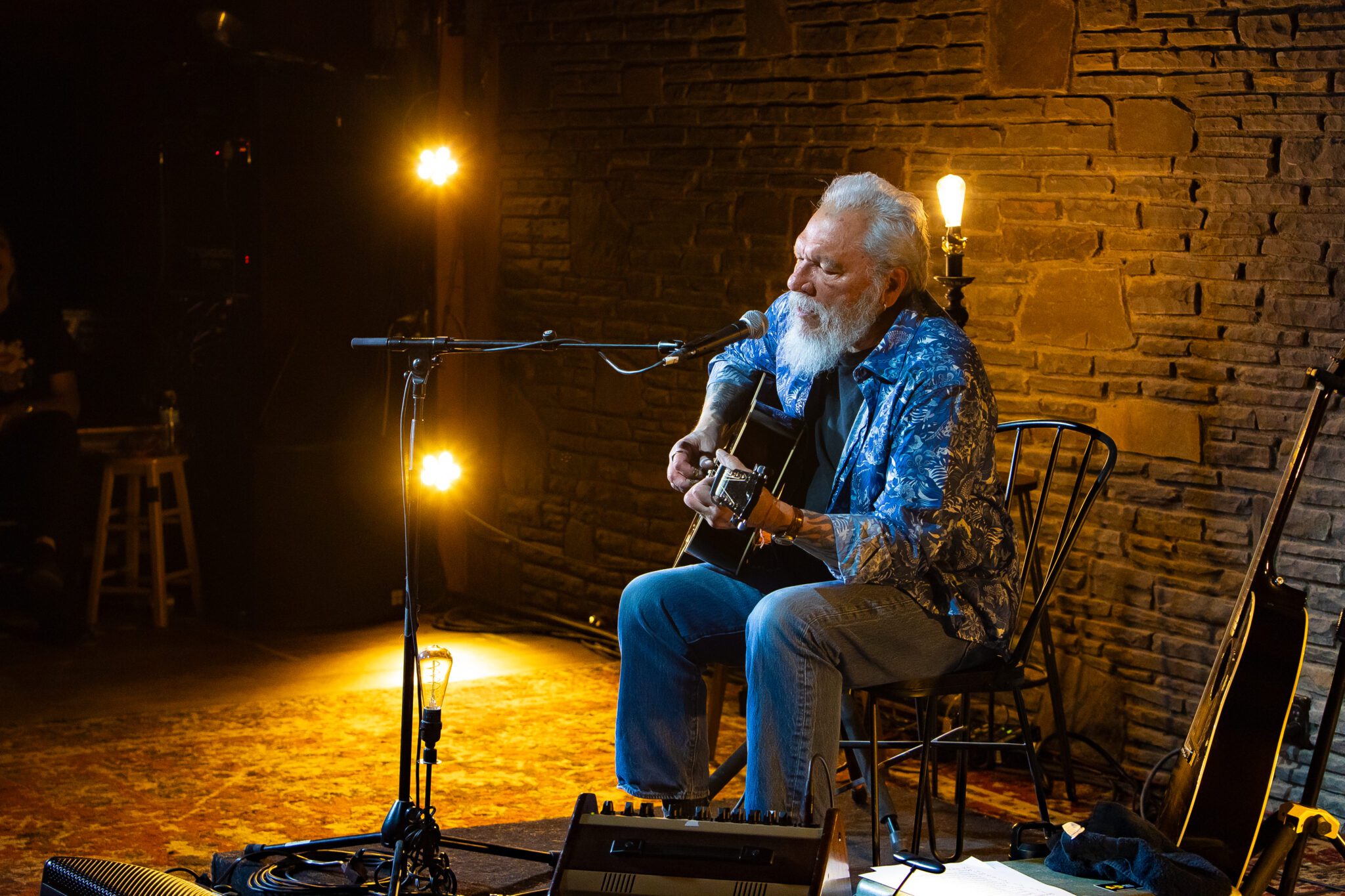

Photo credit Roz Levin © Sony Music Entertainment