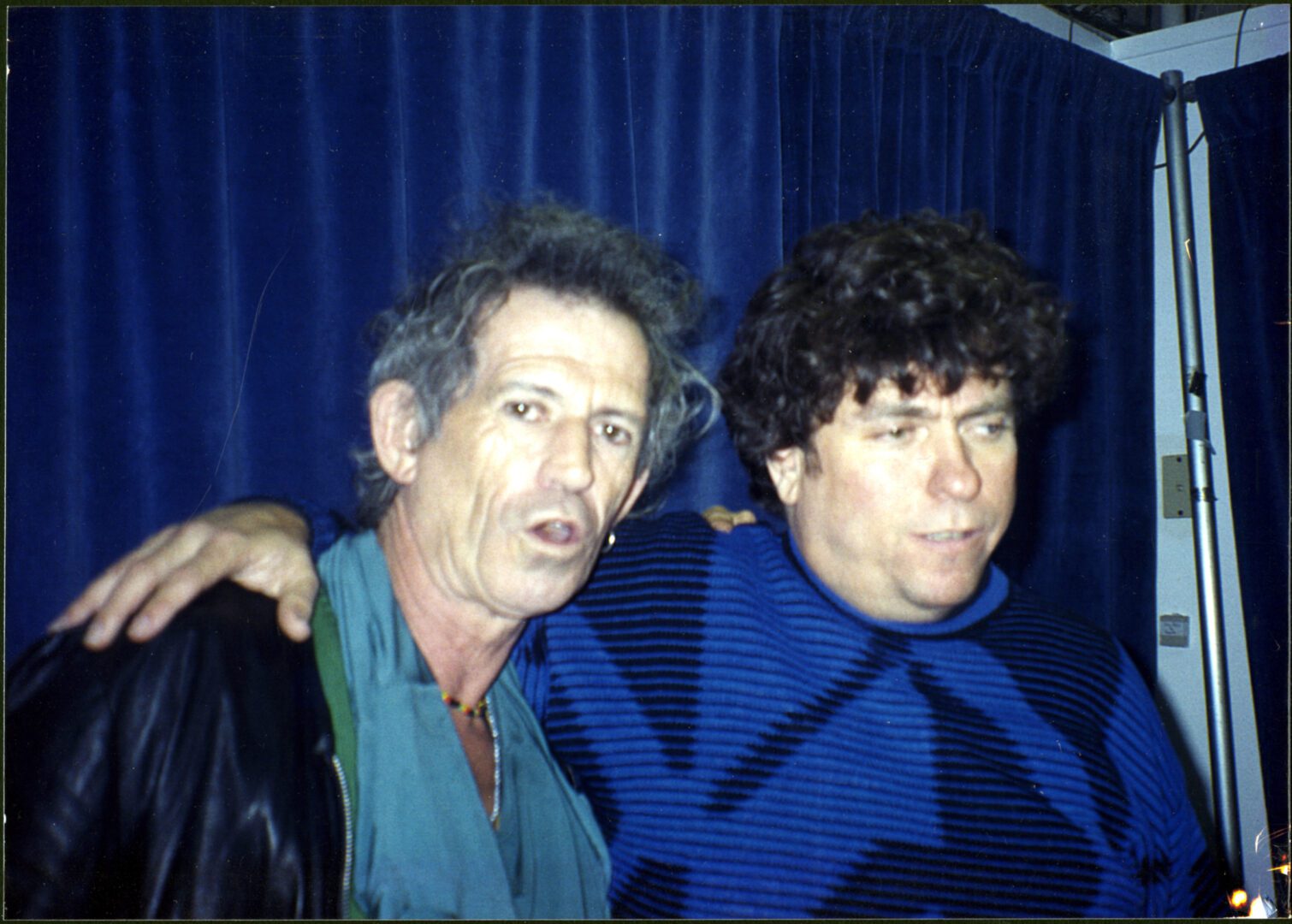

To celebrate Stones guitarist Keith Richards' birthday, we're looking back on a 1997 interview...

Sunset Blvd. has geo piety for The Rolling Stones. Much of their durable and exciting music has been recorded on this street with record producer Andrew Loog Oldham at RCA Studios and Jimmy Miller in Sunset Sound, and recently at Ocean Way studios with Don Was where Voodoo Lounge and Bridges To Babylon were cut.

In 1997, during a session one evening at Ocean Way, songwriter Keith Richards, the Stones’ guitarist/singer/band leader explained a new recording project he had just done with engineer Rob Fraboni in Jamaica.

Wingless Angels, a collection of five Nyabinghi Rastafarian drummers and Sister Maureen in drum, chant and vocal forum.

Richards also serves as executive producer on the Wingless Angels just out offering, and it appears on his own Mindless Records/Island label. “I’ll talk to you ‘bout it when we (Stones) tour,” he promised.

Arrangements were made for a formal taped interview with Keith backstage before their San Diego concert at Jack Murphy Field/Qualcomm Stadium.

Q: When I last saw you during The Rolling Stones’ recording sessions at Ocean Way in Hollywood, you mentioned you were co-producing with engineer Rob Fraboni a collection of five Nyabinghi Rastafarian drummers and Sister Maureen drum and chant sessions. Now, Wingless Angels which you served as executive producer for your own Mindless Records/IslandRecords label has just been released.

A: They sing like angels, but they can’t fly. I’m referred to as Brother Keith. The label emerged out of the recording. This started after the ‘Voodoo Lounge’ tour. Recorded in my front room. It’s evolved over the years, and each time I visited Jamaica I would drum and chant with the Rasta bred’ren. The recording was done on HDCD, with like four microphones, and you can hear frogs, crickets around the weed. (laughs). Actually, the Wingless Angels come from Steertown, and you might know the work of one of the members, ska legend Justin Hinds, years ago had the Dominoes’ “Carry Go, Bring Home.” A vocal harmony group. The drums are kept at my house (in Ocho Rios) in the hills of Jamaica. These are ‘healing meditations.’ They’ve been friends and family for over 25 years. They like to play, and are full of life and energy.

Q: I know a little bit about the Nyabinghi sect to which the Angels follow and the Biblical dietary laws, and the one-drop drumbeat. Then there were the supplemental sessions you produced in New York with fiddle player Frankie Gavin, and bass added to the mix, as well as your own subtle guitar parts. Run down the healing and the soundwaves.

A: The healing aspects, in a way there seems to be, yea. I mean, I was always aware of it because I played with those guys for many years. That’s what I do in Jamaica, apart from a few other things. (laughs). And, we gather around and play. And, it always has that effect on . . . They’ll be the first ones to say why we do it. Because it heals us after the day, you know, the struggles of the day. In a way, I think it has something to do with the actual beat they play which is slightly under heart rate and it works on the human metabolism, even if you’re not particularly listening to it or into it. If you’re within an earshot of it, it will affect you. It’s soothing. It calms people down. It’s good for the soul.

Q: Do you get a more natural drum sound. Like can I hear it on the song ‘You Don’t Have To Mean It’ from Bridges To Babylon?

A: There’s no doubt, that while recording the Angels that a drum is a cylinder with two skins on either side, and that’s what really gives it a special sound. And I never realized that we were cutting like drummers, especially Charlie off from a whole half a drum. (laughs).

The melodies, the sounds, the Wesleyan hymns are from the British church and Scotland, then over to Africa. In a way this whole ‘Angels’ thing is pretty left wing. I didn’t even intend to make the record. I got to Jamaica after the Voodoo Lounge tour just to kick back and write.

And, some people came by from The Jamaican Film Board and we were talking that night and they said, “You should record this.” And in typical Jamaican fashion, with nobody saying anything, suddenly this truck arrives in my driveway. A recording truck from The Jamaican Film Board. (grins). And I thought, “I’ve got the equipment. I’ve got the band. But, who’s gonna punch the buttons?” These guys don’t record just like that. Studios don’t agree with ‘em because they’re split up and you can’t get the feel. Years ago, we had a false start at a recording studio in Kingston, but tiny cubicles spread out . . .

Then there’s a knock on the door the next day, and Rob Fraboni turns up. He had just arrived in Jamaica to celebrate his wedding anniversary and I said, “Come here, you’re working.” (laughs). And then once we finished recording in Jamaica, I took it back to New York. I said “I’m gonna try a few things on this. Experiment a little bit.” I think when we were recording, I heard other sounds. I’ll play ‘round with it. I get to New York, there’s a knock on the door, and it’s Frankie Gavin, who’s the only guy. “I’m in town for two or three weeks. Got anything happening? Got any work?” So, in a way, everything was thrown at me. I didn’t plan this. Things started penetrating. I didn’t intend to do it. But somehow it was occurring. So, maybe JA wonderful. Then Chris Blackwell came around one evening and heard what we had done, and said, “When you finish this, I’d like to put it out.”

Q: How did the “Wingless Angels” recording impact your recording activities as well as your work in the studio with The Stones?

A: With the Angels, I got very interested in ambient recording. The room is good if you know what you’re doing. Use as few microphones as possible. All the tinkering, splitting things up can never achieve. The whole idea when you play music is to fill the room with sound. You don’t have to pick up each individual instrument, particularly in order to do that. Because a band is several people playing something. And somewhere in the air of the room, that sound has to gather in one spot. And you have to find that spot. (smiles).

Q: Are there advantages in knowing musicians who you know for 25 years and then record with them?

A: Yes. I’ve known them for a long time. That’s the main answer. It was only years later that I was really filled in on the fact that they’ve never ever accepted anybody to play with them before. Black or white, or with an instrument. They were purely voice and drums. Over the years they invited me, and I don’t know why.

Q: They didn’t know who I was when I first met them, if that means anything. The Rolling Stones meant nothing to them. They’re fisherman divers who live in corrugated land shacks and the Rolling Stones are not the first things on their menu, ya know.

A: Do you like to write and record in Jamaica. I know the Stones’ Goat’s Head Soup was recorded in 1973 there. I totally dig the guitar in “Heartbreaker” by the way, even though it’s out of tune with the electric piano. Maybe that’s the idea

Q: (laughs). Yea. It’s very easy to write in Jamaica. I don’t find it difficult to write anywhere. But in Jamaica, it’s particularly easy because they are so musically oriented, the Jamaicans. I mean to be quite honest with you the Jamaicans do nothing without music. Which for a musician is fantastic! Because, even if you’re not playing music in your own house, you can hear half the town below in little villages and there’s music playing. They do everything to music. It’s an open environment when we record. You can hear the rain on the recording.

Q: A lot of trust in the scene?

A: Exactly.

Q: What did you gain from the initial recording of the “Angels” CD?

A: When you’re recording something as seemingly simple of just drums and voices, for the first few days, microphone placement is very important. We’re trying different angles. You never point the microphone actually at the instrument. You’ve got them in the corners pointing and once you’ve found those placements, you don’t really change them. One of the joys of it was that you’re not really aware that you’re actually making a record. Yes, you are recording but at the time I was recording it I had no particular outlet for it. I mean as I mentioned, Chris Blackwell came by that evening, “if you finish this, I’d love to put it out. You know, the whole thing was sort of handed to me mysteriously from above, ya know.

Q: For years I’ve been aware of Rob Fraboni’s engineering and producing. I know he did a little bit of work on Goat’s Head Soup in Los Angeles at Village Recorders. He also engineered Bob Dylan’s Planet Waves, and engineered and produced a lot of reggae. Rob did a lot of engineering and mixing as well on “Bridges To Babylon.” What did attract you to his board work?

A: He knows an awful lot, man, about recording. He knows a lot about microphones and I’ve worked with him off and on for 25 years. Many years we didn’t work together. Rob Fraboni is the only engineer I know, apart from, or maybe even Jamaican ones that knows these guys (Wingless Angels) for 15 odd years, ya know. The only guy who the Angels know so there’s no like strangers in the room to inhibit the process. It has to have that feel. That’s why we left on all the talk and some of the laughs.

Q: Have you, obviously of all people, noticed that time stands still when Wingless Angels is being played. Maybe it’s the Jamaican location of recording.

A: I think because it’s timeless music. I mean, I’ve had African guys say, “This is more African than what is going on in Africa.” I call it ‘marrow music.’ Not even bone music. It strikes to the marrow. It’s like a faint echo . . . The body responds to it and I don’t know why.

You asked me earlier about Goat’s Head Soup. I was only really learning about Jamaica then and when you’re making records, you’re pretty much myopic. And it was only really after recording ‘Goat’s Head Soup’ and staying in Jamaica for several months, which was when I bumped into the Angels on the beach. And we got talking and playing. But in certain ways, Jamaica doesn’t change that much. There’s a very solid rhythm to life there, which they seem to be able to adapt to even incoming technologies that speed the rest of the world up. What I really love I think about Jamaica is that they have a rhythm all their own and everybody, including yourself after a few days you can’t get out of step, man, you know.

Q: I know Sister Maureen co-wrote many of the chants and I guess joined, or was asked to join Wingless Angels during a gig at a Steertown bar one night. I recall meeting Inner Circle, Jacob Miller, interviewing the Wailers, and I always noticed there were never any girls around in the studio. First you get on the team, then Sister Maureen. It’s a heavy trip for a woman to be included. Right?

A: Well, when I first met Wingless Angels, they wouldn’t let women in the room while they were playing, let alone play with ‘em. That’s one of the changes which is good.

Q: What did she bring into the recording?

A: She brought women into it. She stopped segregation. (Bongo) Locksley is the main man and he said, “You gotta hear what we’re doing.” O.K. “Sure, I’ll pop up.” Then he said, “we’ve got this chick in,” and he started explaining it to me. (laughs). “You guys?” You know, a woman in the band! Times change, you know what I mean. And she brought a lot of strength. A lot of new influences. And she brought the woman’s touch in. That soft touch.

Q: What’s it like, the mix, the recording? I noticed during The Stones’ recording sessions it’s very collaborative, lots of involvement in detail.

A: With the Angels it’s kinda like miking it. Once you’ve got the basics set up, the first two or three mixes are difficult because you’re still searching and then suddenly, it clicks, “we’ll put the drum there,” and then “we’ll hold that.” After that you can almost go through the rest of them and keep those same settings because the music itself is not going to change.

Q: What’s the best way or atmosphere to hear Wingless Angels?

A: Flat on your back, with some partners, rum and weed. (laughs).

Q: Let’s talk about the Rolling Stones. I’ve seen both outdoor and indoor shows and the sound fills the stadium. I have a blast at the gigs. How has the tour been going?

A: Fantastic, man. The stadium parts have been great. I’ve never known a tour to go . . . You kind of accept usually when you start a tour for it to have its high points and low points and you start to go for a happy medium, and hope there’s more high points than low. But this one is not like this. Very strange, but since Chicago, day one, the band and the sound, and the whole feel of it has gone on a steady upward plane. The graph looks amazing. As far as the band’s feeling good, I think it’s got a lot to do with the new sound system, and with Robbie McGrath, the mixer, has really got our live thing down. I mean we’ve got the guitars where we want them. But I think it’s a mixture of that and also the experience of the band.

Q: Did the Wingless Angels” experience have an impact on the way you play with your band now on this tour? You know what I’m trying to say. I think and hear it in the live show more holes, a little bit.

A: I’m playing a little different on this (new) tour. Yea. I’m more conscious of dynamics. It’s exactly what it’s about. To make a record like the Wingless Angels, ‘Oh this is a great little pastime . . . a hobby’ when you’re doing it. You are not thinking in terms of that. But when you’ve finished it you realized that you’ve learned a whole lot about recording and music from like ten guys or so who live up in the hills in Jamaica and they’ve taught me, or re-taught me, or reminded me of like the spaces that can be left and that silence is your canvas and never forget it.

Q: And what about playing on the second stage? A smaller place right in the middle of the stadium for a set of tunes that I know really involves the audience. Not that they haven’t gotten their ass kicked from the gigantic full stage show they’ve also seen.

A: It’s beautiful, great. It’s another thing. Once you’re on the stage it’s just some floor boards in spite of it. And you’re not really aware of everything you are seeing. But what really keeps tours going and alive for the band and therefore for the audience I think is to change it and to play the smaller joints indoors. And the small stage with the show. It’s necessary to change the scale sometimes.

Otherwise, you can really get used to the large thing. And you realize when you’re playing a small gig that you get dynamics back and you can re-translate that back to the big stage.

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015's Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016's Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017's 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll TV Scenes) is scheduled for early 2026 publication from BearManor Media.

Harvey spoke at the special hearings in 2006 initiated by the Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation.

In 2017, he appeared at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in its heralded Distinguished Speakers Series and also a panelist discussing the forty-fifth anniversary of The Last Waltz at the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles in 2023).