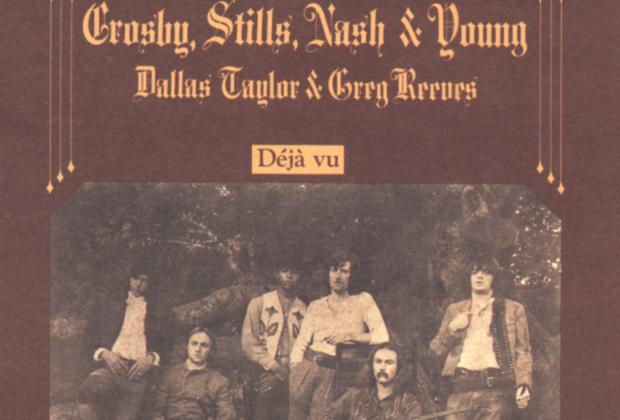

50 years ago this past spring Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young released their debut LP Déjà Vu.

Although perceived as a group effort, nine out of Déjà Vu’s 10 songs (the exception being “Woodstock”) were actually recorded as individual sessions, with the other members chiming in as agreed upon, but however it came together, it proved to be a Top Ten smash.

Rhino/Warner Music Group is preparing a 50th anniversary edition for retail outlets last quarter of 2020.

The story of CSN&Y - their "creation myth" - is as fabled as John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s Quarrymen debut, as Mick Jagger and Keith Richards serendipitous encounter at the Dartford train station.

The Crosby, Stills & Nash, Déjà Vu and the live recording, 4 Way Street, have cemented their sound and sensibility into icon status, rock legends for all time.

Equally legendary were their endless squabbles - more breakups and reunions than Liz and Dick - their squalid pharmaceutical excesses, their incredulous capacity for regeneration to the surprise and delight of at least three generations of fans.

And now, fifty unimaginable years later they still carry on, at least with a new configuration of Déjà Vu.

Those cherished harmonies however creaky, continuing to hold sway over anyone who ever sought solace in the melding of voices. They have traversed the longest and windiest of roads - more like a gauntlet - having shared delirious highs and searing lows. You can hear it all on Déjà Vu.

“It was a different band when Neil joined,” Graham Nash explained to me in a 2014 interview we conducted for Southern California’s Record Collector News.

“Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young are a completely different band than CS&N. And not a lot of people understand that. They think it’s just an added voice. But it’s not. It’s an added attitude. Neil brings a sharper edge. I was gonna say a darker feeling but I don‘t mean that in a negative way. He brings this edge to us that we don’t have. And, of course, you have to take into account his ability to play lead guitar against and with Stephen.”

“When Neil joins the CSN faculty, a whole other wild card element enters the building,” suggests poet and rockademic Dr. James Cushing, a former deejay on KEBF-FM in Northern California.

“‘Cause he has such a distinctive sound and such a strong personality that he makes his mark on all the other people who are there. But yet Neil’s own work somehow fits in while being instantly recognizable.”

Just before Neil Young joined the CS&N, right after their disc was engineered by Bill Halverson at Wally Heider studios in Hollywood, seventeen year old musician Richard Bosworth in Bridgeport, Connecticut first learned the news directly from Stephen Stills about Young enlisting as an equal band member to the trio.

In a 2015 interview, Bosworth, now a respected studio engineer and producer, in 2020 he was at the helm of Johnny Rivers sessions at Capitol Records studio in Hollywood, described a very memorable 1969 experience.

“As 1968 turned to 1969 I was seventeen years old and in my senior year of high school. I'd played guitar, bass guitar and keyboards in several bands. 1968/1969 were the peak years for the band Jennifer’s Friends. We released four singles on Buddah Records and one ‘Land of Make Believe,’ written by Harry Vanda and George Young of the Easybeats, got some radio airplay in the mid-west.

“On Friday May 2, 1969, on our way home from a gig in Bridgeport Connecticut we stopped by The Stone Balloon, a new music club underneath Pegnataro's Super Market in downtown New Haven to firm up a gig for the following week.

“The Stone Balloon was open little more than a year in 1968/1969 but an amazing number of rock, blues, jazz, folk and soul acts that were about to break performed a Thursday thru Sunday two show a night engagement. Jethro Tull, Joni Mitchell, J. Giles Band, B.B. King, Albert King, Taj Mahal.

“Arriving there the booker walked us through the club to the dressing room while John Hammond Jr. was onstage performing. We were told we would be opening for Neil Young and that he had been lead guitarist for Buffalo Springfield. We were aware of the group as ‘For What's it's Worth’ had been a hit on the east coast and there had been article in Eye magazine with a photo of Stephen Stills stating that he was lead guitarist for Buffalo Springfield. None of us had heard of Neil Young. His name was actually mis-spelled on a poster for the engagement as ‘Neal Young!’

“The following Thursday May eighth the club manager said Neil and band were flying into Hartford from California and the plane was late and we might have to do two sets. There were only a dozen people in the audience while we did our first set. We took a break and backstage in the dressing room the club manager asked us to do another set as Neil still hadn't arrived. We were getting ready to perform again when the club manager came back to tell us they were here.

“A moment later Neil walked in. He had this glowing aura. Talent and greatness just seemed to be pouring off of him. I hadn't heard a note of his music, but I just felt an overwhelming certainty that this guy was going to be as significant as The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. He said hello to everyone, was very warm and friendly. The band filtered in behind him, one blond and two dark swarthy guys, all real quiet. Neil was talkative, taking out his guitars and letting us check them out. He handed me his orange Gretsch 6120 which I strummed on for a moment, not knowing that it was his primary guitar in Buffalo Springfield.

“At one point he asked a couple of us if we thought it would be cool to do a few songs acoustically before bringing up the band. I remember thinking it was an odd idea as it was all about bands in those days. Neil was so nice though, we were encouraging about it. He went outside the club by himself for about ten minutes before he went on. That seemed different, like he took it seriously and would want some solitary time to psyche himself up to perform.

“He went on with his Martin D-28 guitar and opened up with ‘On The Way Home’ from the last Springfield album. Playing songs acoustically suddenly seemed like a brilliant idea. Neil had a very stoned stage persona, unlike how he had been backstage. He did several songs from what I later learned were on his first solo album. He was engaging with the small audience, asking for requests.

“Someone called for ‘Last Trip To Tulsa’ and Neil laughed and said ‘Aw that's too long, I think I only ever played that once when it was recorded.’ There was a request for ‘For What It's Worth’ and he laughed again. ‘No man, I can't do that one, I only know how to play my guitar part on that.’ He took a break after playing six songs and then he and his band and a crew person set up for the electric stuff. It took a long time, they were not just going to plug in and start playing.

“They worked on individual sounds of instruments, checked vocal mic's carefully. Really meticulous. Neil had a old black Les Paul with a bigsby vibrato bar. The other guitarist was playing Neil's Gretsch 6120. The guitar amps were all old Fender tweeds and blonde Fender Bassmans, unlike the Marshall amps of the day. Finally they seemed to be ready and everyone left the stage for the dressing room.

“A moment later Neil walked out to applause from the audience and said to the room at large, ‘No, not yet’ and went outside the club by himself again for another ten minutes or so. The first song was ‘Cinnamon Girl.’ Neil's guitar sound had this ultra-distortion. Super loud and stunning.

“He introduced the band as Crazy Horse and told us they would be playing songs from a new album they had just recorded Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere and launched into that title track. Before the next song Neil introduced guitarist Danny Whitten, stating that he'd heard Danny writing a song and it was good so he felt he better get in on a good thing and co-write it. They tore into ‘Downtown,’ then ‘Down By the River’ with the three part harmony vocals on the chorus and Neil's single note machine gun guitar riff, the extended solo sections. ‘The Losing End’ was the penultimate song of the set.

“After our second show set it was decided that since there were only about seven paying customers in the place on that late Thursday night, Neil would just do an acoustic set to end the evening, He did his usual walk outside by himself before performing. Crazy Horse and our group were sitting out in the audience and after playing five songs or so Neil says to Crazy Horse ‘Hey, I can tell you guys want to play, don't you?’ Neil said ‘Well what do you want to play?’ In unison they replied ‘Down By The River’ which they performed to end the evening.

“The next morning at school I told my musically inclined friends about Neil Young, strongly suggesting that they check him out. Some would be there that evening although a few had tickets to the Jeff Beck Group concert at nearby Yale's Woolsey Hall. All through the day songs from the soon to be released Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere album were running through my mind. Attendance was better at Friday night’s shows.

“After our first show set Neil began acoustically and again exhibited a humorous and stoned persona. He told a few funny stories, thanked the audience for coming to his show instead of the Jeff Beck concert mentioning that he was a big fan of Beck.

“Neil at one point was strumming a guitar by himself while a friend and I were having a discussion about our imminent senior graduation dinner the following month. Neil said ‘What are you guys talking about?’ I explained it was my responsibility to book a band for the event. He asked ‘What does it pay?’ I replied ‘$250.00.’ He went ‘Um. That's what I'm getting a night for this gig. Maybe I'll play your senior grad dinner.’

“By the time of Saturdays shows word had gotten out around town that Neil Young and Crazy Horse were happening and The Stone Balloon was packed that night. We did our usual alternating sets with Neil solo followed by him and the band.

“Suddenly Sunday night Stephen Stills shows up. He was with a dark haired guy who turned out to be Dallas Taylor. Backstage between shows Stills was cocky and confident. He and Neil seemed happy to see each other.

“I asked Stephen what he was doing now after Buffalo Springfield. ‘I've just recorded a new album with David Crosby of the Byrds and Graham Nash of the Hollies but we don't know what we're going to call it’ was his reply.

“Stills told Neil he had just been at dinner with Ahmet Ertegun of Atlantic Records and Ahmet told him about Neil's New Haven gigs, suggesting Stephan drop by to talk. We all know now what Ahmet wanted those two to talk about.

“At the end of Neil Young and Crazy Horse's final set of the four day engagement Neil brought up Stills and Dallas Taylor took over the drums. To end the evening Stills and Young proceeded to trade fiery guitar licks like they had in Buffalo Springfield and soon would again in some new unnamed group in the future.

“Monday morning, back at school, I was still thrilled by the entire previous four days of shows. I was absolutely certain that in Neil Young, I had met and experienced someone who was going to be a major star. Stephen Stills also gave off that vibe. I'd never run across anyone who had the charisma, talent and greatness that emanated from Neil.

“In May of 1969 virtually no one knew of Neil Young or Stephen Stills.

“By the end of August of 1969 at the Woodstock Music and Arts Festival, which I attended, one of the headliners Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young were considered to be the American Beatles.”

“After the June 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival I later got the (soundtrack) rights to Woodstock,” record producer and former Atlantic Records executive Jerry Wexler told me in a 2007 interview displayed on cavehollywood.com

“The soundtrack albums came out on Atlantic on our Cotillion label. There was a lawyer named Paul Marshall, he used to be our in-house council. But we parted ways. And he was not our lawyer anymore, but, nevertheless, he called me up, ‘Listen. Are you interested in Woodstock?’ It was going to take place in two weeks. Who the hell knew what Woodstock was going to be? He said I could have the rights for seven thousand dollars. I thought about, and bought it for seven grand. I figured seven grand? Let me take a shot. And that was it. I should have grabbed the film rights to but Warners got them and thank God that I bought Woodstock.”

On August 18, 1969, CSNY played the Woodstock Music and Arts Festival, only their third live show together.

“Woodstock…The rain, and the mud, and the getting together of a half a million people that thought the same way that we did,” remembered Nash in a 2007 conversation we had for MOJO.

“Hanging out backstage in John Sebastian’s tent after landing in the helicopter that had a couple of problems. Getting into the tent and of course John [Sebastian] breaking out his best stash. And then realizing that nobody there has ever seen our band. And this is the Grateful Dead, The Band, Ritchie Havens, John Sebastian, Santana. None of them had ever seen us. They loved the record and they were all going, ‘well, you know, fuckin’ show us.’ ‘Shit or get off.’”

Neil Young performed songs like “Mr. Soul” and “On the Way Home” for the massed gathering, but he was not to be glimpsed in the Michael Wadleigh-directed Woodstock film documentary which was screened theatrically in 1970. Having felt distracted by the omnipresent cameras and only wanting to play for the throng, Young didn’t sign the artist release form for movie exhibition.

Although Neil declined to be in Woodstock, his song “Sea of Madness” was included on the very lucrative soundtrack album—the product that changed the retail record and youth culture business forever.

Strangely, though, the version that was chosen for the package was actually taped at a CSNY Fillmore East show a month after the festival.

“I could never figure out why Neil didn’t want to be a part of the Woodstock film,” mused Nash.

I wanted to know about “Sea of Madness” and the inclusion of it in CSN&Y’s 1969-1970 repertoire.

“(Neil’s) ‘Sea of Madness’ organ kicked into the band. And all of that was pretty spontaneous. And none of this was calculated. And that’s one of the things that have been so fascinating about this band is that there is very little planned.

“The song is planned,” he reinforced, “the way we’re gonna do it is up for grabs, and the way it’s gonna get played is up for grabs. But we’ve always been smart enough to realize that in that search in that scent of discovery of what it is about what we’re about to do we don’t bring too much to the equation. We have a song, we know we can play it, we know how it’s going to basically go and the rest is up for grabs. And that’s been one of the great musical things about CS&N and CSN&Y.”

Nash talked about CS&N’s epic debut LP and his first encounter with Neil Young.

“There were no formal rehearsals before we went into the studio. Our rehearsals consisted of private going through the tune, and then saying, ‘let’s go to (Peter) Fonda’s house! Let’s go to Paul Rothchild’s house! Let’s go to Alan Pariser’s house! Let’s go and sing them this shit!’ Eventually we could sing that entire album on a couple of acoustic guitars and blow people’s minds.

“When I first went in to Wally Heider’s studio on Cahuenga in Hollywood to record with engineer Bill Halverson, I thought it was small and it was funky. I never met Bill Halverson. We got in Crosby’s Volkswagen van and drove up to the studio and brought our guitars and amps out and started to make the records.

“We knew that we had fabulous songs. I would never play anybody a song if I didn’t feel two things: One that it got past me. And two and I would hope that it would be interesting for you to hear. So I have those two criteria whenever I’m writing. First of all it has to get past me. I have to figure out whether the song has to resonate, has a reason for existing, and after that, do I want to put this on to somebody else? And the answer to those two questions is yes then you’ll get to hear the song. Cass sings on ‘Pre-Road Dawns.’ We found a spot for her to join on us a vocal.

“This album kind of made itself. We had the songs. We had the energy. We were happy as fuck. All of us, Stephen was going out with Judy (Collins). I was with Joni (Mitchell), and David was with Christine. (Hinton). How better could life be? And Crosby had a lot to do with the best herb,” laughed Nash.

“When we finished the album we realized that we would have to go out and play live,” ventured Nash. “We knew it was going to be a hit when we walked out of the studio and gave the two-track to Ahmet Ertegun. And I have a photograph of David and Stephen outside the studio with Ahmet at that very moment. We knew it was going to be a smash. We just knew. Ahmet got it immediately.

“He listened to that music and said, ‘Ah fuck…I want it.’ So they worked it out between [David] Geffen and Ahmet. I was on Epic, Columbia wanted Poco, and there was a trade and we all ended up with Ahmet, for which we were incredibly glad.

“But we realized we would have to go out and play live. OK. So, we’re talking about this. And, Stephen says, ‘Man, I really need to spark off somebody. You and David are pretty good rhythm guitar players but man, I wish we had another…Somebody, maybe an organ player that I can jam with and solo.

“We talked with Stevie Winwood. We talked with Van Dyke Parks. We needed somebody just to keep Stephen on his game and competitive and on fire. And I think basically that Stephen and Ahmet came up with the idea of or maybe it was Ahmet to Stephen, was getting Neil on board.

“I was the only one reluctant to bring Neil into the band. And the reason was that we had spent the last few months making this incredible record and developing this beautiful harmonic sound, right. But Neil wanted to be more than a musician for the road show. I can’t commit this. I know who Neil is.

“One of my favorite songs is ‘Expecting To Fly’ from Buffalo Springfield Again that he did with Jack Nitzsche. Listen to it. So I knew who Neil was and I loved this fucking song. I was a big fan of the Buffalo Springfield. How could you not? I listened to Buffalo Springfield. ‘On The Way Home.’ That’s a great one. ‘For What It’s Worth.’

“But I said ‘I can’t commit to this until I meet Neil. I gotta sit down with this cat. I wanna know who he is. I wanna know if I can go on the road with him. I wanna know if I want him to be a part of my life.’ And, that made sense to them.

“So, at a coffee shop on Bleeker Street in New York I went and had breakfast with Neil. After that breakfast I would have made him the President of Canada. He was incredibly funny. He had an incredibly dry sense of humor. He always had a bunch of songs that I loved, ‘Expecting To Fly’ being the primary example. And at the end of that breakfast and walked down to the Village Gate where we were rehearsing and I said, ‘OK.’

“It was obvious that this man was as serious as a heart attack about his music. It was obvious by hanging out with him that he was destined for great things. And it was obvious by hanging out with him that he could put a fire under Stephen that we needed. ‘Well, have you ever seen me and Stephen play together?’”

I mentioned to Nash that I heard when CSN&Y were rehearsing for their 1974 tour at Neil Young’s Broken Arrow ranch in Northern California he wanted “When You Dance I Can Really Love” from Young’s After The Gold Rush album in the set list.

“I wanted to open with that song! There’s lots of Neil Young songs I want to do. I want to do ‘Expecting to Fly.’ Are you kidding!

“I brought it up in the CSN&Y 2006 tour. ‘Can we do ‘Expecting To Fly?’ And he looked at me and said, ‘Ahhh. I don’t think you can sing the high part.’ And I thought, “You fuck! You know damn well that if I’m asking you to do it I have my fuckin’ part down.”

“I lived at Peter Tork’s house and Stephen would hang out a lot,” reminisced photographer Nurit Wilde who witnessed the 1969 lineup in rehearsals along with photographer Henry Diltz, who took the cover photo of the debut Crosby, Stills and Nash LP.

“Stephen had bought Peter’s house,” emphasized Nurit. “I met Graham Nash at Cass Elliott’s house. Lovely man. Then in 1969 Crosby, Stills and Nash make this great album. And I thought ‘what in God’s name are they doing now bringing Neil in?’

“I had seen a lot of tension in Buffalo Springfield. But maybe it helped the creative juices. To me the only way it made sense for Neil to join that band and because of his previous tension with Stephen, I think they were good foils for each other.”

“We rehearsed for our first tour on the Warner Bros set of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They in Burbank,” Graham confided to me. “So, it was pretty obvious from the sounds I was listening and the way that Neil was affecting Stephen that this would be a really great thing. The music got better on stage. Because we were actually doing it, and I didn’t know where it was gonna go after they started playing.

“When we started touring we used to start acoustic. We would begin with ‘Suite: Judy Blue Eyes’ and blow their minds. What would happen is that the curtains would open and there would be a line of Martins, and the drums and the bass. And then we’d say, ‘We’d like to introduce you to our friend, Neil Young.’ And the place would go fuckin’ bananas, right.”

In the last week of August 1969, my brother Kenneth and I sat up front at L.A.'s Greek Theater. We’re teenagers but even we recognize that this particular concert has a gravity that distinguishes it from previous rock 'n' roll shows we’ve attended, where little was at stake beyond experiencing a dizzying euphoria. This night's music insisted on our undivided attention, that we sit up and listen, really listen.

A beguiling young singer/songwriter from Canada strolled onstage. Accompanying herself on guitar, Joni Mitchell's unerring command of mood, of tempo, of temperament, her reverence for the deeply personal as a means to explore the universal, showcases a talent of a higher order. The audience was now suitably primed. She was followed by the headliners, fresh off a tumultuous success at Max Yasgur's upstate New York farm - Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.

What Ken and I recall most clearly were, of course, those exquisite vocal harmonies; the finely-wrought arrangements, all those gleaming guitars - acoustic and electric - lined up like a phalanx of artillery ready to rumble; Neil, sitting at a Hammond B-3, smearing chords while "Sea of Madness" crackled like thunder.

In 2020 I asked Ken what he recalled about this gig. In 1967 we saw Buffalo Springfield at the nearby Hollywood Bowl venue.

“An ocean of ink has washed ashore over the years detailing CSN&Y’[s sumptuous sound (early on), the prima donna antics (Persian carpets and private jets), the sordid behaviours (aka the ‘Frozen noses’) and the endless fits masquerading as artistic license.

“It’s an exhausting litany and yet there were moments of such incandescent beauty that the whole tawdry enterprise was not beyond redemption. Bootlegs from the earliest gigs in summer 1969-the Greek Theater and the Fillmore East in New York–document that ineffable, pitch-perfect rapport between voices and guitars in shimmering balance that toiled like church bells.”

Photographer Heather Harris was also in attendance at the Greek Theatre engagement.

“I sat far back in the bleachers with a borrowed telephoto lens to take a photo of CSN and their pal Y (for a few tunes) at the Greek Theatre in 1969. Joni Mitchell was the opening act. I so liked Buffalo Springfield and the Byrds that this was a much anticipated show.

“The harmonies were luscious but I wished even then that the material around it was a little more edgy. A whole set of ‘4 + 20,’ ‘Ohio’ or ‘Guinnevere’ (whom I had met at the Beverly Glen place of Crosby and deejay B. Mitchell Reed through one of her friends. She was amazingly worldly with hair past her derriere. Crosby's life would have been entirely different and positive had she not died in a car accident shortly thereafter) tempered material would have been more to my liking than ‘Marrakesh Express,’ ‘Our House’ ‘Lady Of The Island’ and so on....”

CSN&Y were booked for the Big Sur Folk Festival during September 13th-14th. In December 1969, CSN&Y did an early set of music near San Francisco at the well-chronicled Altamont free concert headlined by the Rolling Stones. The Grateful Dead didn’t play after being advertised with Santana, Jefferson Airplane and the Flying Burrito Brothers.

“It was very obvious from the very beginning that this was gonna be fucked,” stressed Nash. “First of all, getting in there. There was no way we could get into Altamunt. It was insane. So, my friend Leo Makota, who was our tour manager, hot-wired a car and him and us, and the lawyer, Melvin Belli, made it into Altamont. But it was fucked from the start. First of all, the music that they played between acts was electronic music.

“And we were only there for Jerry (Garcia). ‘Cause it was Jerry that called Crosby and said, ‘Hey man, we’re gonna do this Woodstock West, man, you gotta be a part of it. We’ll all be there, man.’ We played and not even sure how well we played. Maybe 45 minutes or something and we got the fuck out.

“That evening we did a gig [in Westwood] at UCLA at which Stephen collapsed. But I think the Pauley Pavilion show was pretty good, really.”

During the fall of 1969, CSNY navigated between the stage and the studio. They combined a US tour with the recording of their initial album as a quartet. Déjà Vu was eventually issued in 1970 on March 11th 1970. It soared to the top of the charts.

Déjà vu engineer Bill Halverson already had an established history with Atlantic Records. He was behind the dials for the Crosby, Stills & Nash album.

“I was a big band guy and a vocal group guy who was in love with the Four Freshman and Hi Los, which really served me helping the Beach Boys and set me up for Crosby, Stills and Nash,” enthused Halverson in a 2007 interview we conducted.

“By 1969 I had done to this point a lot of sessions but not a full album. So, I asked the person at the booking office if I could put my name on the Crosby, Stills and Nash album and they said they’d get back to me. And they said OK. I had done one demo with Stephen, ’49 Reasons.’ I was managing Heider’s.

“I used Neumann 67 microphones for the vocals on their first album. A 16 track machine. I was obsessed with vocal groups. I also utilized a couple of tune Sony C-37 mikes, which I then didn’t see for years until I was at Neil’s ranch. ‘Yeah I got a couple of those…’ Neil also had some RCA 44 ribbons and 77.

“I was leaving Wally Heider’s and cleaning up and [manager] Eliott Roberts walked in and said, ‘The guys have started their next album without you and really want you to come on up and be the engineer.’ The last day I was at Heider’s was on a Friday, and the following Monday I walked into a studio C Heider’s in San Francisco for the first time. The roadies were there. On ‘Almost Cut My Hair.’ I learned a trick when recording Cream with double stacks of Marshall amps where if I aim the mike right the amp actually acts as a baffle.

“Déjà Vu was a lot harder than the first one. The CS&N they rehearsed for three months and went ahead and recorded it. Three nights into the first album sessions, Ahmet brought Phil Spector by and we played him ‘Suite Judy Blue Eyes’ and ‘You Don’t Have to Cry’ we had done and Ahmet and Phil came by. Got out of the limo, ‘Here’s my new band,’ and they left.

“One of my favorite phone calls, just before Déjà Vu was released was when I was at Heider’s and Henry Mancini called. ‘Hi. Bill Halverson?’ ‘Yes.’ You did the CS&N album. ‘Yes.’ ‘How did you do the vocals?’ ‘I just had them sing around one microphone. It’s them.’ ‘I figured it was that. I just wanted to know.’

“I went to the Greek Theater in L.A. for their debut. Joni Mitchell opening. Neil is now in the band. He added a new dynamic and the stories I’ve heard it was Ahmet Ertegun’s doing.

“A lot of ‘Woodstock’ was already recorded, some of Neil‘s stuff was already recorded when I got there. I did three weeks up in San Francisco and we moved to Hollywood at Heider’s. And then Neil would take the tapes, he didn’t like what we were doing, and he’d go to his house, or to Glendale to Whitney Studios to put that pipe organ on.

“I did some of the overdubs on ‘Helpless.’ We mixed Déjà Vu at Heiders. Neil didn’t like our mixes, ‘cause it was CSN vocals with Neil, and so he’d go mix them on his own, and you’d listen to ‘Helpless’ and ‘Country Girl’ and it sounds like Neil Young with background singers,” revealed Halverson.

“They had a rule with CSN and carried it into CSN&Y, and when I worked with them in 1999 again it was still the rule, whoever writes the song gets final say. And that served them well and I used it with other artists over the years. The art is the writing of the song and then we’re trying to be entertaining with it.

“In the studio I was the only one talking to all four of ‘em. And the job security was great. They were playing me welI and I got a little percentage of it that I gave away in a divorce. I would mix it with one and the other wouldn’t like it. Then fix it.”

A few years ago I talked to photographer Tom O’Neill who took the front cover image of Déjà Vu.

“I spent 1967-1974 doing shooting music subjects. Joni Mitchell, Poco, Crazy Horse, Doors, the Mamas and the Papas, Steppenwolf and B.B. King and the iconic Déjà Vu cover with Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.

“A great photo has to be created from the heart. It has to have that connection. Whether you are photographing a tree or a person you’ve gotta connect with it somehow. It has to have emotion. And if that emotion transfers from what you feel when taking these pictures to the person looking at it, that’s what makes a great photo.

“I try and capture the burst of excitement. I call it the peak of the action and the peak of the moment. It’s that brief millisecond of life where it’s right there. Like a ballet dancer jumping. Or you can also think of it as a big ocean wave. As the wave is building there’s a point where it finishes going to the crest and then it starts its fall of descent. That peak moment of action,” detailed Tom.

“One of the major things that happened to me, through the Monterey International Pop Festival, was connecting with David Crosby. I had gotten special photo passes for Monterey through Derek Taylor, and a mutual friend made sure to get some pictures of David Crosby, who was in the Byrds at the time, I’ll make sure he sees those photos. She knew his business manager, Larry Spector. Larry was involved as business manager with the Byrds around Monterey Pop.

“Around this time I did the CSN&Y Déjà Vu album cover and a front cover picture that is on the cover of Four Way Street. The reason why the photograph is so realistic on the cover of Deja Vu is that they are posing for an authentic Civil War era box camera. It didn’t even have a shutter on it. I literally had to take the lens cap off to make the two minute exposure. I had a tin type inside the camera I had to coat myself before I started. I always say ‘it’s a Matthew Brady type camera.’ I rented the camera from Shaffer’s camera in downtown L.A. on Figueroa Ave. I told them I needed an old box camera that was used in the Civil War. ‘We have one. Give me $150 bucks and you can have it for a few months.’

“I experimented with it. I propped CSN&Y up so they wouldn’t move. They were totally into the shoot. They had gone to Western Costume themselves and each one was in character. It was taken at David Crosby’s house in Novato up in Marin County. I got paid $600.00 and had to pay for the camera. The art director got a check for $1,800.00 and he gave me six hundred dollars.

“I always felt it was Crosby, Stills, Nash and Neil was always outside. He was deliberately not front and center with them by design. I got along well with Neil. Some solo shots and a few pictures on his Journey Through The Past soundtrack album. Neil was always relaxed around me. I went to his house. I went to the ranch. Neil and I sat down in his studio on the ranch that was a giant redwood hand-carved studio, like being inside a cabinet. From the walls to the way it was mounted.

“This is 1969-1973. I loved the fact that he had this stable filled with old cars. That’s what he cared about and I knew about them. He really celebrated the fact where he was. I loved the Scottish Highlander sheep that you would see when you drove in. I think he knew I got him and we shared this get back to the earth mentality. You would go there and Neil would be wearing blue jeans and a funky blue jean jacket. You would return six weeks later and he’d be wearing the same shirt and jacket. That’s him.

“Nash was the person I connected with more than anybody. And yet I feel more connected with David. Graham is a sweetheart. A delightful English man. I knew him the most when he was with Joni. I liked Stephen. He knew what he wanted.”

“A lot of people were disappointed with Déjà vu from their previous studio outing,” offered Dr. Cushing. “Neil really wasn’t really collaborating or recording with the band. Down the hallway from them in different studios or at his home in the Bay area. There was a dark cloud around that album as Graham Nash has discussed.

“And I also thought that Déjà Vu had a little bit of the Beatles White album syndrome in terms of it being much more individual peoples work than a group effort. But the electric set on 4 Way Street are definitely more of a group effort, maybe the most convincing and powerful group effort that they ever did in their lives.

“I loved ‘Helpless.’ I loved how much of a true Neil Young song it was in the middle of the chaos of that group disc. It kind gave the lie to the group, you know, like it was supposed to be a unified group. It wasn’t. This was a Neil Young song on that album the way ‘Julia’ was a John Lennon song.

“He was never a team player and this is another example. From what I understand Neil did his own tracks away from the CS&N, down the hallway or in Northern California. You got the sense Neil was saving the best stuff for a solo album but this one leaked out.”

“He’s always had an agenda,” admitted Graham. “When we were rehearsing the Deja Vu record at Stephen’s house in Laurel Canyon, at the bottom of Laurel Canyon there, he would leave rehearsals and go to the studio and he’d be recording After The Gold Rush. I always allowed people to do what the fuck they want.

“The only time that I ever got really upset with Neil was during the Deja Vu record and Neil would bring tapes in from his studio, we would put voices on, he would take them back to his studio, and he would mix them and it was all a separate thing.

“Neil’s songs on the Déjà Vu record were done by Neil and Neil’s studio when he got our voices and our instruments on at Wally Heider’s in San Francisco.

“At some point that, and a bunch of other things, including too much cocaine, I ended up in the studio, and I said, ‘you know what, we’re fuckin’ blowing this. We are blowing this. We are so good and we have so many great songs and we are fucking blowing this.’

“Stills is in the studio until 6:00 every fuckin’ morning, you know, getting to the studio later and later, I was getting angry about it, don’t forget, I was not with Joan, Stephen was not with Judy, David had lost Christine. I just remember bursting out into tears. Because I felt we were completely blowing something. And the thing that we were blowing had been given to us by the Gods.”

In one of my few conversations with Graham, I had to know how the fuck did he constantly deal with such a non-team player like Neil Young who always had, sometimes in collusion with his manager, an agenda?

“That’s right, and so what? You know, it’s whatever it is. I let people be who the fuck they want to be. And Neil sometimes is a difficult man to deal with. And sometimes he’s a very easy man to deal with. But I respect him completely.

“It doesn’t matter what we’re going through. We all realize that the most important part of our relationship is the music. And it is the music that drowns out all the other things.

“We knew we had the magic. We’ve always known. We’ve always know our music speaks to people’s hearts. We’ve always know it’s been as real as possible. We’ve always know that we’ve taken incredible chances. We’ve always known that we do things that are not normal for a band.

“We’ve always known that we’ve been completely in control. Once you sell millions of pieces of fuckin’ plastic you have control. I say in my autobiography that in the early days of recording with the Hollies we weren’t allowed to even touch the board. If I wanted more bass I’d have to ask Ron Richards (producer) who then would have to ask Peter Bown (engineer) to bring up the bass. After we’d had hit records that all changed. Because they began to realize that these guys who were not wearing white lab coats really knew what they were doing.

“And we never lost the ability to do what we do. We always wanted to be winners and not victims. If you don’t have the ability to call up a studio and say, ‘I’m coming in next Thursday through next Thursday and this is the band,’ and getting all the tape and engineers together, and if you lose that ability, that is a dreadful thing. And we have never lost that ability.

“I mean, a great example is my song ‘Teach Your Children’ going up in the top twenty and Ahmet Ertegun telling me I was ‘going to have a number one hit.’ Then there’s the killing of four students (shot by National Guardsman) at Kent State (in Ohio). And we do Neil’s song ‘Ohio.’ And we think America killing its children is more important than us having another hit record. And so I told Ahmet to pull ‘Teach Your Children,’ and put ‘Ohio’ out. We decided on ‘Find the Cost of Freedom’ as the B-Side.”

Young’s song “Ohio,” in mid-May 1970, was a response to the four students shot and killed by the National Guard on the campus of Kent State University in Ohio.

In a September 1973 interview with B. Mitchell Reed broadcast on KMET-FM (94.7) in the Los Angeles market, Young discussed “Ohio.”

“At the first part in my career, or whatever, I wasn’t into politics, you know. And then all of a sudden I sort of got into it. Because of what was going on around me I couldn’t ignore it, you know. It was too obvious…I didn’t feel I would be typecasting myself as a political person. Writing that song was just a pure reaction to the cover of TIME Magazine. I never really thought about it any other way.”

Bill Halverson engineered that epochal session.

“I was working with Stephen Stills at the Record Plant in L.A. and got a call from a roadie. ‘We’re gonna bring all the gear over tonight.’ Studio A had an Ampex tape recorder. I hated their tape machine and made them rent a 3M 24 track from Heider.

“I got some more mikes from Heider ‘cause the whole band was coming. John Barbata showed up and I got a drum sound. Plugged Greg Reeves’ bass and set up the amps. Miked them 57 vocal mikes and know that they are gonna create the sounds they want and I just need to get it on tape. Heider’s studio had leakage with the guitar amps so I set up some additional Dynamic mikes.

“They show up. We rehearsed the song, maybe 16 bars and they stopped. A couple of takes and we had it. There again, no overdubs, all live vocals, even the ad libs of Crosby on the end. I had blinders on working and had no idea that the whole Kent State thing had happened. I get credit for being the engineer but it was all five of us hovering.

“We were listening to the mix, it was gonna be a single, and they needed a B-side. We’d been rehearsing ‘Find the Cost of Freedom” to do an encore at CSN&Y concerts. I set up four chairs, and put them knee-to-knee like they were at a card table. With one microphone for Stephen to play guitar and sing and they went out and we sort of got a blend thing going. I put them on five tracks. As soon as it ended, I backed it up and got it onto five more tracks. When Stephen heard a part he knew what he’d do next. They sang their parts a second time and we mixed it. Done.”

“Neil’s protest number ‘Ohio,’ with CSNY, was just phenomenal,” marveled Clem Burke of Blondie. “A great lead guitar riff by Stephen Stills, which, besides the political statement it was making, just sucks you right in.”

“The impact of “Ohio” reached over to England where Mott the Hoople recorded a live version of it one night in 1971 when they were supporting Free at the Fairfield Hall in Croydon, south London.

“In his twenties Mick Ralphs had a voice uncannily similar to Neil Young’s,” Ian Hunter emailed me in 2015. “We were doing an album called Wildlife and Mick had a lot to do with that album—a tad of country common sense in among our usual sea of chaos. Mick came in with it—sang it—and that’s the one you’re hearing.”

In summer 1970, the late esteemed Canadian music journalist, author, and broadcaster Ritchie Yorke conducted an exclusive interview with CSN&Y for his Rap with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young college radio special program that was distributed as a promotional tool by Atlantic Records. Yorke taped the outfit at Peter Tork’s house, which they were renting for rehearsals.

An excerpt was utilized with his permission in my 2015 book Neil Young Heart of Gold.

“Neil Young: Right from the beginning, he [Graham Nash] and I hit it off. Now I’m finding a bunch of new friends and it’s groovy. Willie [Graham Nash] knows how to make you feel at home. He’s groovy and very honest.”

“Stephen Stills: Neil is just about my best friend in the entire world, really. We’re both people that grew up where our whole clan was kind of different from everybody else around us. There always was a certain sense of alienation from people around us. They’re all old things and no amount of analyzing and psychotherapy can ever wash away some of those scars. You have to do it yourself. And we both kind of uniquely know that about one another and it’s nice. We can look each other in the eye. We blew it before when we didn’t. And we’re trying harder now.”

In Young’s 1973 radio interview with B. Mitchel Reed, Neil commented about joining CSN&Y.

“I think it started with Stephen and Ahmet. Crosby, Stills and Nash had finished their album and thinkin’ about going out on the road to promote the album. When they started thinking about it, they realized, to have me there would be another addition, just another step. And they wanted to do that to carry that Springfield thing that Stephen and I had going all the way into their thing, you know, with those vocal sounds. I guess that’s why they asked me to join.

“At that time I was really excited, you know. Because I hadn’t been doin’ really well. I had a couple of records out, neither one was really too successful. And then I joined Crosby, Stills and Nash and did that tour with them and my records started takin’ off. And so I guess it helped me on all levels, joining them. Besides making what I thought was really great music that was really getting me off. I mean more people were getting to know me as an artist and to get interested in what I was doing. So it was a really good thing for me. It was a good thing for everybody I think ‘cause I think I added a lot to them, too in helping them.”

“I got to know Neil a little bit during 4 Way Street. I recorded all of it,” volunteered engineer Halverson. “We did a week at the Fillmore East. The first night at the Fillmore it wasn’t gonna happen ‘cause they’re fighting in the dressing room. We had done the sound check and had it all going right.

“The story I got was that Bill Graham said, ‘Dylan and the Band are in the audience.’ He said something to them to come down and get them to play. Heider’s truck was with ABC-TV in Nashville doing The Johnny Cash Show.

“When the show was over Heider sold the truck to the Record Plant in New York. I had done so much remote recording at Fillmore West and Winterland in San Francisco. We did Fillmore and then two nights in Chicago. Then we did the Forum in Inglewood.

“When you are doing live harmonies and lookin’ at each other on stage, you’re not on microphone and all of a sudden the vocals go away. It took ‘em a while to stay on mike when they were lookin’ around. Playing live Neil is wonderful. He makes Stephen better and Stephen makes Neil better. Crosby is probably one of the best rhythm guitar players I’ve ever recorded. Crosby is real underrated in all that. He’s just anchoring it with the bass and drums,” underscored Halverson.

“CSN&Y’s 4 Way Street LP double LP was released in 1971, culled from tour dates in 1970,” reiterates Dr. Cushing. “It remains one of my favorite albums. It’s looser and more intimate and more spontaneous and more risk-taking and more of that combination of heavenly folk music on the acoustic side and of sublime Buffalo Springfield meets Crazy Horse rock on the second half.

“I think they do everything on that album that they do well at its very best. I think the two long jams, ‘Southern Man’ and ‘Carry On,’ great guitars and excellent drumming and bass playing, ‘Ohio’ is fabulous. ‘Triad,’ and ‘The Lee Shore,’ the song selections and the way the four personalities are balanced. Everything was done correctly including the decision to have the album begin with the fading up of the last few seconds of ‘Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.’ So they kind of get it out of the way by making a joke out of its popularity.”

Graham Nash was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) by Queen Elizabeth in recognition for his contributions as a musician and philanthropist.

On April 27, 1966, after a Hollies’ press party event was held at Imperial Records in Hollywood, GO! Magazine weekly music columnist Rodney Bingenheimer invited Nash to attend a nearby Mamas and Papas recording session of “Dancing Bear” at Western Recorders on Sunset Boulevard.

Graham then met and talked at length with group member Cass Elliot.

“I only went with Rodney to see Michelle (Phillips). But Michelle, Denny (Doherty) and John (Phillips) were doing an overdub in the studio, and Cass was outside the studio. I started talking to Cass

“You know the truth is there’s a part of me that really believes none of this would have happened without Rodney. Incredible music has been made from that moment.”

During the afternoon of April 28, 1966, matchmaker Cass picked up Graham at the Knickerbocker Hotel and introduced him to David Crosby at her house in Laurel Canyon. Crosby subsequently connected Nash to Stephen Stills, and Crosby, Stills and Nash was formed.

“We were staying in Hollywood at the Knickerbocker and she picked me up around noon in her convertible Porsche. I said, ‘where we going?’ ‘We’ll be there in five minutes. Don’t worry.’ And drove me up to Laurel Canyon and I met Crosby. And once again, my life has never been the same…

“It not lost on me that you can be in the Laurel Canyon from Hollywood in 5 minutes. Not like in England where it’s 90 minutes that’s to get to the nearest bus stop. So I was in heaven. I was free. My first wife and I were getting divorced. I had already separated from Rose. I was a free man. And I must tell you that I took to the Laurel Canyon scene like a duck to water. It was just amazing to me that these people would be living in this kind of very rural area.

“I just felt so free. And more importantly, I felt appreciated. And that goes a long way with me. If you know what it is I can do and you appreciate that, I feel a lot better about things. And it seemed to be the Hollies’ reputation in the Laurel Canyon scene was a big one.

“I felt fantastic. I know that because of the British invasion and what British music was doing to the American scene, and how admired British groups were by American groups, I felt pretty confident in myself. You know, I happen to believe, and this is not ego talking, I’m pretty good at what I do.”

I wanted to know what it’s like for Graham to revisit and still sing his songs and CSN&Y selections from 1969-1971 and why are they are still relevant today?

“It’s the same thing, kid. If I can sing you a song with my guitar and piano and knock you on your ass it’s a great song,” summarized Graham. “And it doesn’t matter how many people you are playing it for. The essence of the song and what the song says still lives to this day.”

On the CSN&Y 1974 tour, their subsequent reunions, and recent Nash solo outings, always included in set lists are political-themed songs: “Chicago-We Can Change the World,” “Ohio,” “Military Madness,” and “Long Time Gone,” along with many new tunes. Do the older songs somehow resonate even deeper because more history is attached to them?

“That’s because the history has never changed. You could take the word Vietnam War and replace it with Afghanistan and IRAQ. You can take a song like ‘Great Concern,’ that I wrote about Washington during the Watergate hearings. It’s the same thing going on now. History has not changed. We have refused to learn. Humanity still doesn’t learn…”

Graham Nash, born in the sea coast town of Blackpool in 1942, grew up on the bombed-out streets of Salford, and raised near Manchester where the Hollies were formed, experienced as a tyke the atrocities of war when the Germans reduced his neighborhood to rubble.

I told Nash’s that some of his tunes like “Military Madness” were supposed to help end wars or at the very least educate people about the machinations of the military. I reminded him that war is still happening globally.

“I know. It’s very depressing. What’s going on is what was always going on. This world is controlled by the media and the businessmen that make profit from war. It’s the same fuckin’ story. It’s awful and it’s criminal.”

"It was in September, 1969, when Ronnie Rossman, a high school friend, first played me the debut album of a group called Crosby, Stills and Nash, recollected filmmaker David Leaf, and author, known for his definitive biographies of the Bee Gees and Brian Wilson and wrote the Beatles and Beach Boys chapters for Capitol Records 50th Anniversary book.

“I had never even heard of them, didn’t know anything about where they had come from, but I quickly (like less than halfway through the first listen to ‘Suite: Judy Blues’) came to worship them for their harmonies and by album’s end, the songwriting, their message and their immense and diverse talent. Unbeknownst to us, the Beatles journey (with the release of Abbey Road was coming to an end, but it was instantly clear to me that CSN had the artistic potential and original voice/voices to be the American Beatles. Or at least for me.

“Ted Krever, another friend in my college dorm (he’d gone to Woodstock specifically to see them, and it’s actually his voice on the Woodstock soundtrack/film going ‘Yeah,’ after the announcer introduces CSN&Y) explained the origin story of the group. I already liked the Byrds and the Hollies and he turned me on to the Buffalo Springfield (I was supposed to see them in November ’67 as an opening act for the Beach Boys, but the night before the show, Bruce Palmer was deported.) I became a really big Buffalo Springfield fan. We spent hours, days, weeks, months, years in the dorm, along with my roommate, David Poleno, singing along to those records. We learned every word, every note, every harmony. For that first album, for 1970’s Deja-Vu, for 4 Way Street, et al.

“In the 50+ years since I first became a fan(atic), I’ve seen them in just about every combination except the Stills/Young Band. CSNY headlining a stadium show with Joni Mitchell and the Beach Boys. Stills solo (3 ½ amazing hours at Madison Square Garden two nights before the Bangla Desh concerts) and with Manassas. Crosby-Nash. Neil solo, acoustic and electric. Nash solo. Crosby solo. CSN reunion tours.

“One of my biggest musical regrets is a CSN show I had tickets for (6th row orchestra!) to see them at D.A.R. Constitution Hall in October 1969 was “postponed” because Croz’s girlfriend (Christine Hinton) had been killed in a car crash. I even saw Crazy Horse when they played my college auditorium without Neil.

“I’ve had the privilege of working a little with all of them. And, obviously, their musical legacy is secure. They mattered then. They changed the landscape. Their music endures and still can delight us with its melodic/harmonic magic and lyrical meaning.

“I’m confident that if they could have stayed together for ten years and made a dozen albums that cherry-picked the best of their solo songs from the 1970s, I think they would musically have been to that decade what the Beatles were to the ‘60s. It really doesn’t get any better,” underlined Leaf who, having made award-winning documentaries on the Bee Gees, Brian Wilson, John Lennon and James Brown, is currently finishing a film on Dion (Born To Cry).

Since 2010, Leaf has been a professor at the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music where he teaches courses in popular songwriting, rock documentary and the Beatles.

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and brother Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For 2021 they are writing and assembling a multi-narrative book on Jimi Hendrix for the same publisher.

Otherworld Cottage Industries had just published Harvey Kubernik’s 500-page book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring Kubernik interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Henry Diltz, Graham Nash, Chris Hillman, Roger McGuinn, Mary Wilson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, John Ridley, Curtis Hanson, Dick Clark, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Harvey served as Consulting Producer on the 2010 singer-songwriter documentary, Troubadours directed by Morgan Neville. The film screened at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival in the documentary category. PBS-TV broadcast the movie in their American Masters series.

Kubernik appeared in director Matthew O’Casey’s 2012 Queen at 40 documentary broadcast on BBC Television, (released as a DVD Queen: Days Of Our Lives in 2014 via Eagle Rock Entertainment).

Harvey Kubernik, Henry Diltz and Gary Strobl collaborated with ABC-TV in 2013 for their Emmy-winning one hour Eye on L.A. Legends of Laurel Canyon hosted by Tina Malave.

Harvey Kubernik was also spotlighted for the 2013 BBC-TV documentary Bobby Womack Across 110th Street, directed by James Meycock. Womack, Ronnie Wood of the Rolling Stones, Damon Albarn of Blur, the Gorillaz, and actor Antonio Vargas participated.

In 2014, filmmaker Matt O’Casey recorded Kubernik in his BBCTV documentary on singer Meat Loaf, titled Meat Loaf; In and Out of Hell, broadcast in the US market in 2016 on the Showtime Cable TV channel.

In 2019, Harvey was featured on director Matt O’Casey’s BBC4- TV digital arts channel Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird. The cast includes Christine McVie, Stan Webb of Chicken Shack, Mick Fleetwood, Stevie Nicks, John McVie, Christine’s family members, Heart’s Nancy Wilson, Mike Campbell, Neil Finn, and producer Richard Dashut.

In 2020 Harvey served as Consultant on Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time documentary directed by Alison Ellwood which debuted om May 2020 on the EPIX/MGM television channel.

UK-based Palazzo Editions arranged Harvey’s music and recording study, an illustrated history book, Neil Young, Heart of Gold published in 2015, by Hal Leonard (US), Omnibus Press (UK), Monte Publishing (Canada), and Hardie Grant (Australia), coinciding with Young’s 70th birthday. A German edition was published in 2016.

Kubernik has penned a back cover book jacket endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada, will be publishing this fall 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years).